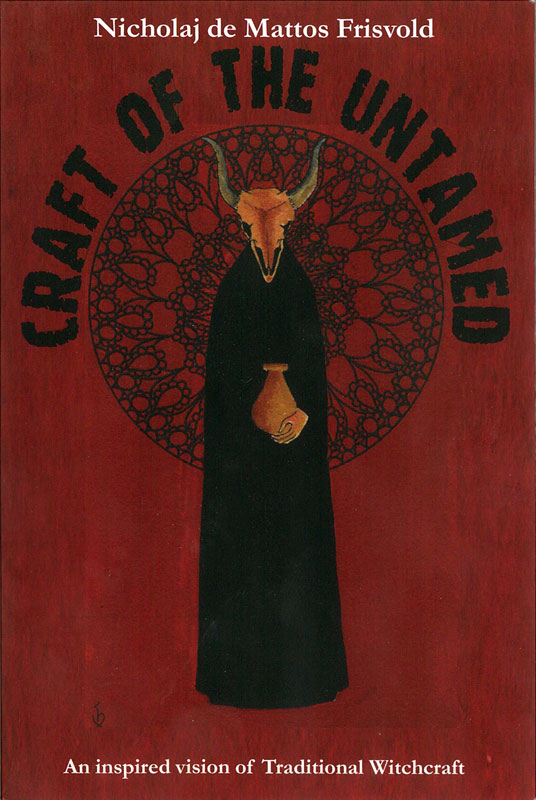

There is no shortage of books about Traditional Witchcraft upon the shelves in the Scriptus Recensera library, filled as it is with worthy contributions from Michael Howard, Gemma Gary, Shani Oates, Andrew Chumbley, Nigel Jackson and others. And that’s not to mention the works of the pretenders and imitators that haven’t been granted access to these hallowed halls. The question that arises, then, is whether Nicholaj de Mattos Frisvold is able to bring anything new to the table. Frisvold certainly seems to think so, cutting my musings off at the pass and making his case early on for one major point of difference: a focus not just on the British and Scandinavian sources for witches, but on the parallels that are to be found in Italy and even further afield in South American expressions of magic, especially those connected with African diasporic religions. Thus, a consideration of the crossroad in witchcraft inevitably makes a brief detour into the comparable symbolism in Yoruba belief and Vodou, facilitating a full circle of motifs when ‘the kingdom’ from the Cult of Exu finds an analogue in the Witches’ Sabbath.

There is no shortage of books about Traditional Witchcraft upon the shelves in the Scriptus Recensera library, filled as it is with worthy contributions from Michael Howard, Gemma Gary, Shani Oates, Andrew Chumbley, Nigel Jackson and others. And that’s not to mention the works of the pretenders and imitators that haven’t been granted access to these hallowed halls. The question that arises, then, is whether Nicholaj de Mattos Frisvold is able to bring anything new to the table. Frisvold certainly seems to think so, cutting my musings off at the pass and making his case early on for one major point of difference: a focus not just on the British and Scandinavian sources for witches, but on the parallels that are to be found in Italy and even further afield in South American expressions of magic, especially those connected with African diasporic religions. Thus, a consideration of the crossroad in witchcraft inevitably makes a brief detour into the comparable symbolism in Yoruba belief and Vodou, facilitating a full circle of motifs when ‘the kingdom’ from the Cult of Exu finds an analogue in the Witches’ Sabbath.

Frisvold makes another distinction at the outset, noting that similar books are often highly eclectic in their approach, uncritically embracing myths and legends, with an attendant use of etymology and epistemology. However, there is often little to differentiate what is presented in this book with the style of, say, Michael Howard, Nigel Jackson and Shani Oates, three authors who, to my mind, have often written with an encyclopaedic, info-dump approach that embraces folklore, legend, myth and etymology in a rather broad manner. Frisvold’s sources are a little different from those of Howard, Jackson and Oates, though there are certainly some common ones; and titles from Cappall Bann do make a significant contribution to the bibliography. Instead, Frisvold draws heavily on material from Hermeticism and the Western Tradition, with an obvious and fairly frequently fondled touchstone being found in Cornelius Agrippa.

There is a utilitarian approach to the writing here with a conversational tone that precludes much in the way of scene setting or background exposition when information is presented. Frisvold obviously knows his stuff (except perhaps for the bit about Robert Johnson dying at the crossroads, wahhh?), so there’s no feeling of him skimping on the details out of ignorance, and while you don’t need to over explain things to an occult audience (where a certain familiarity with the material is expected), it still feels like more context could be provided before the nuggets of knowledge are dropped. The brevity of Frisvold’s writing is also evident in a lack of transitional phrases tying paragraphs together, with ideas often being abruptly introduced as if they have no immediate relation, to the subjects that have gone before. This leads to a jarring effect when blocks of information appear, if only briefly, as if they are non sequiturs, barren of any relation to the wider discussion.

This slight lack of focus bleeds into the chapters, which, although given clear titles and themes, don’t necessarily reflect an obvious flow throughout the book; suggesting, although I have no evidence to corroborate it, that they started as individual essays. These chapters cover off various areas of witchcraft, with the first one being the aforementioned consideration of the symbolism of the crossroads. Chapter two, Solomonic Magic, is a wide-ranging slightly unfocused discussion that covers more than what its title would suggest, lurching from grimoire magic, to folk concepts of the Devil, to liminal Roman and Etruscan deities and ultimately to inverted crosses. The focus is tightened a little more in a discussion of blood and ancestry in systems of witchcraft and, inevitably, beyond. Arguably the most successful chapter is one in which the gaze lingers on a central theme for longer with a consideration of the Witches’ Sabbath and the traditions surrounding the Mount of Venus. I am rather partial to the emphasis Frisvold gives to Hela, focusing on Her role as an initiatory goddess of witchcraft and the underworld, addressing Her as “Ninefold Mother, Hel, Herodias, Holda. Queen of Elphame, Queen of Venus’ mount.”

Many of the chapters conclude with a practical activity that put into action what has just been discussed. Thus, a chapter that could be broadly said to be concerned with sympathetic magick concludes with a series of brief malefic spells, such as a poppet charm for harm and healing, and a procedure for creating a mojo bag for protection. In the chapter on the Witches’ Sabbath, instructions are given for a rite of transvection using flying ointments, while the consideration of blood ties is concluded with a procedure for feeding the ancestors

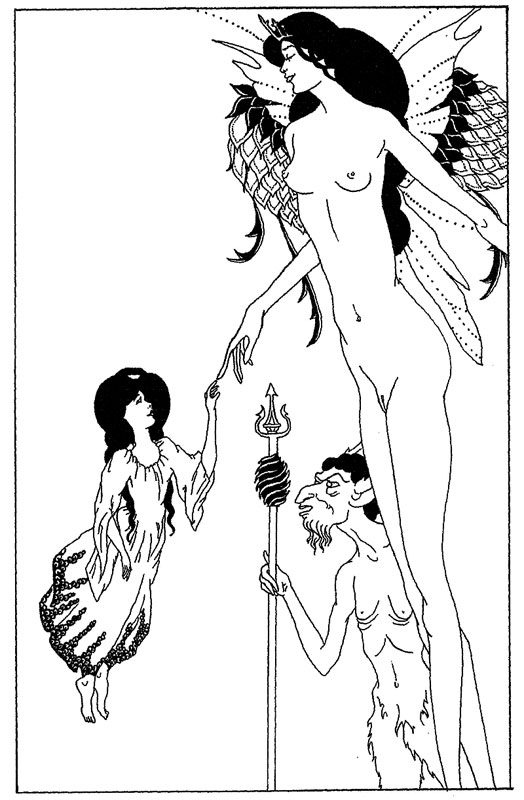

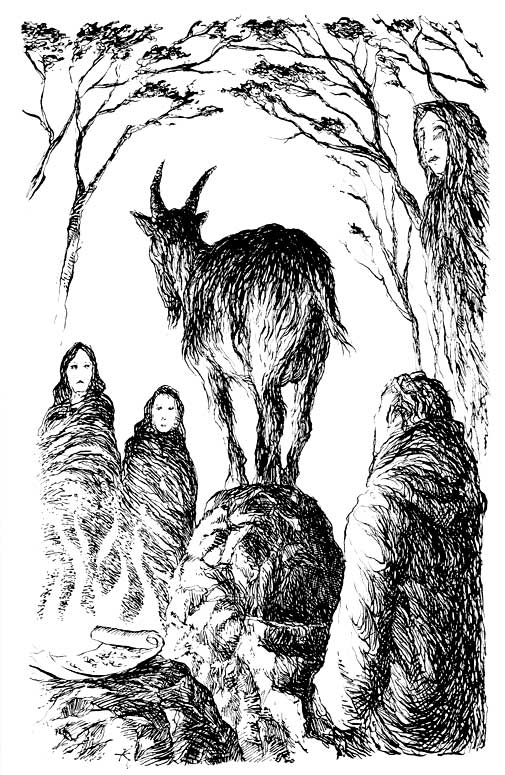

Each chapter in Craft of the Untamed is prefaced with a black and white illustration by Audrey Melo, who also provides the painting that features on the cover. The reproduction of these internal illustration varies widely in quality, with everything from acceptable to quite pixelated, to goodness me, they’ve put pixels in their pixels so they can pixel when they pixel. These images are also wildly inconsistent in style, with Melo having no discernible look of her own and instead riffing on the aesthetics of various familiar esoteric artists. There’s a few atavistic Austin Osman Spare motifs, a fairly convincing Aubrey Beardsley pastiche, and a couple of images that are an obvious tribute to the unknown artists of a thousand wishful metal album covers scrawled across a thousand school exercise books. One image takes Brian Froud as its inspiration and by inspiration I mean that at its centre is one of his rather distinctive characters, economically traced, without credit.

Craft of the Untamed is better formatted than many Mandrake of Oxford titles, with none of the cramped styling that is usually found amongst their books. In place of it, though, and proving I’m never satisfied, is an overly generous leading that almost approaches double line spacing in depth and which, although allowing things to breathe, does result in just 30 lines of text on a page. This count is reduced even more when the style is applied to what ends up being rather spaced out invokations that can’t help but be read in a stilted, broken tone worthy of William Shatner. There’s an unfortunately typical lack of attention to detail in the formatting and proofing: chapter headings can’t decide if they’re meant to be bolded or not, the first page of each chapter flaunts convention and includes the header with the book’s author and title in it (as do all other pages, regardless of the content), and there’s a reckless disregard for punctuation, with a surfeit of missing, redundant or misplaced commas.

With its overgenerous leading, Craft of the Untamed makes for what feels like a slimmer volume than its tally of 180 pages would suggest. When this is twinned with Frisvold’s brisk style of writing, the reader can find themselves skipping quickly through the pages. As an overview of some of witchcraft’s themes, Craft of the Untamed meets its brief, and the point of difference, largely unpromised at the start, is a tendency to relate these to Western Occultism and Hermeticism, with Frisvold’s affiliation as a Traditionalist occasionally coming through via this approach.

Published by Mandrake of Oxford