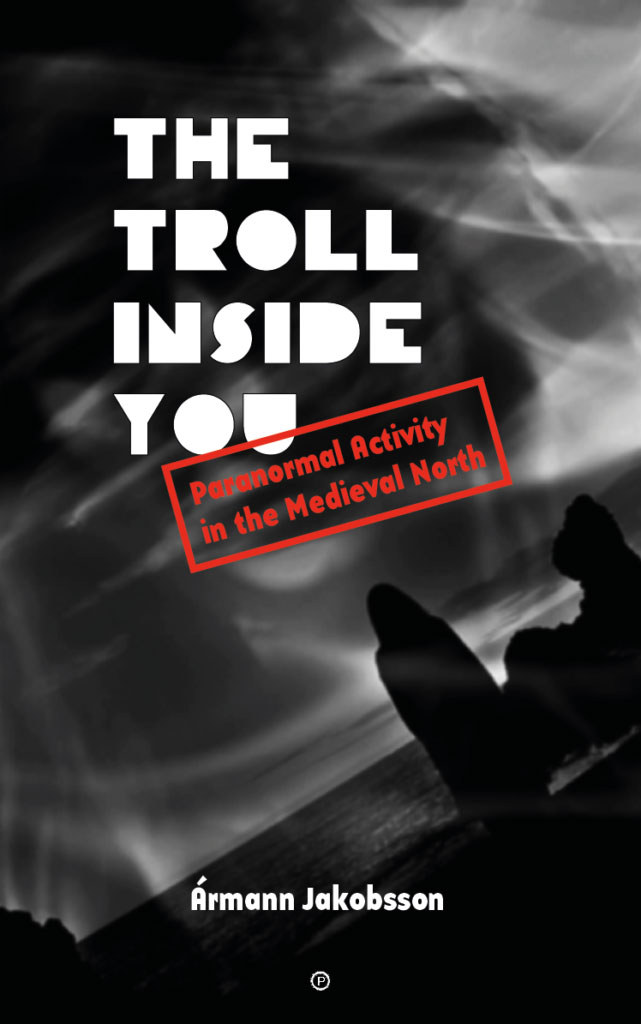

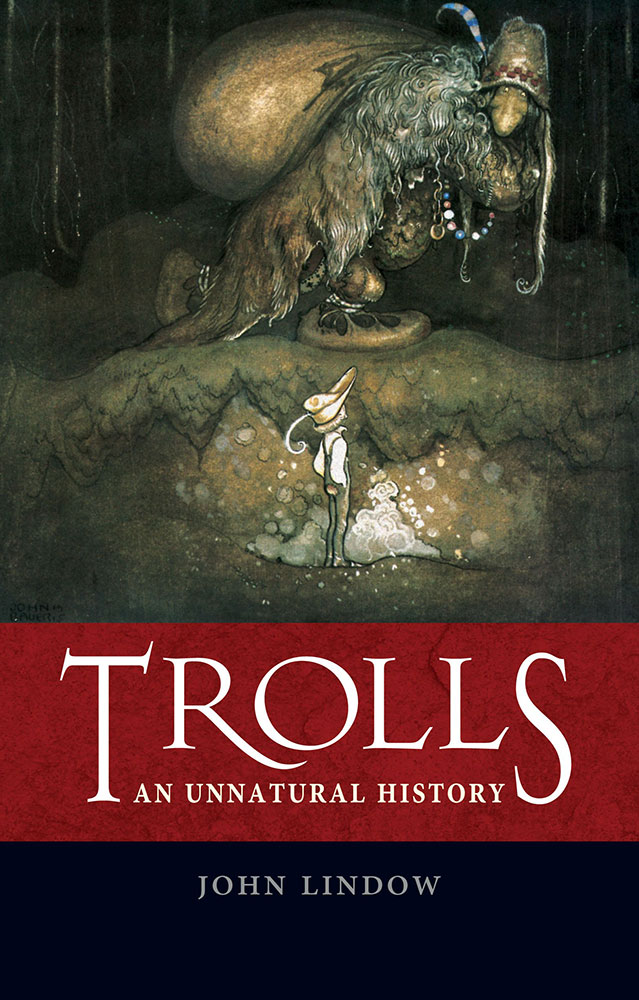

John Lindow, Professor Emeritus of Old Norse/Folklore at Berkeley, has a few significant academic contributions here on the Scriptus Recensera shelves, most notably his substantial Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Published by Reaktion Books, Trolls: An Unnatural History feels a little more public-facing, sitting alongside similar popular cultural history titles on the likes of dragons and other fantastic beasts. This is something suggested by the John Bauer painting from Bland tomtar och troll used on the cover, with its archetypal imagining of what a Swedish troll looks like, all immense hunched frame, large nose and shaggy hair. But there is more to trolls than this popular folk image, and as a result, there’s more to Trolls: An Unnatural History too.

John Lindow, Professor Emeritus of Old Norse/Folklore at Berkeley, has a few significant academic contributions here on the Scriptus Recensera shelves, most notably his substantial Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Published by Reaktion Books, Trolls: An Unnatural History feels a little more public-facing, sitting alongside similar popular cultural history titles on the likes of dragons and other fantastic beasts. This is something suggested by the John Bauer painting from Bland tomtar och troll used on the cover, with its archetypal imagining of what a Swedish troll looks like, all immense hunched frame, large nose and shaggy hair. But there is more to trolls than this popular folk image, and as a result, there’s more to Trolls: An Unnatural History too.

While there is noticeably more consideration within these pages of the Bauer-like troll of folklore, and that figure, fittingly, looms large throughout, Lindow provides a thorough consideration of the first trolls, those of the earlier Old Norse sagas. In these sources, beginning with a poem by ninth century court poet Bragi Boddason, trolls are defined by their indefinability, being creatures that are described in a variety of sometimes contrary ways, with the only consistency being their designation as Other. These trolls, rather than being the bogeyish figures of later folklore, are closer to gods, being forces of nature and the alterior, often synonymous with giants and other broadly defined eldritch beings of death, the wild and the cosmological landscape.

Lindow shows that these characteristics, this liminal insolubility, is not something incongruous with later folklore depictions of trolls (just as the various uses of the name in modern parlance can be read as relating, in various ways and degrees, to its original inscrutable descriptions; perhaps with the exception of the Trolls of World of Warcraft, you come get da voodoo). Indeed, the inability to control by definition made the term a catch-all one that could be as easily applied to a range of supernatural creatures as it had been in the Viking Age.

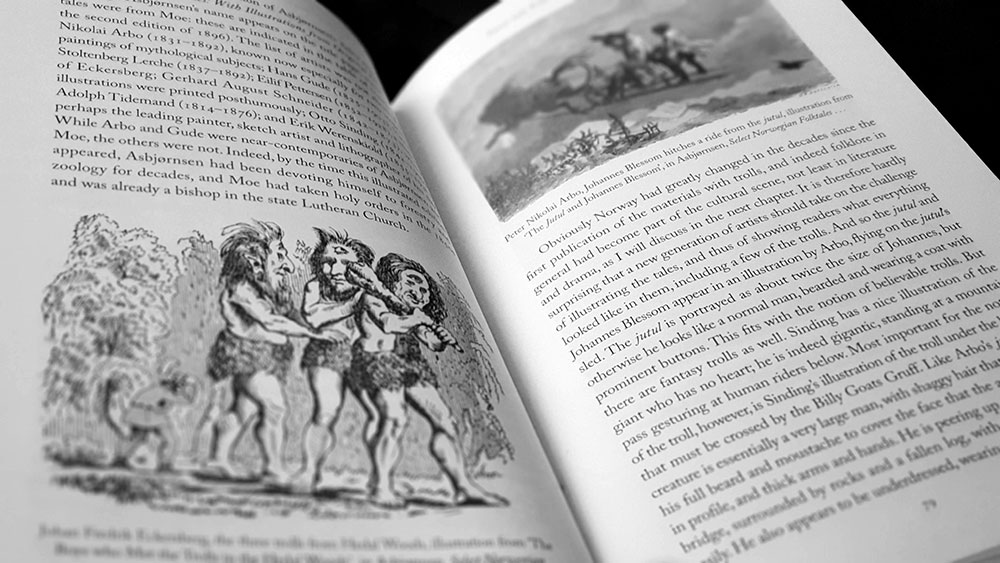

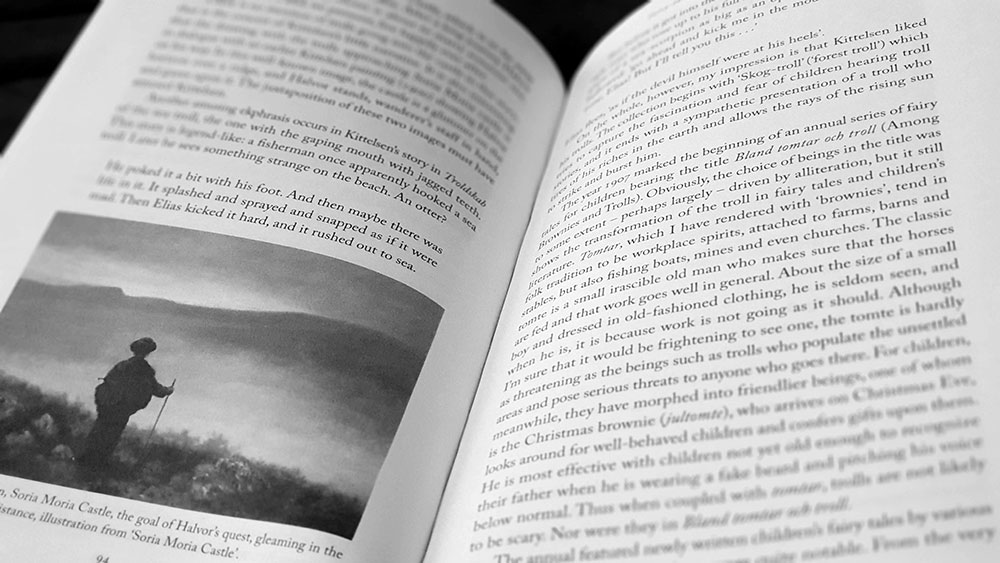

Perhaps the most enjoyable section of Trolls: An Unnatural History is the somewhat awkwardly titled fourth chapter Fairy-tale Trolls and Trolls Illustrated, which begins, as indicated, with a discussion of the evolution of trolls stories from folklore into the more codified realm of fairy tales. This is then followed by a thorough survey of how these literary illustrations were complimented by actual illustrations, in the works of such artists as Johan Fredrik Eckersberg, Peter Nikolai Arbo, Otto Sinding, Erik Werenskiold and Theodor Kittelsen. While we are dealing with single artists with singular visions, these images are interesting because they presumably do represent the multiplicity of ways in which trolls were visualised in the mind of nineteenth century Scandinavians. Lindow tracks this evolution of thinking, showing how the unresolved imagery of Eckersberg (in which trolls are largely just wild men) and other illustrators was gradually distilled into a very particular visual language, as seen in the work of Werenskiold and Kittelsen, with the troll’s corporeal monstrosity writ large.

Lindow notes that Werenskiold’s work contains a style of illustration (which would come to dominate in that of Kittelsen and others), which sees trolls emerging from and merging with the environment, a “blending of trolls with the materiality of the landscape.” Werenskiold uses the same cross hatching for wood as he does for the trolls that appear in front of it, while Kittelsen’s trolls are often show in symbiosis with the forests from which they issue, with relatively tiny trees and grasses growing on their mossy heads and backs.

After a discussion of trolls in literature (Ibsen’s Peer Gynt being perhaps the most notable example), Lindow gives a survey of trolls from a broader cultural viewpoint, in particular as they are marketed to children. This allows for brief mentions of works by the likes of Tolkien, Rowling, as well as a discussion of the familiar diminutive troll dolls and their then nascent feature film. He then concludes with an epilogue for the digital age, focusing on the use of ‘troll’ as a designation in digital discourse, where the characteristics of the Viking Age troll as an unwelcome and disruptive force from the outside have been renewed with vigour.

Sources are not cited within the body of Trolls: An Unnatural History and instead, Lindow uses an area following the epilogue in which, in sections for each chapter, he discusses the various sources, providing them with either broad context or as specific recommendations. This is an interesting way to do it, giving the reader the opportunity to look thoroughly at the source material, but without distracting the flow of the body with footnote, endnotes, or goddess forbid, in text citations. This reflects Lindow’s writing style throughout, which is popular rather than academic and theoretical, engaging the reader with an erudite manner that is still approachable.

Trolls: An Unnatural History binds its 160 pages and dark grey endpapers in a red cloth, with the title and author foiled in gold on the spine. This is then wrapped in a glossy dust jacket with the aforementioned image by Bauer on the front. Images are featured throughout, particularly in the fourth chapter with its focus on visual depictions of trolls.

Published by Reaktion Books