Blessed with a cumbersome title that surely no one has ever thought to use before, or since, Beowulf’s Ecstatic Trance Magic by Nicholas E. Brink is part of a metaphysical subgenre, pioneered by anthropologist Felicitas Goodman, in which it is argued that image of figures in ancient artworks are ritual instructions, providing templates for postures that could be used to enter altered states of consciousness. Goodman’s ideas were brought to a wider metaphysical audience in Belinda Gore’s Ecstatic Body Postures: An Alternate Reality Workbook (published in 1995 by the Inner Traditions imprint Bear & Company), while Goodman herself would release Ecstatic Trance: New Ritual Body Postures co-authored with Nana Nauwald in 2003. Others have since explored the theory, and while Goodman and Gore largely emphasise figures from Mesoamerica, Brink has taken a more European focus.

Blessed with a cumbersome title that surely no one has ever thought to use before, or since, Beowulf’s Ecstatic Trance Magic by Nicholas E. Brink is part of a metaphysical subgenre, pioneered by anthropologist Felicitas Goodman, in which it is argued that image of figures in ancient artworks are ritual instructions, providing templates for postures that could be used to enter altered states of consciousness. Goodman’s ideas were brought to a wider metaphysical audience in Belinda Gore’s Ecstatic Body Postures: An Alternate Reality Workbook (published in 1995 by the Inner Traditions imprint Bear & Company), while Goodman herself would release Ecstatic Trance: New Ritual Body Postures co-authored with Nana Nauwald in 2003. Others have since explored the theory, and while Goodman and Gore largely emphasise figures from Mesoamerica, Brink has taken a more European focus.

This is certainly not Brink’s first ecstatic trance rodeo either, having previously published three such titles, The Power of Ecstatic Trance, Trance Journeys of the Hunter-Gatherers and Baldr’s Magic: The Power of Norse Shamanism and Ecstatic Trance. Despite the Baldr of the title, the latter book has cover art featuring the ithyphallic Rällinge statuette, usually assumed to depict Freyr, but oh well, never mind as that’s nothing compared to a more recent outing from Brink, called Loki’s Children, which has a figurine from the Pre-Columbian Zacatecas culture as its cover star.

Unlike other titles in this genre, Beowulf’s Ecstatic Trance Magic is not a practical guide, and offers something rather different, with what little instruction there is being largely embedded within a fictionalised narrative. We say fictionalised but Brink presents it as a real account, channelled through him by its participants, and thereby effectively testifying to the efficacy of the system of ecstatic postures as a way to connect with the past. This is not a new writing approach for Brink as his Baldr’s Magic, whilst featuring some practical instructions, had as its lion’s share an entire Lost Edda of the Vanir, all channelled to him during his trance experiences.

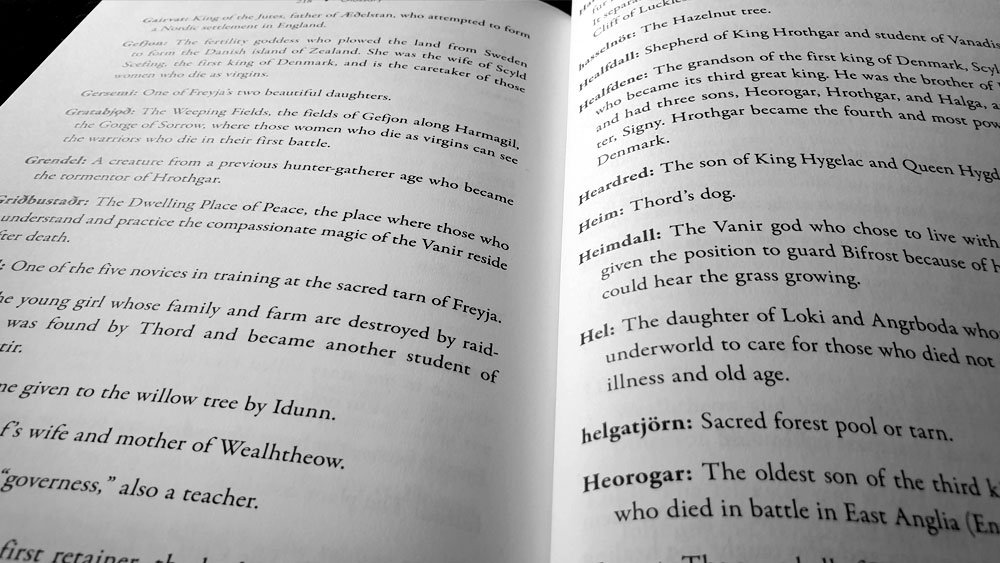

The story that Beowulf’s Ecstatic Trance Magic tells begins not with the Beowulf of the title, but rather with Wealhþeow, as Brink’s channels a narrative describing the early life of the girl that would become queen to Hroðgar, the Danish king who employed Beowulf to kill the monster Grendel. In Beowulf, Wealhþeow is a member of the Wulfings, though the poet does not locate the clan geographically, with other Scandinavian sagas associating them with the Swedish province of Östergötland, while more recent interpretations identify them with the Wuffing dynasty of East Anglia, at whose court the poem may have been composed. While Skjöldunga saga tells how Roas (Hroðgar) married the daughter of an English king, and Hrolfs saga kraka, says that he (named Hróarr in the text) married the daughter of a king of Northumbria, Brink goes with a Swedish interpretation, placing young Wealhþeow in Scania as the daughter of a King Olaf. Joining Wealhþeow in this cast is a priestess of Freyja who is rather awkwardly called Vanadisdottir, with a matronym used as if it was her first name. Although this is no less awkward than having a Swedish princess being incongruously addressed throughout by the Anglo-Saxon name she would only be given two centuries later by the Beowulf poet. As an aside, Brink acknowledges that Vanadisdottir, along with two other shamans who provide perspectives, Healfdall and the patronym-as-first name Forsetason, were unnamed in his initial experiences until he himself named them; a strange omission for the etheric realm to make.

Brink’s story is principally told from the perspectives of Wealhþeow and Vanadisdottir, charting the latter’s journey to the role of queen and the former’s role first as an advisor to her charge and then as someone who comes to understand Grendel and his predations. And yeah, about that… this version of Grendel seems to have undergone a Disney-style sympathetic villain reboot. No longer is he a mere despoiler of Heorot, and instead of being a deaþscua (‘death-shadow’) and helle gast (‘hellish spirit’) descended from Cain, he is a gentle creature who keeps to himself unless provoked by the warriors in Heorot and their raucous goings on. And while he might attack those who lust for power and wealth and seek to control the earth, this kinder, cuddlier Grendel doesn’t prey on farmers and those at one with nature and all its lovely creatures.

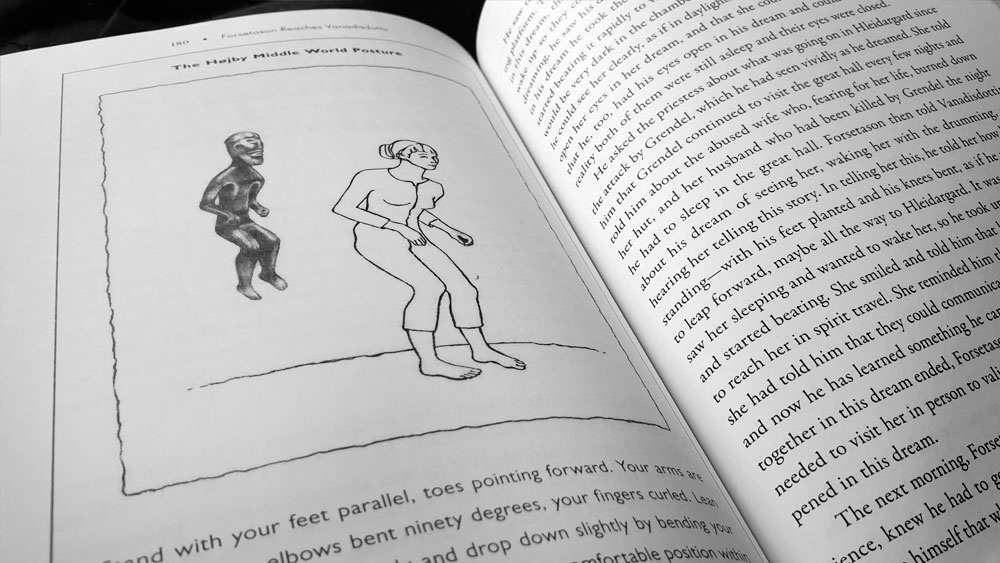

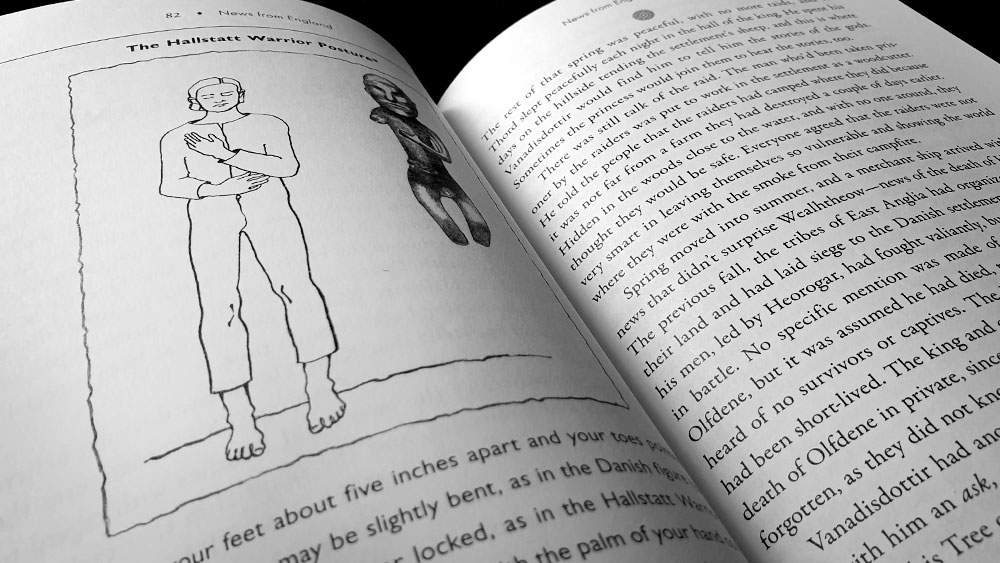

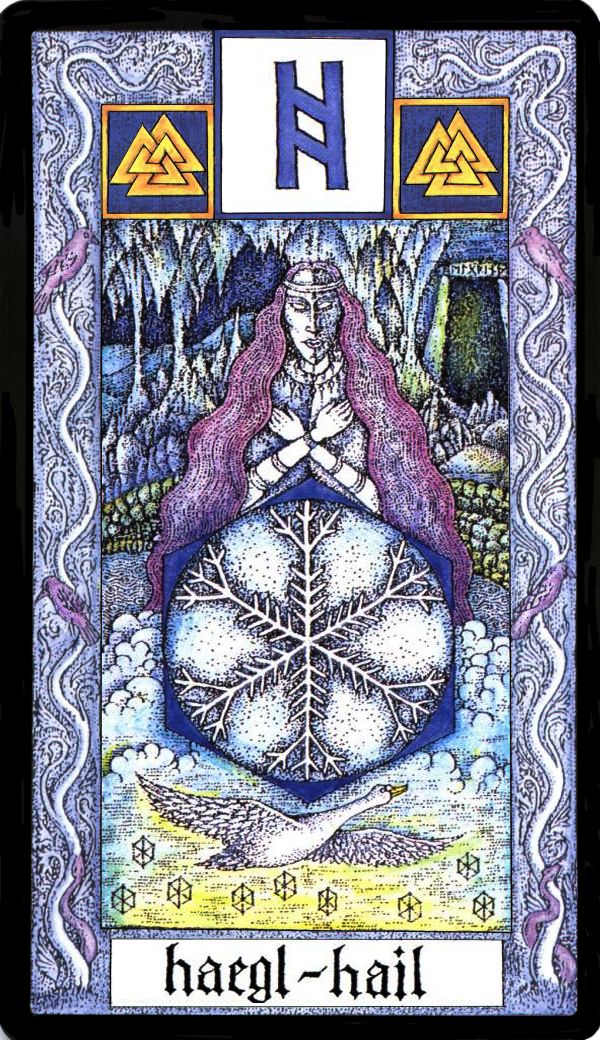

As the story progresses, Brink has Vanadisdottir introduce ecstatic postures as part of the narrative, with each presented as a full page diagram with instructions and a little footnote giving its provenance. There are ten postures in all and they are drawn from geographically, culturally and temporally diverse sources; though mercifully, none as far afield as Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. There is what Brink calls the Freyr Diviner posture (based on aforementioned ithyphallic Rällinge statuette), the Bear Spirit posture (a healing posture identified and named as such by Felicitas Goodman), the Sami Lowerworld posture (based on a engraving of a prone noaidi from Johannes Schefferus’ 1673 book Lapponia), the Tanum Sky World posture and the Tanum Lower World posture (both taken from amongst the many Bronze Age petroglyphs at Tanum, Sweden), the Hallstatt Warrior posture (which, contrary to the name of the posture, is based, though uncredited, on a figurine found in Bregnebjerg, Denmark), the Freyja Initiation posture (based on the famous pendant found at Aska, Sweden, that is assumed to be of Freyja), the Nyborg Man posture (based on a small gold figure, found at Nyborg, Denmark), the Højby Middle World posture (based on a figure found at Højby, Denmark, and which is also used on this book’s cover), and the Cernunnos Metamorphosis posture (as seen in the horned figure on the Gundestrup cauldron).

Surprisingly, given his starring role in this book’s title, it takes until page 202 for Beowulf to turn up as an active participant, almost as an afterthought with only twelve pages to go. One supposes that his name has a greater cachet than the less recognisable and less marketable Wealhþeow or Vanadisdottir, but given that he’s the one with the ecstatic trance magic in the title, you can’t help feeling a little swerved. This is especially so when it turns out how he doesn’t do any ecstatic trance magic at all, and everything pretty much proceeds as the poet told it: Grendel attacks, Beowulf fights him until the monster flees mortally wounded, and then Grendel’s mother seeks revenge on Heorot the following night and is also killed by Beowulf. The only difference is that Brink’s Vanadisdottir is flitting around being a little concerned and sympathetic, since Grendel is just misunderstood, but doing nothing.

Brink’s narrative is certainly detailed but it ultimately doesn’t ring true and feels like fan fiction or a first attempt at a fantasy novel. All the tropes are there: the headstrong princess who nevertheless has obligations to destiny and family, the oh-so-wise spiritual elder who teaches lessons of both life and magic with a matter-of-fact manner and a knowing smile. Even the embedding of actual techniques into the conceit of a historical story seems like something we’ve seen before, think The Way of Wyrd by Brian Bates, for example.

Another issue that will gnaw away at the pedant is that Brink presents his characters and their beliefs as if Germanic pagan belief was geographically monolithic, with the same pantheon and myths spread across the population, whether the stories be told in Sweden, Denmark, or Snorri Sturluson’s post-conversion Iceland. Indeed, Snorri is important to mention here because the myths as they are told by Brink’s characters have the relative coherence of Snorri’s eddas: gods have very defined roles and their stories are clearly told, reflecting what we now know of them with centuries of hindsight, but which may never have existed in such a way for the people of Denmark at the time. There’s no suggestion, for example, of the variations of the tales as told by Saxo Grammaticus in his Gesta Danorum, with Baldr being imagined here as a compassionate milquetoast in a loving relationship with Nanna, rather than, as Saxo tells it, the unsuccessful suitor of Nanna who battled his rival, the successful Höðr, as a result. The only variance from a Snorri-style canon is when Brink applies his own unverified personal gnosis to this mythic structure, filling in the gaps to fit his proclivities, such as categorically classifying Ullr, Nanna and Heimdallr as Vanir, or saying that Baldr and Nanna lived separately, he in Ásgarðr and she in Vanaheimr. There’s also Brink’s creation of a whole new goddess called Moðir, carried over from his previous works, who is portrayed as an overarching mother earth goddess and the grandmother of Freyja and Frey, having married a giant called Slœgr (a name which Brink translates as ‘the creative one,’ rather than the usual but less palatable ‘sly’). Brink also extrapolates on some myths and adds a bunch of new locations that are not found in canon, with awkwardly and inconsistently spelt names, such as Gratabjöð (the Weeping Fields of the goddess Gefjon where she cares for those who die as maidens), Griðbustaðr (another afterlife destination but for those who worship the Vanir), and Gæfuleysabjarg (a cliff in Freyja’s domain where the souls of warriors unlucky enough to die in their first battle reside). Finally, there are some other bold claims, such as making the young Wealhþeow the weaver of the famed Överhogdal tapestries, something which would be quite a feat considering that their creation has been carbon dated to between 1040 and 1170 CE, four centuries later than the period during which Beowulf occurs.

For this and his other books, Brink seems to have spent a lot of time in the Freyr Diviner posture receiving transmissions from an unfamiliar past, or less generously, just making a lot of stuff up. For the sheer time and effort he is to be commended, but mileage may vary as to how far one is willing to take his unverified personal gnosis, especially when his narrative doesn’t distinguish between it and documented lore. Also, as an indicator of the overriding vibe here, the brief bibliography has few texts relevant to this book’s subject (save for two Beowulf titles and one on Scandinavian petroglyphs), with the rest being works on ecstatic body postures and a bunch of new age titles from the likes of Barbara Hand Clow, Rupert Sheldrake and Erwin Laszlo. Brink ends his book with hope for the kind of world Vanadisdottir and Wealhþeow believed in and discusses the great turmoil of our time with a reference to one of Laszlo’s titles. Therein, Laszlo promised that this chaos is just a period of transition to be endured and that a new world of peace will emerge when it all passes in 2020. I wonder how that turned out.

Beowulf’s Ecstatic Trance Magic runs to 235 pages with a cover design by Peri Swan (images courtesy of iStock) and internal artwork by M. J. Ruhe. Layout by Virginia Scott Bowman has the body typeset in Garamond and Gill Sans, with the latter and Bougan Black used for display.

Published by Bear & Company