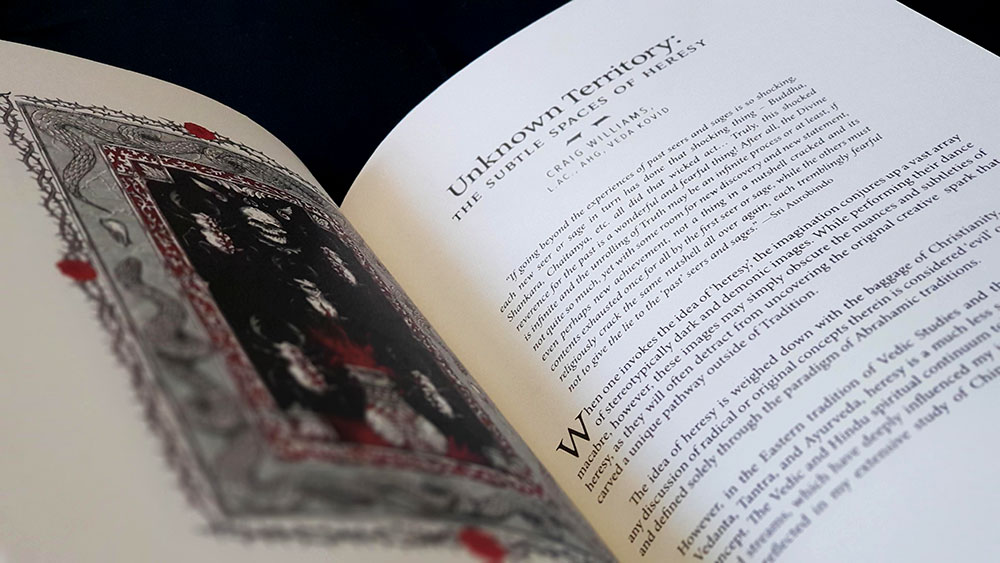

In the preface to Orpheus and the Roots of Platonism, Juan Acevedo, director of the publisher Matheson Trust, provides an initial outline of the work, being one in which, he says, Dr. Uždavinys’ intoxicated enthusiasm for his topic is tempered with a need to carry out exposition in a discursive and academic manner. It is a work which, would you believe, moves uneasily between the apophatic and the cataphatic, and we all know what kind of shenanigans that leads to. No? Alrighty then.

In the preface to Orpheus and the Roots of Platonism, Juan Acevedo, director of the publisher Matheson Trust, provides an initial outline of the work, being one in which, he says, Dr. Uždavinys’ intoxicated enthusiasm for his topic is tempered with a need to carry out exposition in a discursive and academic manner. It is a work which, would you believe, moves uneasily between the apophatic and the cataphatic, and we all know what kind of shenanigans that leads to. No? Alrighty then.

Orpheus and the Roots of Platonism runs as a single, 99-page monograph, divided into 24 chapters or sections that are given titles in the contents page, but infuriatingly, not in the actual body. Without these appearing within the body, the journey that Uždavinys takes the reader on can feel a little unstructured, as he jumps from one topic to the other without preamble. Laborious though it is, it becomes helpful to flip back to the contents page when encountering a new chapter, just to give you a sense of what is coming; and even then, that sometimes helps little.

Its sub-100 pages belie this volume’s density, with Uždavinys employing a multi-layered, polymathical style of writing that crams the pages with as much information as possible and often seems to divert into detail. Conversely, though, Uždavinys avoids using any theoretical framework or providing definitions of terms, so his highly specialised lexicon can be intimidating for those not familiar with it. Contrary to the title, there’s not always a lot of Orpheus involved, and this is no clearer than in the first chapter which begins, sans Orpheus, with a discussion of madness as a melancholy-like gift of the gods that can be poetic, telestic or prophetic (poietike mania, telestike mania and mantike mania).

Indeed, the roots that Uždavinys speaks of are more likely to be found in Egypt and more broadly, Mesopotamian, most notably Babylonia and Assyria. Even here, though, Platonism itself begins to lose its status as the focus of the text with Uždavinys spending an inordinate, though enjoyable, time considering the nature of prophecy and divine utterances in ancient Mesopotamia. These mantic experiences are explored exhaustively and range from the kind of channelled material generated by priests and priestesses standing within temples and embodying the gods, to local prophets who received messages from the gods involuntarily. This thorough exploration is divorced from what one would assume, given the title, is the focus of the book, and when Uždavinys does make reference to parallels in Greece he uses the rather less than satisfying, and possibly euphemistic, example of Pythagoras teaching from behind a curtain.

That isn’t to say there isn’t any mention of Orpheus or Orphism here, and the following four sections explicitly bear his name in their titles. Given the scarcity of extant information about a mythic figure like Orpheus though, and the lack of definition Uždavinys gives in turn to Orphism, these sections are brief, considerably more so than those that precede and proceed them, before yet another tangent is enthusiastically and abruptly pursued.

To return to the introductory words of Juan Acevedo, whether Orpheus and the Roots of Platonism does indeed move uneasily between the apophatic and the cataphatic this reviewer cannot say for sure, but it does succeed in its inability to sit still, ensuring that little gems spark interest amongst the turmoil of Uždavinys’ generously-described “discursive manner.”

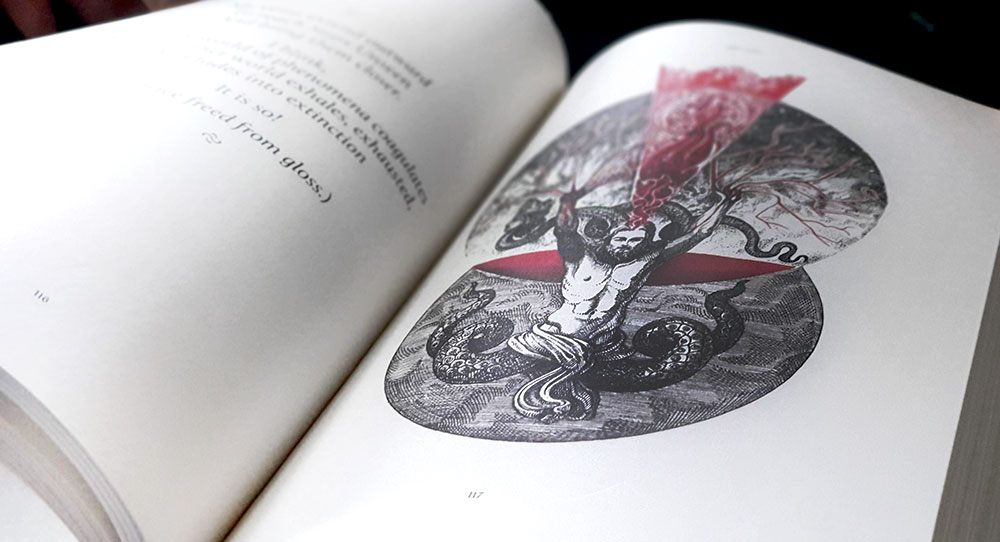

With the expectation generated by the title ignored, what Uždavinys provides is an interesting consideration of a variety of matters of interest to the esotericist, whether it be prophecy, initiation, divine inspiration, cosmology and eschatological conceptions of the soul. That these are hidden away within Uždavinys’ somewhat desultory text may make the journey all the more satisfying.

Published by the Matheson Trust