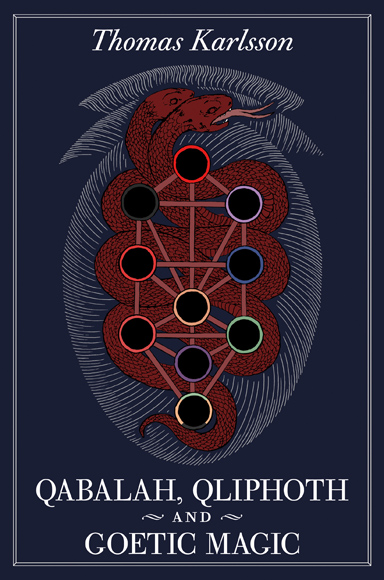

In this slim volume published by Fall of Man, Ophis Christos presents the philosophy of their Ordo Volucer Serpentis. Very much in the misanthropic vein of the Temple of the Black Light, the philosophy of the OVS is a version of Gnosticism in which the Gnostic hatred of matter, whether it be the incarnation of the spirit within a human body, or the creation of existence in general, is given full reign. The creator of this world is seen as a demiurge (paralleled across cultures in figures such as Ahura Mazda, Brahma, as well as the Judaeo-Christian god), who, in their misguided attempts at creation, acted as a force of limitation, imposing stagnant order upon limitless chaos.

In this slim volume published by Fall of Man, Ophis Christos presents the philosophy of their Ordo Volucer Serpentis. Very much in the misanthropic vein of the Temple of the Black Light, the philosophy of the OVS is a version of Gnosticism in which the Gnostic hatred of matter, whether it be the incarnation of the spirit within a human body, or the creation of existence in general, is given full reign. The creator of this world is seen as a demiurge (paralleled across cultures in figures such as Ahura Mazda, Brahma, as well as the Judaeo-Christian god), who, in their misguided attempts at creation, acted as a force of limitation, imposing stagnant order upon limitless chaos.

The return to the origin of the book’s subtitle is, then, the idea of undoing creation to return to a primordial state of chaos. This can make for rather bleak reading, such as when Christos writes: “As we look at this world, we comprehend that it would be better if it had not existed, therefore our essence and our will in truth is of the uncreated light.” Indeed. Quite what you do with such a worldview on a practical level is hard to grasp. I mean, unless you’re getting a job at CERN and tinkering with the Large Hadron Collider during out-of-office hours, there’s probably no real chance of destroying all creation. It is intriguing how the life-denying beliefs of the Gnostics have found resonance with the misanthropy of this rather metal-spirited form of Satanism and I remain as baffled about what modern adherents do after arriving at this worldview as I do trying to work out what Gnostics of 2000 years ago would have done on a practical level having reached the same conclusions.

Instead of giving a guide to gainful employment with CERN, The Ophidic Essence provides a summary of various strands of their anticosmic philosophy, seeing traces of similar ideas not just in Gnosticism but in mythological and metaphysical systems from around the world. Shiva and Kali represent the Hindu version of these unravellers of cosmic order, and their equivalent forms in ancient Mesopotamian mythology and Zoroastrian cosmology are considered as well. Christos moves on to explore the mythology of the Etruscans, who he categorises as a likeminded culture focussed on death, who saw value in the transition beyond this life, and distained the addiction to the limitations of this physical world. As examples of this focus, Christos considers two Etruscan psychopomp figures, the goddess Vanth and the daemon Charun, and then also briefly looks at the enigmatic figure of Tuchulcha.

Following this cross-cultural survey of anticosmic thought, The Ophidic Essence provides a practical element with magickal trope du jour, African diasporic religions, which in this case, is the Brazilian system of Quimbanda. Quimbanda is strongly defined within this text as a system separate from the related form Umbanda, with the latter cast as a scion of Christianity, whilst Quimbanda is seen as independent and drawing on energies from Sitra Ahra, the other side. As N.A.A.218 did in the first volume of Liber Falxifer, Christos presents a series of folk magick spells to give a sense of praxis associated with the Exus of Quimbanda, all very candles, tobacco smoke, votives and sigils.

The consideration of Quimbanda takes up half of this book and represents the largest focus on a single topic. In itself, it is divided into two sections, the aforementioned first half, and then a larger consideration of how this system and its exus and pombas can be related to Sitra Ahra. Here, various paths of Pomba Gira are likened to Lilith, while Lucifer finds his obvious place in Exu Maioral Lucifer. The odds of these rituals bringing about anticosmic dissolution seem fairly remote, but what is presented is a nice internally-consistent system of magick that is at least, thematically apposite to the attitudes conveyed throughout the book.

The Ophidic Essence is bound in black faux crushed leather card with 85 perfect bound pages and is limited to 300 hand-numbered copies. Although slight in size and length, it provides a good summary of the misanthropic philosophies of the OVS and similar orders. For those who resonate with such ideas, this will be recommended reading. Available from Fall of Man