We stray a little from the usual matters magickal with this review of the first issue of Punctum Book’s journal of black metal theory. Helvete is a collection that is, to my surprise, no means unique, with academic interest in black metal having previously found expression in several iterations of the Black Metal Theory Symposium, with those contributions anthologised in publications such as Hideous Gnosis and more recently Mors Mystica. Black metal must surely be unique amongst all of metal’s subgenres in attracting this kind of academic attention, and to some extent this is understandable with black metal’s caché of cool, or at the very least its memeability; were such a word real. No one, as far as I am aware, is out there writing academic theses on grindcore, or even comparable subgenres, in terms of longevity and quantity, like death or doom metal; which is a shame.

We stray a little from the usual matters magickal with this review of the first issue of Punctum Book’s journal of black metal theory. Helvete is a collection that is, to my surprise, no means unique, with academic interest in black metal having previously found expression in several iterations of the Black Metal Theory Symposium, with those contributions anthologised in publications such as Hideous Gnosis and more recently Mors Mystica. Black metal must surely be unique amongst all of metal’s subgenres in attracting this kind of academic attention, and to some extent this is understandable with black metal’s caché of cool, or at the very least its memeability; were such a word real. No one, as far as I am aware, is out there writing academic theses on grindcore, or even comparable subgenres, in terms of longevity and quantity, like death or doom metal; which is a shame.

Given the wealth of material already, erm, symposiumed and published, one would assume that the entry level, what-is-black-metal type discussions in this field would have been published long ago, if at all, and that is indeed the case here, with contributors exploring rather specialised areas of black metal’s topography. With that said, the first contribution, Janet Silk’s Open a Vein, does contextualise her discussion of suicide and black metal by setting the scene with the suicide of Mayhem’s Per ‘Dead’ Ohlin, a moment she describes as the birth of black metal (an urbane albeit arguable and problematic claim). Silk prefaces much of her consideration of depressive suicidal black metal (which she atypically abbreviates as the less recognisable SBM) with a survey of suicide in philosophy, religion, and other cultures, touching on Mishima and the death-drive of early Christian martyrs and Islamic šuhada. She does this in a slightly unnervingly amoral way, with what can be read at the very least as an admirable detachment with no moral judgement cast, and perhaps at worst, as a tacit approval of, or admiration for, suicide’s destructive and nihilistic impulses. I, in turn, make no moral judgement on this editorial choice and just reiterate the disconcerting feeling that inescapably arises when reading content that seems to sensibly suggest suicide is a good option. When DSBM is then considered within this context, its themes and motivations are validated as part of this greater milieu and given gravitas and import, rather than dismissed as mere posturing or angst. Silk’s main touchstone here, other than Dead, is Sweden’s Shining, and Denmark’s cheerfully named Make a Change… Kill Yourself, so it is by no means a broad survey of the sub-subgenre that is DSBM. Even if it wasn’t intended as such, it feels like some areas have been missed: the suicide of Dissection’s Jon Nödtveidt and how the anticosmic philosophies of the Temple of the Black Light compare to the nihilism of the musicians that Silk does document; or the isolation that is inherent in so many DSBM acts being solo projects by secluded, socially-awkward multi-instrumentalists.

The esteemed Timothy Morton finds a good springboard for his talk of hyperobjects and dank ecology in Wolves in the Throne Room, whose status as arch conservationists provides the basis for much of his musings. Despite being the Rita Shea Guffey Chair in English at Rice University, Morton’s paean to Wolves in the Throne Room feels more like a creative writing exercise, or the worst kind of music review in the world. You know the kind? The kind that describes the scenes that the music paints in the reviewer’s mind, rather than just saying what it sounds like. Do you know what is also annoying? All the questions. What’s the deal with that? Morton jumps around like he’s over-caffeinated, pre-empting all his conclusions with questions to the mute audience. When are we? Where are we? Why a pool of death? Why indeed. This works well when it is used initially for musings on the open-ended ambiguity of the band name (whose throne room, who are the wolves, are they welcomed, or invaders, or are they the original occupants?), but when page after page is peppered with not-rhetorical-but-sounding-rhetorical questions, it begins to grate. In the end, the questions, and indeed the wolves in this here room for a throne, tend to fade in favour of what comes across as talking points from Morten’s previous and voluminous discussions of a dark ecology without nature, barely tethered to the discussion of the band.

The most enjoyable contribution here comes from David Prescott-Steed with Frostbite on My Feet: Representations of Walking in Black Metal Visual Culture. Perhaps this is because it is a meditation on something so simple, and yet so quintessentially, but not obviously, black metal. After all, who can imagine a black metal musician in a car? Inconceivable.¹ Prescott-Steed explores the theme of walking from multiple angles, including the personal, where he talks of the experience of ‘blackened walking,’ his term for walking around the modern metropolis that is an Australian city, but listening to a headphone soundtrack of frosty cuts from Burzum, Gorgoroth and Mayhem. He incorporates Rey Chow’s analysis of the cultural politics of portable music into this, exploring the themes of incongruity and of the act of disappearing that is inherent in removing an awareness of one’s environs by imposing a personal soundtrack; a theme that, though Prescott-Steed doesn’t dwell on it, feeds back into black metal’s tortured relationship between the over and underground, between fame and infamy, elitism and the recherché.

Daniel Lukes’ Black Metal Machine is a survey of the industrial strain of black metal; cleverly acronymed as IBM. He begins with an extensive grounding in methodology and context, namechecking Deleuze and providing several literary precedents (Ballard and Vonnegut) that emphasise the dystopian, post-apocalyptic vision of the future, rather than a shiny chrome utopia. This he relates to the misanthropy of black metal, where the science fiction-tinged desolation of the future is but a slight twist of a standard black metal narrative of destruction and contempt for the world. As examples, Lukes considers Red Harvest (who get several pages devoted to them), Dødheimsgard, Arcturus and Spektr, while also briefly touching on Marduk as well as Impaled Nazarene’s themes of a comic and perverse Armageddon.

Joel Cotterell concludes this volume with a brief consideration of the motif of the dawn in black metal, using tracks from Primordial, Satyricon, Inquisition and Nazxul as exemplars. Cotterell argues that the concept of dawn in black metal has a Luciferian component, denoting the rise of Lucifer as the morning star. Whether this interpretation of a less than rosy fingered dawn can be consistently applied to the over 400 songs that they found on metalarchives.com with dawn in the title is not addressed.

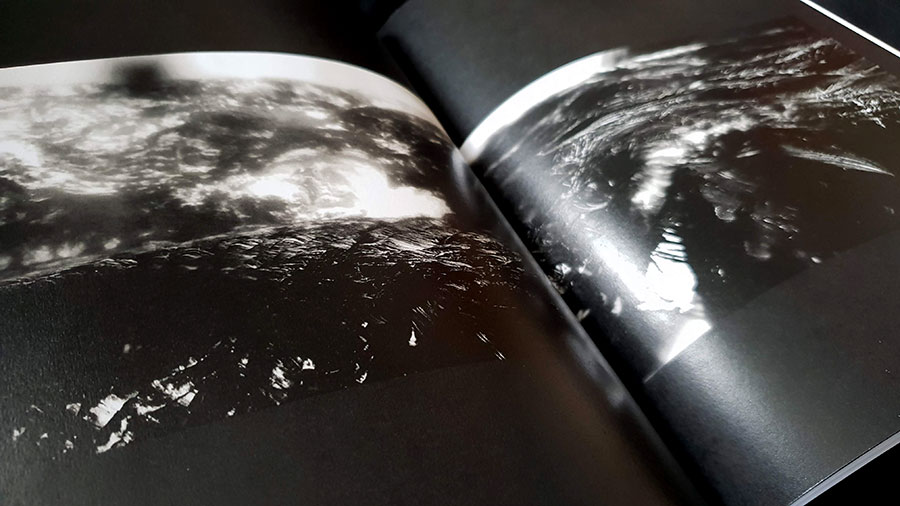

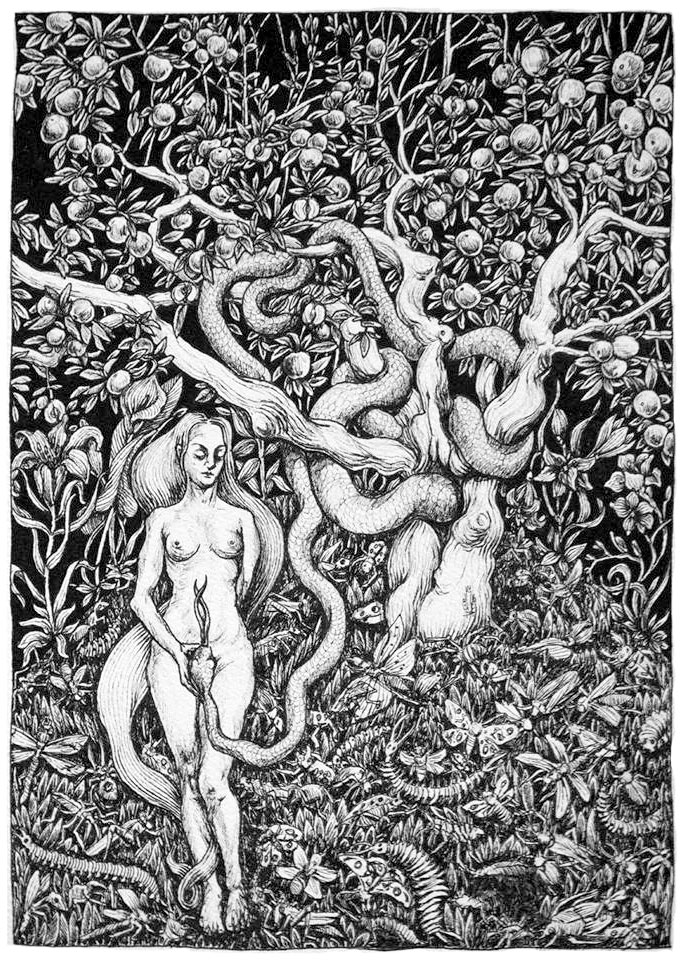

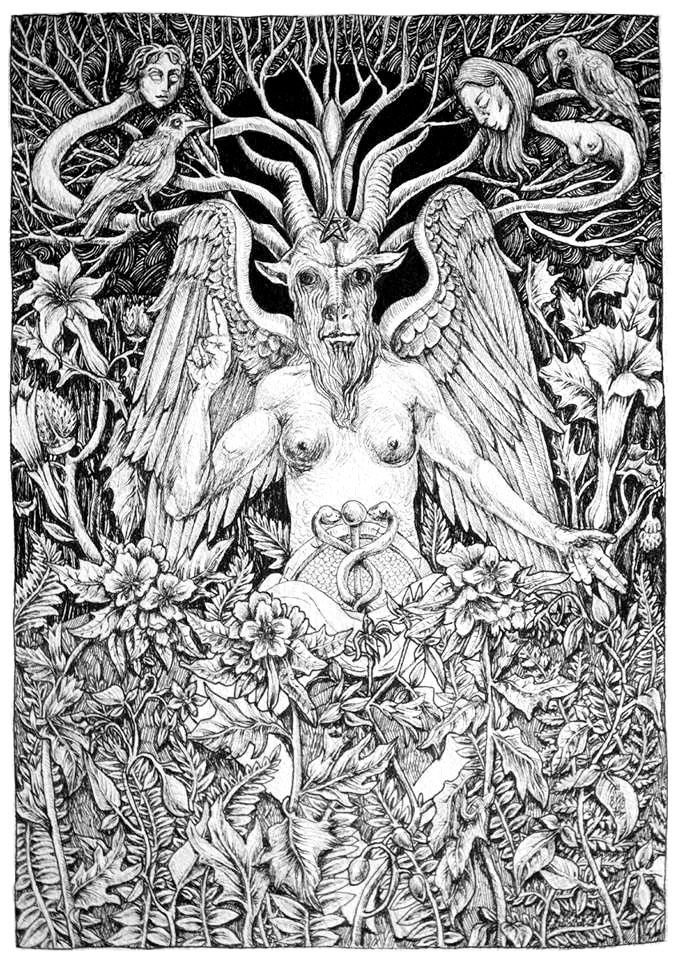

In addition to the written component, Helvete contains a section of black and white photographic plates curated by Amelia Ishmael and titled The night is no longer dead, it has a life of its own. The nine artists attempt to evoke black metal visually with an emphasis on obfuscation through texture, meaning that there’s nothing too obviously black metal here, with only two densely rendered black ink forms (care of Allen Linder, see above) and one foggy landscape. Some of these are more successful than others, with the gems being Gast Bouschet and Nadine Hilbert’s images of Grímsvötn in Iceland, darkened to the point of abstraction but animated with emanations of effusive light.

There are some persistent little quirks about this book that irritate and makes you wonder how, in the parlance of the genre, ‘true’™ it is. Norway looms large within the pages and it is referred to by multiple authors as the home of black metal; not second wave black metal but apparently black metal in general. In another case, black metal is referred to as being “for the most part, exclusively Western” with the gracious caveat that it has since inspired international contributions in the last twenty years (Colombia and Taiwan being presented as the examples of amazing outliers). This overlooks the non-Western bands, most notably from South America and Asia, that thirty and more years ago were contributing to and influencing black metal. That this point of Western-ness is made in attempt to prioritise Scandinavian aesthetics as the aesthetics of black metal seems indicative of the tendency to fetishize the Norwegian strain of black metal above all else; implicit in the journal title. And it is the specifically Norwegian variant, there’s even little acknowledgement of what emerged from Sweden and Finland at the same time, perhaps because it never produced those memeable moments like a Varg Vikerness smirk or Abbath’s gurning visage.

In all, the debut volume of Helvete makes for a brisk read with its 100 pages, but does whet the appetite for more of this here black metal theory.

Published by Punctum Books

¹ The image of Snorre Ruch and Vikerness driving from Bergen to Oslo on the night of 10 August 1993 has always seemed wildly incongruous to me.