Readers of Kennet Granholm’s Embracing the Dark, a study of the Swedish magical order the Dragon Rouge published in 2005 by Åbo Akademi University Press, may experience a sense of déjà vu when opening Dark Enlightenment. Released as Volume 18 in Brill’s Aries Book Series, this is effectively a revised version of Granholm’s PhD-thesis, but one that has been a long time coming. Initially intended to be finished by 2007, this title would take seven years to be completed due to the constant revisions necessitated by Granholm’s acquisition of new information, resulting in a book that feels far more fleshed out and well rounded.

Readers of Kennet Granholm’s Embracing the Dark, a study of the Swedish magical order the Dragon Rouge published in 2005 by Åbo Akademi University Press, may experience a sense of déjà vu when opening Dark Enlightenment. Released as Volume 18 in Brill’s Aries Book Series, this is effectively a revised version of Granholm’s PhD-thesis, but one that has been a long time coming. Initially intended to be finished by 2007, this title would take seven years to be completed due to the constant revisions necessitated by Granholm’s acquisition of new information, resulting in a book that feels far more fleshed out and well rounded.

Granholm presents Dark Enlightenment as a consideration of contemporary esotericism, in which the Dragon Rouge is a particular exemplary case study. But with that said, considerably more time and ink is spent on the order specifically, rather than the general occult milieu from which it emerges. The book keeps much of the broad structure of Embracing the Dark, sharing many of the same chapter titles and sub headings, as well as the general content, but this is not simply an exercise in tidying up and adding a few more bits of information. Instead, much if not all of the content has been rewritten, with an improved and more considered flow, with less of the feeling of brisk literature reviews and the covering off of theoretical models that are seen in, and are characteristic of, the thesis.

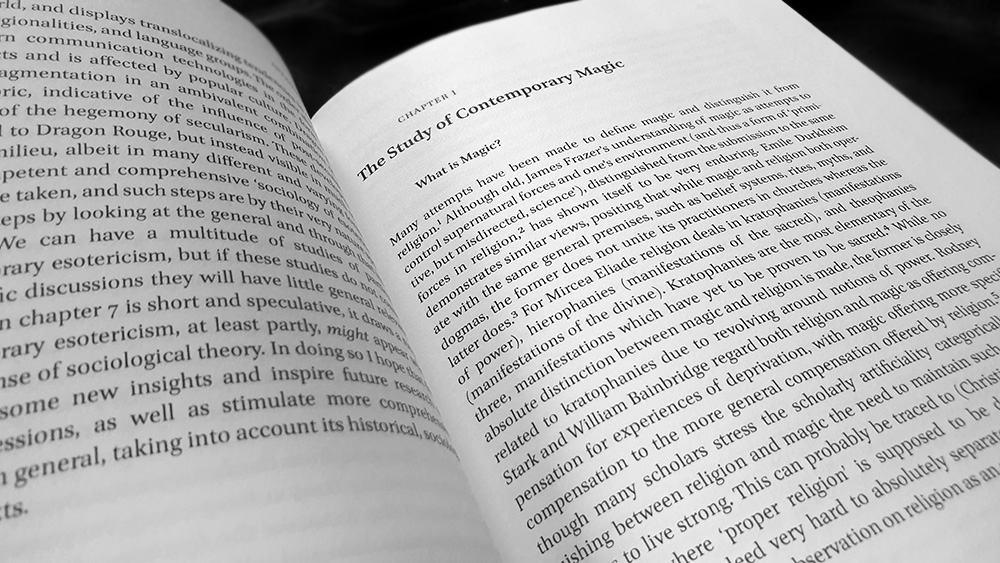

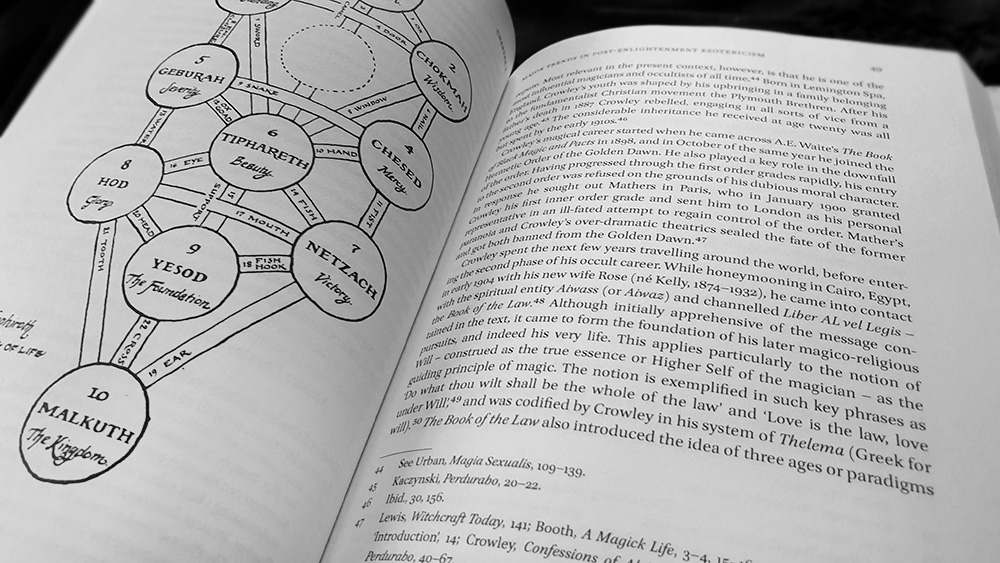

In the first half of Dark Enlightenment, Granholm does present a somewhat dry overview of esotericism leading up to the modern day. The first chapter is effectively a literature review, documenting the growth of esoteric studies within academia, marking off historiographical and sociological approaches, as well as the emergence within more recent years of what Granholm and Egil Asprem have termed a ‘new paradigm,’ as typified by the approaches of Wouter Hanegraaff, Christopher Partridge and Kocku von Stuckrad. It’s all essential academic grounding, but there’s no denying the sense of having to wade through the theoretical models to get to the good stuff. The same is also true of the following chapter on major trends in post-Enlightenment esotericism, beginning with Theosophy and the rest of the Nineteenth Century Occult Revival, and ticking off Neopaganism and Satanism before ending with the New Age and the mainstream popularisation of occultism. Once again, it is all necessary for context, but it is well-worn territory for anyone familiar with the Western history of occultism from across the last two centuries.

In Embracing the Dark, Granholm began his first chapter on Dragon Rouge by discussing its philosophical tenets, a decision that resulted in the order being somewhat temporally unmoored. Here, though, the chapter begins with the history of the order, acknowledging that any comprehensive consideration of Dragon Rogue needs to start with founder Thomas Karlsson. Indeed, one of the areas in which Granholm has added further details is in the story of Karlsson’s youth and what lead up to his founding of the Dragon Rouge. In Embracing the Dark, this section felt brief, even though all the significant moments were there, but here they are a lot more fleshed out. Notably, an early friend and occult influence for Karlsson, ten years his senior, who was previously unnamed and little credited, is now given a pseudonym (the suitably mysterious ‘Varg,’ would you believe) and receives multiple mentions as a formative influence. Similarly, further context is given to a story, briefly recalled in Embracing the Dark, about how a Draconian baptismal ceremony held by the order was mispresented by Göteborgs-Posten as a Satanic baptism, due, not to any content in the ritual, but because the parents themselves were Satanists. Now the previously unnamed father is identified as the singer of black metal band Dark Funeral (presumably Magnus Broberg, AKA Emperor Magus Caligula), which is just neat.

Granholm also has a slightly broader dataset than just the questionnaires and interviews from 2001 and 2002 that he drew upon for Embracing the Dark, now boosted with further interviews from between 2007 and 2012 with Karlsson and other Dragon Rouge members, as well as representatives of the Ordo Templi Orientis and the Rosicrucian Order of Alpha+Omega. The bibliography is also larger, reflecting the growth in esoteric academia, with references to Granholm’s own works, limited to just two entries in Embracing the Dark, now running to over a page.

In all, there seems to be a greater attention to detail throughout Dark Enlightenment, and with that comes a more circumspect and critical element added to Granholm’s assessment of the Dragon Rouge. While the 2005 iteration could feel overly-immersed in the order, all starry-eyed and accepting, now there’s more of an anthropological aloofness, an awareness that occultists should not be entirely trusted when it comes to anything, especially their own mythmaking. In one example, Granholm takes time to fact-check some convenient but inaccurate etymology in the order’s vision of the Dark Feminine, critiquing an article on Vamamarga Tantra from the order’s Dracontias publication in which ‘Vama’ is translated as ‘woman’ in order to emphasis the system’s feminine focus. This is a pleasing idea, but despite being superficially similar to an adjective used in compounds to denote female characteristics, the Vama component in Vamamarga is etymologically distinct and means ‘left’ or ‘adverse;’ as is appropriate for its use in the designation of left-hand path Tantra. In highlighting this little faux pas, Granholm questions the order’s choices, defining it as ‘interesting’ that the Dracontias author prioritises a tenuous etymology over more thorough evidence such as the many tantric texts that relate directly to the feminine.

Granholm peppers his analysis of the Dragon Rouge with quotes from its members who often come across as just a little insufferable. This is due to what one could call left-hand path arrogance, an undeserved confidence that comes from believing that your affiliation to an organisation that prioritises an antinomian spirit makes you unique and outside the bounds of normality; as if merely saying it makes it so. There’s the dismissive attitude to more light-aligned occultists, or the boasting about black magicians actualising by breaking free of imposed morality, ‘loving honestly’ with “a love for the living and not for the meek and dying.”

In his concluding remarks, Granholm does a reviewer’s job by mentioning gaps in his work, briefly discussing themes that could have been explored were it not for the constraints of time, space and focus. The first of these finds us in agreement over the missed opportunity to more closely examine Dragon Rouge within the broader Left-Hand Path milieu. Whilst there are passing references to other groups like the Temple of Set and the Church of Satan, these are largely confined to the overview provided by the Major Trends in Post-Enlightenment Esotericism chapter, and beyond that, Dragon Rouge seemingly stands alone. Less vital but still of interest, Granholm laments the missed opportunity of discussing more fully the intersection betwixt Dragon Rouge and academia, while its relation to pop culture (briefly touched upon when discussing its role in metal music) and gender theory are also acknowledged as areas that could have warranted more consideration.

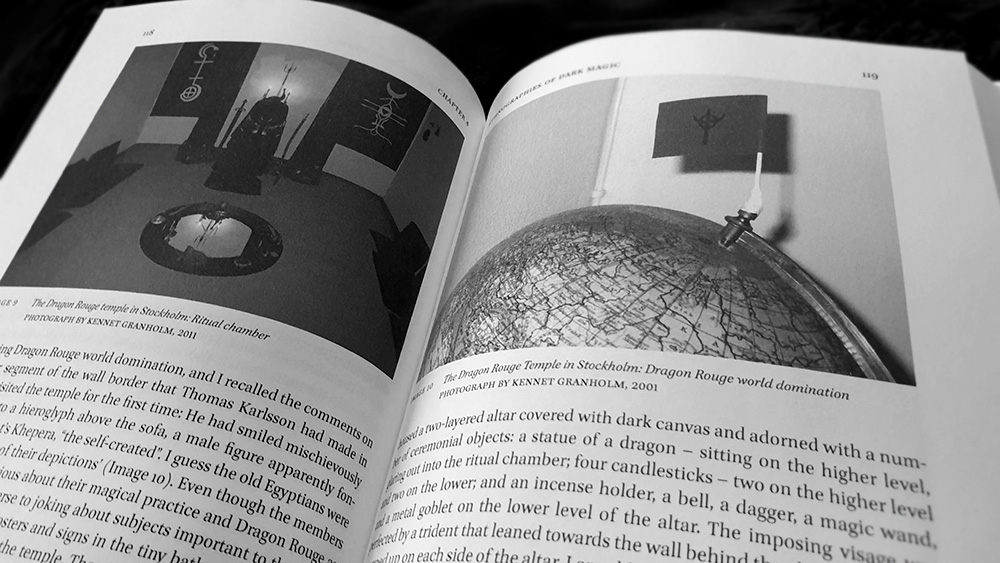

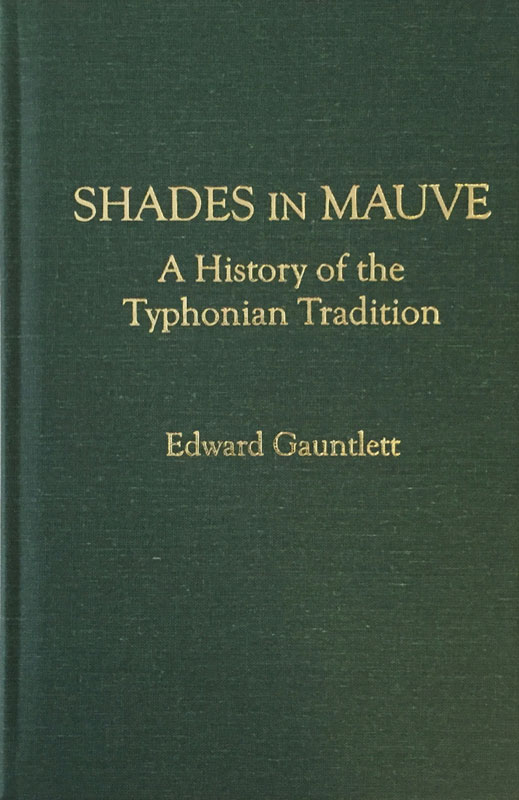

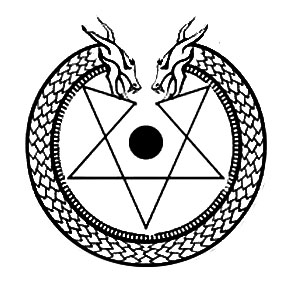

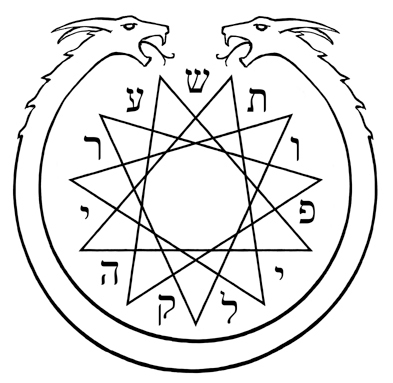

As one would expect, the extra time spent on Dark Enlightenment makes it a fine replacement of the formative thesis version, and an essential text as a case study of modern esotericism. It runs to 230 pages and is hardbound, with type setting in Brill’s unremarkable but readable house-style, with typeset in their custom eponymous typeface. Black and white photographs dot the Dragon Rouge section as well as a few black and white sigils.

Published by Brill