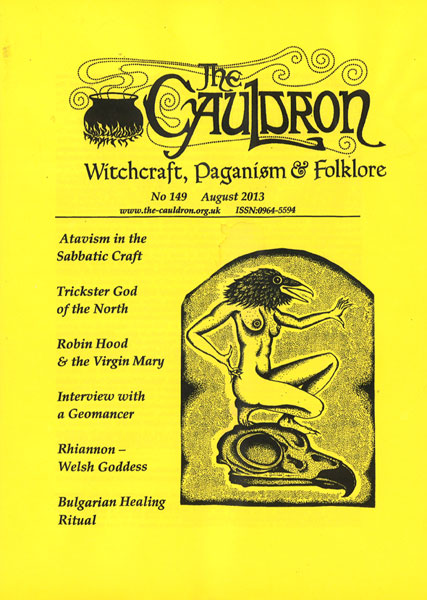

Reading the latest issue of Michael Howard’s magazine The Cauldron is a peculiar personal experience. The last time I read The Cauldron was 1996 and it seems that not a lot has changed. While fancy occult journals like Abraxas and Clavis have emerged in recent times with all their art papers and full colour pages, things have stayed humble at The Cauldron: simply reproduced and stapled, with exactly the same full-page, single-column formatting and font as it was almost twenty years ago. And that’s not such a bad thing. While the glitz and glamour of some occult journals is nice, there’s always the risk of all the polish masking the quality, or lack thereof, of the content. But in the case of The Cauldron, content is queen. There are no full page illustrations, no occult poetry, and no torturous attempts at esoteric obscuration.

Reading the latest issue of Michael Howard’s magazine The Cauldron is a peculiar personal experience. The last time I read The Cauldron was 1996 and it seems that not a lot has changed. While fancy occult journals like Abraxas and Clavis have emerged in recent times with all their art papers and full colour pages, things have stayed humble at The Cauldron: simply reproduced and stapled, with exactly the same full-page, single-column formatting and font as it was almost twenty years ago. And that’s not such a bad thing. While the glitz and glamour of some occult journals is nice, there’s always the risk of all the polish masking the quality, or lack thereof, of the content. But in the case of The Cauldron, content is queen. There are no full page illustrations, no occult poetry, and no torturous attempts at esoteric obscuration.

Back in 1996, The Cauldron felt rather informed by Robert Cochrane’s Clan of Tubal Cain. It was where I first encountered the writings of Evan John Jones, then magister of the Clan, and read about things like the Rose Beyond the Grave, which was very much analogous to my own practice at the time. In 2013, though, the underlying theme seems to be directed by another strain of traditional witchcraft, that of the Cultus Sabbati; although with a sample pool of one issue, that may be a hasty conclusion. Artwork by Daniel Schulke graces the cover and he also provides the lead article, Anatomies of Shadow, a consideration of atavism within magick in general and traditional witchcraft specifically.

There are, though, a wide range of contributors to The Cauldron, with a variety of topics discussed in several different styles. Highlights include Greg Hill’s consideration of Robin Hood as a devotee of the Virgin Mary in the earliest iterations of the legend (which he argues was a pagan precedent given a Christian gloss) while a wonderfully academic approach is taken by Bob Trubshaw in a piece whose subtitle predicts just how rigorous it is going to be: The Metaphysical Relocation of the Self in Ritual Narrative. In contrast, some ever so slightly entry level articles are provided by Heidi Martinsson and Frances Billinghurst who consider Loki and Rhiannon respectively. These are character studies and myth summaries which won’t provide anything new for people already familiar with those deities. Martinsson’s piece has a glaring error describing Skadi kidnapping and binding Loki, when all she did was place the serpent above his face once he was caught by the Aesir.

In Witchcraft in the West Country, William Wallworth contributes a summary of 19th and early 20th century witchcraft culled from local and national newspapers. This is an interesting collection that shows how witchcraft was viewed, one by the general populous, and two, by the judiciary. Most are court reports of prosecutions brought against people, not for acts of witchcraft, but for assaulting alleged witches (often featuring attempts to draw a witch’s blood, which appears to have been a popular cure against bewitchment). Suffice to say, the zealous witch-accuser did not find much sympathy within the rational court. This form of, how you say, witchcraft anthropology is also the approach of Georgi Mishev and Michael Howard, who both address different forms of apotropaic witchcraft. Mishev considers the underlying symbolism of a Balkan ritual for determining the source of a magickal attack, while Howard summarises a series of Berber procedures for warding against the Evil Eye and djinn.

A change of pace is provided by Voices from the West, an on-going series of interviews by Josephine McCarthy and Stuart Littlejohn with various practitioners of the Western magical tradition. In this issue, they talk with geomancer David Cypher, whose position as a non-publishing magickal practitioner is an interesting one.

In addition to full-length articles, The Cauldron has the occasional short pieces, sometimes credited to Howard and other times left uncredited, addressing various current topics, including in this issue a tribute to Patricia Monaghan. There are also several pages of single paragraph reviews of various magickal books, featuring the output of everyone from Scarlet Imprint to Llewellyn.

The Cauldron is available for a four issue subscription and comes thoroughly recommended. UK annual subscription: UK £15.00, Europe €30, USA US$50, Canada Can$50, Australia Aus$50, New Zealand: NZ$60.