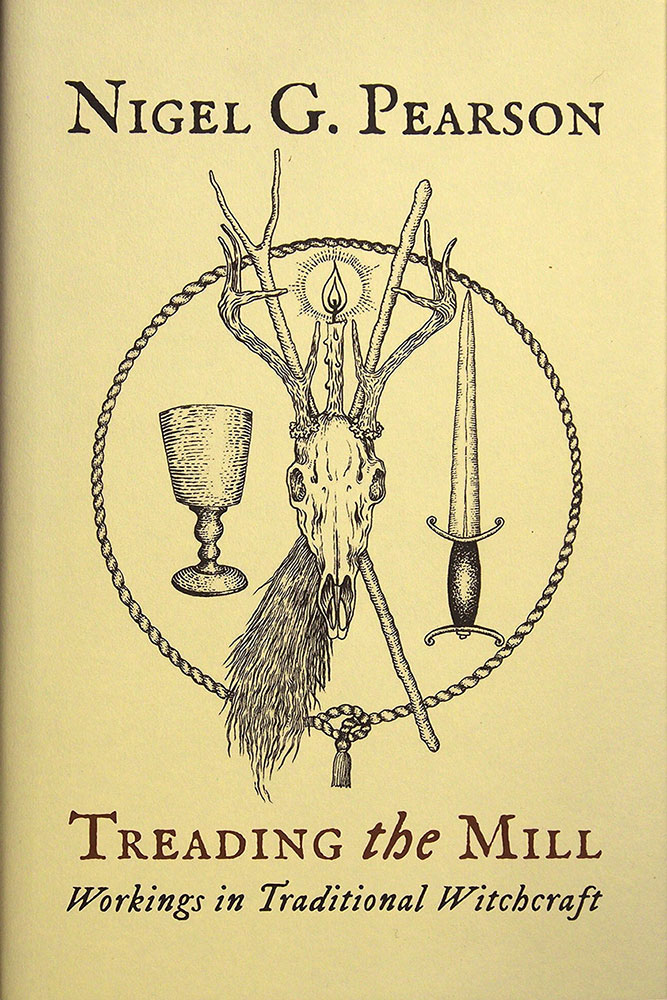

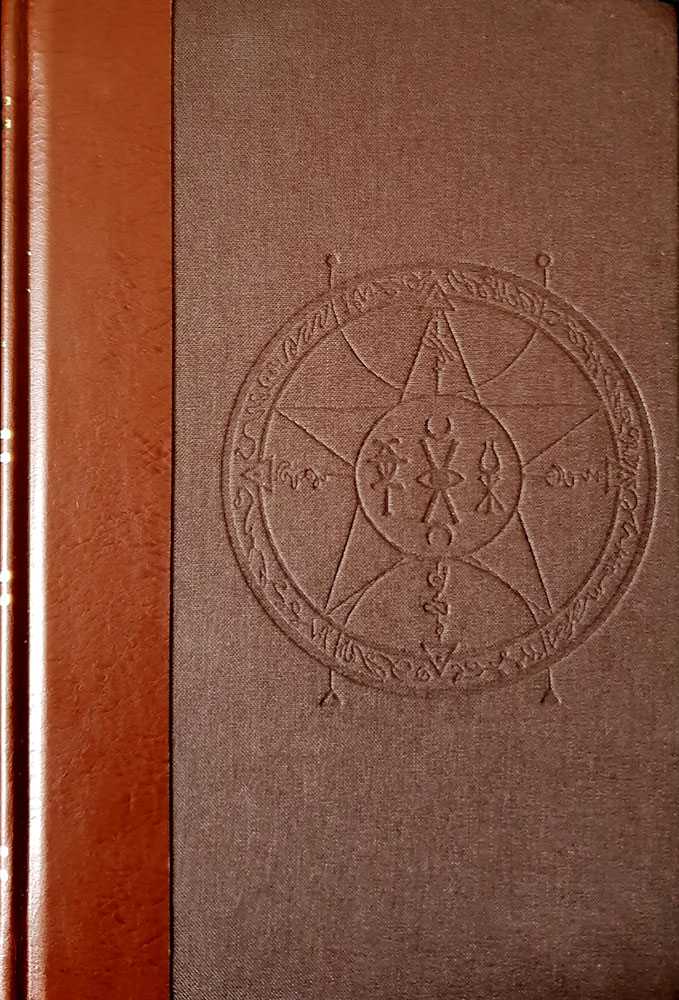

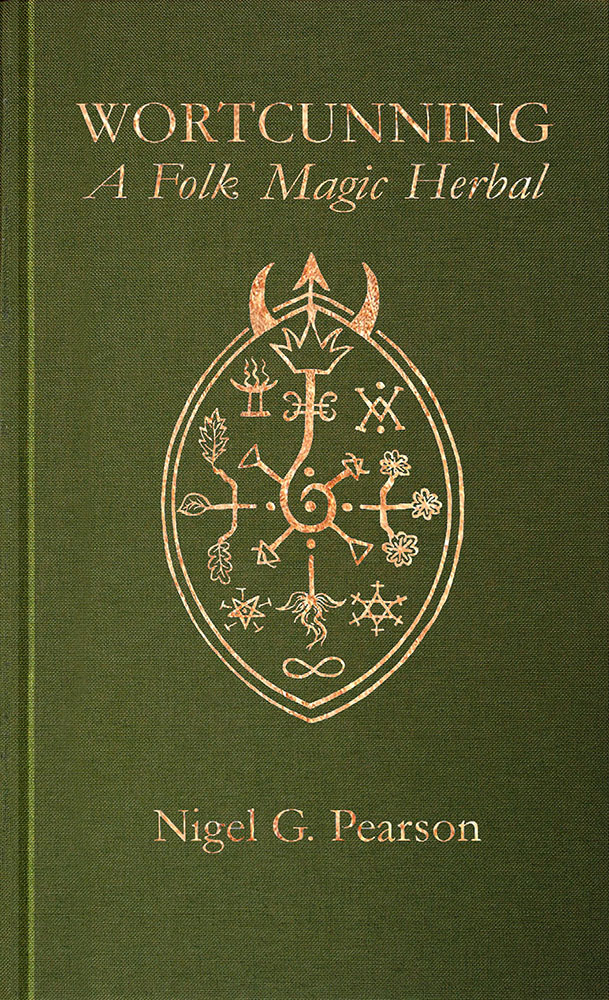

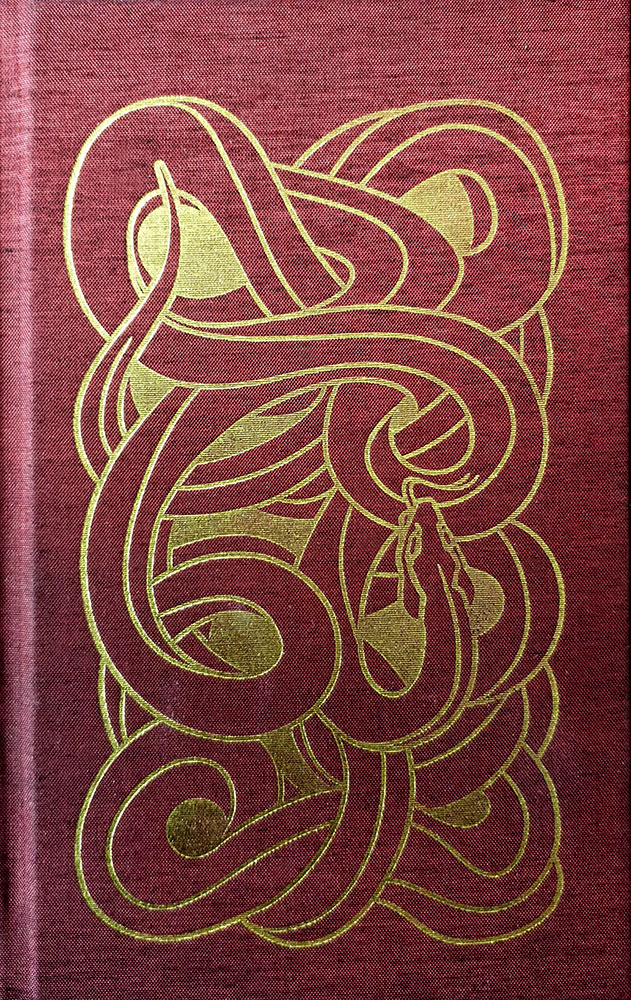

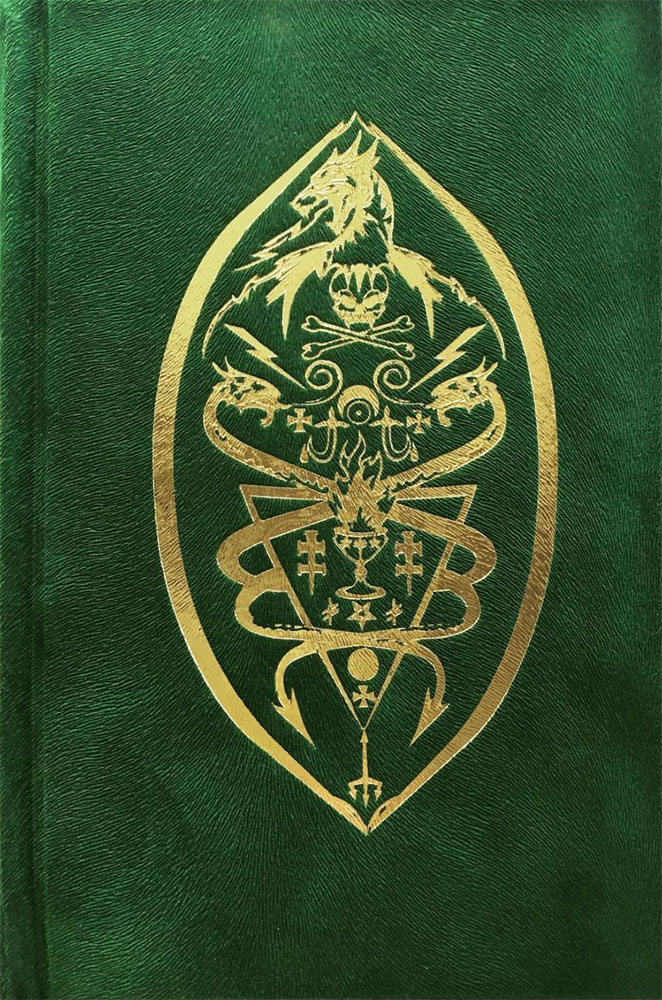

Originally published in 2010 by Ixaxaar, Mark Alan Smith’s Queen of Hell is here released as a Nightside edition via his own Primal Craft imprint, acting as the first instalment in a reissue of his Trident of Witchcraft trilogy. On the most immediate level, Queen of Hell looks like everything you want in an occult publication: bound in a luxurious green velvet cloth, sigils on the front and reverse covers foiled in gold, blackletter title on the spine (also in gold, naturally), and said spine with a substantial, tome-worthy width of three centimetres. Plus, a matching green cloth bookmark, huzzah!

Originally published in 2010 by Ixaxaar, Mark Alan Smith’s Queen of Hell is here released as a Nightside edition via his own Primal Craft imprint, acting as the first instalment in a reissue of his Trident of Witchcraft trilogy. On the most immediate level, Queen of Hell looks like everything you want in an occult publication: bound in a luxurious green velvet cloth, sigils on the front and reverse covers foiled in gold, blackletter title on the spine (also in gold, naturally), and said spine with a substantial, tome-worthy width of three centimetres. Plus, a matching green cloth bookmark, huzzah!

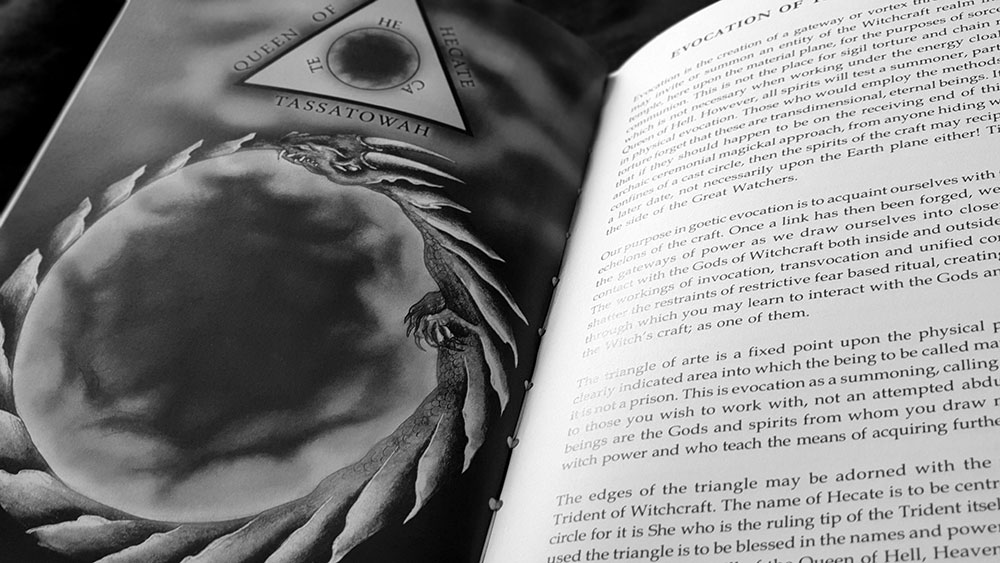

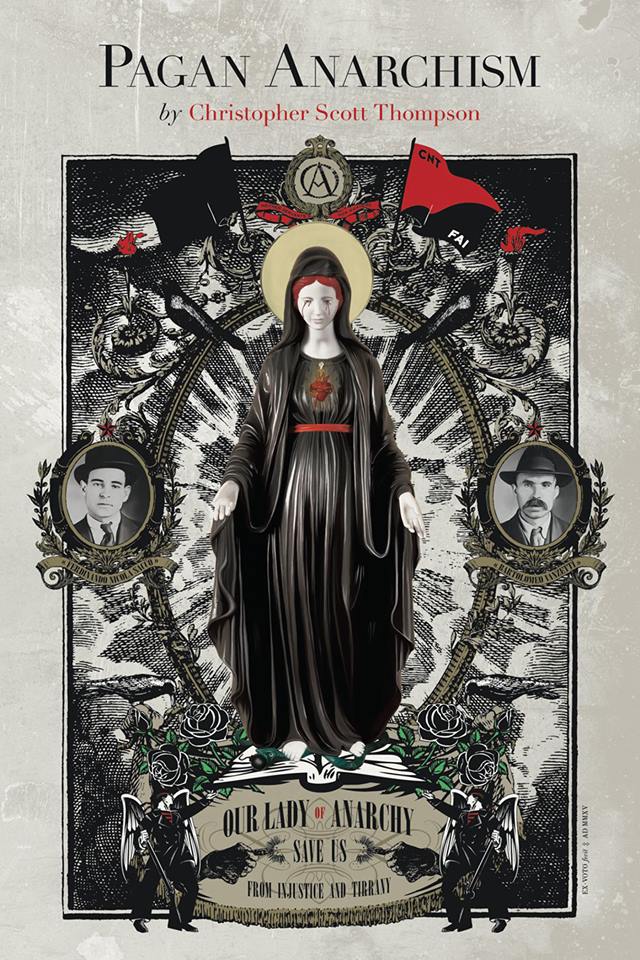

The queen of hell of the title is Hekate (henceforth Hecate, in deference to Smith’s spelling) but the Hecate within these pages bears only a passing resemblance to the goddess of classical Greek and Roman sources, and appears, instead, as the figure of the book’s title, a diabolical queen of hell and witchcraft of the most glamorously demonic kind. Largely unmoored from her classical origins, Hecate here instead exists within a more qliphothic cosmology and goetic pantheon; something that is made clear from the first page of the first chapter where her throne is said to be beyond Kether and its corresponding qliphah Thaumiel, and with her envisioned as a primordial first goddess, the highest tip of the initiating power or trident of witchcraft, and the queen not only of hell but of heaven and earth. While this has little parallel with the traditional image of Hecate, it must be said that divorced from the specific nomenclature of the qliphoth, it does recall her appearance in the Chaldean Oracles in which she is a grand cosmic force, the lightning-receiving womb and formless fire of the aneidon pur, visible throughout the cosmos.

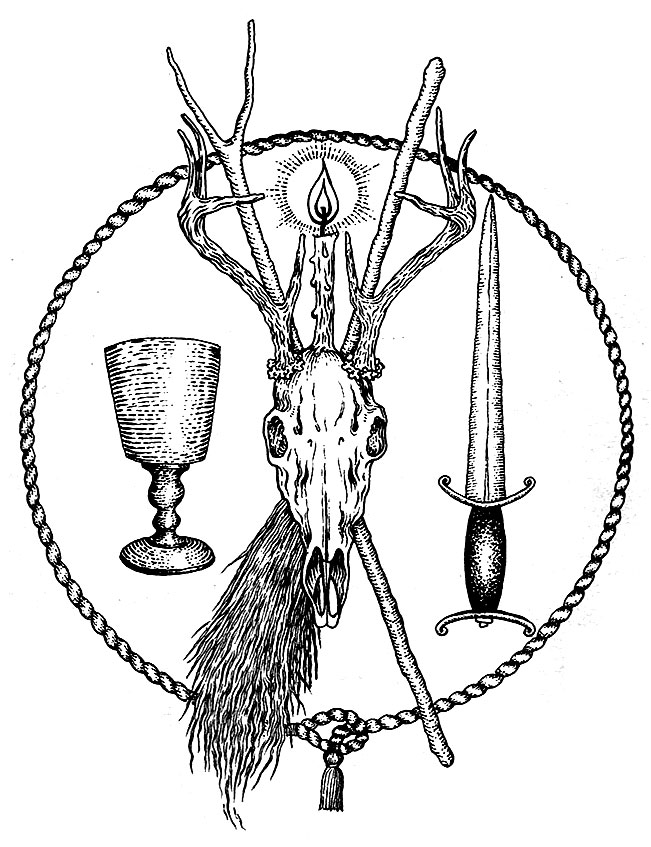

Despite the qliphothic decoration, it is fundamentally a form of witchcraft that is presented here, made none more clearer than in the next chapter and its listing of some familiar ritual implements: athame, wand, chalice, pentacle, sword, salt, etc. Smith gives his own dark veneer of interpretation to these, though, with the wand as the staff of the Dark Lord, the chalice as the grail that is the emerald of Lucifer fallen from on high, and multiple references to Atlantis, which in Smith’s cosmology acts as an ur-culture for his pantheon and its tradition.

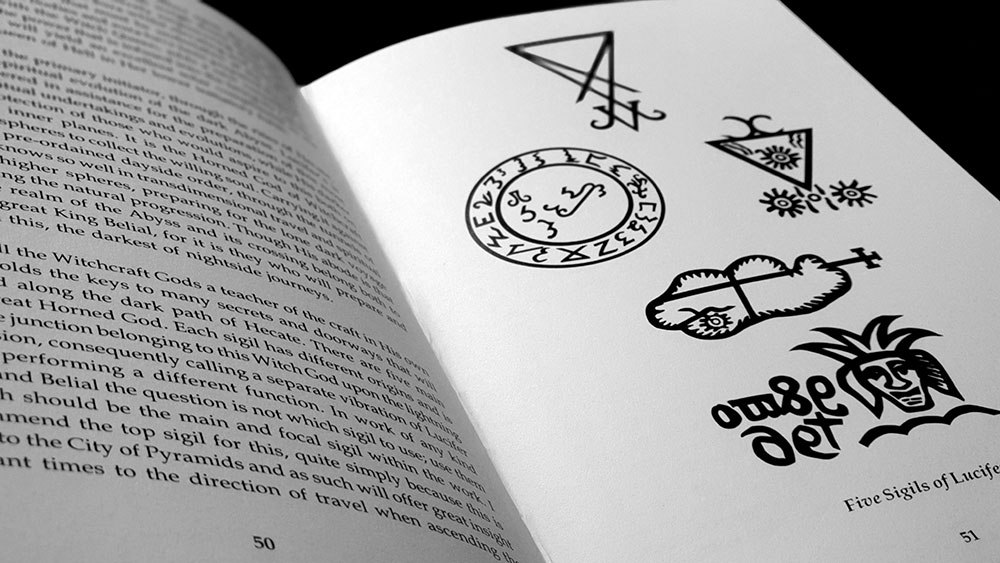

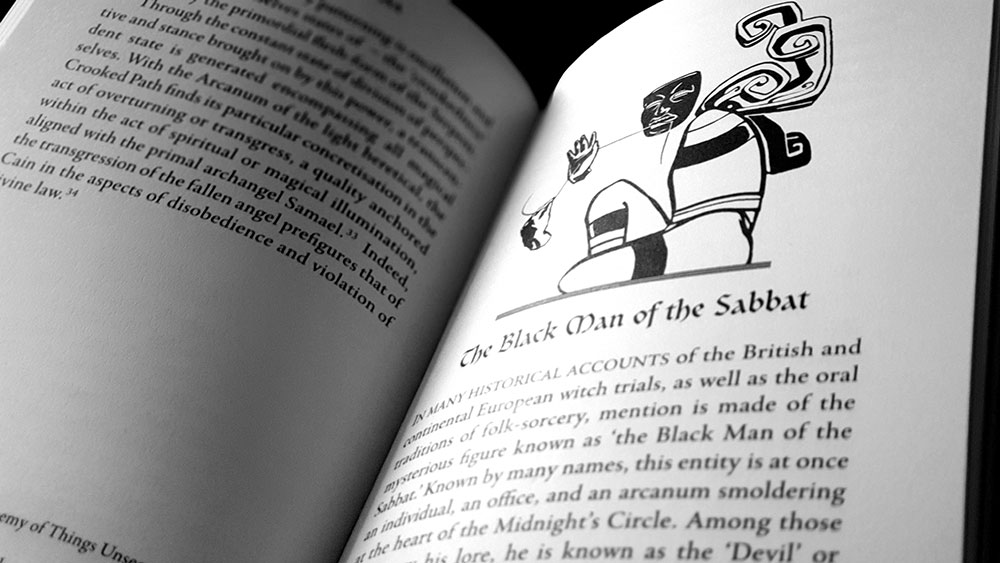

This demonic side comes to the fore fairly on when Smith provides an overview of his core pantheon, headed, naturally, by Hecate and followed by the two other points of this Trident of Witchcraft: Lucifer and Belial (subjects of their own books in this trilogy as the titular Red King and Crown Prince of the Sabbat respectively). Somewhat reminiscent of the legend of Diana and Aradia as recorded by Charles Leland, Lucifer is defined as the son and brother of Hecate, a dark solar form of the horned god of witchcraft. Belial, meanwhile, is conflated with Beelzebub and identified as the ruler of the qliphah Ghagiel and as a darker twin of Lucifer, thereby being described by Hecate as “the spawn of my spawn.” Rather than create new sigils for Lucifer and Belial in an already crowded sigil market, Smith relies on the classics and draws from grimoires. And instead of picking just one sigil, he presents the various variations from the Grand Grimoire, the Grimorium Verum, and the Lemegeton. Each is said to be a separate junction belonging to its spirit, though some are given more significance than others, such as, for example, the familiar and more aesthetically-pleasing Grimoirium Verum sigil for Lucifer, which, as its form suggests, is said to be the gateway to the City of Pyramids.

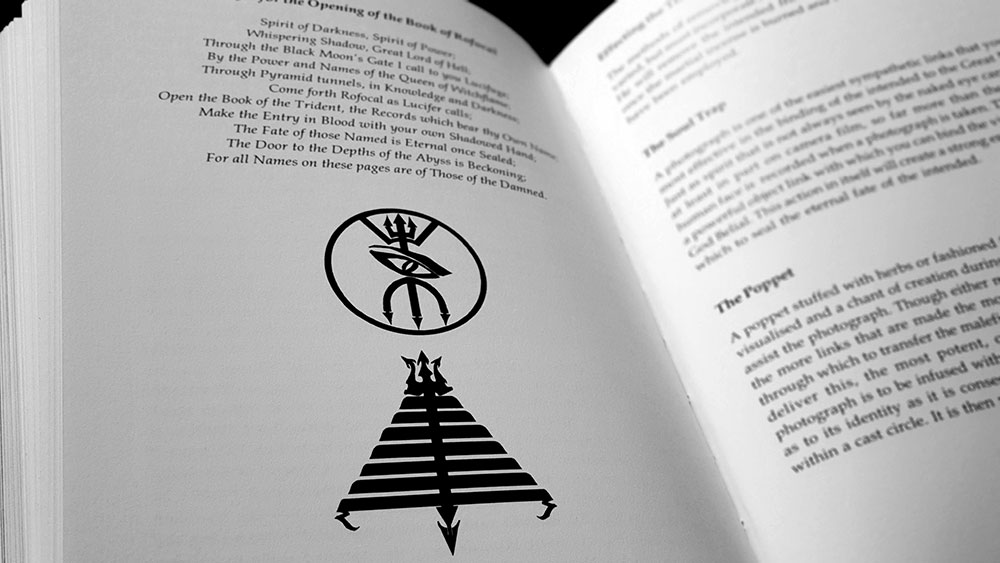

Beyond this primary trinity of powers, Smith list a range of lesser spirits, once again mixing demonology with the occasional nod to Greek mythology. Thus, sitting quite happily alongside goetic spirits like Surgat and Lucifuge Rofocal are the fate-spinning trio of the Moirai, the Hadean daimon Eurynomos, and the hound Cerberus. Like Hecate (their sister in this telling), the three Moirai, Clotho, Lachesis and Atropos, are contextualised within a qliphothic framework, and given an abode in the qliphah of Sathariel from which they also access Gamaliel for works of dark moon magick. Similarly, Eurynomos dwells in Belial’s qliphah of Ghagiel, while Cerberus is associated with Daath and the initiatory great Abyss.

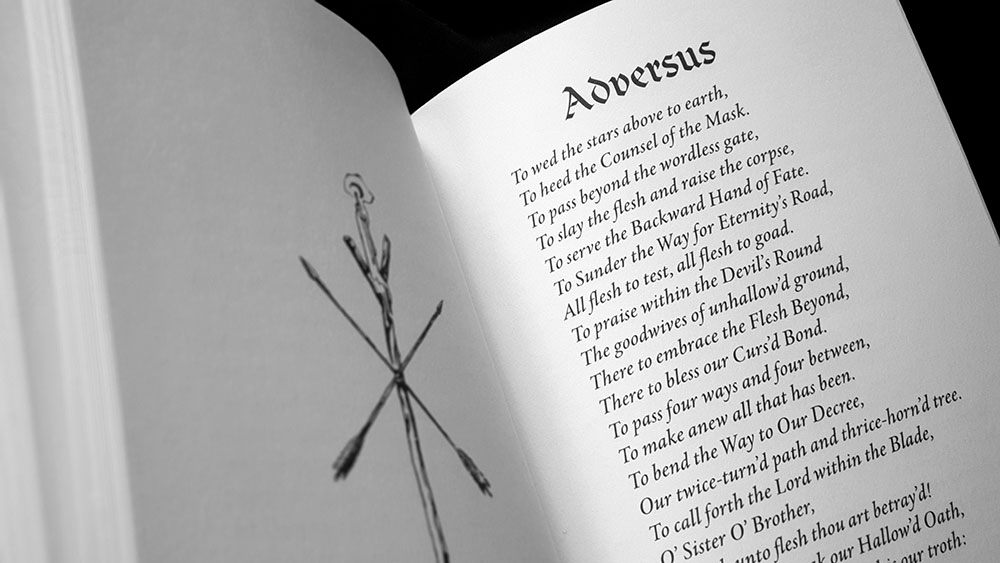

As the cast of characters and their areas of influence attest, there is, unsurprisingly, a distinctively dark hue to the content of Queen of Hell, with everything cast within a grimly glamorous aesthetic of moons and serpents, horns and blood, stars and fire. The language of the rites and evocations echoes this, employing a rich, descriptive lexicon in service of a suitably gothic liturgy. It’s not entirely tenebrous, though, and Smith embraces Hecate’s role as queen of heaven as much of hell by having one invocation of a force from the Empyrean realm, with the Archangel Michael called upon as an initiatory force, ultimately merging with Lucifer within the practitioner, the two acting effectively as classic shoulder angels and devils.

Smith writes with a style that is no-nonsense with little room for handholding, deferring to no authority other than that of his own tradition. In some cases, it seems to be assumed that you have gleamed all that needs to be gleamed in the discussion of a particular technique, often presented in its core theory rather than step-by-step instructions, and then you’re on your own if you weren’t paying attention. There’s nothing wrong with such an approach, as it ensures focus and emphasises the experiential, with each incremental step building one ‘pon t’other.

Summoning in a broadly goetic style plays a large part in the magical arsenal here (with some major tweaks, as one would expect, with less of the cajoling and threatening), with all of the previously mentioned cast, as well as a broad range of other beings, having invocations. But there are also little things that bring this primal craft back to its witchy underpinnings. There’s a discussion of core techniques of malefica, the use of familiars, a brief diversion into the now almost de rigueur toad rite, as well as the employment of totemic witch bottles (here called spirit pots) to house egregores, and in a continuation of the theme but on a larger scale, the use of cauldrons as a gateway between worlds.

Queen of Hell concludes with a second part, defined as its own self-contained Book of the Inner Sanctum (though the first part of the book is not given a comparable heading), in which the focus moves away from the practical sorcery of the first half and into the astral. The Inner Sanctum of the title encompasses the highest powers and gnosis in the Primal Craft system, and these are accessed with a series of considerably and increasingly more complex and involved rituals, incorporating a variation of the aforementioned toad bone rite, as well as a series of other workings that have less of a familiar witchy pedigree. It is this section which underpins the general impression generated by Queen of Hell, in that what is presented here is a complex, thorough system that, should it and its aesthetics appeal to you, has a lot to work with.

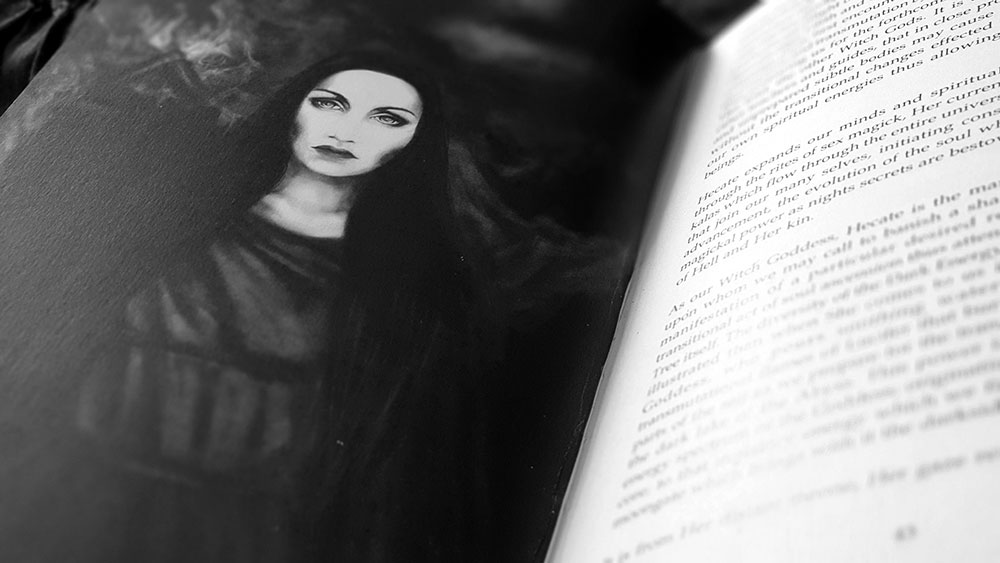

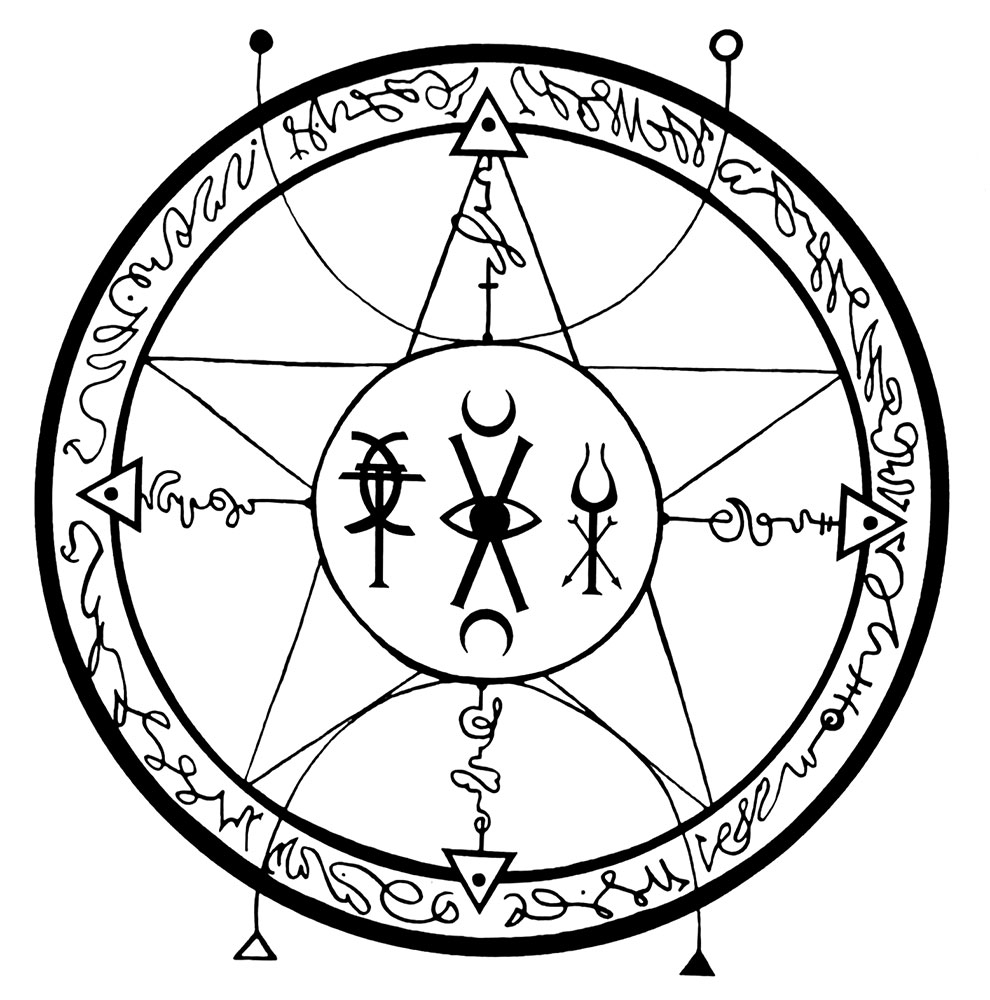

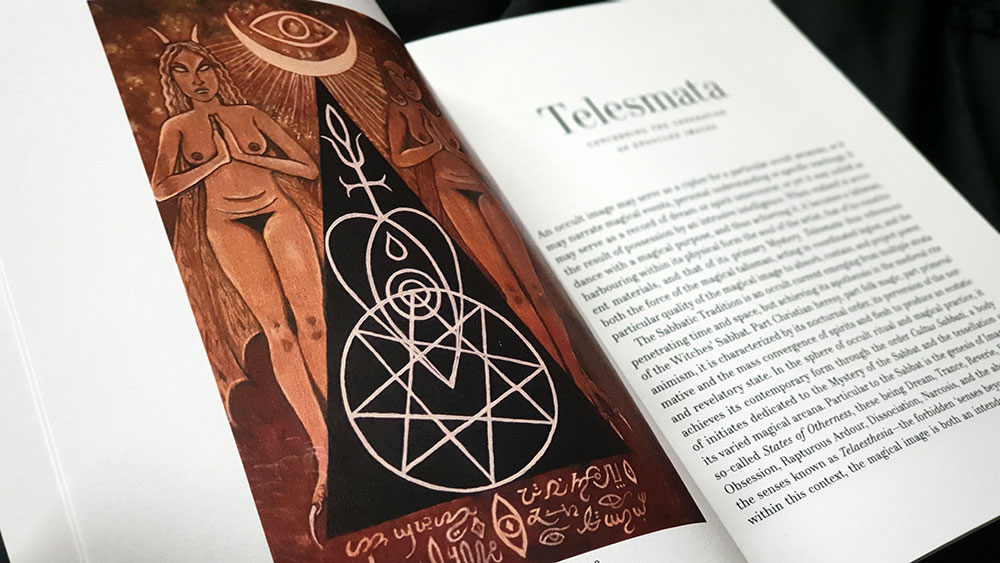

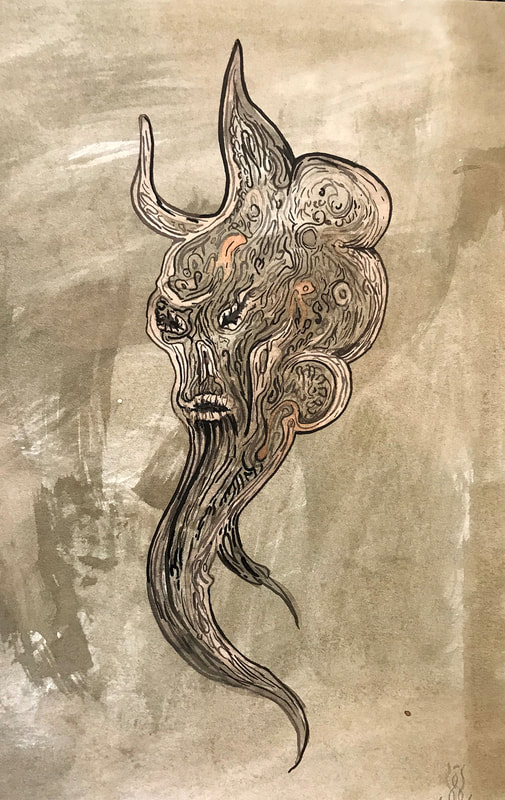

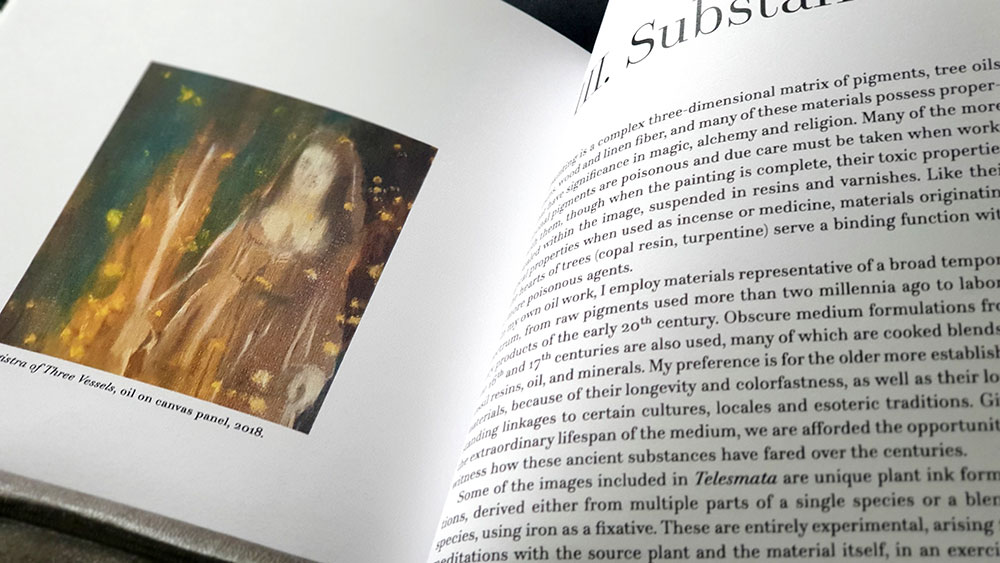

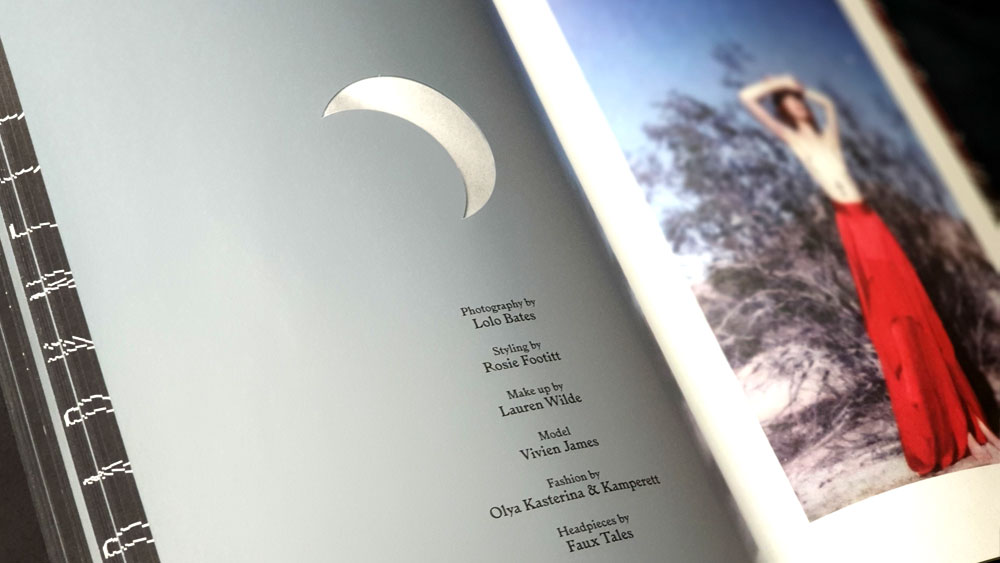

Queen of Hell is illustrated in a style similar to all Primal Craft titles, with sigils rendered as chunky, somewhat-angular, heavy-weighted vector forms, while illustrations are full page glossy plates that have some hand-drawn elements but are also heavy on post-processing, with blurred Photoshop-rendered flames, smoke and clouds. The most striking of these is a portrait of Hecate in which she eerily resembles Carice van Houten as the Lady Melisandre from Game of Thrones, with the ruins of some building ablaze in the background.

Typesetting in Queen of Hell is rather utilitarian, with the body in a slightly too large serif face, with subtitles in a bold variation of the same, and chapter titles all-caps in another serif face, Garamond. This is set as fully-justified paragraphs, within conservative left, right and top margins, creating a somewhat cramped feeling. Paper stock is heavier than usual, sitting between 130 and 140 gsm, and having an almost card-like quality, which may account for a few places where the binding seems to have suffered.

This Nightside edition of Queen of Hell was released in a now sold-out edition of 500, featuring double thickness endpapers, and handbound in an emerald Lynel Fur that retains the green of the Ixaxaar edition, but with a new sigil foiled in gold on the cover. Sigils within and other artwork have been recreated and enhanced, the promotional blurb tells us, by the D’via Roja Group (though both context and even the powers of Google make it hard to tell who or what this group are).

Published by Primal Craft