This is the second book by A. D. Mercer to be reviewed here at Scriptus Recensera, and he marks himself as a bit of the old polymath with this title, bearing little relation to the Enochian milieu of the past review, or the as yet unread survey of Armanen runes. Bearing the subtitle “Charms, Spells & Witchcraft of Old Britain,” it also has the faux archaic and comma-addled sub-subtitle “A gathering of historical enchantments against Foul Spirits & Maledictions. Compil’d, & with an introduction by A. D. Mercer.”

This is the second book by A. D. Mercer to be reviewed here at Scriptus Recensera, and he marks himself as a bit of the old polymath with this title, bearing little relation to the Enochian milieu of the past review, or the as yet unread survey of Armanen runes. Bearing the subtitle “Charms, Spells & Witchcraft of Old Britain,” it also has the faux archaic and comma-addled sub-subtitle “A gathering of historical enchantments against Foul Spirits & Maledictions. Compil’d, & with an introduction by A. D. Mercer.”

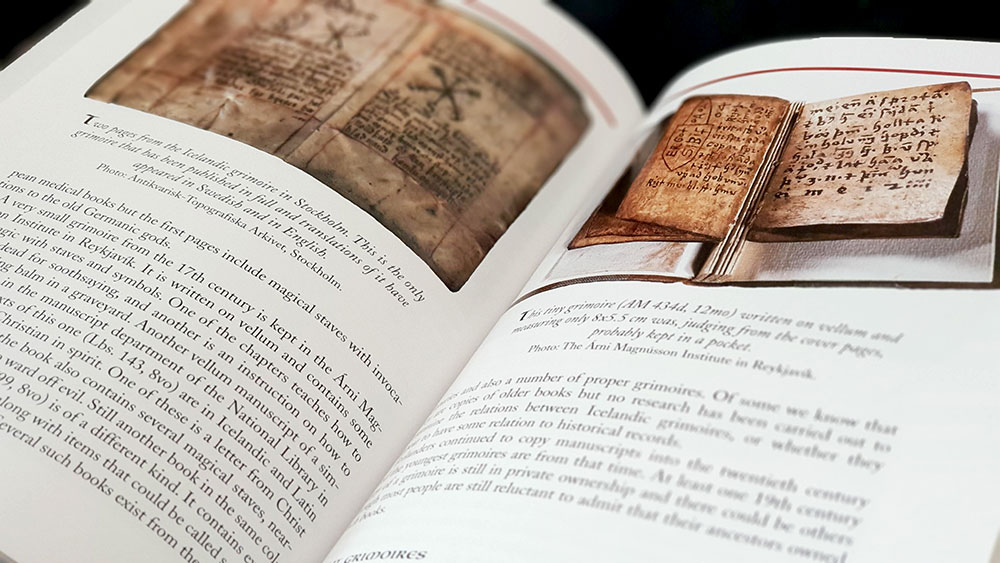

In said introduction, Mercer mentions the black books of Scandinavia that contain folk magic cures and charms, and laments the lack of extant British equivalents; despite there being tantalising titles for such lost tomes like The Devil’s Plantation and The Red Book of Appin. The Wicked Shall Decay seeks to rectify this by bringing together the kind of spells, charms and incantations that might have been in such a book, drawing on a variety of publications on British folklore from the nineteenth and twentieth century.

The spells and charms are grouped together into broad categories such as the healing of wounds, protection and defence, and dealing variously with witches, the devil and ghosts. In addition to simple spoken charms and formulas of sympathetic magic, there are some examples of sigil and magic square work that draws from the grimoire tradition. Each entry is preceded by a title (with inconsistent capitalisation and punctuation) and each ends, by way of reference, with a bracketed three letter code indicating the source text, and a number pointing to, one hopes, the particular page on which it appears. There are some 36 publications in the bibliography, making for a wide pool of resources to draw from; though some feature more heavily than others. Mercer points out that he avoided Reginald Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft or direct trial records, finding the former too obvious, while in the latter, he argues, any spells or charms may have just been made up by prosecutors for the charge sheet.

When it comes to longer sections in his own words, the problems with Mercer’s writing, noted in the review of his Liber Coronzom, recur, and are cruelly abetted with insufficient proofing by Three Hands Press. He writes in a cumbersome, extended manner, producing sentences that run on, losing their tense in the breathless length. The writing is flabby and tautological, redundancies abound, and words are reused within sentences when a synonym would be tidier. Proofing is so careless that George Ewart Evans, for example, can be called Evans and Even in the same paragraph; with an improper use of a possessive apostrophe too for good measure.

Given this, the reader may be filled with a little dread when Mercer says in his introduction that while he has, for the most part, retained the spelling and grammar of entries for the sake of authenticity, in some he has modernised them to aid understanding. Perversely, this attempt at aiding understanding sometimes seems to replace the original writers’ proper placement of commas with Mercer’s misunderstanding of punctuation, in which he infuriatingly uses them to mark the beginning of interrupting words and expressions, but not the end. Due to the prevalence of persistently poor punctuation, the reader finds themselves on guard for other errors in the transcription, and these crop up more often than they should, with words missing from sentences, whole phrases introduced that weren’t in the original, and formatting errors like accidental paragraph returns or individual lines that are combined into one without adjusting the sentence case. Without a thorough review of all entries it would be disingenuous to say that this sort of thing is true of all the content, but the cross-referencing of just a few examples throws up problems. One finds oneself descending down rabbit holes of fact checking, when one little thing looks wrong, only to find that yes, this has been transcribed wrong, yes, that little bit of Latin didn’t ring true because they’ve lazily mistaken an ‘e’ for a ‘c,’ and yes, that author’s name was Oliver Madox Hueffer, not Olivier Maddox Hueffer.

The same is true of general accuracy in citation. In at least one case, the three letter reference code points to a publication that is not given that or any code in the bibliography (possibly because Mercer subsequently assigned separate codes to the book’s two volumes and didn’t update the body), while in another, the spell bears a code for a book that, despite having those three letters, doesn’t appear in the bibliography at all. Then there’s at least one instance in which the example doesn’t appear in the referenced publication, neither on the cited page or, it would seem, on any of its pages (and just for fun, ‘may’ is misspelt ‘many’ in this entry too), while in others, the reference is there, but on a different page; 87 instead of 67, for example. Finding some references in their sources can create even more consternation, such as several that are referenced from Oliver Madox Hueffer’s The Book of Witches. Here, Madox Hueffer is actually quoting Johann Weyer and in neither Madox Hueffer’s book, or in Weyer’s original is there any indication that what is being recorded is a charm from Britain; nor does Reginald Scot referencing Weyer in his The Discoverie of Witchcraft make them any more British.

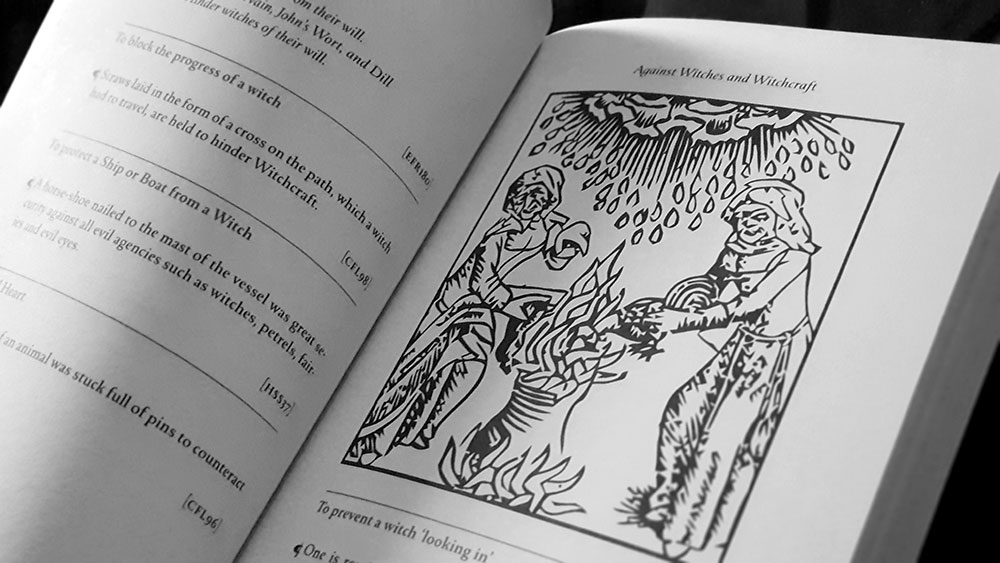

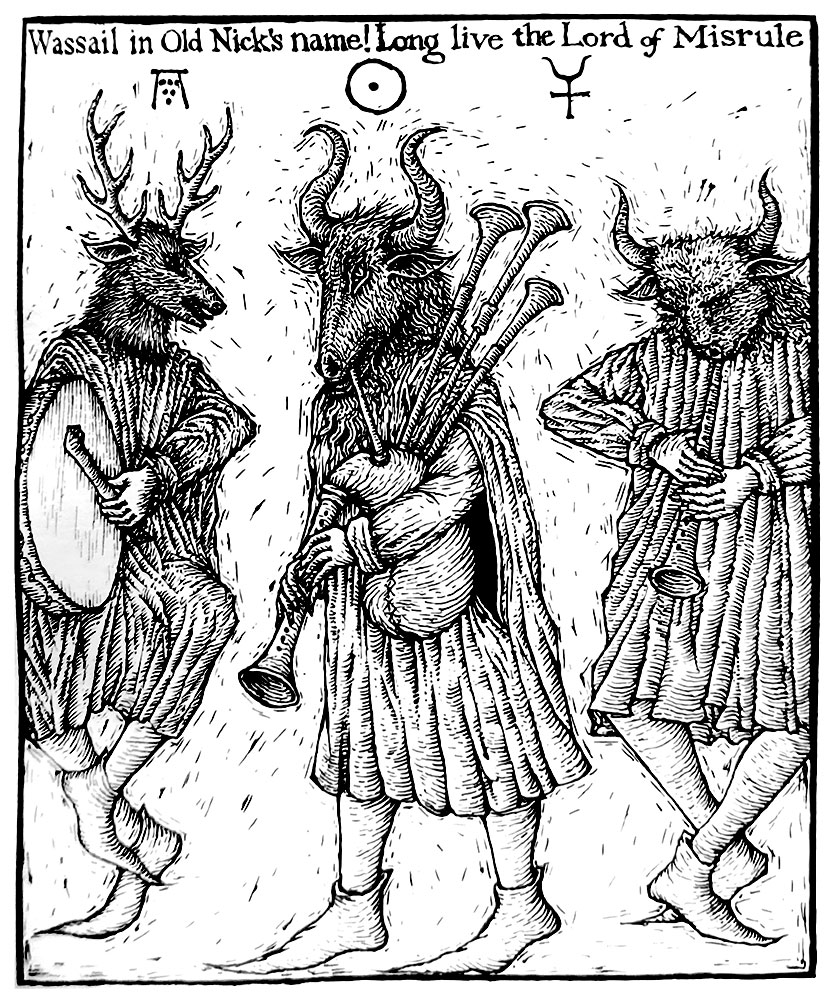

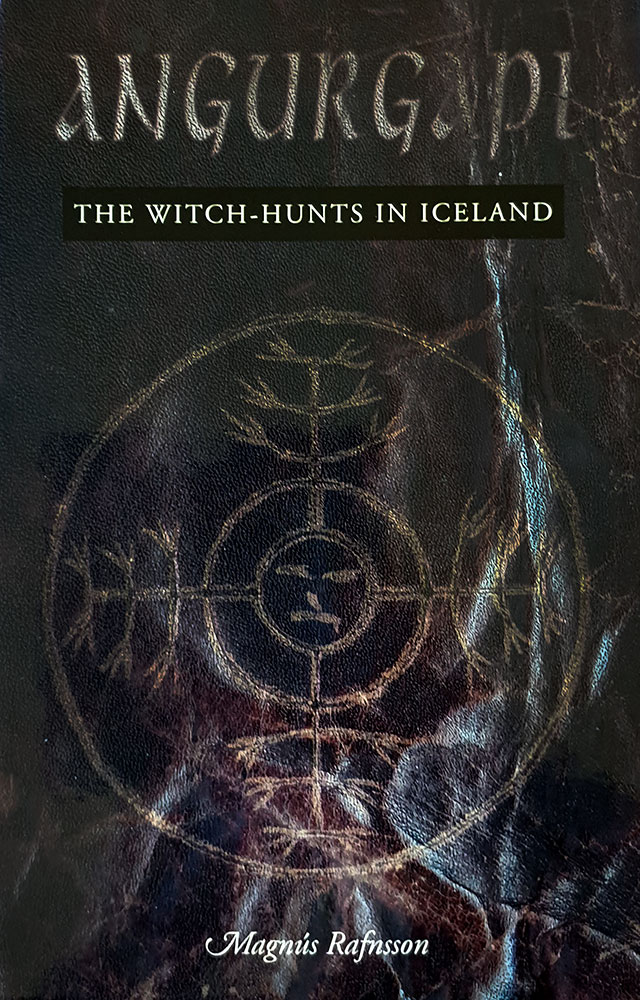

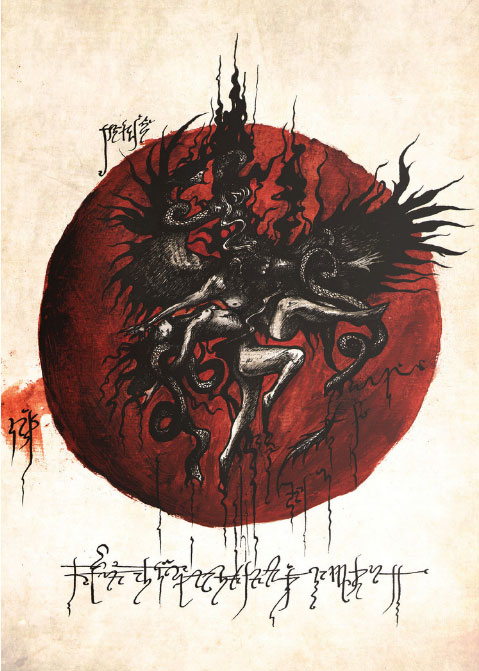

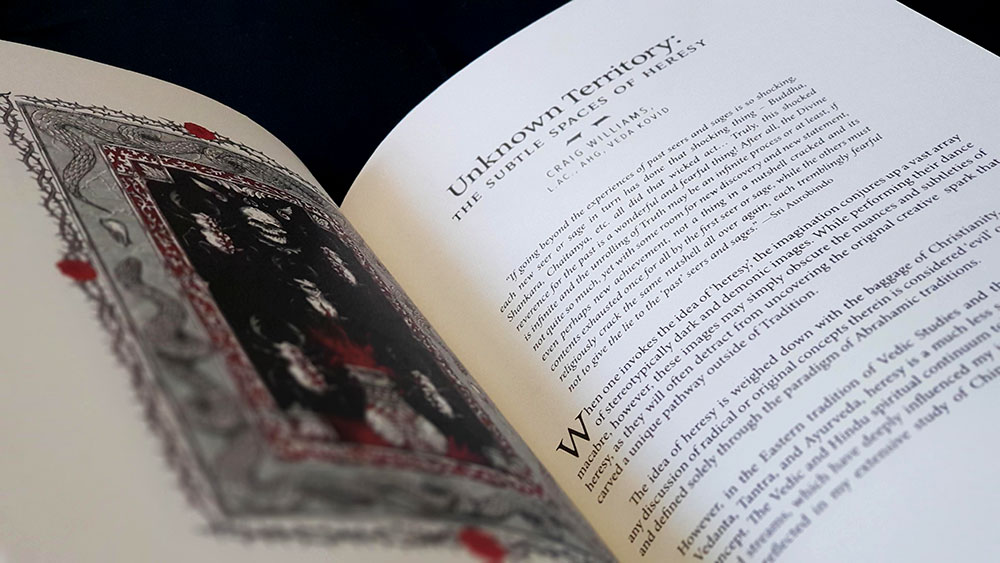

The 168 pages of The Wicked Shall Decay are printed in a two colour offset on heavy stock, with titles, subtitles, dropcaps and dividers in a lovely muted red and the body in black. It is illustrated throughout with what the promotional blurb generously describes as 31 woodcut illustrations. Some of the images may have begun life as woodcuts but most if not all have been automatically vectorised in a programme like Adobe Illustrator and the source material in many cases obviously wasn’t high enough quality to warrant it. Some are particularly bad and have no place being in print, such as a the above derivation of Two Witches Cooking up a Storm (the titlepage from Ulrich Molitor’s 1489 De Lamiis et Pythonicis Mulieribus) which is here rendered almost into abstract oblivion, the faces and bodies of the witches disintegrating into clumsy, laughable facets. And then there’s something which one assumes is a tree on page 92, or the brittle, piecemeal Rod of Asclepius on page 147, or two equally bad traces of an Abracadabra hexagram, which could have been effortlessly recreated from scratch by anyone worth their salt. As it is, there’s little case for using many of these images as their selection and placement is often arbitrary; and even in a case where it’s kind of apropos, why the Eye of Providence in a section on the Evil Eye? Also, the style, depending on the quality and provenance of the source image, varies widely, with weight and quality of trace inconsistent throughout.

The Wicked Shall Decay is interesting as what is effectively a reference list. It provides a glimpse of a variety of spells and charms, but given the sloppy transcription and referencing you would never want to trust it without going back to the source. If nothing else, The Wicked Shall Decay gave this reviewer the opportunity to spend perhaps far too many hours looking through the very texts from which it draws.

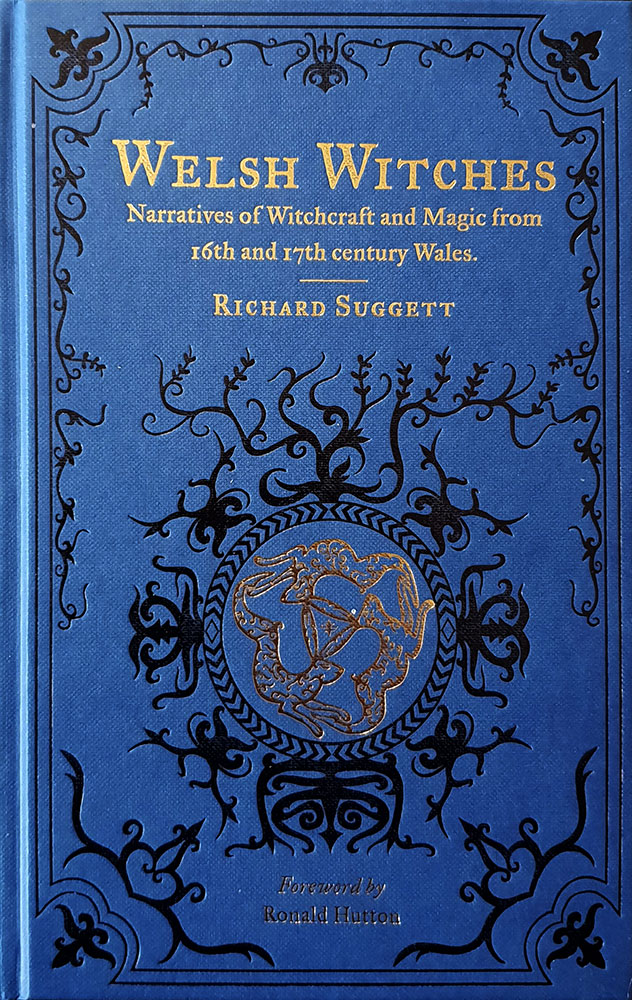

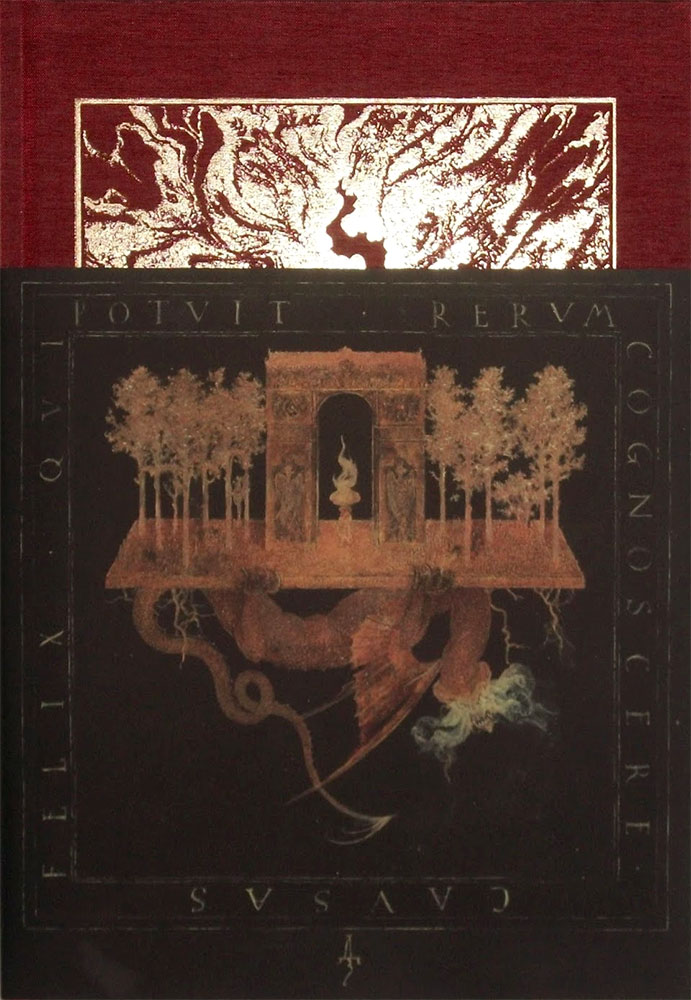

The Wicked Shall Decay is available in three editions with a trade paperback, a standard hardcover in carmine cloth with two-colour embossed wraps, and a deluxe edition of 44 copies in full earthen full goatskin, with marbled endpapers and slipcase, bound by The Key Printing and Binding of Oakland.

Published by Three Hands Press.