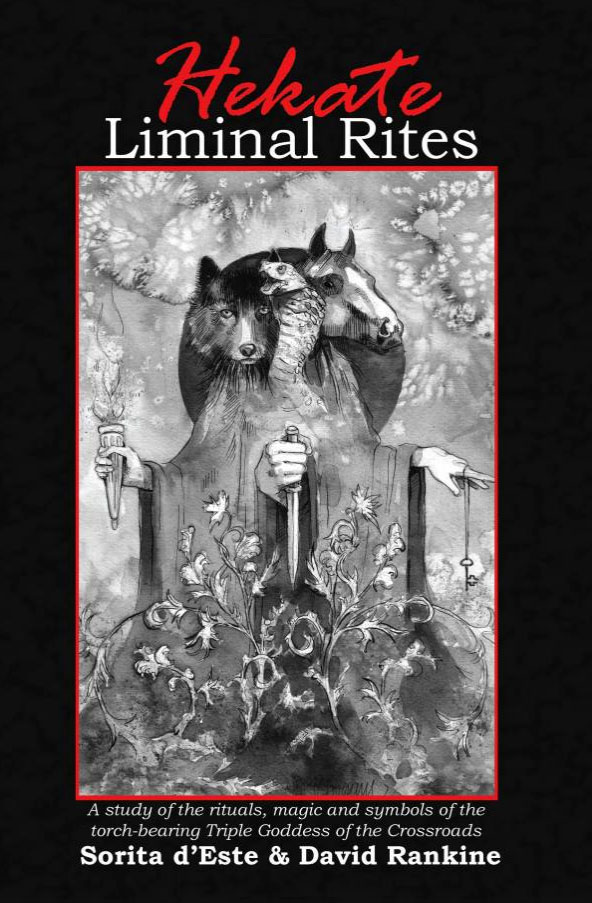

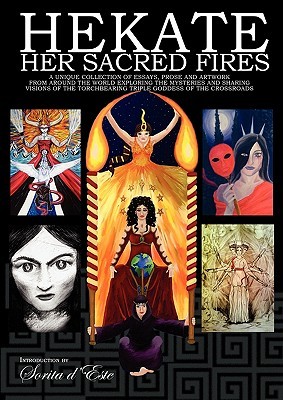

Apparently some unwritten goal here at Scriptus Recensera is to review all recently published titles related to Hekate, so much so that she’s the only deity here with her own subject tag. This might be a somewhat insurmountable task, given her popularity at Avalonia alone, with this being but one of two anthologies released by that press in honour of her; the other being the equally colon-deficient Hekate Key to the Crossroads from 2006. Published in 2010, this massive work takes a more global view than its predecessor and brings together contributions from more than fifty people, with some familiar names but considerably more who just appear to be practitioners who are not otherwise writers. This vast cast is somewhat intimated in the cover which has not a single image but many, featuring the work of Emily Carding, Brian Andrews, Shay Skepevski, Georgi Mishev, and in the centre, Magin Rose.

Apparently some unwritten goal here at Scriptus Recensera is to review all recently published titles related to Hekate, so much so that she’s the only deity here with her own subject tag. This might be a somewhat insurmountable task, given her popularity at Avalonia alone, with this being but one of two anthologies released by that press in honour of her; the other being the equally colon-deficient Hekate Key to the Crossroads from 2006. Published in 2010, this massive work takes a more global view than its predecessor and brings together contributions from more than fifty people, with some familiar names but considerably more who just appear to be practitioners who are not otherwise writers. This vast cast is somewhat intimated in the cover which has not a single image but many, featuring the work of Emily Carding, Brian Andrews, Shay Skepevski, Georgi Mishev, and in the centre, Magin Rose.

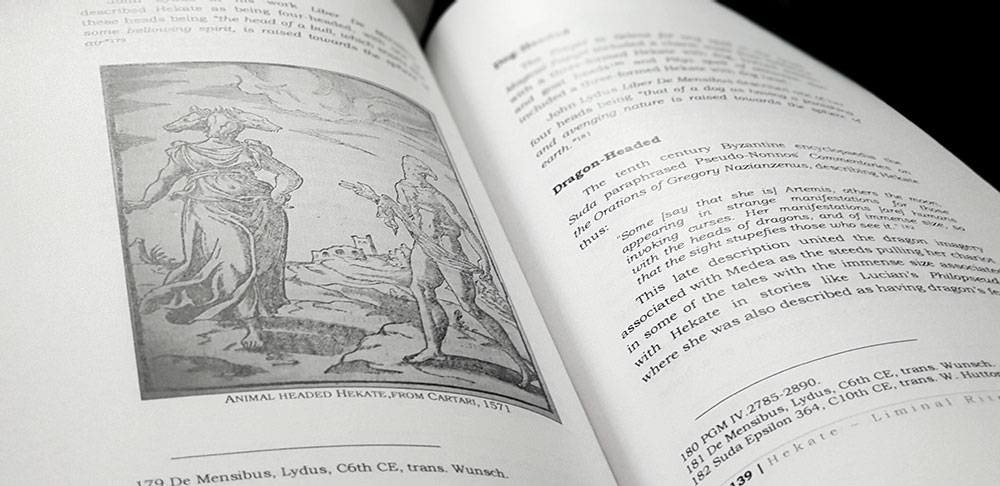

Hekate Her Sacred Fires is presented as a large format A4 book, which doesn’t make for the most pleasant reading experience. Reading on-the-go is pretty much out of the question, and reading not-on-the-go isn’t all that easy either, with the ungainly format requiring a solid reading surface lest hand fatigue and RSI kick in. In addition to the physical aspects, the large dimensions don’t allow for the most sympathetic of layouts. Text is formatted in a single, page-wide column, meaning that the enervation of hands and limbs is joined by a similar weariness of eyes and concentration, with the excessive line-length being detrimental to sustained comprehension. The formatting of the text doesn’t help in this manner either, providing little in the way of visual interest. Paragraphs are fully-justified, and separated with a line-space between, but they also have redundant and far-too-large first line idents, including the first paragraph and in one infuriating instance, subtitles; meaning that the body text can appear insubstantial and untethered. Titles and subtitles are presented as larger and bolded versions of the body typeface, set in the almost-a-slab-serif face that Avalonia have stuck with over the years. There are images preceding almost every contribution on the verso side of the page spreads but these, like the various other illustrations and photographs that fill spaces throughout the book, are of varying quality and are not treated that well by Lightning Source’s print-on-demand press.

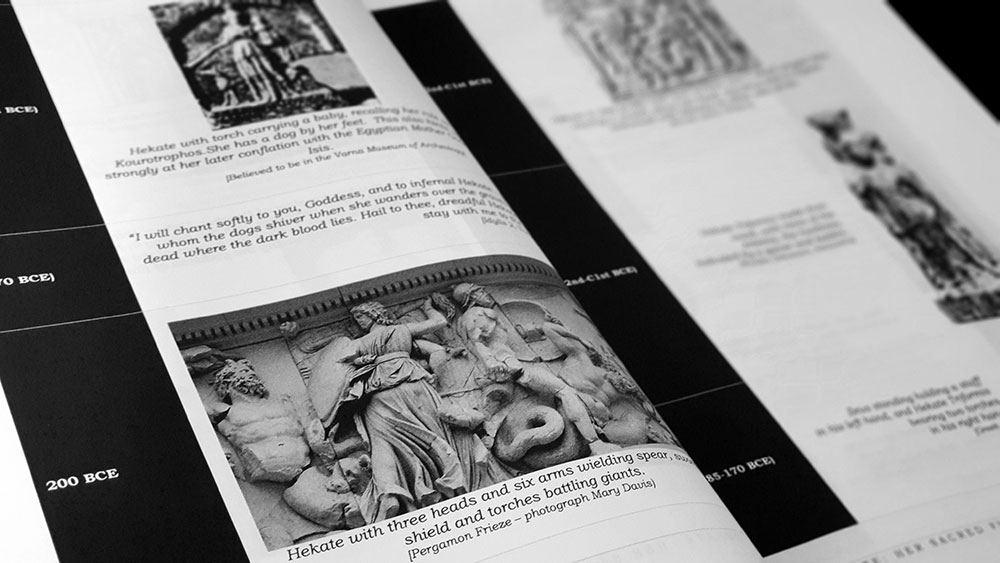

This all means that it can be hard to get into Hekate Her Sacred Fires, and it is a testament to this difficulty that this review has sat here half-written for some time. Once one does make it past the monstrously large pages and the walls of long-line-length text, a sense of the variety in contributions begins to emerge, though the majority are first-hand accounts of working with Hekate. But first off, in her own introductory section, is d’Este, who gives an overview of Hekate, providing a thorough historical grounding that allows for the more speculative or specialised considerations that come later. This is then followed by an exhaustive illustrated timeline that is spread across nineteen pages, and stretches from 6000 BCE, with the beginning of the Neolithic period, right up to 2000 CE where it concludes with the publication of d’Este’s book Hekate Key to the Crossroads.

With over fifty contributors there is a demonstrable diversity in what is presented here, all of varying approaches, styles and quality, in both matters magical and literary. It is the personal that dominates throughout, beginning with Georgi Mishev who gives a personal biography and testimonial of his Bulgarian approach to goddess spirituality in general and Hekate in particular, as does compatriot Ekaterina Ilieva in the following piece. Similarly, Shani Oates provides a record of a ritual for Hekate from several years prior with results of great profundity; prefaced with an introduction of equally great and characteristic verbosity. Some of these contributions include a practical element with the personal, such as John Canard who talks about using meteor showers for spell work, or Amelia Ounsted who maps out the whole Wiccan year of festivities with ways in which they can be related back to Hekate.

Some of the more interesting contributions here move beyond the respectable and reputable classical world of Hekate, as necessary and worthy as that grounding may be, and into the more darkly glamorous realms of sabbatic and Luciferian witchcraft. This comes most notably from the pen of Mark Alan Smith whose appearance amongst these other authors seems a little incongruous, but it is a theme also discussed first by Trystn M. Branwynn in the gloriously-titled The Hekatine Strain. Here, Branwynn discusses Hekate as but one of the names of the pale Queen of the Castle of Roses in Cochrane-style Traditional Witchcraft, drawing together a tapestry of threads from myth and folklore to unpack the symbols of Hekate, in particular the crossroads, and linking it ultimately back to this particular vision of witchcraft. Smith, in turn, writes, as one would expect, from the perspective of his Primal Craft tradition, telling of how Hekate introduced him to Lucifer who appears here as her consort. This is a thorough ritual account, documenting the long, distressing after effects of The Rite of the Phoenix, culminating in a crossing of the Abyss and a journey through the City of Pyramids.

The type of personal turmoil mentioned by Smith is not something unique to his contribution here, with several authors describing trauma and dark nights of the soul that either came through interacting with Hekate or were eventually soothed by her cathartic arrival. As always, there’s a variety of feelings and impressions that can be stirred up when reading such accounts, especially when it concerns mystical goings on and messages from the divine world; incredulity being one of them. But that is the nature of the brief here, so the reader needs to buckle in and enjoy the ride on this train of personal testimonies or get off at the next dour stop. For devotees of Hekate, though, one can imagine that a collection of so many allied voices would be well received and a valuable addition to one’s library.

In the end, it’s hard to get past the large formatting of Hekate Her Sacred Fires and it can be genuinely exhausting just to read a page, with your head and eyes having to travel right across each A4 width just to get one sentence in. It is obvious why this has been done, as with an existing page count of over 300, a volume with more conventional dimensions would have doubled the amount of pages to make for one hefty tome. One option might have been to reduce the number of submissions or to have at least pared down some of them in the edit, but there would probably have been some reluctance to do this, given that in her introduction, d’Este talks of how necessary it was to preserve the voice of so many writers; meaning that editing for proofing alone has been minimal, limited to what are designated essential changes.

Published by Avalonia