Subtitled Mythos, Ethos, Female & Priestly Mysteries of the Clan of Tubal Cain, this is a collection of articles by Shani Oates, current Maid of the Clan of Tubal Cain. Anthologies can often be a less than satisfying reading experience, with the piecemeal nature of the presentation never engendering the focus that a singular work can provide. This is certainly the case here and there was just something a little disappointing about discovering that what I thought was a going to be a focussed book on the mysteries of the Clan of Tubal Cain is, by its very nature, broader and not nearly as specific as its retrospectively applied title promises. In saying that, the essays have been grouped into sections, so there is a semblance of order, with divisions devoted, as the subtitle denotes, to female mysteries, male mysteries, priestly mysteries, and Clan ethos.

Subtitled Mythos, Ethos, Female & Priestly Mysteries of the Clan of Tubal Cain, this is a collection of articles by Shani Oates, current Maid of the Clan of Tubal Cain. Anthologies can often be a less than satisfying reading experience, with the piecemeal nature of the presentation never engendering the focus that a singular work can provide. This is certainly the case here and there was just something a little disappointing about discovering that what I thought was a going to be a focussed book on the mysteries of the Clan of Tubal Cain is, by its very nature, broader and not nearly as specific as its retrospectively applied title promises. In saying that, the essays have been grouped into sections, so there is a semblance of order, with divisions devoted, as the subtitle denotes, to female mysteries, male mysteries, priestly mysteries, and Clan ethos.

The essays that form this collection are taken from various pagan magazines, principally Hedgewytch and Michael Howard’s The Cauldron, but also White Dragon, Pendragon and the New Wiccan. The subject matter falls into the broad remit of the Clan of Tubal Cain, having the same polymathic qualities possessed by Robert Cochrane, drawing on folklore, mythology and general witchlore to create a vision of a coherent and very particular form of witchcraft.

Oates writes in a style not too dissimilar to that of her mentor, Evan John Jones, and fellow travellers Nigel Jackson and Michael Howard, in that it is anthropologically broad and encyclopaedic but not overly critical, casting wide thematic nets that are not always necessarily tethered with specific citations. This net sometimes embraces the works of so-called alternative history, a field that could be said to have something of the magical in itself, since its logical leaps and less than rigorous familiarity with the facts is suggestive of metaphysical paradigm building, where peer-review is less important than an internally consistent worldview. Thus, in Mythopoesis, Laurence Gardner’s Genesis of the Grail Kings is referenced, extensively and uncritically, in a discussion of Mesopotamian cosmology, where perhaps recall to more reliable, or even primary, sources would have been advisable; and would have inspired more confidence.

Mythopoesis introduces the opening section of writings on the mythos of the Clan of Tubal Cain, and, despite my misgivings about Gardner as a source, it is an interesting, well written overview of matters witchcraft and Qayinian, beginning in the broad, speculative world of alternative history before ending with a discussion of ritual tools and praxis. This is followed by a welcome discussion about Goda, the pale goddess of fate in the cosmology of the Clan of Tubal Cain, in which Oates brings together various linguistic traces of the name, as well as summarising Cochrane’s thoughts on the goddess, collected from his various correspondences. The third chapter in this section, is missing, suggesting some great esoteric mystery… or mayhaps just a clerical error.

The book’s abruptly promoted fourth chapter is a dissertation on Hekate and opens the section on female mysteries. Each of these pieces is a broad consideration, and its seems to very much be Oates’ modus operandi to take a core subject as an opportunity to explores related tangents, often bringing them ultimately to bare within a witchcraft frame of reference. Thus the female mysteries are explored from the root themes of courtly love, Salome’s seven veils, the hand of Fatima, Sheela na gigs, and the Day of the Dead (which marks a stylistic diversion from most of the other essays with its more travelogue structure and voice).

Under the rubric of male mysteries Oates is able to consider the Wild Hunt (covered in two essays), the Green Knight (of Sir Gawain fame), and solstice traditions, all presenting a fairly consistent theme of the king of the greenwood. There’s a certain continuity of these themes into the section on priestly mysteries, with arboreal kings figuring in the essay The Divine Duellists, but otherwise the topics at hand are new, with considerations of the Fisher King, the symbolism of cranes, and the mythic analogies of entheogens (which provides summaries of all the usual suspects: Wasson, McKenna, Allegro).

Finally, the section on Clan Ethos could be said to follow the lead of its first essay’s title, Musings on the Sacred, with these contributions being considerably less encyclopaedic than their predecessors, with more of a discursive quality. The most interesting of these are ones that deal more specifically with Robert Cochrane and the Clan of Tubal Cain, fulfilling the original promise of the book’s title. The Mystery Tradition considers the difference between paganism and witchcraft, reflecting on Cochrane’s differentiation betwixt the two, while A Man for all Seasons considers magickal inheritance and Cochrane’s ideas of the witchblood. The remaining essays explore various clan-related ritual procedures, including initiation and the division of ritual forms into three rings of divination, spell-casting and communion.

For a Mandrake publication, Tubelo’s Green Fire doesn’t do too badly in the old formatting stakes, with an overall consistent and perfunctory layout that doesn’t overly interfere with reading. That said, the point size of the body is a smidgen too large, and the margins on all four edges are too tight; as is, naturally, the gutter. This leads to a slightly claustrophobic feeling whilst reading, with even the endnote references rendered in the uniform size of the main body, and the titles in nothing more than a functional larger version of the same typeface. A lack of attention to detail means that each essay retains its original referencing style, and these come in all shapes and sizes, appearing as in-text citations in some cases, and as end notes in others (with even the formatting of these differing between usages). There’s also a few idiosyncratic, but inconsistently applied, punctuation quirks, such as randomly presenting some names, and in some cases, words, within single quote marks; a peculiarity that is then inexplicably compounded still further by occasionally presenting some of these quoted words in italics with no rhyme or reason.

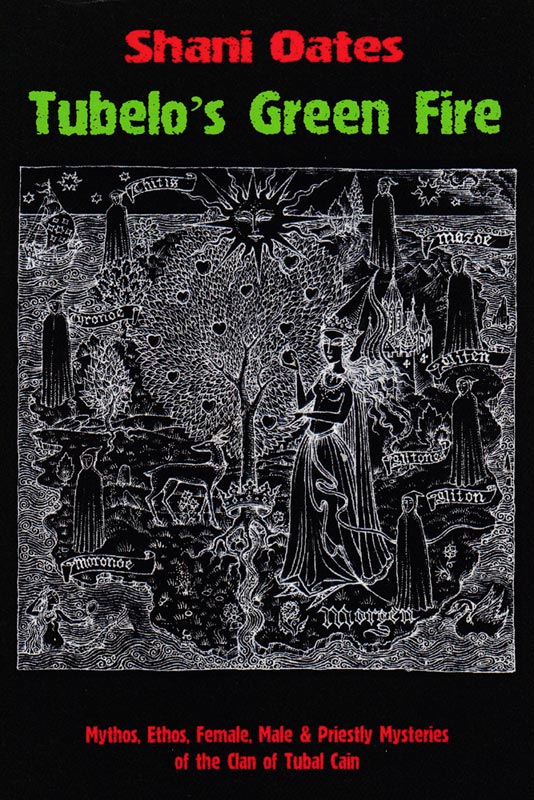

The pages of monolithic typographic colour within the book are occasionally (and I mean very occasionally) interspersed with simply rendered illustrations by Liza Miskievicz. The cover bears an image, The Fortunate Isle, by the always wonderful Nigel A. Jackson, made significantly less interesting by being unimaginatively inverted; and the less said about the accompanying title in an unnecessarily distressed typeface, coloured zombie-movie-green, the better.

Published by Mandrake of Oxford. ISBN 978-1906958077