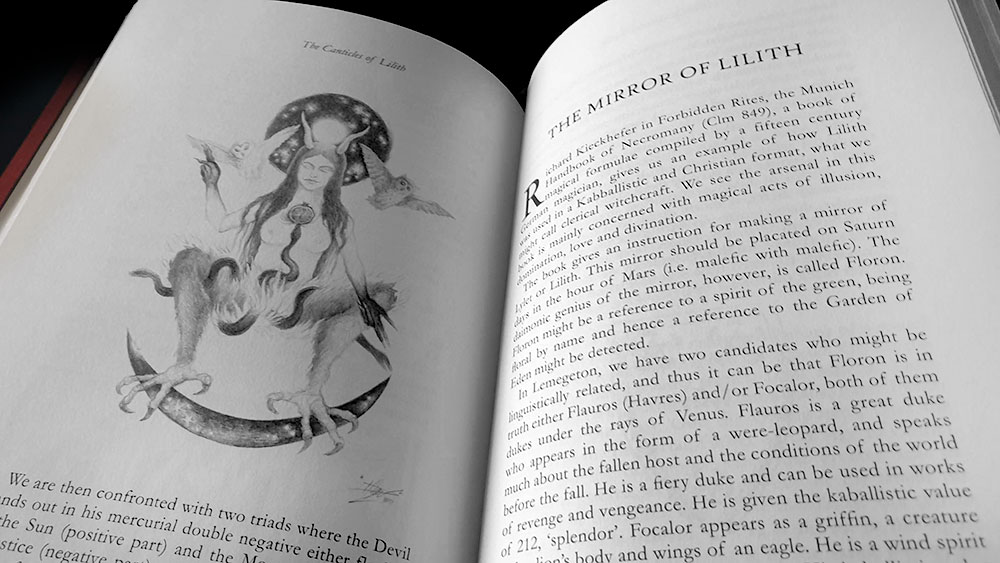

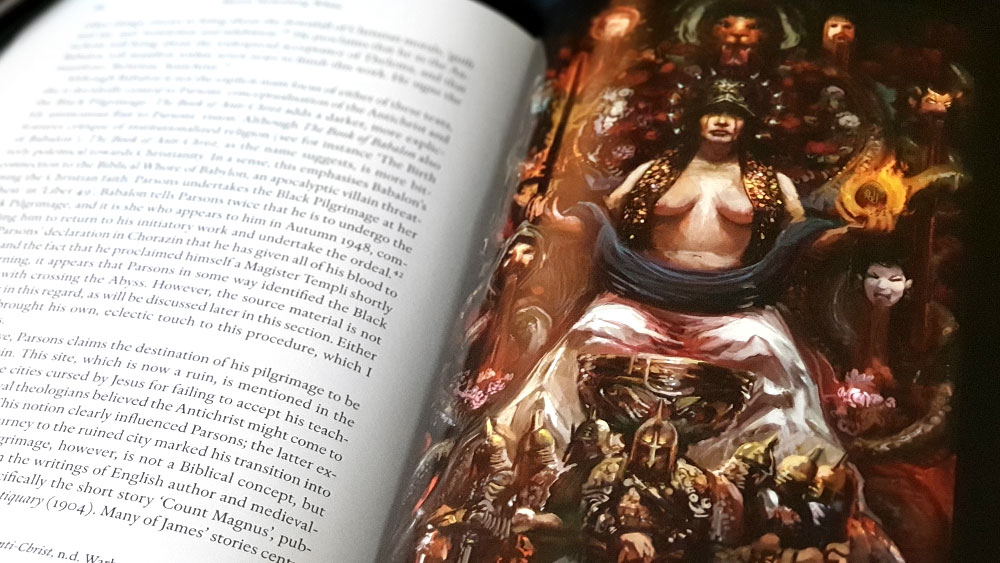

While the output of Troy Books often has a somewhat rustic and grounded feel in their choice of subject matter, reflecting localised folk and witchcraft traditions from different areas of the British Isles, on this, their first release for Troy Books, Nicholaj and Katy de Mattos Frisvold offers something slightly more sinisterly glamorous. As its title makes clear, the focus here is on Lilith, and in particular how she relates to witchcraft, with considerations of her manifestations astrological, Luciferian, Satanic, and erotic, as well as explorations of her multifaceted roles as a vampiric spirit, a Satanic muse, the witch-mother, a spirit of illness, the word of creation, and even the holy spirit herself.

While the output of Troy Books often has a somewhat rustic and grounded feel in their choice of subject matter, reflecting localised folk and witchcraft traditions from different areas of the British Isles, on this, their first release for Troy Books, Nicholaj and Katy de Mattos Frisvold offers something slightly more sinisterly glamorous. As its title makes clear, the focus here is on Lilith, and in particular how she relates to witchcraft, with considerations of her manifestations astrological, Luciferian, Satanic, and erotic, as well as explorations of her multifaceted roles as a vampiric spirit, a Satanic muse, the witch-mother, a spirit of illness, the word of creation, and even the holy spirit herself.

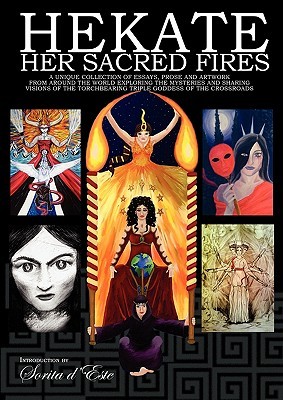

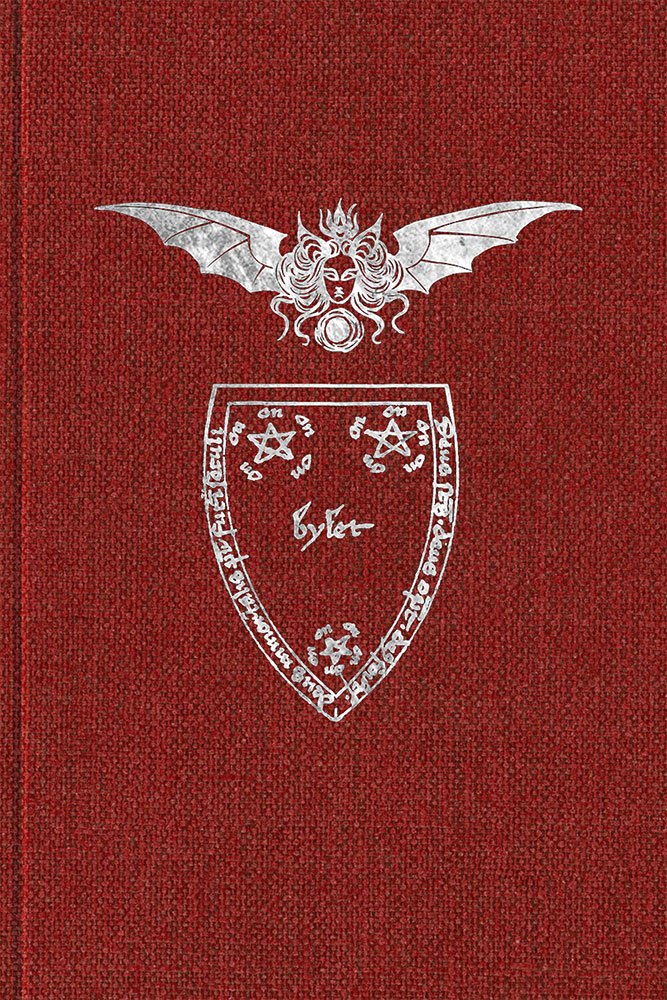

What strikes the reader immediately is the aesthetic quality of the presentation here, with Troy Books replacing their previous, relatively smooth binding with a far more textured one, a gorgeous, thick-thread red cloth that takes the metallic foiling of the cover and spine very well. The interior is equally pleasing with black end papers, a nice weighty paper stock throughout, and formatting that, while functional, is effortlessly professional with it. It is slightly jarring then to be met with the first sentence, suggesting that perhaps the same amount of care should have gone into the editing. This one sentence runs to eight lines of swirling tense, multiple verbs, and minimal punctuation, which we will repeat here in its entirety since nothing else can quite convey all its hallucinatory and exhausting glory. Public health warning: do not attempt to read out loud without a respirator at hand. “Lilith has been tied to the idea of “witchcraft” either as Queen, demoness, vampire, or a spirit of lustful vice and all of these ideas hold a part of her mystery, but for the cunning one she represents the witch-mother herself that with the fallen host and their offspring gave to the fair-daughters of Cain and Seth this special blood that generated the different seed in the world that gave rise to the cunning ones.”

Although thing don’t always approach this befuddling level of complexity, it is indicative of the type of language and structure used throughout this book. Sentences frequently feel as if they are verging on chaos, be it through a breathless running-on, a concatenation of verbs that disorientates with a surfeit of opposing actions, or in the repetition of particular words in a single sentence when a synonym would suffice. There’s also an inconsistent approach to punctuation, where sometimes it is critically absent, while in other instances, its presence is superfluous. What makes this particularly confusing is that the style of writing, and the coherence thereof, seems to shift, possibly due to the double author credit, or due to parts having been written at different times. This is furthered by the way in which there has been no attempt to align the styles, either during the base writing, or at the editing stage. Indeed, one imagines that the degree of editing needed here would have amounted to a complete rewrite of the manuscript, almost negating any author’s credit. However, even a cursory proof-read seems to have been skipped, as things like errant or entirely missing words, not to mention a general vibe of unreadability, have been left intact.

In all, it is very distracting and it is impossible to escape, especially when some sentences have to be read several times to get the intent, or when the reader has to pause to get over unintended comedic moments engendered by the poor structure. Our favourite is the mental image of a caudal humanity when a discussion of huldre makes the statement: “These forest people were said to be creatures created before mankind with a tail.” Hang on, when was mankind created with a tail?

It really is a shame, particularly because Nicholaj and Katy de Mattos Frisvold clearly have an enthusiasm and passion for their subject, with their devotional fervour being quite palpable. There’s a feeling that this should be a poetic book, with florid turns of phrase adorning the language, like Peter Grey’s giddy Apocalyptic Witchcraft or his paean to Babalon in The Red Goddess, but yes, they’re not Grey, with none of his deft command of prose or his attention to detail when proofing and refining. Ultimately, a disservice is done to the book and to its very subject, especially since an unwillingness to write and edit in a credible manner makes one immediately mistrust the credibility of the very words themselves.

The Canticles of Lilith is divided into three parts, with the first two dealing with the theoretical and historical, and the third providing some practical elements. The first of these, The Lilithian Constellation, casts its net pretty wide, largely dealing not with Lilith herself, but with similar themes in adjacent cultures. By its very nature, in which Lilith is effectively treated as a vibe, this is a broad and uncritical survey in which anything slightly resembling Lilithian traits can be picked out, using confirmation bias to build a comprehensive, albeit circumstantial, picture of her as persistent and universal. As we are talking metaphysics here, there’s no need to track, or even claim, some historical path of thematic or cultural diffusion, but even with that allowance made, it can sometimes feel a bit tenuous. This is particularly noticeable when several pages are devoted to discussing Stregoneria with nary a mention of Lilith, save towards the end when there are attempts to fold her back into the discussion. It feels almost as if this was dropped in from somewhere else, which is exactly what happened, as this is Nicholaj de Mattos Frisvold’s article Stregoneria: A Roman Furnace, which appeared in Scarlet Imprint’s 2013 anthology Serpent Songs. Amusingly, the 2013 version reads a lot better, as Scarlet Imprint’s copy editor Troy Chambers mush have done a fair bit of work on it, and as a result, that incarnation is deceptively readable; whereas the version copied into this new book is presumably closer to the unpolished original.

The book’s focus makes a welcomed shift to Lilith specifically in the second section, The Atmosphere of Lilith, though once again there is a feeling of things being all over the place, both in the general narrative and in sentence construction, with the tortuous writing and awkward phrasing making it a chore to get through. A favourite line, giving some much needed comic relief, comes early on in an attempt to paint Lilith’s grand history, using a strange and clumsy Mesozoic simile: “She rose from being a spirit fated to die, like a dinosaur – but still her legacy and prominence spread across the worlds as history advanced.”

The difficulty of following this addlepated text is aided and abetted by underused and inconsistent formatting, such as when references to sources texts blend into the body because they aren’t italicised, except when they suddenly are, with things getting to a ridiculous level in one reference to The Alphabet of Ben Sira in which only the second half of the title is in italics. Indeed, this whole section is rough, with sources texts from all over the place being introduced, often with zero context, giving the impression that they represent a cohesive body of lore, but with no regard to gulfs either cultural or temporal. There is the statement that Lilith is mentioned several times in “the Nag Hammadi or Dead Sea Scrolls” as if the two collections of texts are the same thing, but no actual examples are given. Instead, the paragraph refers, by comparison, to the strange woman ambiguously mentioned as a personification of temptation in Proverbs 2:16-19, with Friswold adding the bold claim that the biblical text describes her as having horns and wings (it doesn’t). One assumes that Friswold is referring to the Wicked Woman who appears in a short sapiential poem from the Dead Sea Scrolls, catalogued as 4Q184. She is an ambiguous figure who is frequently compared to the Strange Woman of Proverbs, but none of that is explored in any detail here, as if a secondary reference has been poorly transcribed, with no real investigation of the source texts. This also speaks to a flaw in the overall approach, in which a lack of rigour is combined with unwarranted certainty. There is much that could be made in investigating the Wicked Woman of 4Q184 as well as other unnamed scriptural figures as analogues of Lilith, getting into the weeds and assessing strengths and weaknesses to such arguments. But none of that occurs here, and the opportunity is wasted, replaced with categorical claims that these constitute specific references to Lilith, almost as if she is named as such within them.

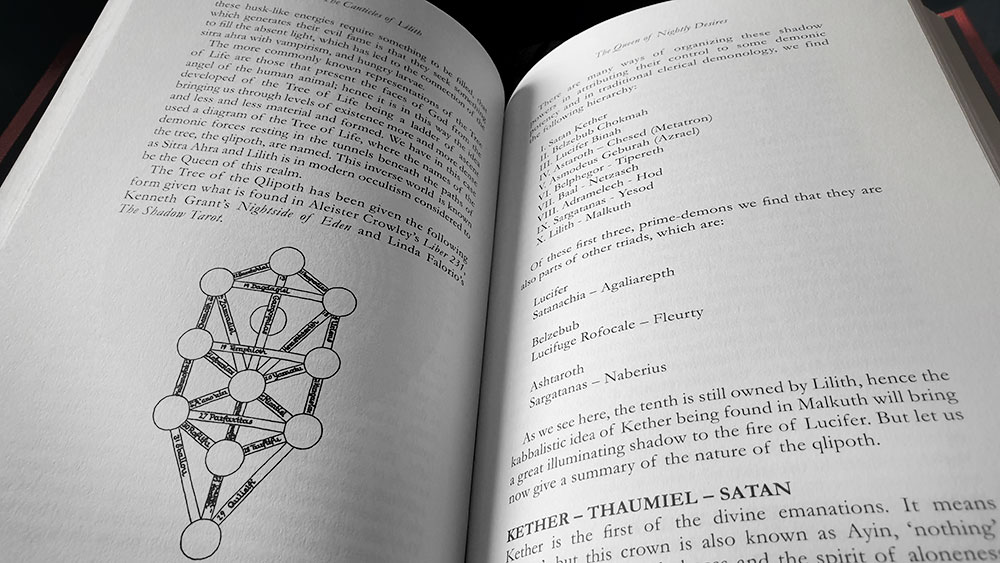

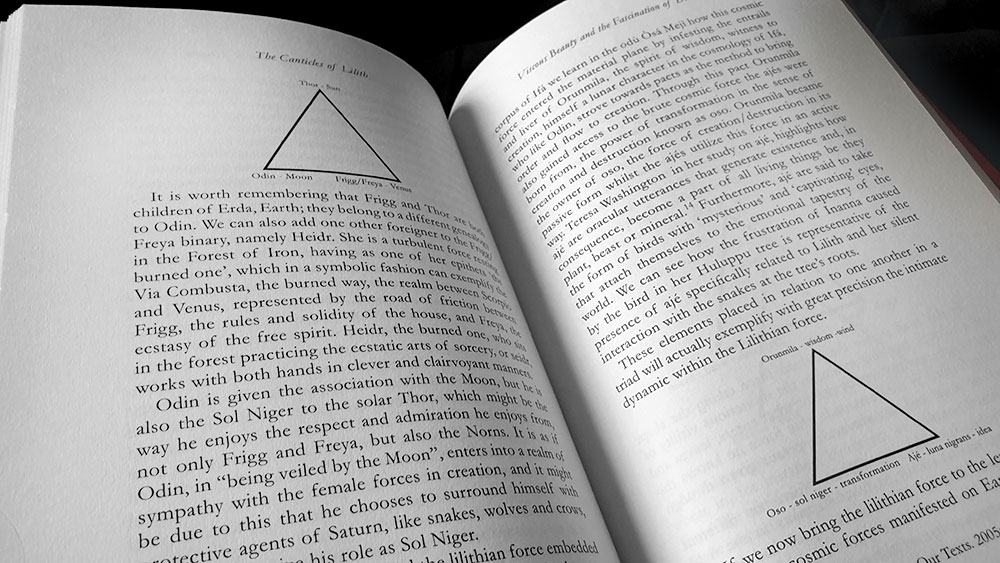

The historically amorphous overviews of this section eventually lead to a consideration of the sephira and corresponding qlipha of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, culminating with Lilith’s association with Malkuth. This is a thorough consideration though, and not limited to just Malkuth, with on average a full page of information about each of the other sephiroth/qliphoth being given. Matters then turn back to non-Mesopotamian folklore, with more exploration of figures that can be compared to Lilith, with a particular focus on her association with disease, pulling variously from Greek mythology, Romani folklore and even Norse mythology. One of the key approaches here is to take three figures from a mythos and draw a triangle between them as if the space within connotes some great importance in embodying a ‘lilithian force.’ It’s all a bit arbitrary, putting, for example, Óðinn, Þórr and Frigga/Freyja (because, sure, why not treat them like they’re the same goddess) at each point, as well as bizarrely associating Þórr with the sun, Óðinn with the moon and Frigga/Freyja with Venus. There are also some weird little moments in this barrage of frequently context-lacking folklore, such as the head-scratching claim that in some unspecified legends, Tubal-Cain is the son of Cain and Eve. And then there’s this section’s opening sentence, stating that in his Ars Poetica, Horace “translates Lilith to Lamia,” a claim which appears to have been cut and pasted from a long-since-revised version of the Lilith page on Wikipedia. There’s no explanation as to how the Roman poet was supposedly translating Lilith to Lamia, and no context for the reference to Lamia within his guide to poetics, not even a mention of who Horace was. This abrupt statement thus comes across as something glommed but unexplored from an old Wikipedia page, employed as a pointless opening to the discussion that follows concerning Lilith’s similarities with Lamia.

The excessive excoriation that has typified this review comes from a place of disappointment rather than malice, because The Canticles of Lilith is a book that promises much and could have been so much more if attention had be paid to the quality of writing, in both a mechanical sense, and in the very presentation of the information. There is much that is included here in a raw manner, but it is treated so clumsily and awkwardly, that it is just sad. Such is the degree of disappointment that it is difficult not to list every error that irritates as one progresses through the book, so, for our sanity, we shall draw a line in the sand and move on to the final section, The Rites of Lilith’s Basilica, where things take a more practical turn. These entries are largely invocatory in nature, with a liturgy of a noticeably purple persuasion, with rituals for Hekate and Ishara thrown in too because why not? Running to 55 pages, this is a decent collection of workings, and there’s enough variety in approaches and formulae that for those inclined, there’s much here that can be put to use.

The excessive excoriation that has typified this review comes from a place of disappointment rather than malice, because The Canticles of Lilith is a book that promises much and could have been so much more if attention had be paid to the quality of writing, in both a mechanical sense, and in the very presentation of the information. There is much that is included here in a raw manner, but it is treated so clumsily and awkwardly, that it is just sad. Such is the degree of disappointment that it is difficult not to list every error that irritates as one progresses through the book, so, for our sanity, we shall draw a line in the sand and move on to the final section, The Rites of Lilith’s Basilica, where things take a more practical turn. These entries are largely invocatory in nature, with a liturgy of a noticeably purple persuasion, with rituals for Hekate and Ishara thrown in too because why not? Running to 55 pages, this is a decent collection of workings, and there’s enough variety in approaches and formulae that for those inclined, there’s much here that can be put to use.

The Canticles of Lilith has been released in the traditional Troy Books range of editions: paper, standard hardback, and already sold-out special and fine editions. All have a page count of 264 on 90gsm cream paper stock, with the paper edition featuring a gloss laminate cover showcasing a painting by Katy de Mattos Frisvold. The standard hardback edition is bound in a dark red cloth with a spine title and a crest-like device on the cover blocked in silver foil, finished off with black end papers, and black head and tail bands. The 125 copy special edition replaces the cloth binding with a black faux leather, and silver foil blocking on the cover and spine, with red end papers, red head and tail bands. Finally, the fine edition was hand bound in a red leather with blocking in black foil to the spine and cover (with a different sigil design than the other editions), all housed in a fully-lined black library buckram blind embossed slip case.

Published by Troy Books