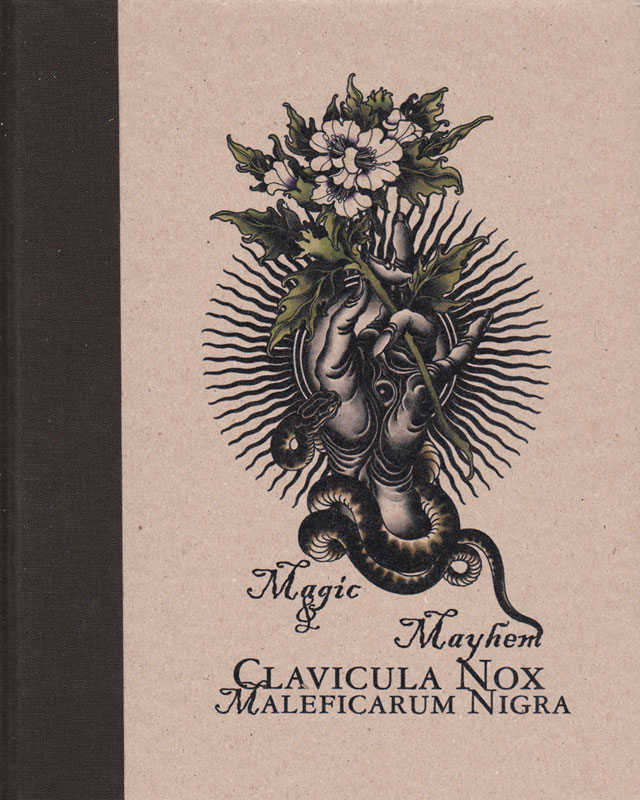

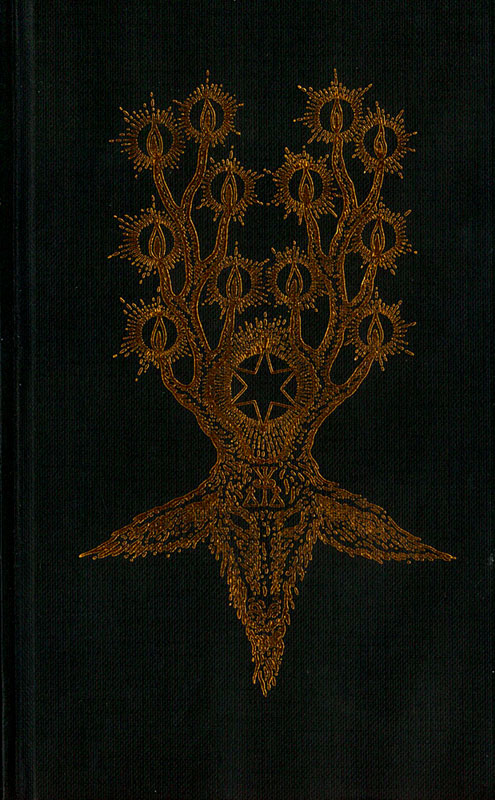

This beautifully presented and compact little book brings together, as the title suggests, thirteen rites for the Old One. And, as also indicated by this title, the cover image and the abundance of horns throughout the book, this Old One is most unashamedly the Devil of folklore, viewed through the lens of Traditional Witchcraft. Distinct from the church’s concept of Satan, this Devil still presides over evil, but these are the perceived evils of personal freedom, indulgence and ecstasy. He is, as Gemma Gary explains in her introduction, the bearer of forbidden gifts, the opener of the Way Betwixt, and the old spirit of the land.

This beautifully presented and compact little book brings together, as the title suggests, thirteen rites for the Old One. And, as also indicated by this title, the cover image and the abundance of horns throughout the book, this Old One is most unashamedly the Devil of folklore, viewed through the lens of Traditional Witchcraft. Distinct from the church’s concept of Satan, this Devil still presides over evil, but these are the perceived evils of personal freedom, indulgence and ecstasy. He is, as Gemma Gary explains in her introduction, the bearer of forbidden gifts, the opener of the Way Betwixt, and the old spirit of the land.

Gary is at pains to point out that these rituals make no claim to any great antiquity or hereditary descent, but rather draw on extant themes that are well documented in the folk record. There is, naturally, a focus on matters Cornish, with several dealing with the Bucca, and these rites act as a concise adjunct to much of the material found in Gary’s more explicative Traditional Witchcraft: A Cornish Book of Ways. This book is not without its own explications, though, and each ritual is preceded by a brief explanation providing its context and attendant folklore. Gary defines these thirteen as rites of vision, dedication, initiation, consecration, empowerment, protection, illumination, union, transformation, devotion and sacred compact.

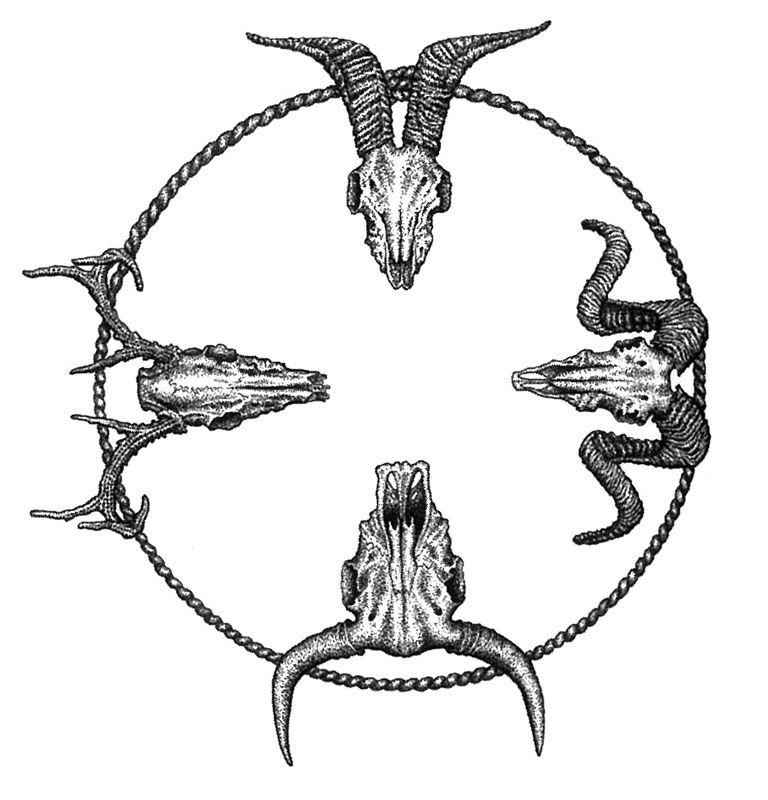

It is a sacred compact to the Devil as the Man in Black or Dark Man that acts as the first rite in this collection, establishing a relationship and setting the scene for that which is to come later. This is a simple procedure, effectively an elaborated statement of intent that is preceded by a little ritual structure (thrice utterance of the Lord’s Prayer backwards in a remote location), and followed by a period of reflection during which the Man in Black may manifest in some manner. This compact is indicative of Gary’s ritual style: fairly succinct with some nicely written liturgy. There’s not much in the way of obscure ingredients, elaborate correspondences, complicated formula or extended periods of time, with the rites having more of a feel of hedgewitch pragmatism. The only temporal imperatives are fairly standard things like midnight and during a full moon, while the ingredients and tools list tends to speak to things that anyone embracing the aesthetics of Traditional Witchcraft will end up acquiring (if only too look cool in their altar photos on Facebook): iron nails, an iron knife, a scourge, horned skulls, dragon’s blood incense and a stang. Circles abound in these rituals, as does the use of mill treading as a way to generate power and there is a general feeling of getting out amongst it, with hands dirty from soil and the soot of flaming torches.

It is the written word in which Gary excels, with her incantations having an archaic quality that doesn’t wrap itself up in arcane complexity (or misapplication), and instead flows with a degree of authenticity. This is aided by the occasional use of rhymed couplets and alternate rhymes, which gives some of the words a folky familiarity, as if they’ve been overheard in playgrounds for centuries; obviously those would be rather spooky playgrounds.

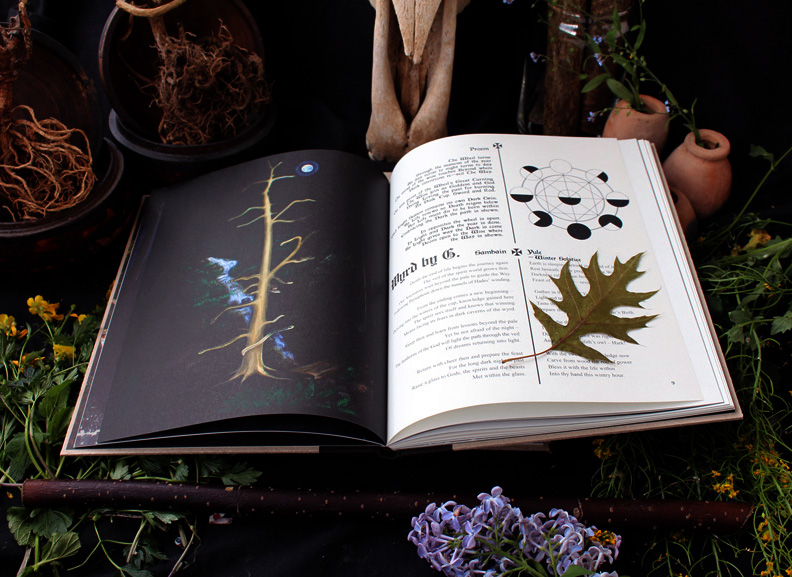

At 187 x 114mm, The Devil’s Dozen is a small volume that has a diary-like quality to it, fitting comfortably in a single hand or handbag for easy transportation to ritual locales. Its slight width does lead to rather snug gutters that do require the book to be splayed wide in order to catch everything and having the, one supposes unintentional, side effect of a sense of bibliographic intimacy as one spreads and peers in.

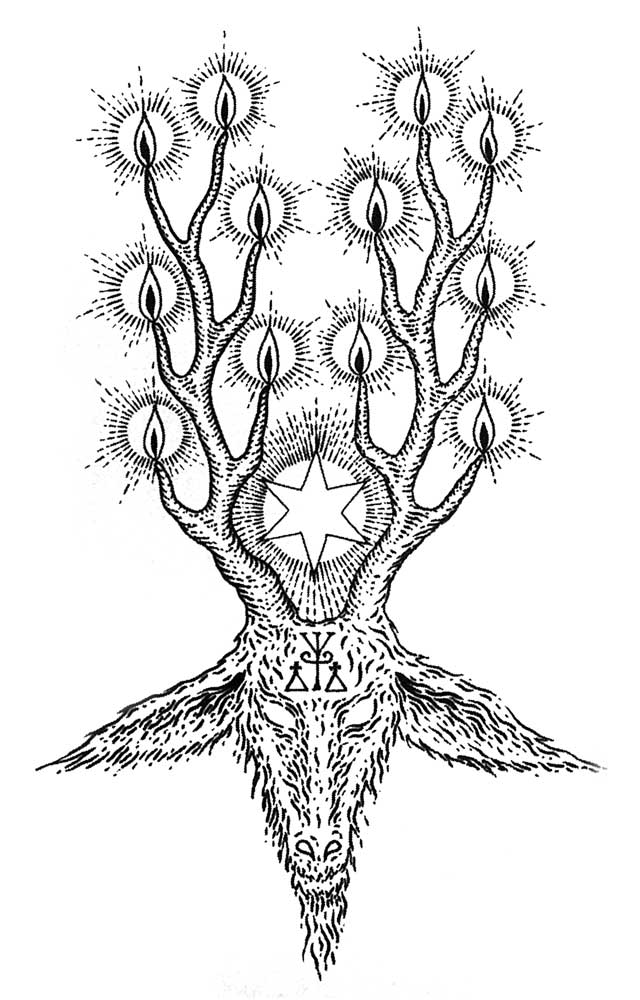

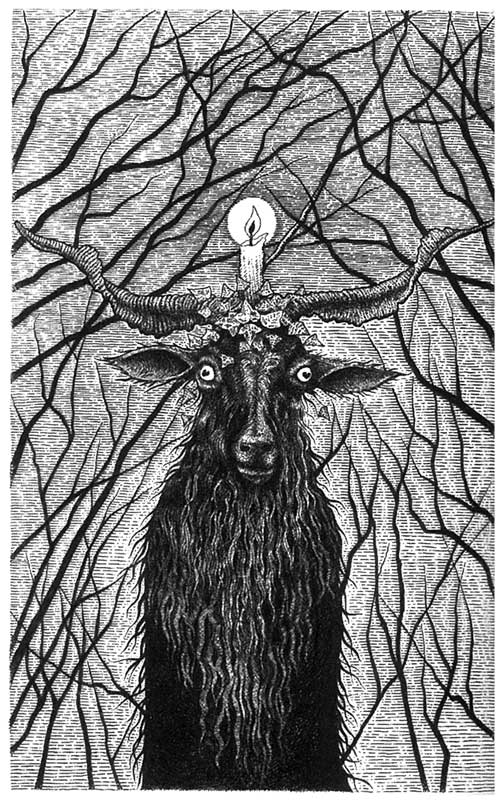

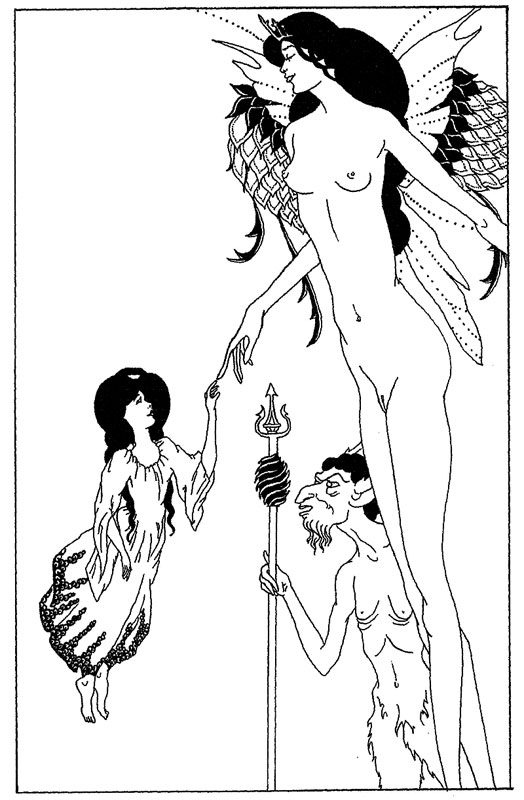

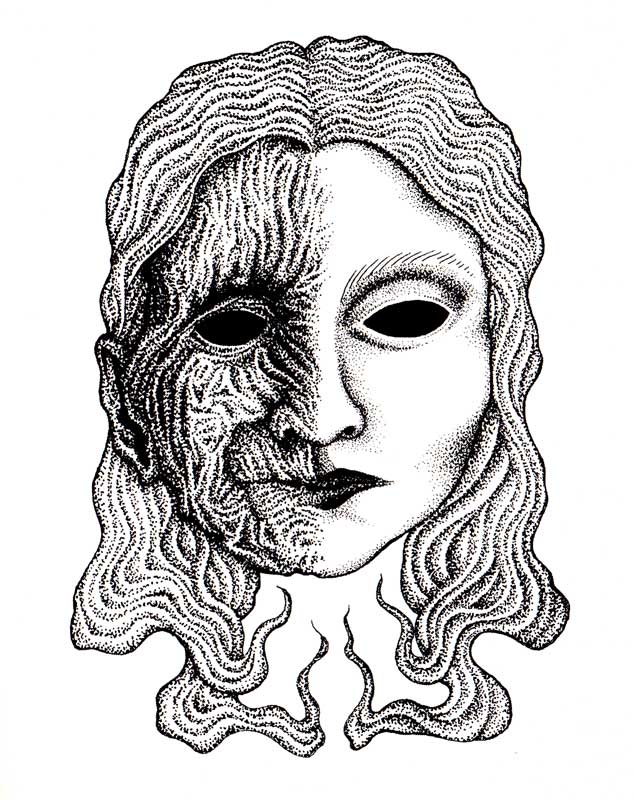

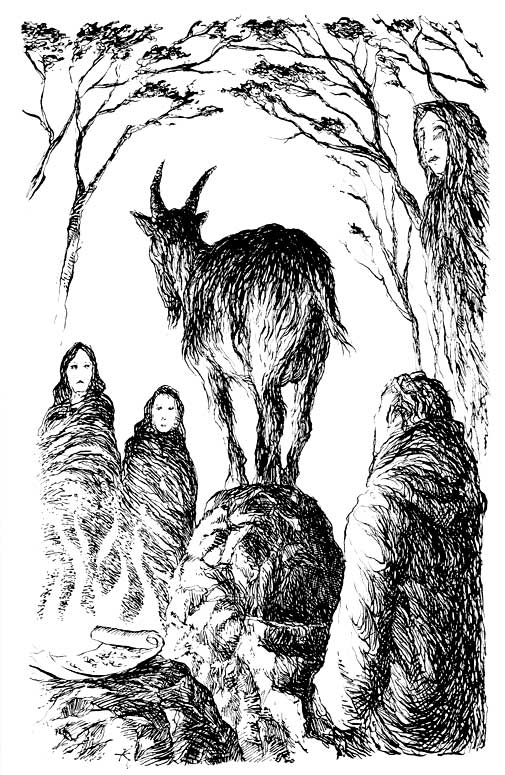

As with most if not all of Gary’s books, The Devil’s Dozen is illustrated by the author herself in her trademark stippled style of pen and ink. These are usually found as full-page preludes to the various rites, while a veritable study of horned skulls is dotted throughout the work as fillers. In addition to these in-body illustrations, there is a selection of black and white plates by Jane Cox, providing a photographic record of some of the procedures contained herein, along with various apposite images of witchcraft-related accoutrements.

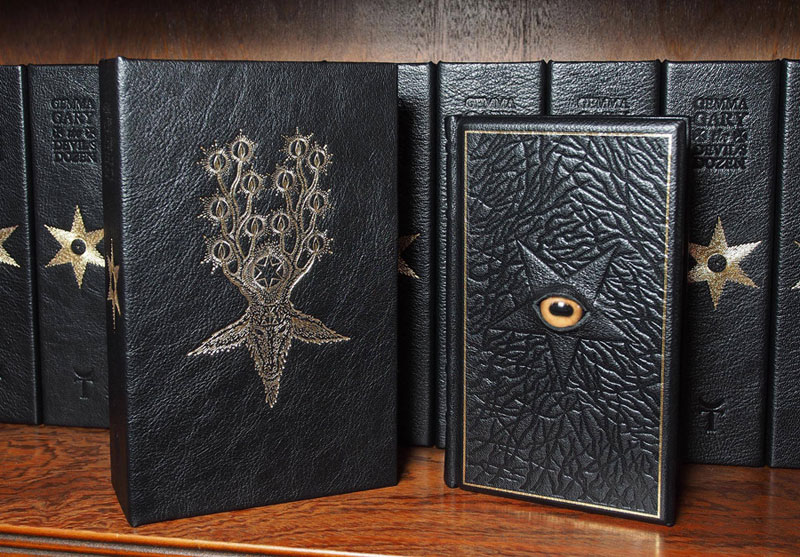

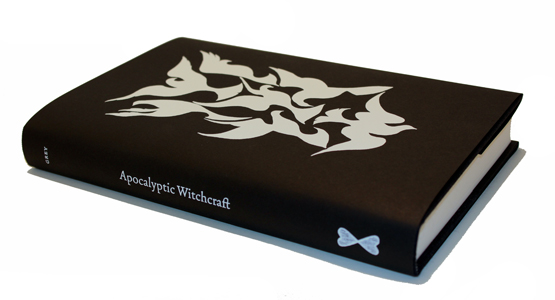

The Devil’s Dozen is published in four editions, each consisting of 160 pages, along with eight black and white photo plates. In addition to a regular paperback version, there is a hardback incarnation which attains a pretty nice level of quality for what is the affordable standard edition with its 80gsm cream paper stock, black case binding, copper foil blocking on the front image and the spine, hunter green endpapers, and green and black head and tail bands. There are two special editions, the 300 hand-numbered Special Edition bound in dark, grained green recycled leather fibres, with the cover and spine elements in blocked in gold foil, green end papers and green and black head and tail bands. The even more luxurious Special Fine Edition is suitably limited to 13 sold out hand-numbered copies in full black goat leather binding with a gold border and a blind embossed thicket of branches on the bevelled front board, inset with a high quality glass goat’s eye cabochon. This is further housed in a full goat leather solander box, blocked in gold and lined.

Published by Troy Books.