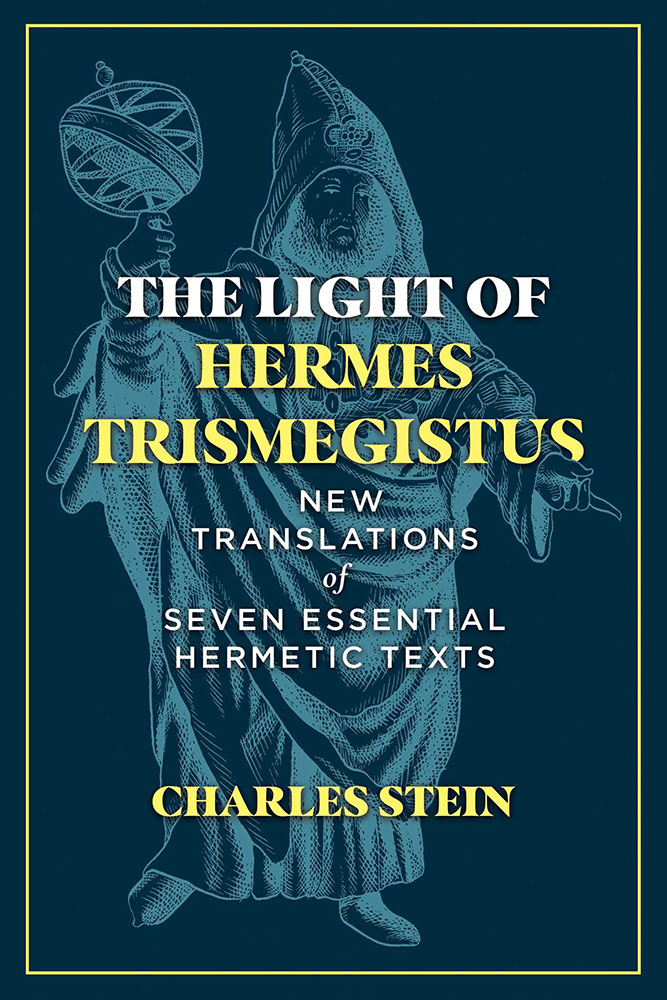

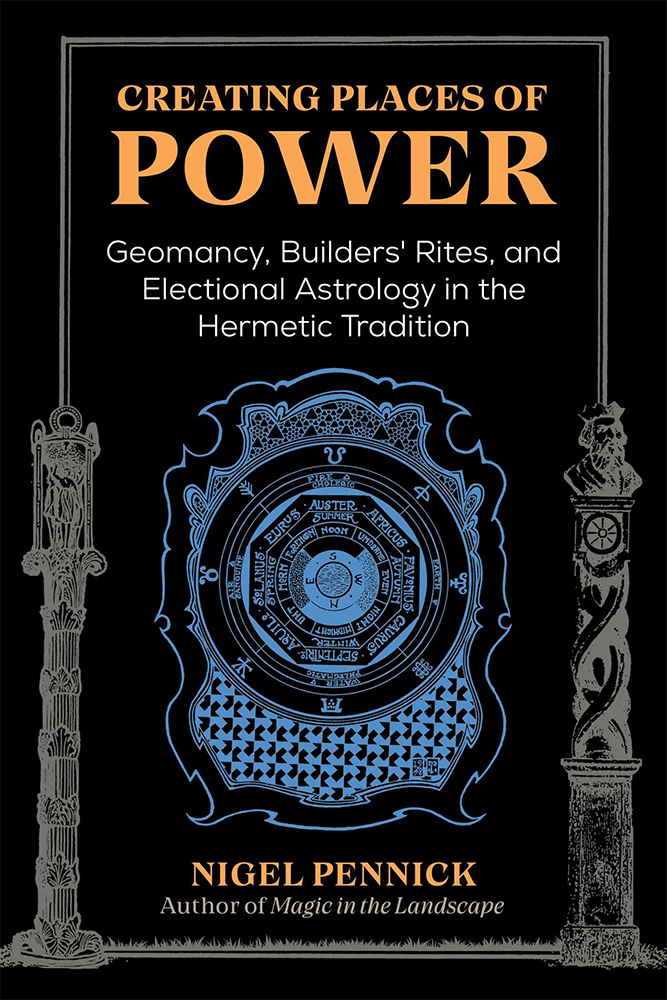

Subtitled Geomancy, Builders’ Rites, and Electional Astrology in the Hermetic Tradition, Nigel Pennick’s Creating Places of Power was originally published in 1999 by the now defunct Capall Bann press. That edition had the ambiguous and open-ended title of Beginnings, and was accompanied by a subtitle that referred to the European tradition instead of the Hermetic one. As it turns out, that earlier subtitle is more accurate, because the brief here is one that embraces folklore and traditions from across Europe, rather than anything that could be specifically categorised as Hermeticism per se. For what it’s worth, Hermeticism does seem to be quite the thing as the moment for Inner Traditions, with this being one of several recent books up for review that mention it in their title.

Subtitled Geomancy, Builders’ Rites, and Electional Astrology in the Hermetic Tradition, Nigel Pennick’s Creating Places of Power was originally published in 1999 by the now defunct Capall Bann press. That edition had the ambiguous and open-ended title of Beginnings, and was accompanied by a subtitle that referred to the European tradition instead of the Hermetic one. As it turns out, that earlier subtitle is more accurate, because the brief here is one that embraces folklore and traditions from across Europe, rather than anything that could be specifically categorised as Hermeticism per se. For what it’s worth, Hermeticism does seem to be quite the thing as the moment for Inner Traditions, with this being one of several recent books up for review that mention it in their title.

This is not the only geomancy-themed work that Pennick has published in recent years, with his Magic in the Landscape, another reissue of an older title, being released in 2020 by the Inner Traditions imprint Destiny Books. Perhaps expectedly, there is some thematic overlap here, with Pennick having the same concerns across both titles, though his tone is remarkably different. As is his style, Pennick begins in opposition, positioning the themes of his book against the modern world. This is a typical and de rigueur screed against modernity, though it contrasts with Magic in the Landscape by virtue of its vituperative tone. While, as our review documents, Pennick has an almost resigned and philosophical manner when discussing the desacralisation of the landscape in Magic in the Landscape, here he lets fly with a condemnation of modernity, aiming his fulmination quite far back with a particularly impassioned and scathing attack on the Italian Futurists, and their love of speed and the machine. Such is the disproportionate level of excoriation that it almost seems personal, as if Pennick’s childhood puppy had been run over by an automobile recklessly driven by Filippo Marinetti doing his best Toad of Toad Hall impression, or something.

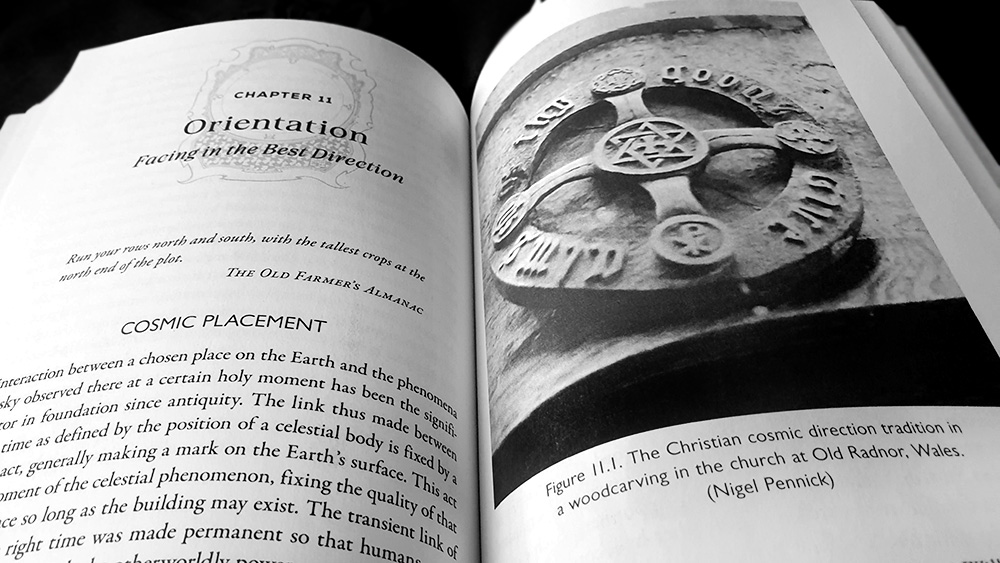

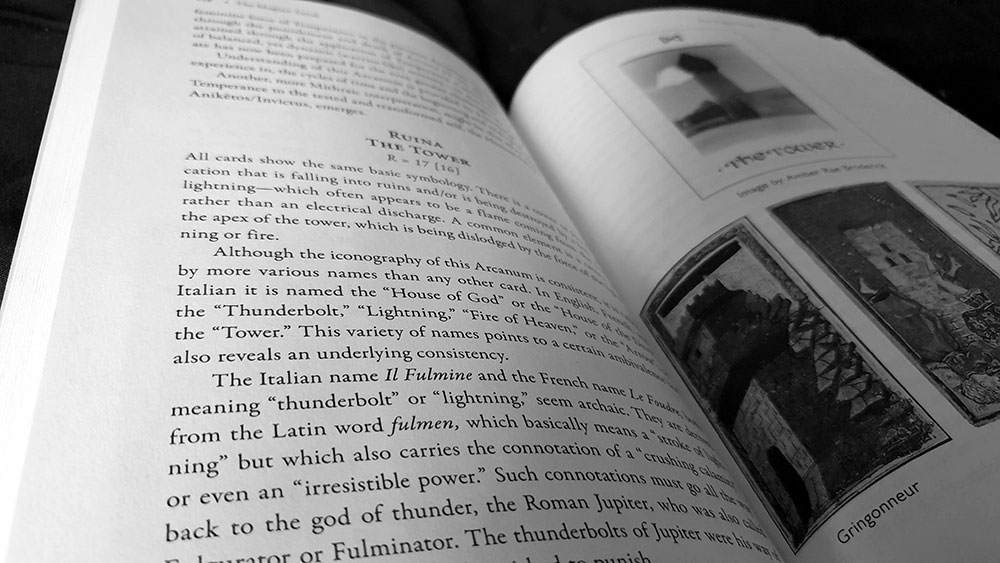

Speaking of speed, Pennick proceeds at a fair click, dividing his book into fourteen chapters, each formatted with a large point size, lots of space, and plenty of images; with at least one across almost every spread. He opens with Patterns of Existence: Consciousness, the Gods, and the Stars, a chapter principally of theory, considering ideas about place within the cosmos, including the aforementioned condemnation of modernity and Marinetti.

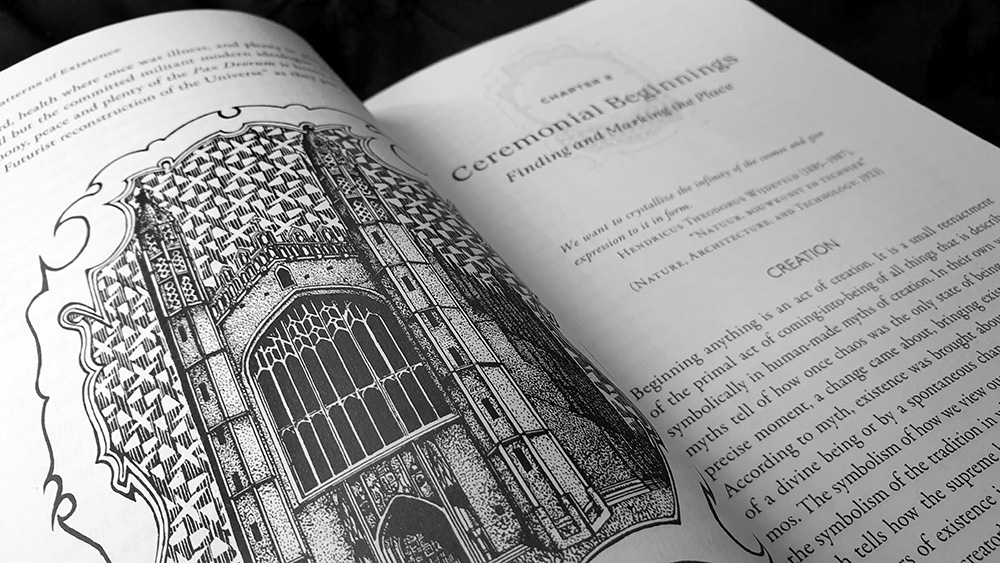

The following second, third, fourth and fifth chapters feel very much like pieces cut from the same cloth, quite literally creating the book’s foundations with a consideration of how special locations might be found, prepared and built upon. In Ceremonial Beginnings, Pennick briefly presents the ways in which a potential place of power could be found and marked, while Foundation discusses the use of offerings and sacrifices to imbue a site with a spirit of place. Whilst Consecration, Evocatio, and Blessings addresses the sacred and the profane in terms of consecrating such locations, while Symbolic Foundation deals with traditions surrounding the laying of the First Stone within structures.

Due to its surfeit of images, this section flies by, with the chapter divisions barely noticeable. Indeed, such is the wealth of pictures that it can be hard to follow the main body text in places, broken up as it by the many large and full page illustrations and photographs that are sometimes followed by still more similarly sized pictures, each annotated with their captions. The end result is a literal, if not literary, page turner, in which handfuls of pages can be knocked out in seconds. Pennick does also keep the written pace coming though, pulling temporally diverse examples from across Europe, with barely a moment to breath. This does, inevitably, create a sensation much discussed in previous reviews of Pennick’s work, where it seems like information is being dumped ungracefully onto the pages, instance after instance, with little exegetical cartilage to tie it all together or slow the pace for a breather. This is compounded by a lack of consistent citing, with a few works being sourced within the body with author and title, whilst the less worthy (accounting for the majority of the information here) remains citation free. There is a bibliography and list of sources at the end of the book, but without any connection between that and the main text it’s largely useless.

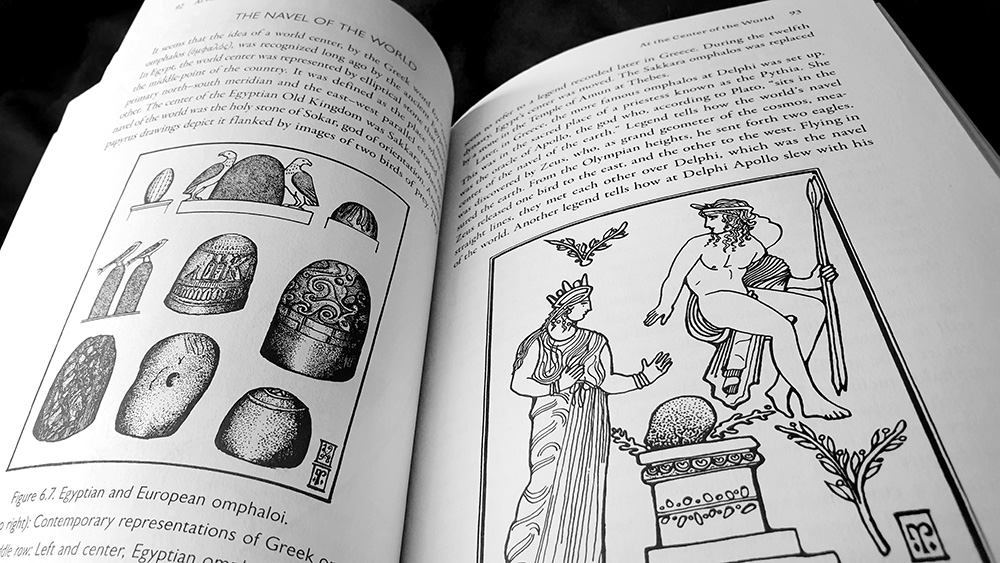

The structure of Creating Places of Power is logical and considered, meaning that, having now established the foundation in the preceding chapters, Pennick turns his focus towards the centre, looking at centriole cosmic symbols like the omphalos, as well as axial devices such as the World Column and the World Tree. Then, in the following two chapters, the journey continues out from the centre, with considerations of the eightfold division of the world, and the symbolism of the eight wind as embodiments of these directions.

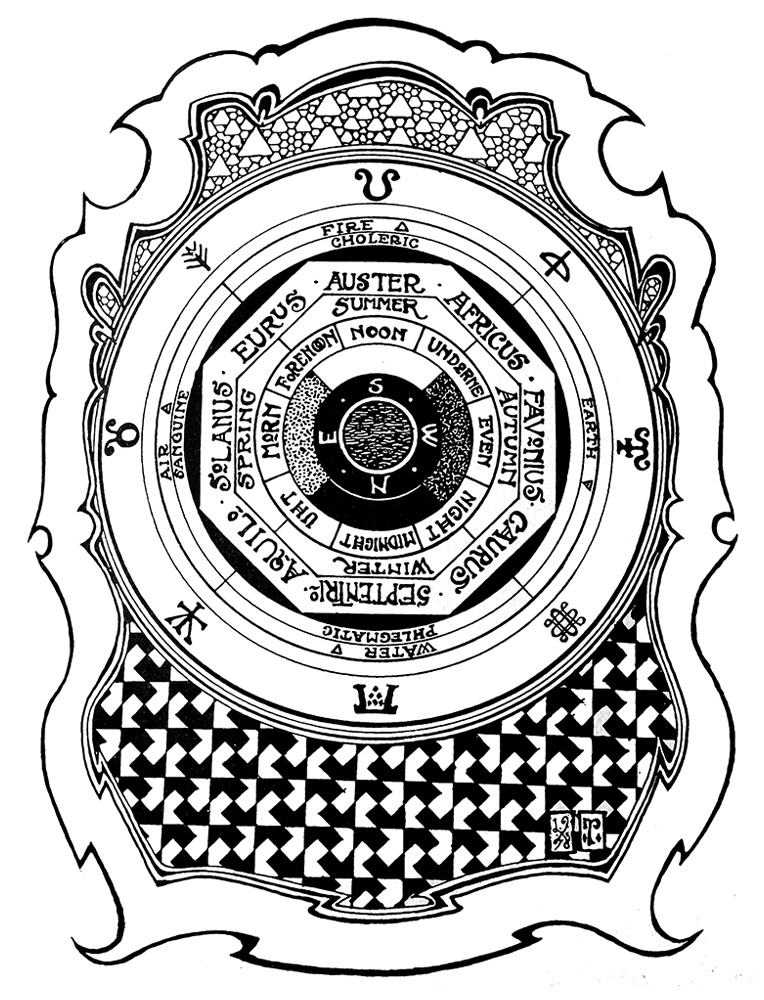

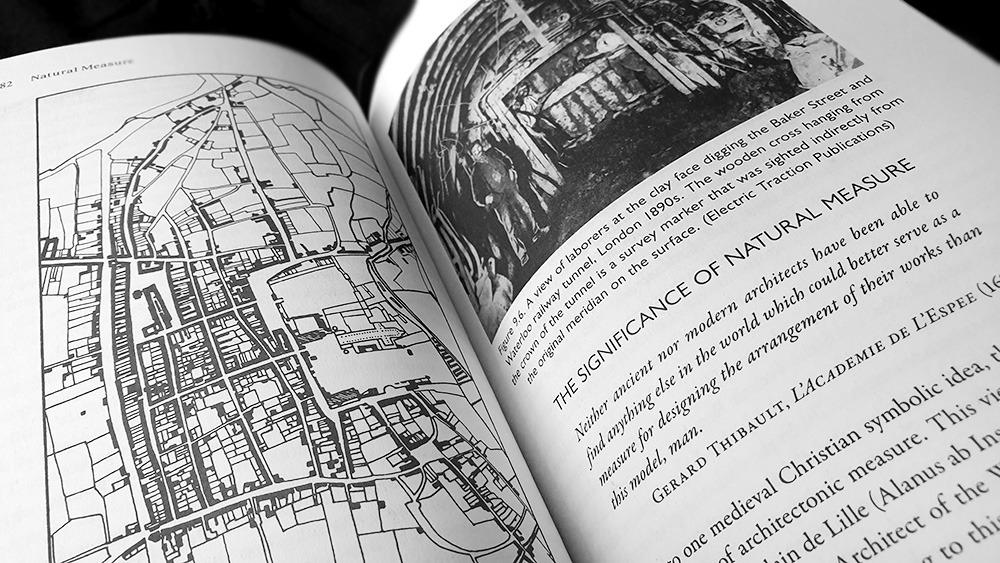

This focus on the centre and its emanations continues into the two subsequent chapters and their documentation of two methods of understanding the world: physical measuring (in particular the use of units of measurement derived from nature), and the telling of time (primarily from the shadowy interaction betwixt gnomon and sun). It is here that Pennick kicks it into curmudgeon mode, having otherwise kept it largely in check after the opening invective against the Futurists. Pennick really seems to have it in for the metric system, which he emotively describes as having being imposed upon people as part of a program of rationalisation, with the “decimalization of the world” having grown apace since the French revolution whose revolutionaries believed it was the only way to live. Rather than these new-fangled ‘globalist’ methods of measuring, Pennick prefers it old school and natural, where things were measured by the other things around it, rather than in abstract units. The most obvious being the original and rather literal unit of a foot, which rather than being the standardised 12 inches (boo, hiss, begone Satan) was whatever the length of the measurer’s foot. Given the innate variance associated with that appendage, I think I’ll stick with standardisation if it’s all the same. Understandably, Pennick is also rather unimpressed with modern time keeping, and predicates olden days local solar-derived time over the modern world’s standardised time zones. The most vociferous ire is saved for daylight saving time, described as a ‘confidence trick’ ‘devised by propagandists’ that “still works today, unquestioned by the vast majority of people” – wake up, sheeple, do your own research!

Pennick concludes with a handful of other chapters circling similar ideas to that which has preceded them, discussing the use of centriole symbolism in street designs, favourable days in the calendar, and the principles of electional astrology and their use in determining the correct time for rites and ceremonies. At 328 pages including appendices, index, glossary and bibliography, Creating Places of Power looks like it should be a weighty read, but due to the aforementioned wealth of images, and generously proportioned text formatting, it’s a deceptively brisk undertaking. In some ways, it is a very specialised book whose thematic appeal may be limited but Pennick approaches his subject matter with the vigour and detail of someone for whom it most certainly does appeal; which may account for those moments when the passionate invective feels, to this layperson, just a tad disproportionate.

Text design and layout come at the hand of Debbie Glogover, who sets the body type in Garamond, with Grand Cru as the title face, and Gill Sans, Kapra Neu and Nexa as the other display faces. The illustrations are a combination of photographs and archival graphics, with a large proportion of works contributed by Pennick himself, notably a series of well-executed escutcheon-based diagrams mapping out concepts like the wheel of the year or the eight winds.

Published by Inner Traditions