At Scriptus Recensera we are avid fans of Andrei A. Orlov and his rather singular focuses on Jewish Pseudigraphia; and in particular the apocalyptic literature of the Second Temple period. Whereas the previously-reviewed Demons of Change, like many of his other books, drew significantly on the second century Apocalypse of Abraham, here the texts of choice, whilst still being associated with or indebted to Second Temple Apocalyptic literature, are from, quelle surprise, the Enochic tradition. Four of these Enochic works provide the book’s triadic structure of three long chapters, though these act more like sections, considering that the total page count for this book’s copy is 223 pages. Chapter one largely addresses the Book of the Watchers from 1 Enoch, whilst 1 Enoch also provides the focus for chapter two, and then 2 and 3 Enoch are the source for chapter three.

At Scriptus Recensera we are avid fans of Andrei A. Orlov and his rather singular focuses on Jewish Pseudigraphia; and in particular the apocalyptic literature of the Second Temple period. Whereas the previously-reviewed Demons of Change, like many of his other books, drew significantly on the second century Apocalypse of Abraham, here the texts of choice, whilst still being associated with or indebted to Second Temple Apocalyptic literature, are from, quelle surprise, the Enochic tradition. Four of these Enochic works provide the book’s triadic structure of three long chapters, though these act more like sections, considering that the total page count for this book’s copy is 223 pages. Chapter one largely addresses the Book of the Watchers from 1 Enoch, whilst 1 Enoch also provides the focus for chapter two, and then 2 and 3 Enoch are the source for chapter three.

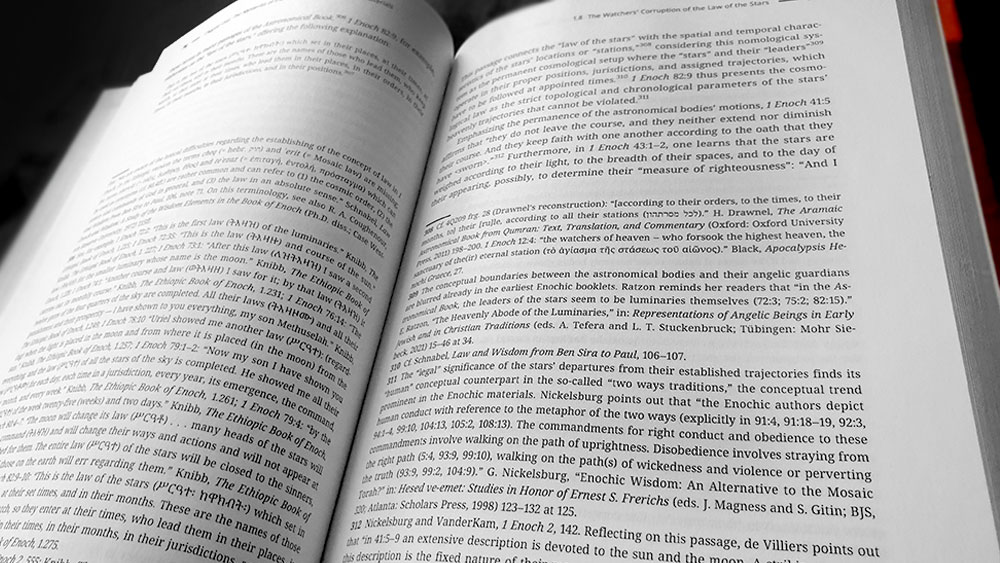

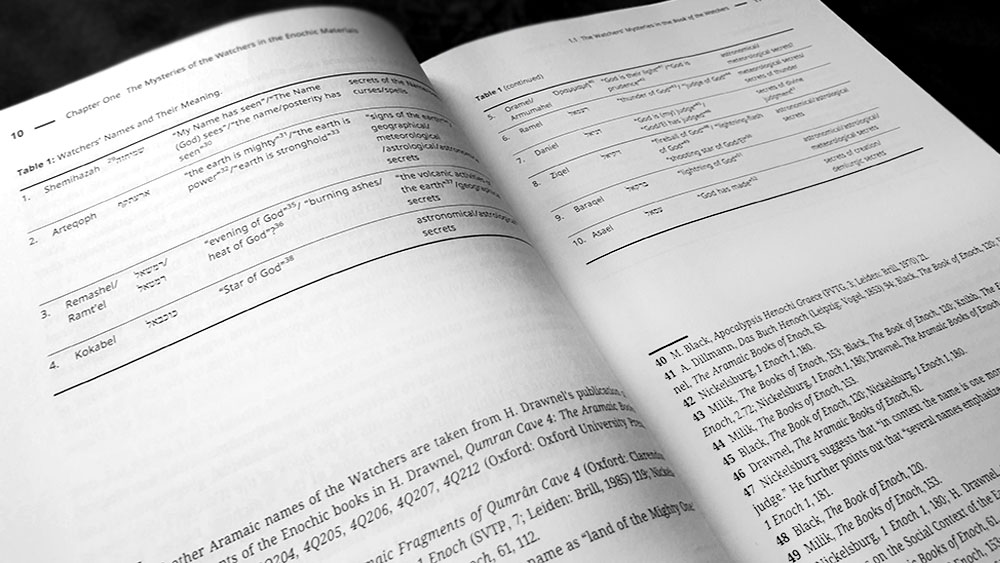

With each of these chapters considering how wisdom and the divine mysteries are treated in their respective texts, chapter one’s focus is on the role of the watchers or fallen angels as the holders and transmitters of often forbidden knowledge, as seen in the Book of the Watchers, and two other smaller Enochian booklets included in 1 Enoch, the Book of Similitudes and the Astronomical Book. Orlov shows how the watchers, prior to their fall, were closely associated with cosmological phenomena such as stars, objects whose cosmic immutability denoted a divine order and law. 1 Enoch 8:3, for example, relates that Kokabel taught the auguries of the stars, Ziqel transmitted knowledge about the signs of the shooting stars, Shamsiel unveiled the signs of the sun, and Sahriel taught the signs of the moon. Other verses from the corpus, or the etymology of their names, show the Watchers as having knowledge about matters meteorological, calendrical, geographical, elemental, and most dangerously, onomatological in regard to the divine names of God. When 1 Enoch describes how the Watchers “transgressed the word of the Lord from the covenant of heaven” it underscores how the concept of wisdom was intertwined with cosmic order, the transgression of which provides an Enochic aetiology for evil. The Watchers were not only the guardians of nomological and cosmological order, of this astronomical Torah, but the first offenders against it when they abandoned their posts, escaping from heaven with the divine knowledge.

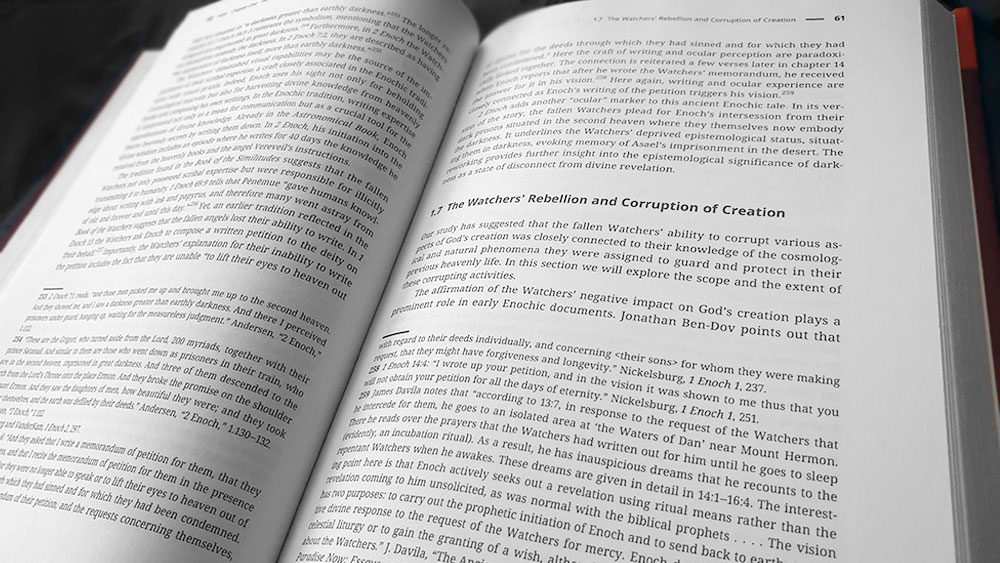

The theme of the Watchers as now disgraced custodians of divine knowledge meshes wonderfully with the role Enoch plays in Enochian literature, in which the formerly mortal patriarch is depicted being elevated to a divine status. With that apotheosis, Enoch seemingly takes over many of the past nomothetic functions of the Watchers, almost as if heaven despaired of their prior distributed-responsibility low-level employment model and found a singular, trusted upper middle management power-user more palatable. Indeed, Orlov argues throughout that the corruption caused by the Watchers’ illicit revelation of heavenly mysteries is mitigated by the way in which Enoch is given access to thematically similar clusters of secrets.

Enoch’s reception of this knowledge is not immediate like a file download or reading of a scroll, and is instead, experiential, travelling to otherworldly realms to witness the phenomena over which he is to have suzerainty. When Enoch travels through different heavens in order to view each zone’s peculiar cosmological content, Orlov argues, it suggests that such knowledge is sui generis and can only be acquired directly in these locations, via the intimate interaction with this ‘epistemological topology.’ This stands in contrast to how the same knowledge is transmitted as purely information from the Watchers to humanity, prioritising the episteme over the techne, to use the nomenclature of Greek philosophy.

Orlov spends considerable time affirming his thesis, patiently drawing each specific example from Enochic literature, and in particular emphasising the way in which Enoch’s encounters with celestial knowledge directly calls back to their former possession by the Watchers. When 1 Enoch 8 mentions the knowledge of precious stones, antimony, metals, and the roots of plants as some of the corrupting revelations giving to humans by Asael, Shemihazah and the other fallen angels, the same text later details Enoch visiting the mountains of precious stones (1 Enoch 18:6–9), the mountain of antimony (1 Enoch 18:8) and the mountains of vegetation (1 Enoch 32); whilst also receiving, in the Book of the Similitudes, a revelation about the mountains of metals. Finally, in 1 Enoch 33:2, the patriarch observes and counts the stars of heavens and the gates from which they emerged, documenting their positions, times, and months, which is then written down, including “their laws and their functions.” As Orlov argues, if the Enochic tradition sees these movements of stars and the luminaries as commandments or halakhot, then Enoch’s recording of this information is effectively copying the heavenly Torah and its halakhot, adopting a divine role that mirrors God himself, given that the Psalmists writes how “He counts the number of the stars; He calls them all by name.” (Psalm 147:4-5).

This is an extensive chapter that goes well beyond what is covered in the summary here, and is indicative of Orlov’s approach throughout the book. He uses the theme of celestial wisdom to present a thorough image of Enoch’s role within divine order, and the increasingly important responsibilities he was given, rising inexorably until in 3 Enoch he ultimately became, as the angel Metatron, the very voice of God. Orlov credits Enoch’s reception of celestial knowledge as the fundamental catalyst for this ontological metamorphosis, with the transformative nature of the law of the stars endowing the patriarch with a new celestial identity and an otherworldly nature, including omniscience. Conversely, the Watchers, in abandoning their posts as caretakers of the divine wisdom, lose their divinity, with the acquisition and dispersal of divine knowledge closely corresponding to specific vectors of topological progression: upwards for Enoch, downwards for the fallen Watchers.

In his final chapter, The Mysteries of Enoch in 2 Enoch and 3 Enoch, Orlov continues his exploration of Enoch as an elevated celestial figure, particularly in regard to his soteriological role, which in both 2 Enoch and 3 Enoch is further enhanced with new otherworldly features. This is particularly true of 3 Enoch, also known as Sefer Hekhalot and The Elevation of Metatron, which, as one of its titles conveys, documents Enoch transmogrification into the King of the Angels, as The Zohar calls him, Metatron. Orlov draws attention to the soteriological role of Enoch/Metatron as someone who then transmits, with full divine permission, the wisdom and torah of the stars to humanity. This Enochic Torah differs from the Mosaic Torah, particularly in the latter’s rigid spatial ideology, as demonstrated by the scriptural aversion to having protagonists travel to heaven to receive revelation as Enoch does: Moses ascends only the earthly Mt. Sinai when he receives the law, and Ezekiel experiences his vision of the Merkavah, not in heaven but beside the river Chebar. 3 Enoch does bridge this gap, though, combining the two torah when it describes Metatron as the one who transmitted it to Moses, bringing it out from God’s storehouses and giving it to Moses. It then lists the Torah’s traditionally given Mishnaic chain of descent that continues to Joshua, the Elders, the Prophets, and the Men of the Great Synagogue, but ends with two final groups of recipients, the unspecified Men of Faith and in turn, the Faithful.

Orlov is always a joy to read, with his casually comprehensive knowledge of his sources facilitating a convincing, internally coherent thesis. As with other Orlov titles, he goes crazy with the footnotes, featuring not just citations but entire, sometimes multiple paragraph, notes that can stretch to almost a full page; making reading the main body a brisk page turner in places.

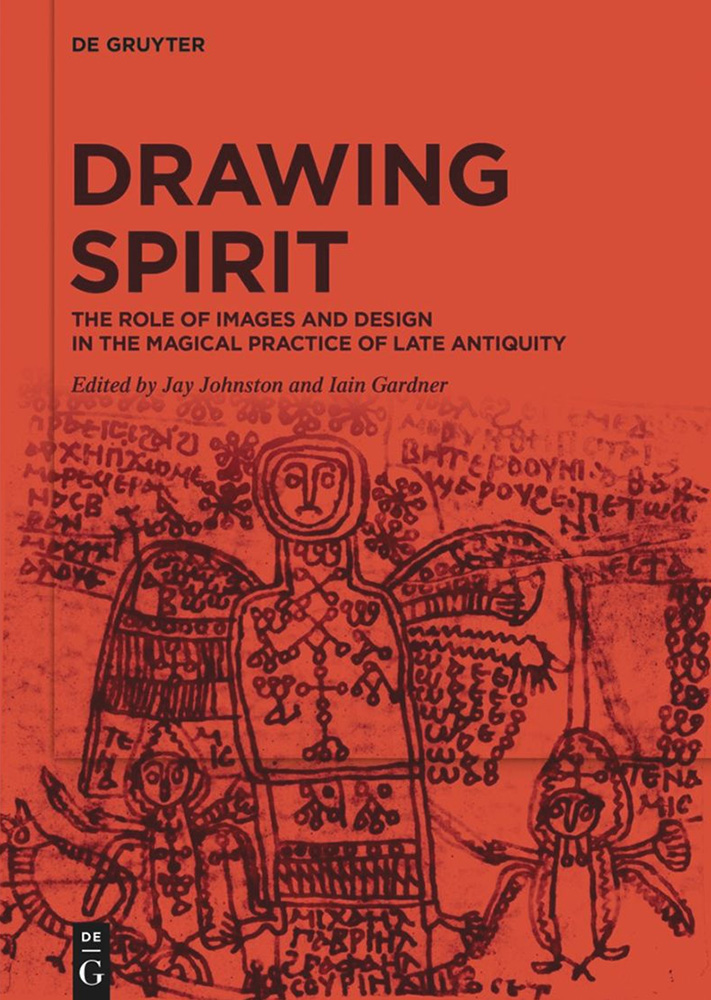

Published by de Gruyter