Jan Machielsen’s The War on Witchcraft is part of Cambridge University Press’ compact Elements in Magic series, which aims to restore the study of magic to a central place within culture. A brief work, it has an ambiguous title with a far more informative subtitle of Andrew Dickson White, George Lincoln Burr, and the Origins of Witchcraft Historiography. The two American historians of the title, Machielsen argues, have had a little acknowledged but lasting influence on the field of modern witch hunt studies, one that is comparable, if in opposition, to the more familiar, and slightly later, Margaret Murray and Montague Summers. Machielsen’s work has its origins in 2010 when, as a graduate student, he received a scholarship to Cornell University, giving him the opportunity to study its large witchcraft collection (begun by one of Cornell’s founders, the aforementioned Andrew Dickson White), thereby sparking an interest in the library’s origins. The text itself began life in 2016 as a lengthy article, before enduring, as Machielsen wryly reflects, three years of rejections from a trio of academic journals, until he was encouraged by Alex Wright and Elements in Magic series editor Marion Gibson to expand it into its final form during a research stay in Germany, funded by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Jan Machielsen’s The War on Witchcraft is part of Cambridge University Press’ compact Elements in Magic series, which aims to restore the study of magic to a central place within culture. A brief work, it has an ambiguous title with a far more informative subtitle of Andrew Dickson White, George Lincoln Burr, and the Origins of Witchcraft Historiography. The two American historians of the title, Machielsen argues, have had a little acknowledged but lasting influence on the field of modern witch hunt studies, one that is comparable, if in opposition, to the more familiar, and slightly later, Margaret Murray and Montague Summers. Machielsen’s work has its origins in 2010 when, as a graduate student, he received a scholarship to Cornell University, giving him the opportunity to study its large witchcraft collection (begun by one of Cornell’s founders, the aforementioned Andrew Dickson White), thereby sparking an interest in the library’s origins. The text itself began life in 2016 as a lengthy article, before enduring, as Machielsen wryly reflects, three years of rejections from a trio of academic journals, until he was encouraged by Alex Wright and Elements in Magic series editor Marion Gibson to expand it into its final form during a research stay in Germany, funded by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Machielsen begins with a brief but comprehensive review of eighteenth century scholarship’s rational approach to witchcraft which sought to dismiss allegations against witches as an embarrassing and superstitious delusion, now safely and mercifully consigned, in the clear light of modernity’s day, to the past. It is this academic, historiographical onslaught, continued by White and Burr, which is the war of the book’s title and a play on White’s voluminous A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom. As Machielsen notes, such eighteenth century scholarly attitudes were fundamentally paternalistic and condescending, comparable to that of the very demonologists and church authorities that scholars now sought to denigrate, men whose appeals to a greater sapient authority, framed within the certainty provided by an absolute dichotomy of true and false, was later mirrored by scholarship’s belief in an axiomatic rationality set against equally self-evident irrationality. Just as demonologists used the language of superstition, dressed up in religious nomenclature, so academia defined both belief in witchcraft and the witch hunts that followed as thoroughly superstitious, as inherently irrational and therefore belonging to the past. In the early 1900s, Murray and Summers, who could both be, and were, dismissed as enthusiastic amateurs, took a different approach, with Murray positing that early modern Europe’s witches had been members of a secret pagan fertility cult, while the Catholic convert Summers argued for a literal and perennial worship of demons with the witch as a “minister to vice and inconceivable corruption” and “a member of a powerful secret organisation inimical to Church and State.”

The work of Andrew Dickson White and his student George Lincoln Burr is positioned here in opposition to the literalism later embraced by Murray and Summers, being a continuation of the veneration of the rational that sought to consign witchcraft to history. In some ways, this was merely an adjunct of White core and overstated thesis, as explored in A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom, in which dogmatic theology and science were, and had forever been, inimical to each other, locked in perpetual and fundamental conflict. White drew attention, for example, to the way in which his rational heroes, be they scientists, witchcraft sceptics, or even printers, were pilloried with allegations of sorcery by an irrational world, such as the thirteenth-century physician Arnold de Villanova (charged with sorcery and dealings with the devil) or England’s first printer, William Caxton (who did not escape the charge of sorcery). The war on witchcraft and the warfare of science were, thus, effectively extensions of each other, with the witch-hunt being emblematic of the consequences of dangerous theological and sectarian ideas. That isn’t to say that White’s embracing of unassailable rationality extending to dismissing Christian belief itself and it was his opposition to inhibitive theology, rather than Christianity itself, that allowed him to see himself as, in the words of Machielsen, “the latest (if not the last) in a long line of virtuous Christian men fighting for scientific and religious Truth.”

It was White’s student, Burr, who ran specifically with these themes of witchcraft, sharing a philosophy with his mentor that any form of false belief existed only to be refuted as the absence or corruption of something good. Burr’s language spoke to this with earnest zeal, seeing witchcraft as a ‘nightmare of Christian thought,’ a pale and perverse shadow of the real thing that was to be exposed in the light of rational day by heroic and devout men. While ideas of witchcraft as female, irrational and hysterical underlie their work, the paternalistic misogyny and hyper masculinity of White and Burr meant that the female role in the witch craze was simultaneously promoted and minimised, with, as Machielsen notes, both men seeing the witch-hunt as a battle between two types of male elites. Its cast of rival masculinities featured those who believed in the phenomenon, while their critics were perceived, by them, to be motivated solely by a desire to undermine their position of power; the female victims and their condition being completely superfluous to this patristic battle for supremacy. Such an essentialist viewpoint simultaneously made the prospect of a male witch a problematic anomaly, given that such a person lacked agency of the heroic male variety. Thus, in Burr’s work, Johannes Junius (mayor of Bamberg executed for witchcraft in 1628) and Dietrich Flade (university rector and electoral judge executed for sorcery in the Trier witch trials) are positioned solely as heroic witchcraft sceptics and righteous opponents of the hunt, with any prospect that the accusations could have had some foundation being completely ignored.

Machielsen suggests that such a view point had a lasting legacy on witchcraft historiography and contributed to the minimising, by both sceptical scholars and feminist revivalists, of the role of male witches within the historical record. In his conclusion, Machielsen also notes how witch-hunt studies in the vein of White and Burr shore up the perennial appeal of the warfare thesis in which it is comforting to glibly see history as a heroic and inexorable march of progress that defines itself in opposition to the theological missteps that it hopes to have relegated to the past, but which still threatens to burst through the blurred temporal boundaries.

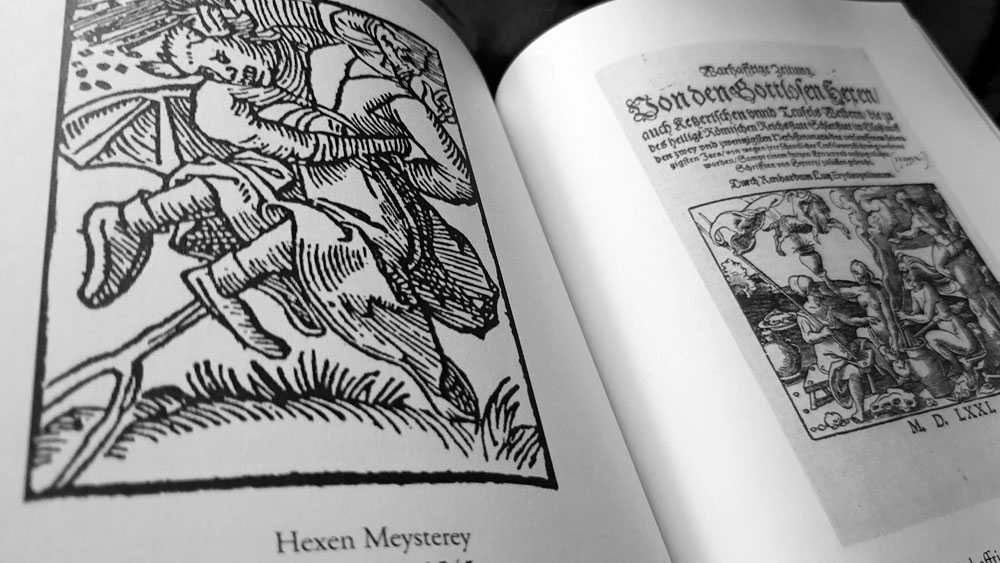

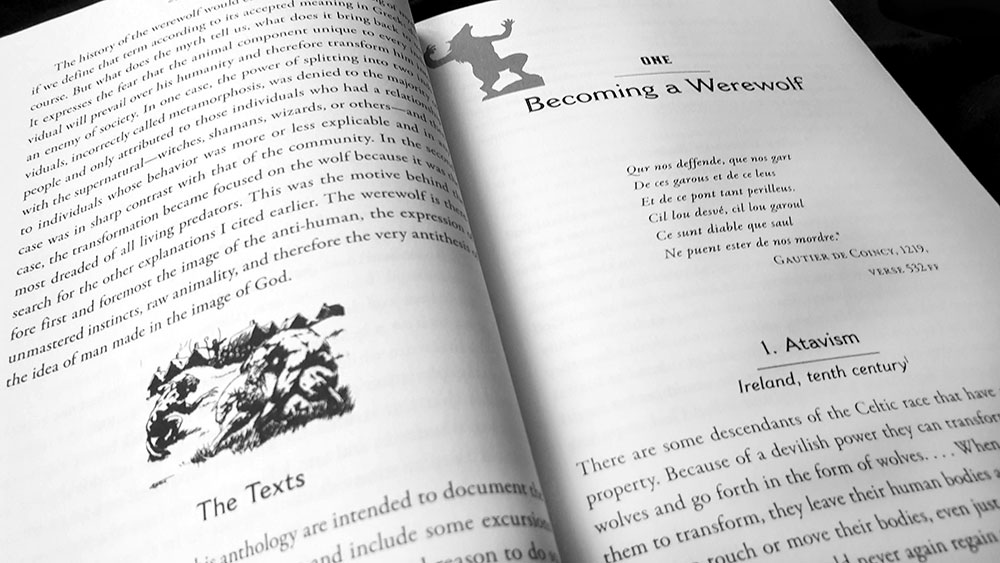

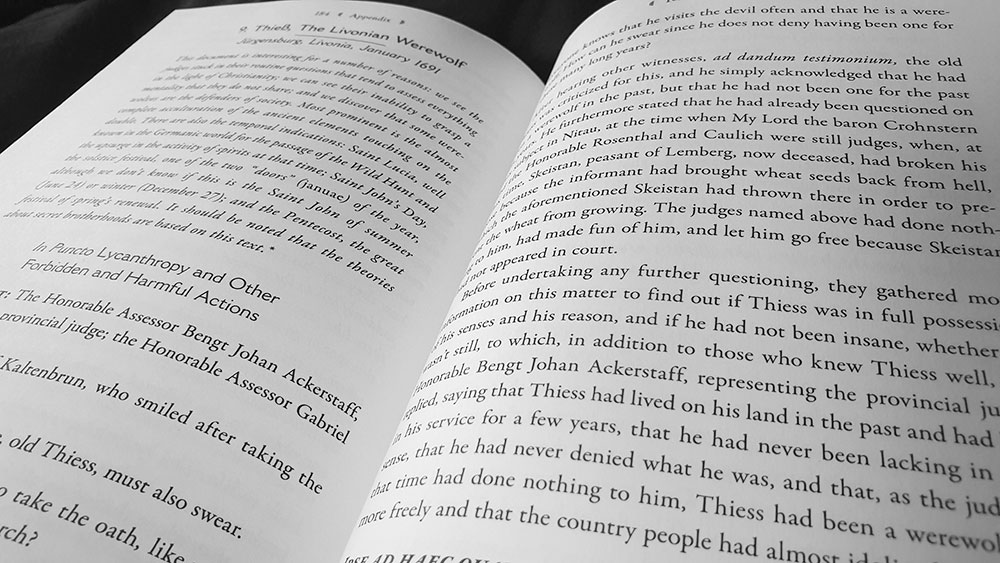

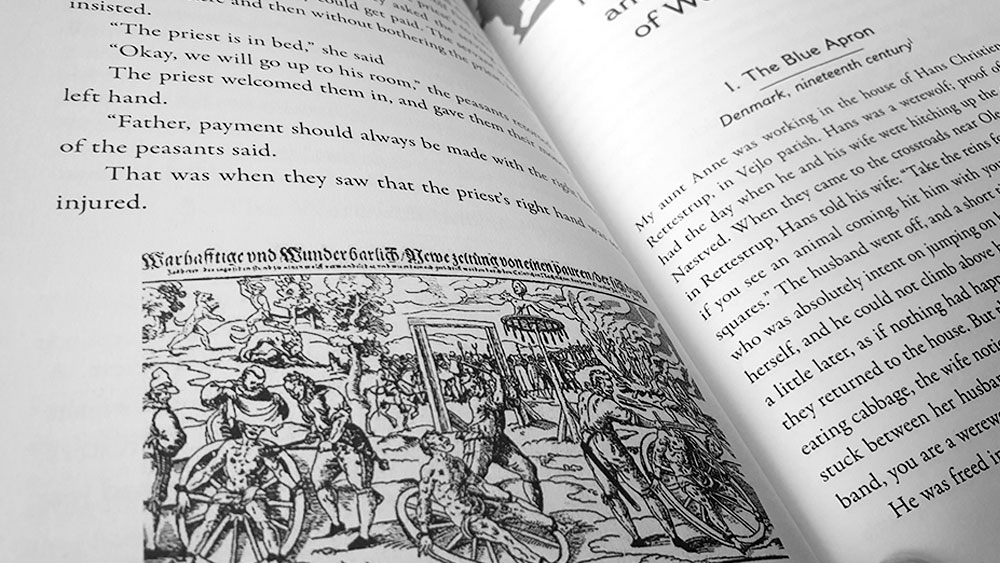

The War on Witchcraft is basic in its formatting, the body set in a standard serif, exhaustive footnotes tidily footnoted, with the occasional image sprinkled throughout. Everything is purely functional, right down to the lack of new chapter pages, with each chapter flowing through on the page, separated only by a title in an aberrant blue typeface. As a concise history of the thoughts of two men, The War on Witchcraft is a joy to read, providing an insight little available elsewhere.

Published by Cambridge University Press