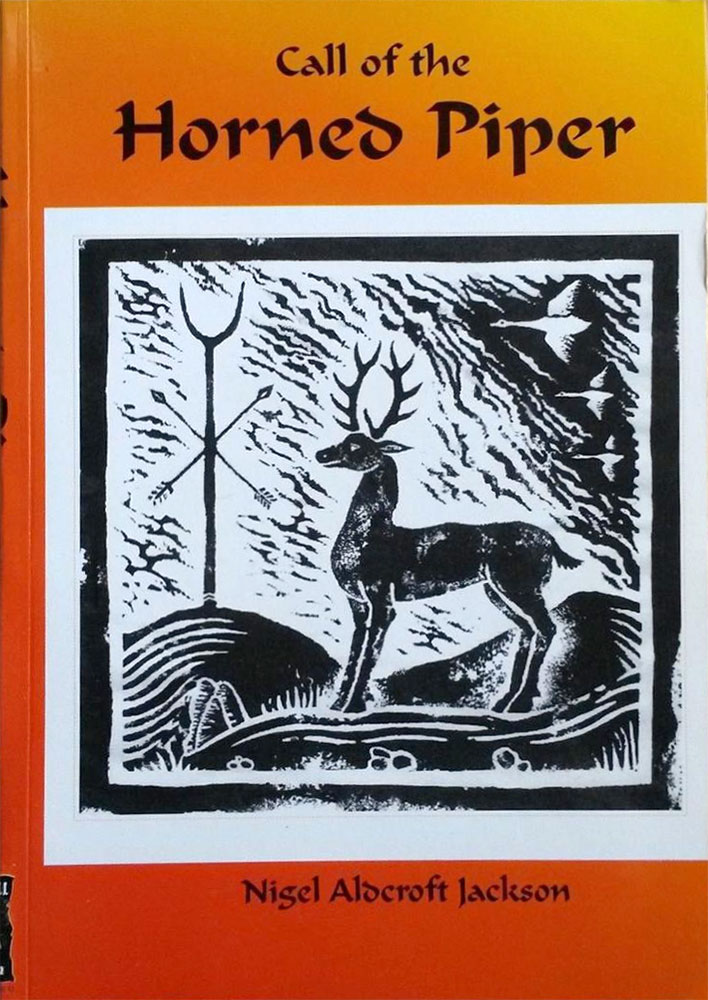

It is sometimes hard to keep track of the various Nigel Jackson, Michael Howard and Evan John Jones titles released on Capall Bann. There’s not a lot of them necessarily, but the titles are somewhat interchangeable, and the covers are similar, if not in style then at least in theme (you’d better believe there’ll be horns on there). That’s not a criticism per se, simply a recognition that Jackson and his colleagues mine a very particular seam

It is sometimes hard to keep track of the various Nigel Jackson, Michael Howard and Evan John Jones titles released on Capall Bann. There’s not a lot of them necessarily, but the titles are somewhat interchangeable, and the covers are similar, if not in style then at least in theme (you’d better believe there’ll be horns on there). That’s not a criticism per se, simply a recognition that Jackson and his colleagues mine a very particular seam

After struggling through a fair amount of poor occult writing, where authors either can’t write or overreach whilst trying to sound more esoteric or more academic, reading Jackson here is something of a relief. Sure, he habitually types ‘it’s’ when he means ‘its’ but besides that most unforgivable of sins, he can actually write, creating a flowing narrative that is easy to read and at the same time, sophisticated and erudite. In some instances, he shows a particularly refined ability for the picturesque, with the first chapter beginning with a theoretical scenario of a witch preparing for transvection, written in a beautifully descriptive way.

In other instances though, as is the style of the book, Jackson just presents information in something of a fact-dump manner; albeit still well written. This kind of data (instances of witch accounts or folklore examples for the most part), will be largely familiar to anyone from these circles of traditional craft, which may be why there’s such a dearth of citing of sources. While the common knowledge nature of these facts makes this lacking of references slightly forgivable, one does find little gems that makes one wish for a place to go for more information – like the brief remark that Swedish witches preferred to use magpie forms when shapeshifting…. oooh, tell me more.

Call of the Horned Piper is divided into short, unnumbered chapters addressing various witchcraft themes, and these are grouped in the contents section into broad, unnamed segments that the reader won’t necessarily notice when reading the book from start to finish. In the first, Jackson considers what one could define as the sabbat and the wild hunt, emphasising the goddess lead versions of the Heljagd under Holda, Hela and Herodias, before moving on to her male counterpart, the Horned Master. This acts as a fulfilment of a statement of intent that Jackson makes at the start of the book, placing the witch’s ride at the centre of the image of the witch, with the broomstick being the preeminent symbol of this topology. By drawing together myriad threads provided by sabbat transvection and various other supernatural journeys, taken by either practitioners or deities, Jackson highlights the way in which this shamanic mystery with thousands of years of provenance lies at the core of Traditional Craft.

Later, Jackson incorporates other far flung strands of folklore, such as even werewolves and vampirism, showing how, in the footsteps of Carlo Ginzburg and Éva Pócs, these seemingly less esoteric aspects of legend play into the image of supernatural, shamanic-style journeys. Indeed, one could say that Jackson provides an entry level version of theories by Ginzburg, Pócs and the later Emma Wilby, heavy on examples but light on detail, and from a more hands-on, personally involved and less academic perspective.

Jackson concludes Call of the Horned Piper with a practical section, providing information on tools and hallowing the witches compass, as well as a guided visualisation, Mysterium Sabbati: Riding on the Witch Way. There’s not a lot here but as a core toolkit it suffices and the theory and lore that precedes it contains enough information for practitioners to fill in the gaps and develop their own rituals in a Traditional Craft mould.

In all, Call of the Horned Piper has much to recommend it. It contains a wealth of information that can lead to more indepth investigation when you track down the uncited sources, and it comes from a specifically endemic place, with Jackson clearly providing the bones to existing modalities. Of specific personal appeal is the way in which Hela appears throughout the book, particularly in Her guises as a witch goddess of the underworld, with Jackson making several references to her.

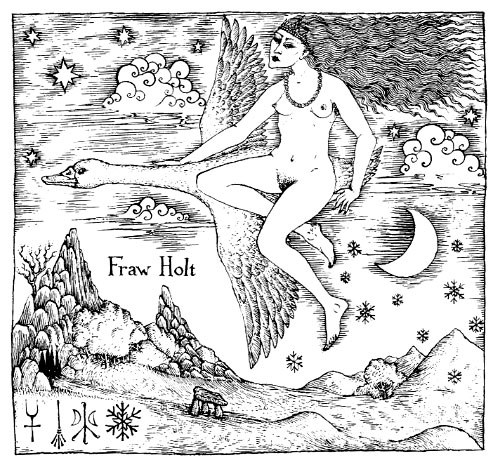

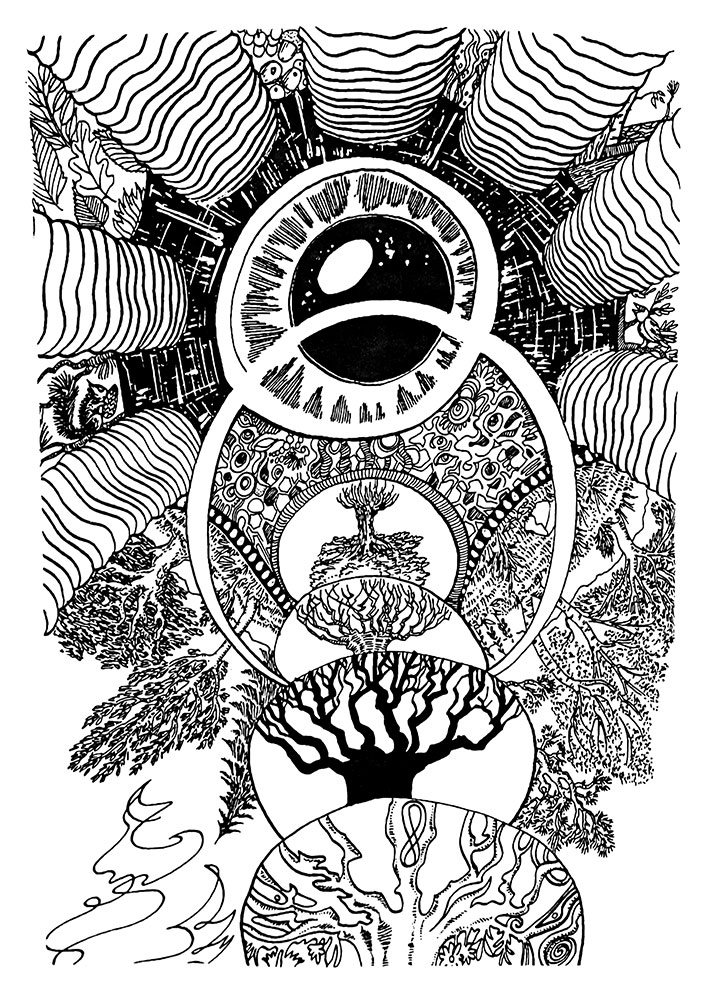

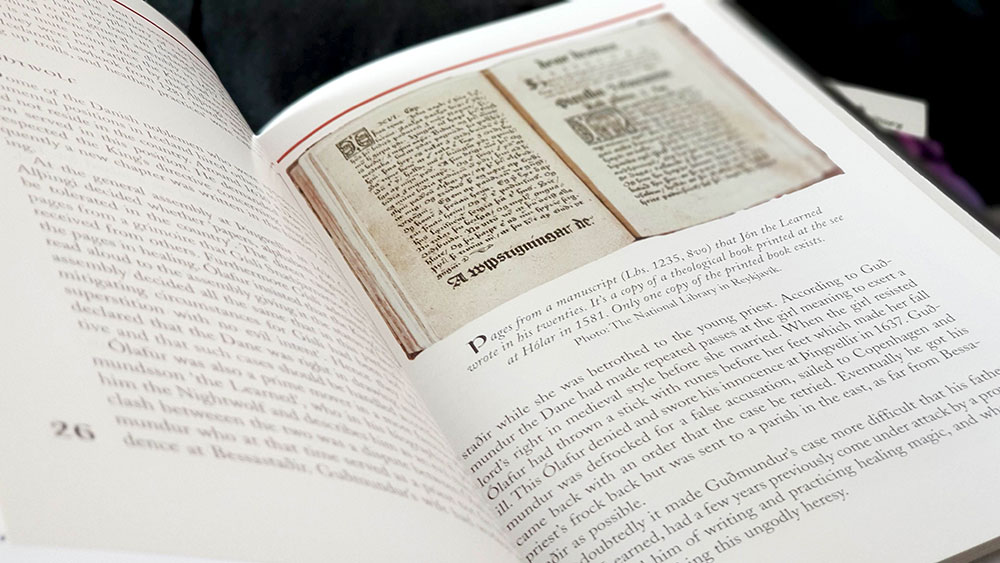

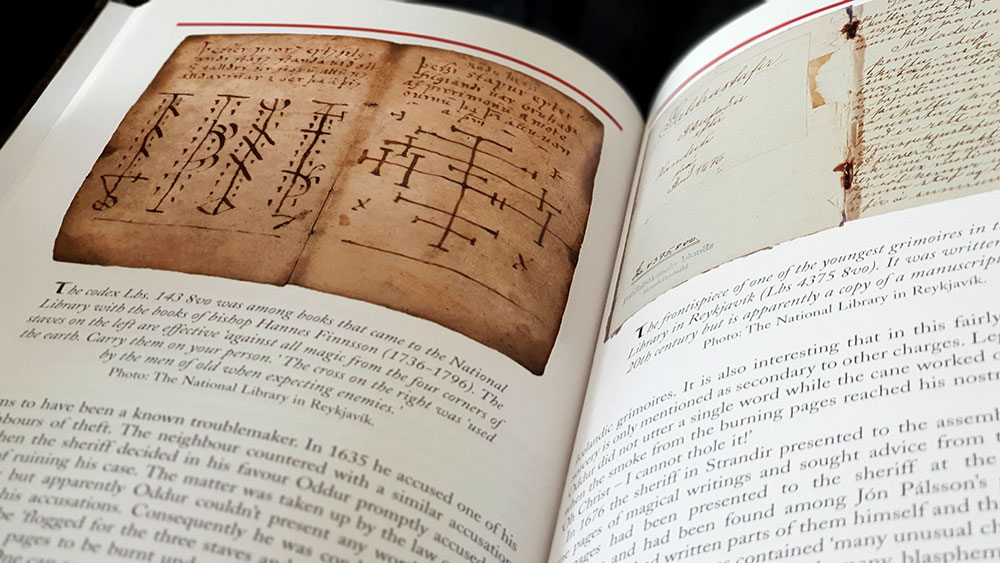

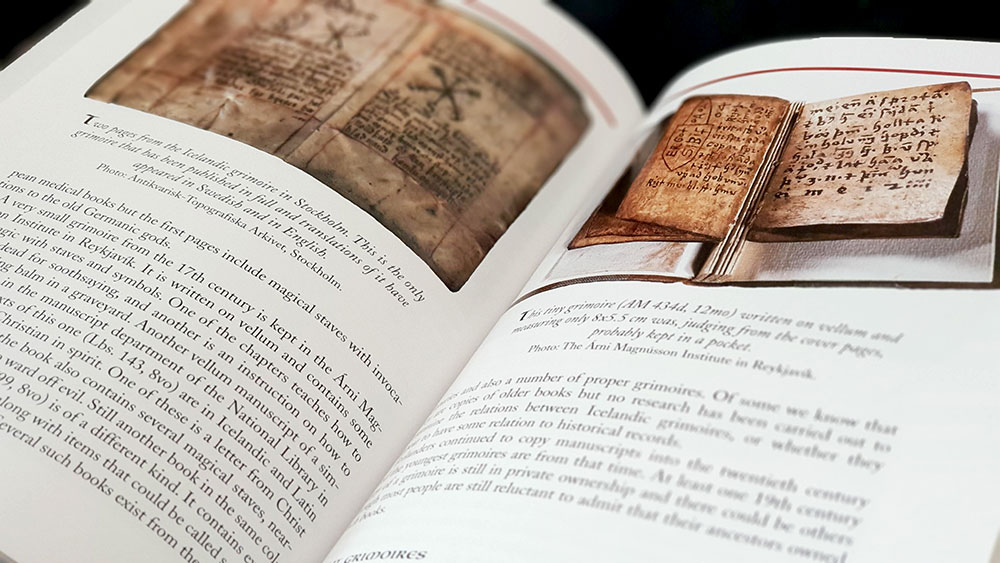

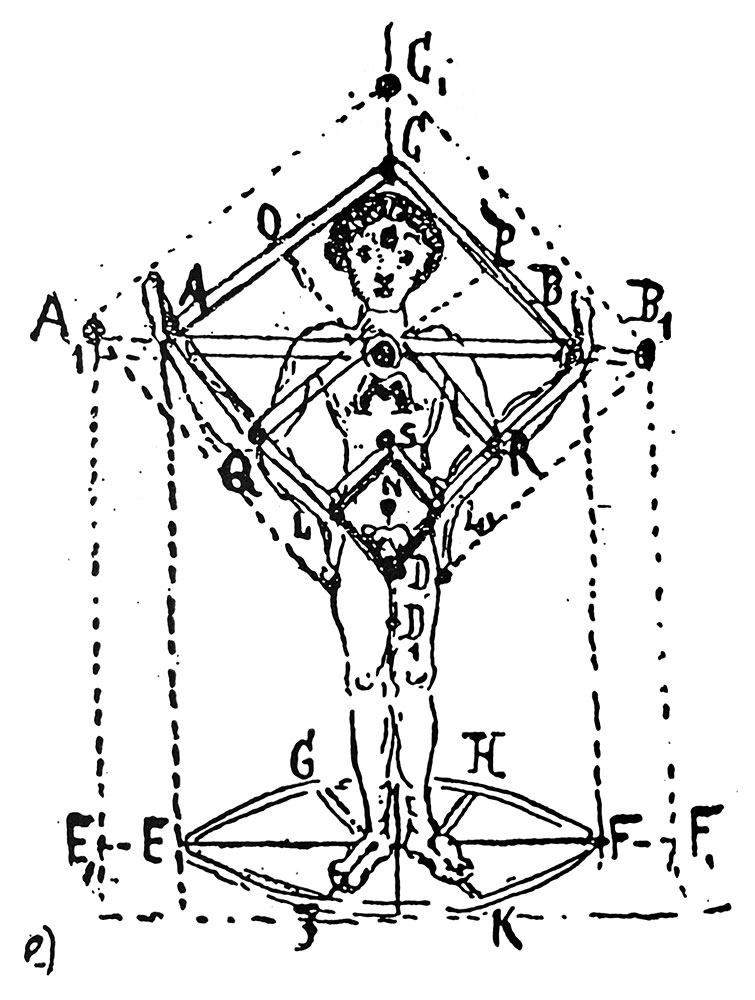

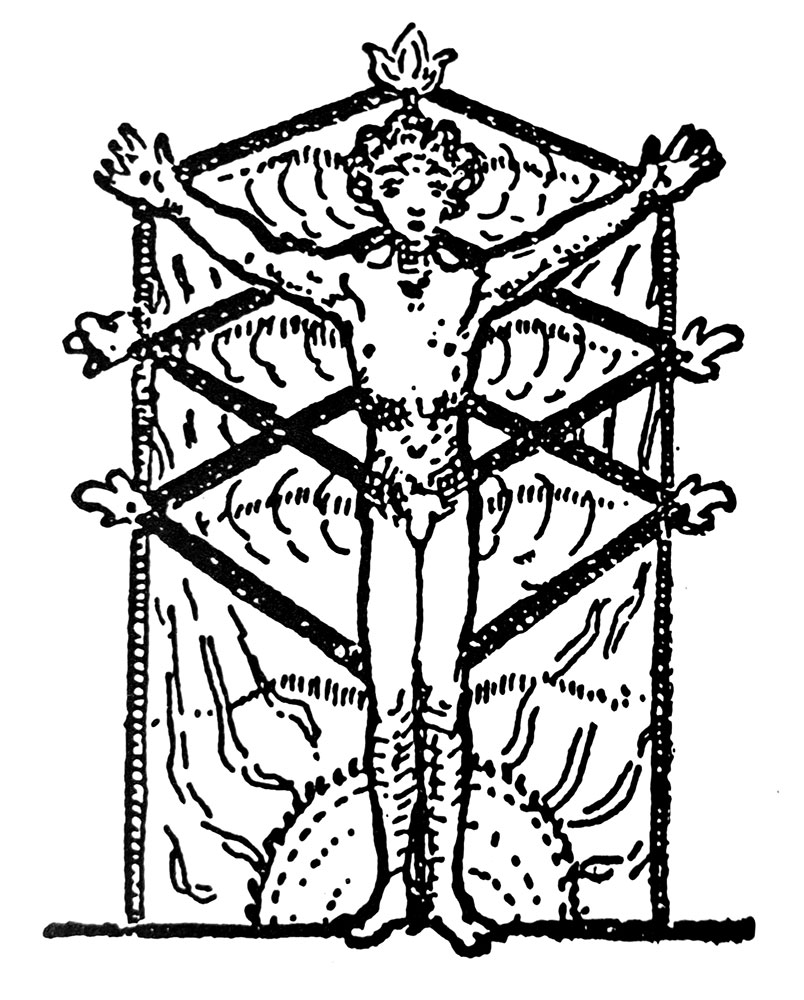

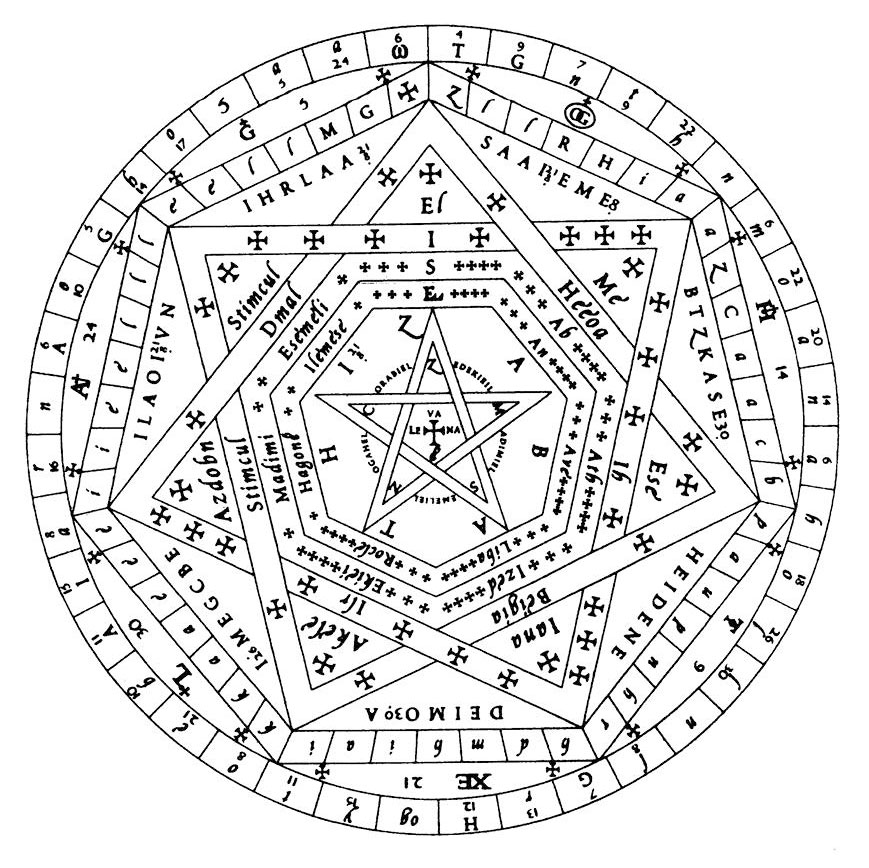

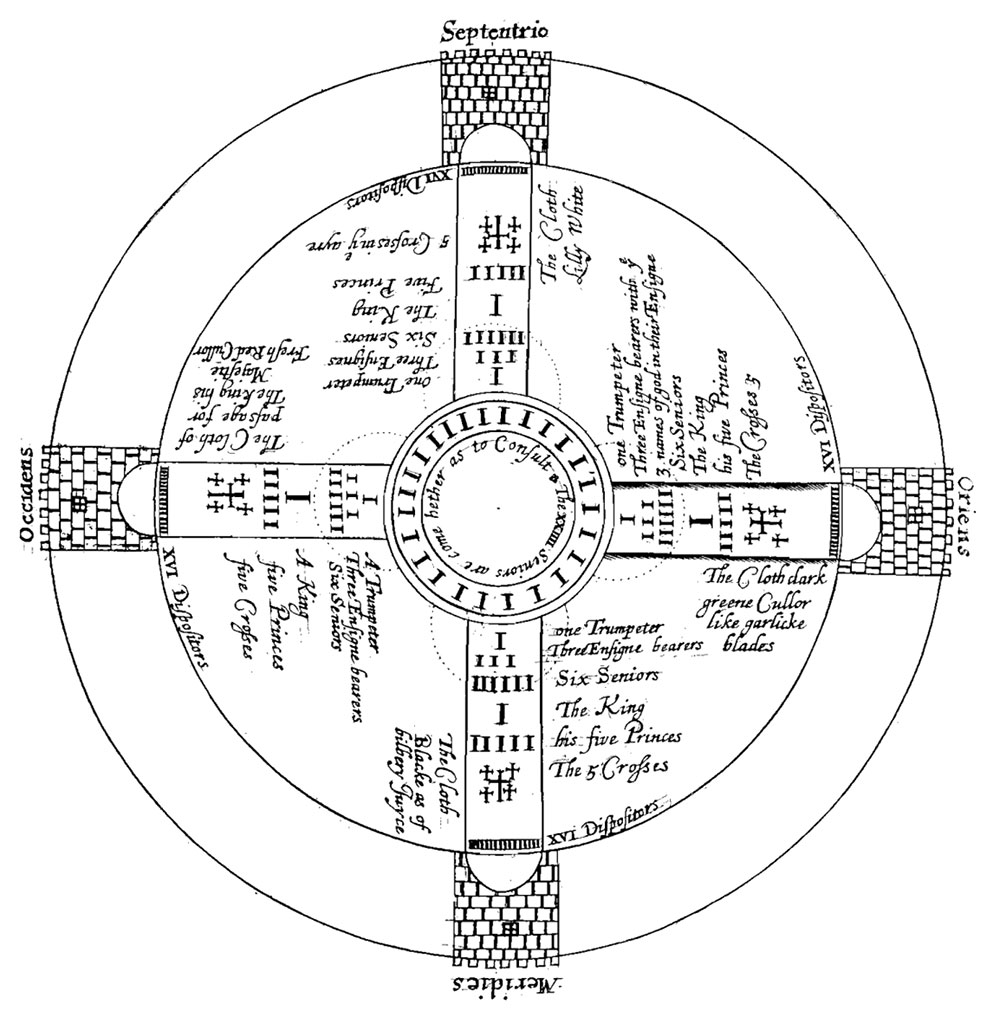

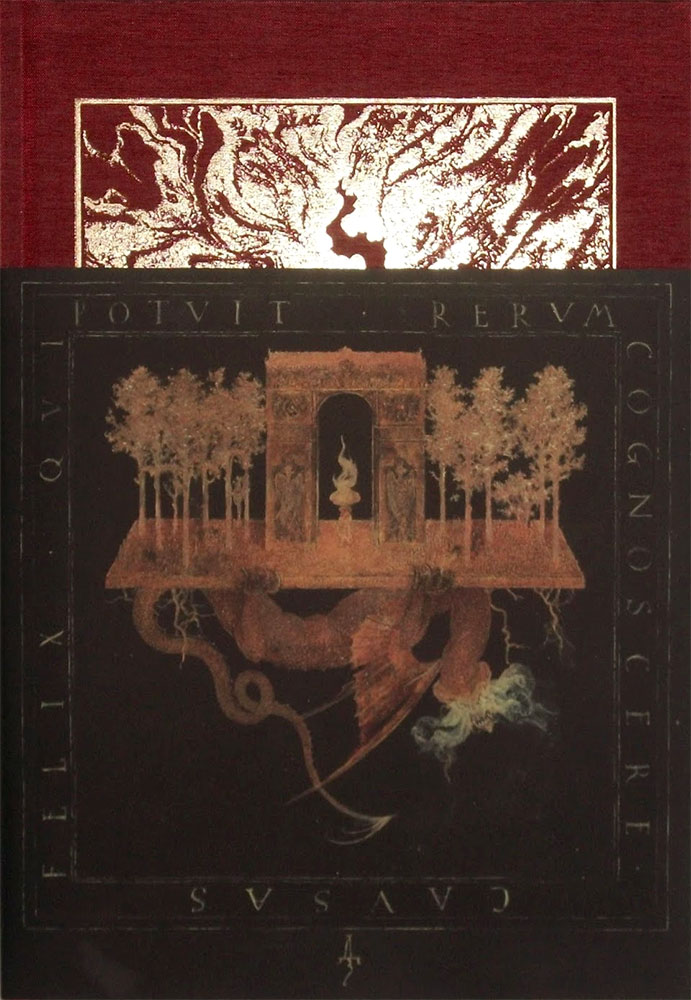

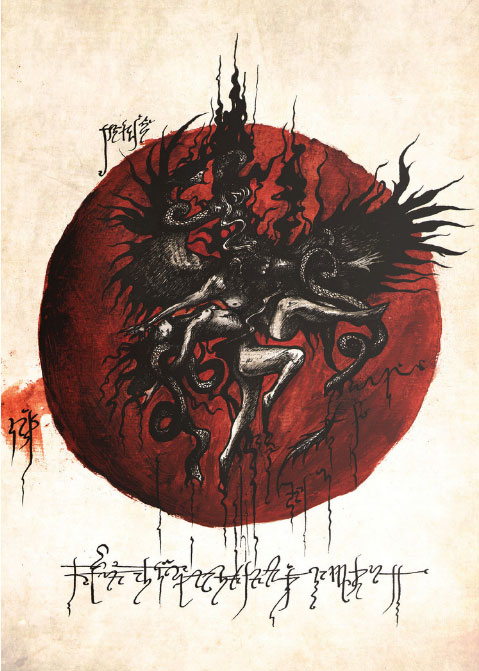

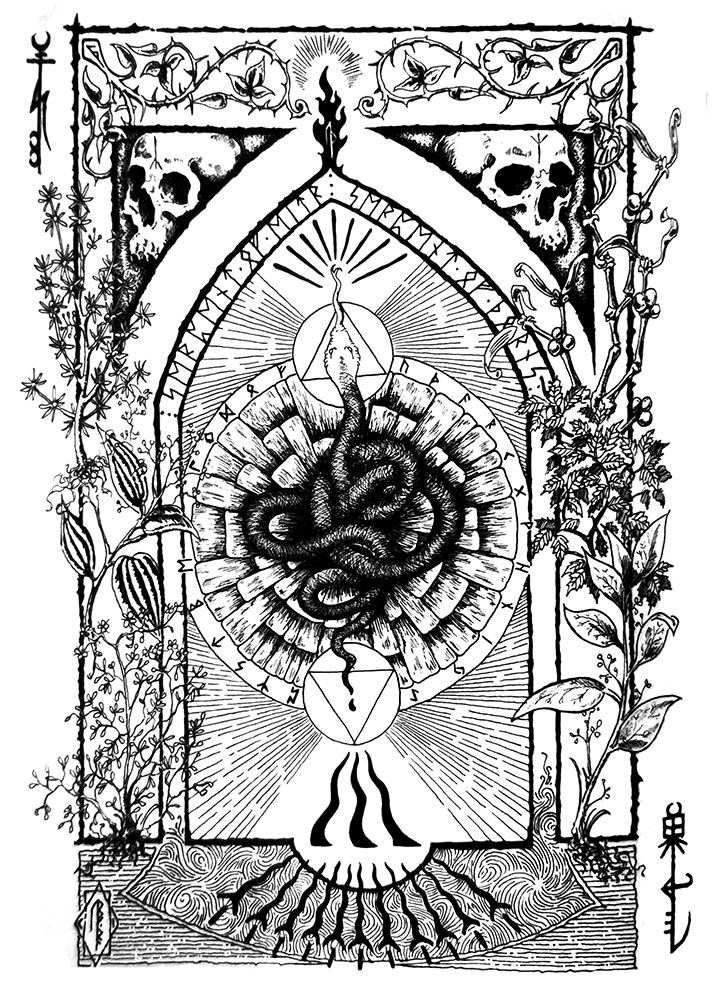

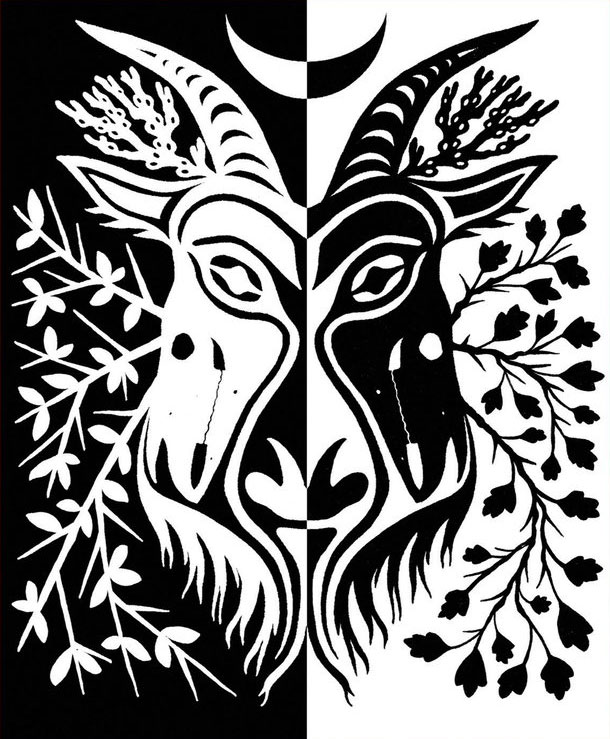

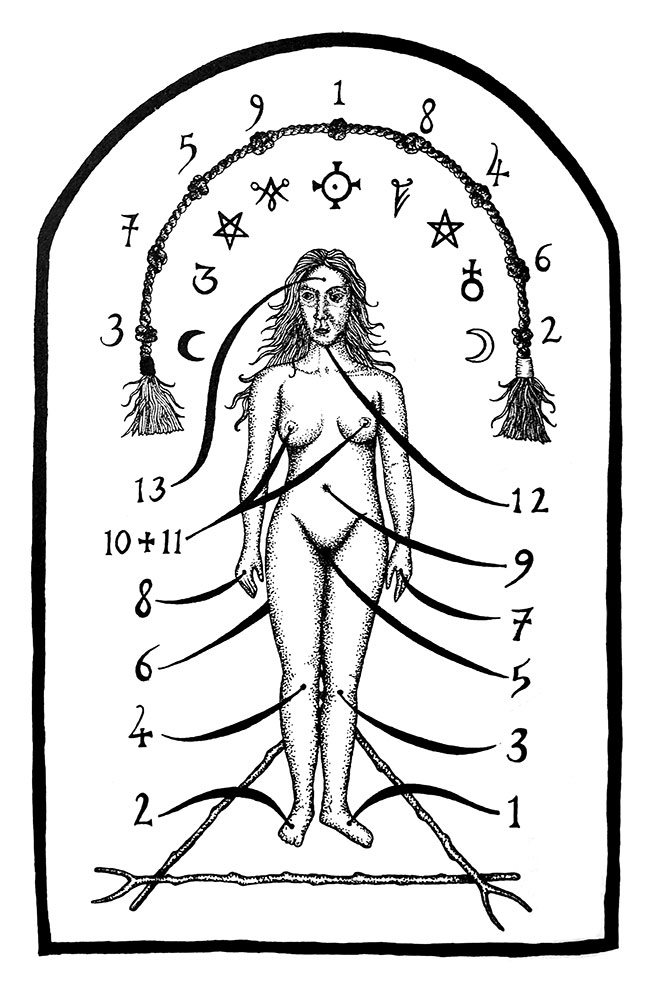

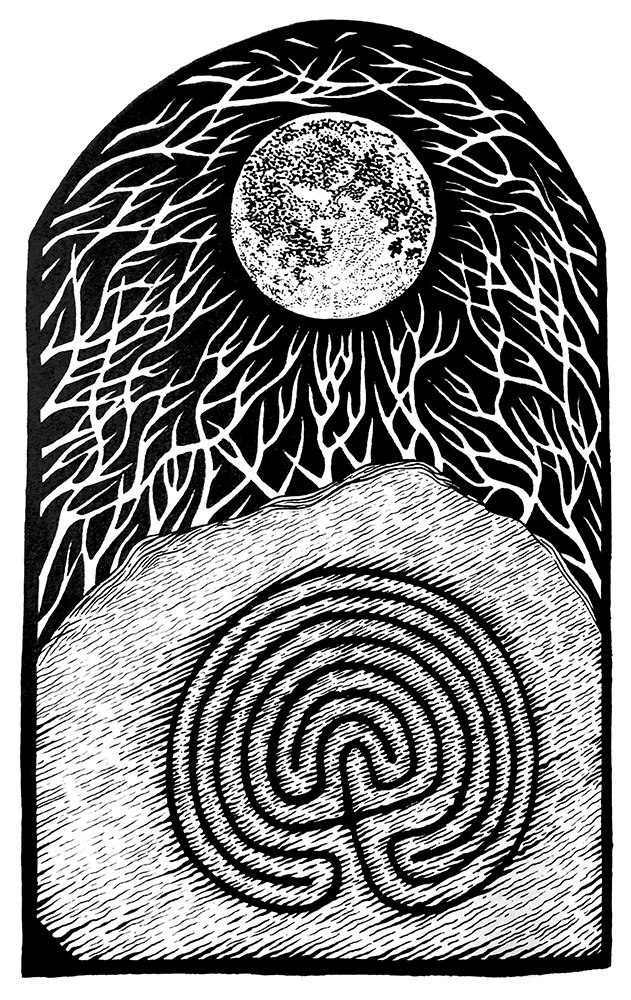

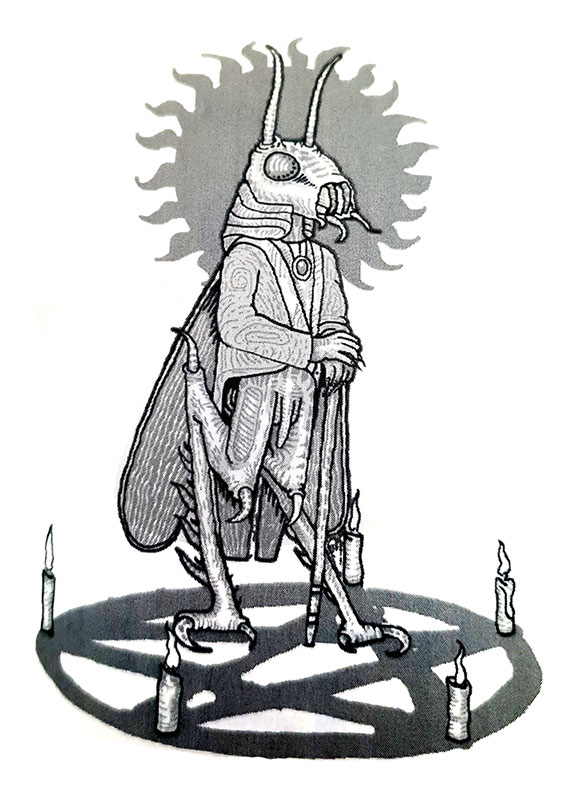

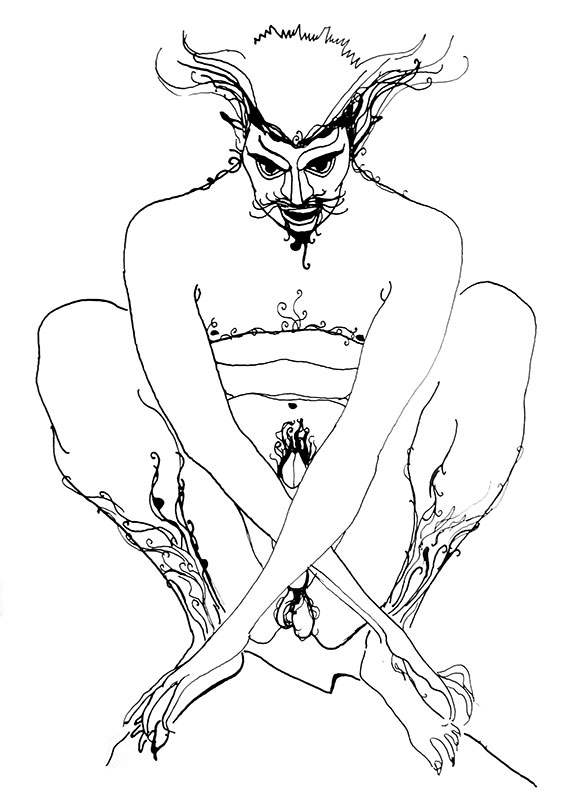

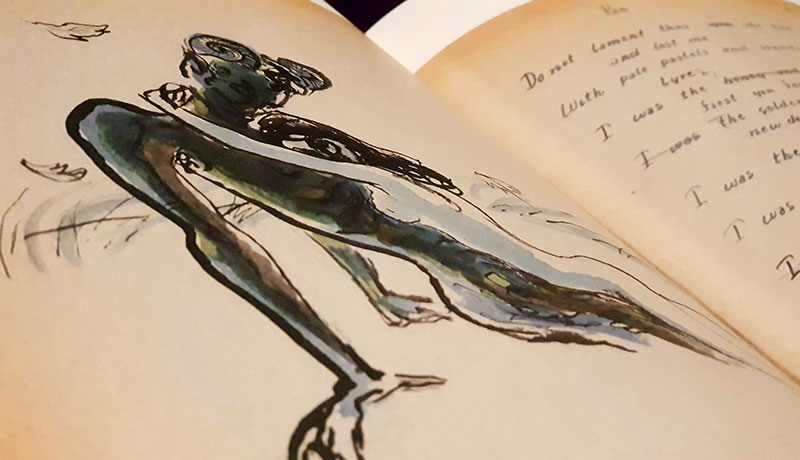

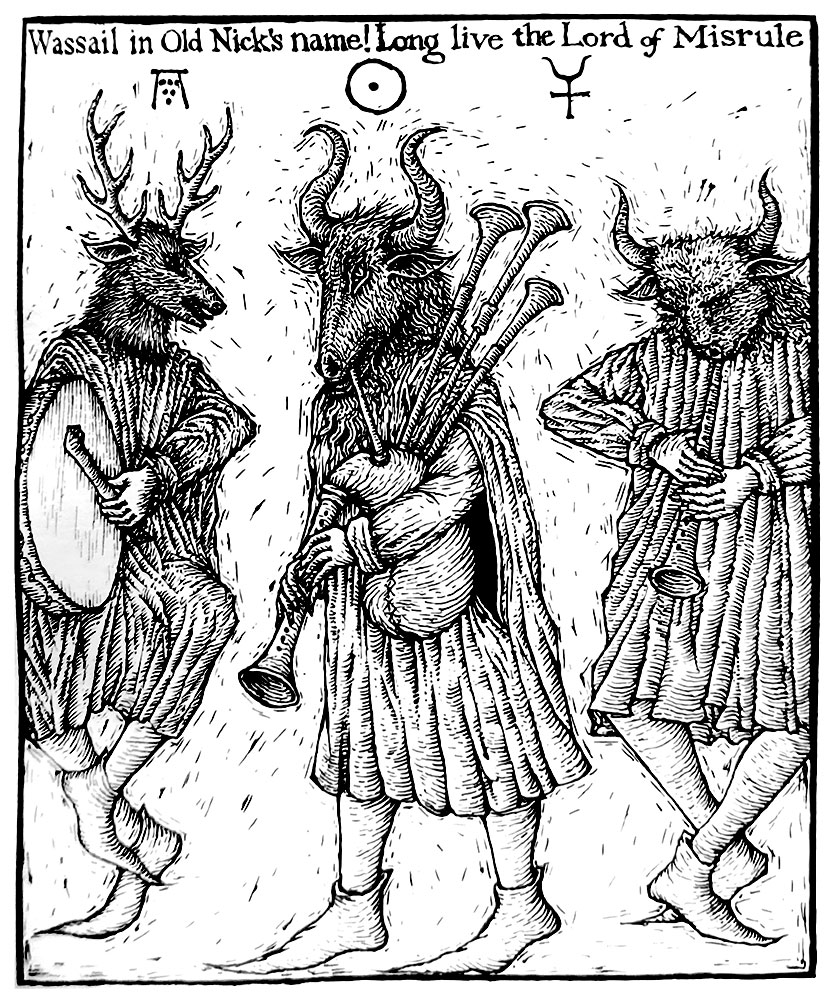

Call of the Horned Piper is illustrated throughout by Jackson himself, which, as Gemma Gary does in her books, adds an additional layer of interest, omneity and authenticity. Jackson employs a variety of styles, largely differentiated by the weight of stroke. There’s woodcut (or woodcut-styled, it’s hard to tell) images, high in contrast as is the nature of the medium, and then there’s detailed, fine-line ink drawings. While there’s a certain rustic charm to the woodcuts (and I’m particularly fond of the image of Hela), it is their more intricate siblings that really appeal. These recall some of the work of Andrew Chumbley or Daniel Schulke, with icons that are beautifully archaic, festooned with hand written text and more mystical sigils than you can shake a stick at. Unfortunately, their effectiveness is lessened by repeated use, with some of the images reappearing throughout the book at various sizes as unnecessary fillers. Jackson’s fine line pictures also include more illustrative images, such as his stunning Fraw Holt, which I recall on the cover of an issue of The Cauldron so many years ago. In these, Jackson renders fey figures with an imperial distance and acerose features, in a timeless, evocative style that seems weighted with meaning.

The, how you say, roughness of Capall Bann productions has been noted before here at Scriptus Recensera, and Call of the Horned Piper is no exception. The book title on the spine is so large that it seeps onto the front and back covers, as does the Capall Bann logo, while the title on the cover is off-centre. The typeface choice and treatment on the cover leaves something to be desired, as does the orange gradient, which makes the book look prematurely sun faded. The image on the front, a striking woodcut by Jackson, is treated unsympathetically, askew within an unattractive white frame, with a dotted magenta trim line visible around the edge for some reason.

Published by Capall Bann