Gabriel McCaughry’s (h)Auroræ could be considered an inadvisable tome to review here at Scriptus Recensera because attentive readers will note that your faithful reviewer has a proofing credit in the opening pages. In my defence, your honour, the proofing was for only a section of the work, and the finished book is so much more, appearing unfamiliar and unrecognisable from the raw and partial pure-text draught I worked with; unless that’s just due to a poor memory… I don’t remember.

Gabriel McCaughry’s (h)Auroræ could be considered an inadvisable tome to review here at Scriptus Recensera because attentive readers will note that your faithful reviewer has a proofing credit in the opening pages. In my defence, your honour, the proofing was for only a section of the work, and the finished book is so much more, appearing unfamiliar and unrecognisable from the raw and partial pure-text draught I worked with; unless that’s just due to a poor memory… I don’t remember.

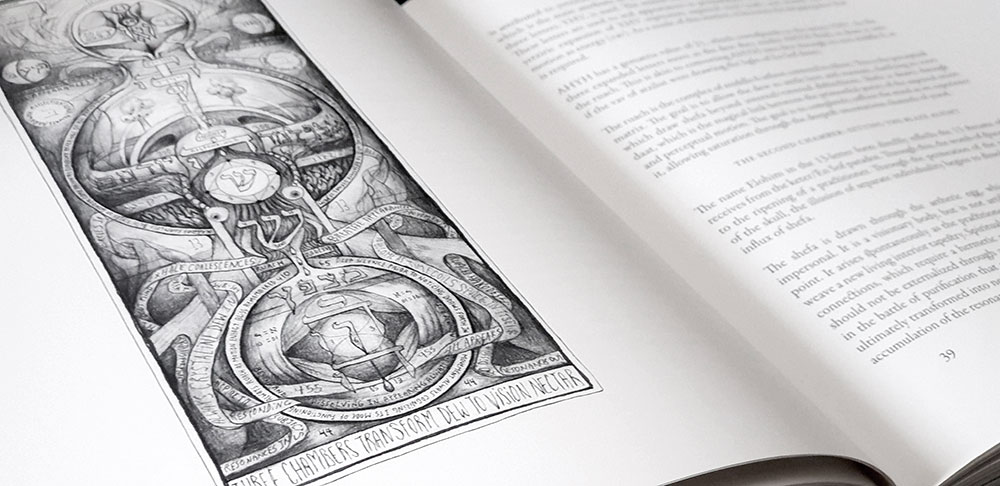

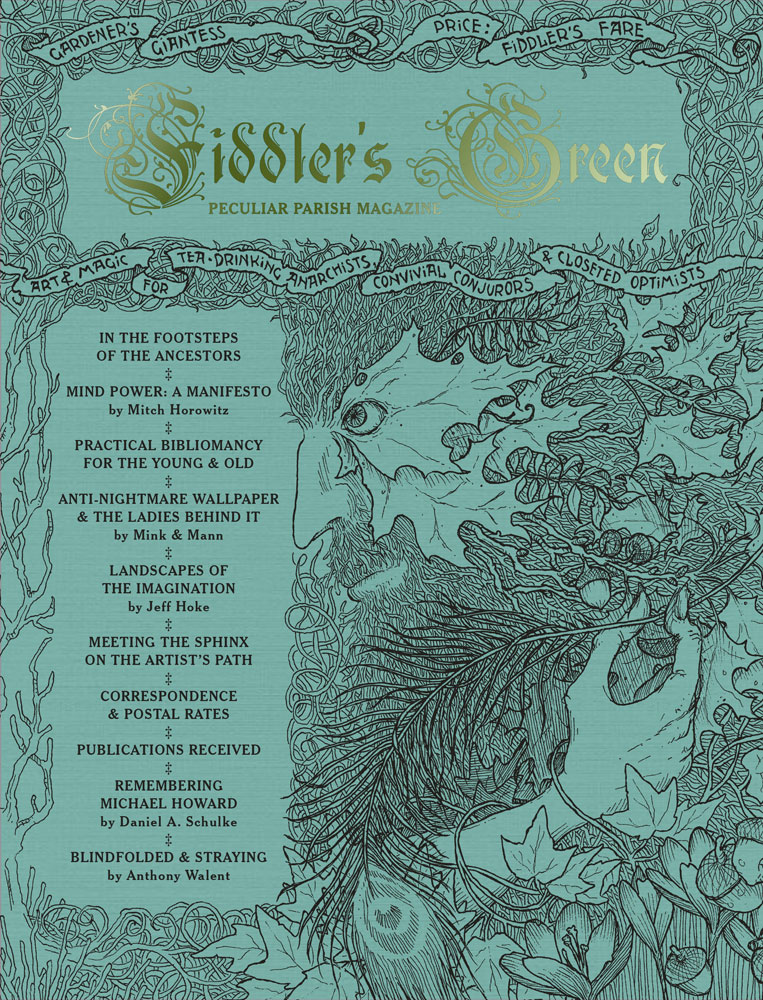

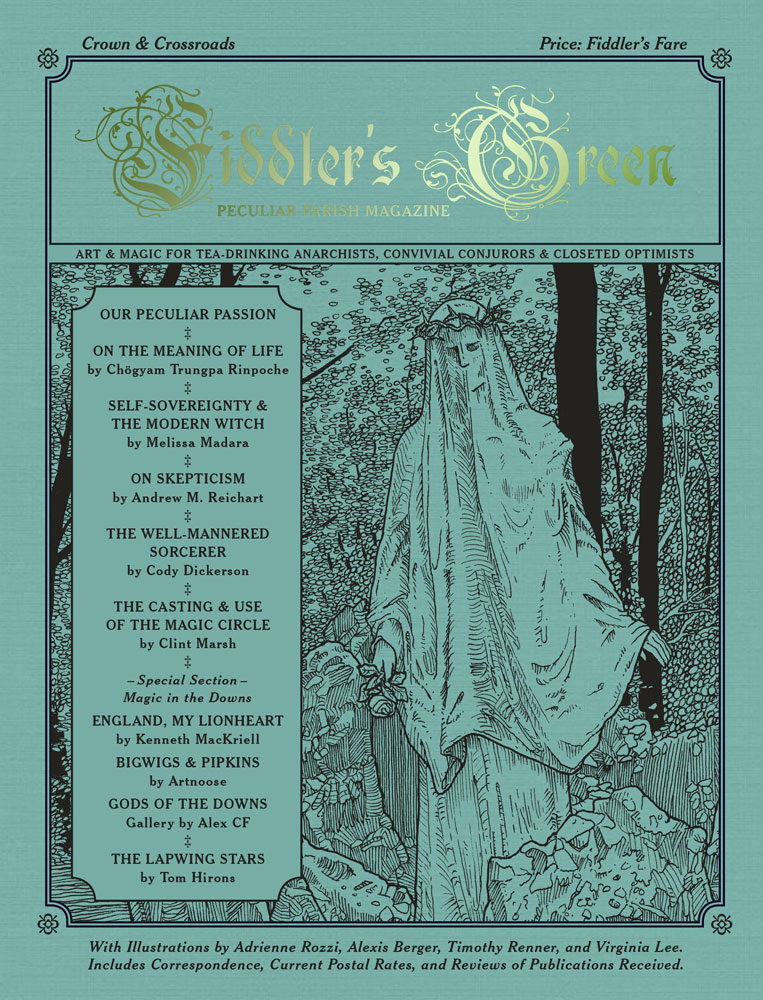

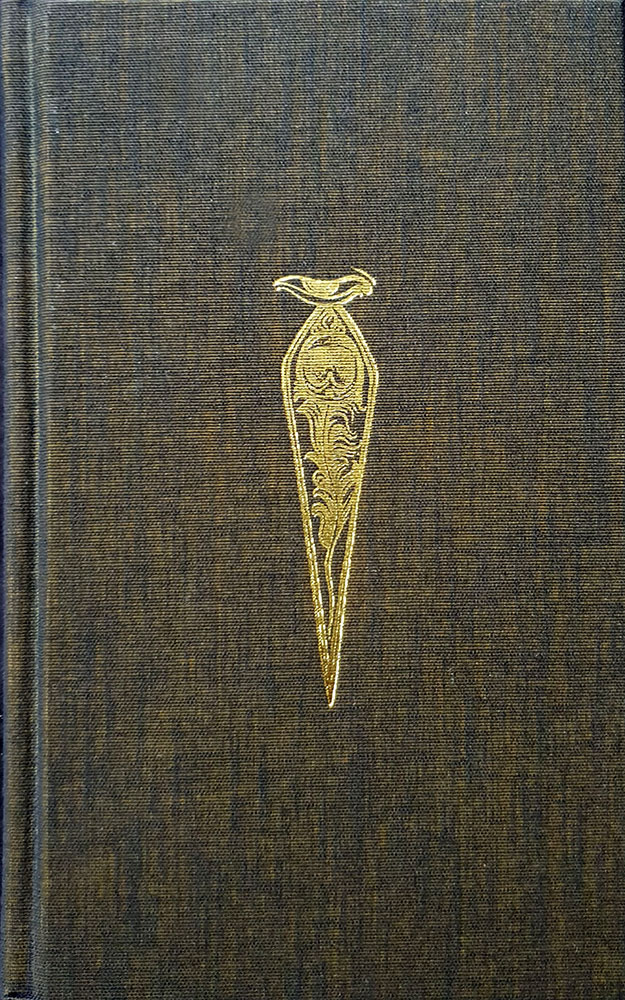

(h)Auroræ has an air of being McCaughry’s magnum opus, the sum result, from an aesthetic perspective, of all that he has done previously with his Anathema Publishing imprint. It’s gorgeously presented, intricately designed, with a poetic quality that is enigmatic and just a little bit impenetrable. At 304 pages and 5.25 x 8.5 inches dimensions, it feels substantial and weighty, the right size, texture and weight to convey a sense of significance and substance, fitting in your hands like a treasured tome, without being cumbersome. This aligns with statements McCaughry has made elsewhere, where he has talked of the magick inherent in books, and the profundity inherent in writing, producing and reading them.

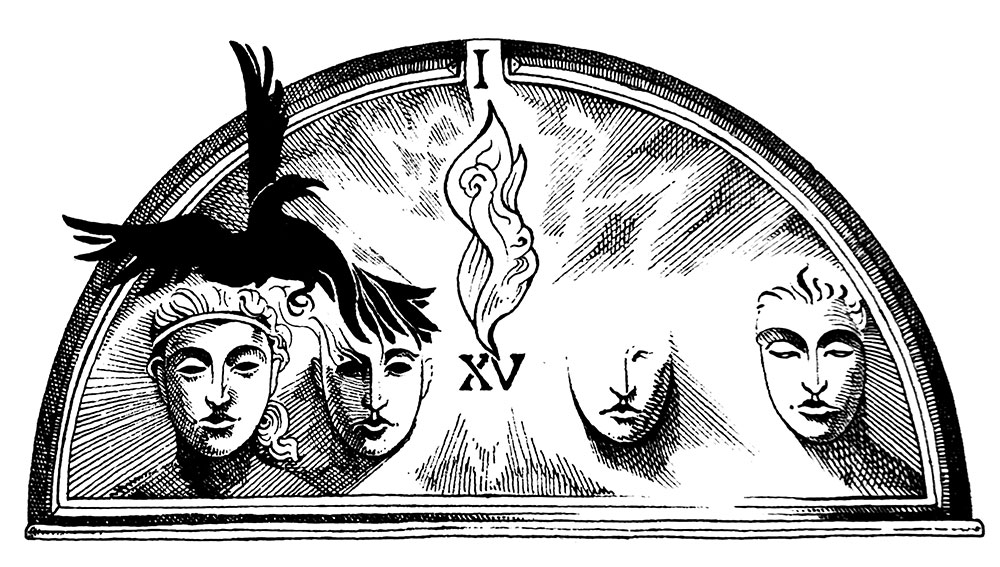

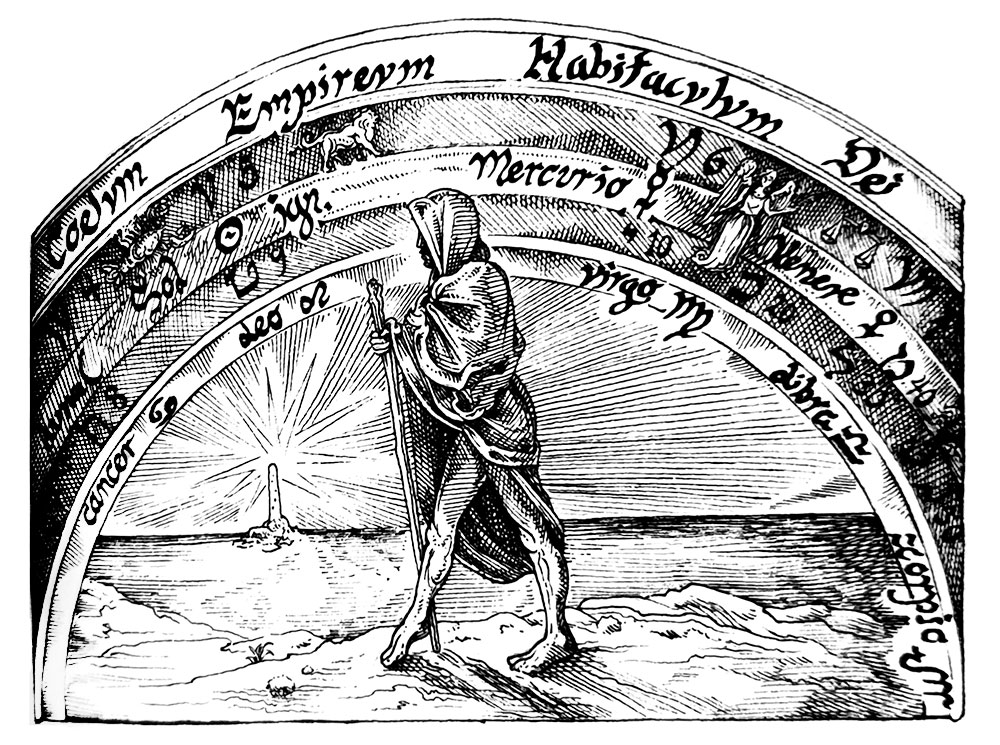

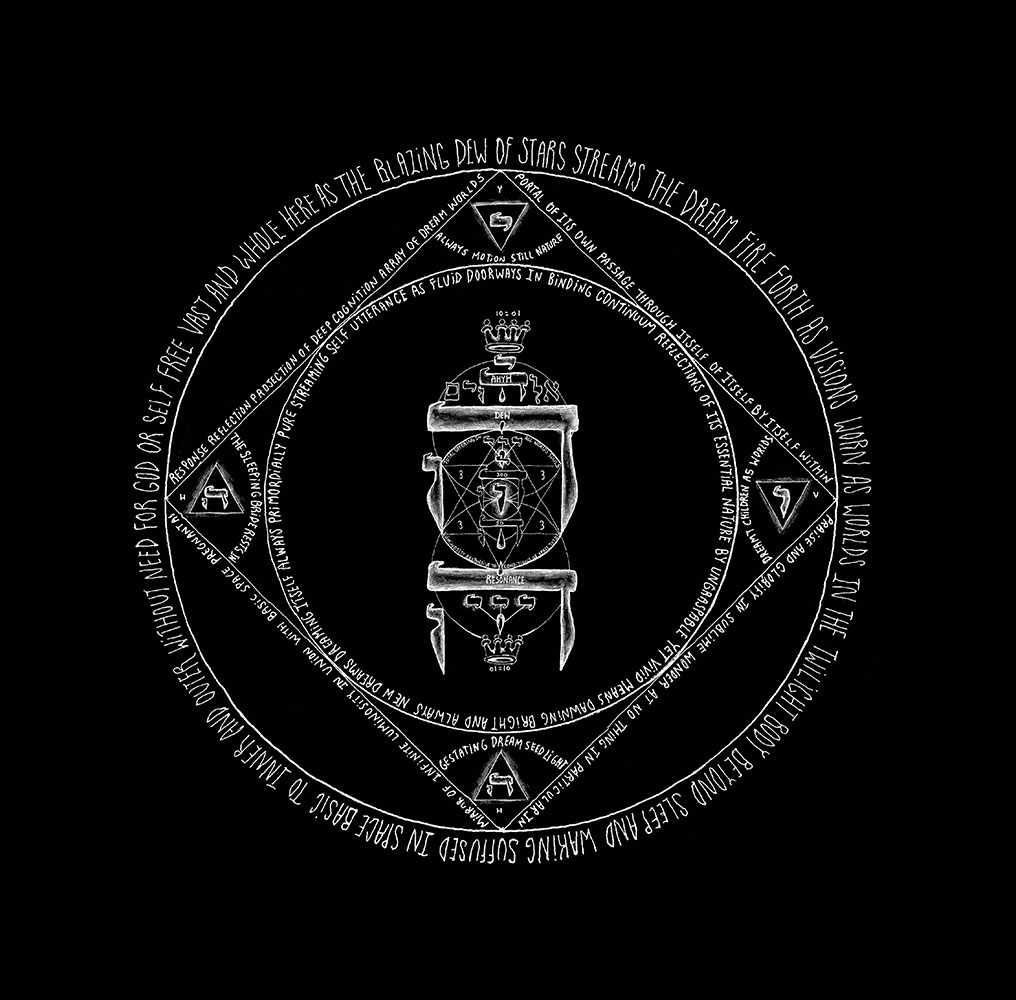

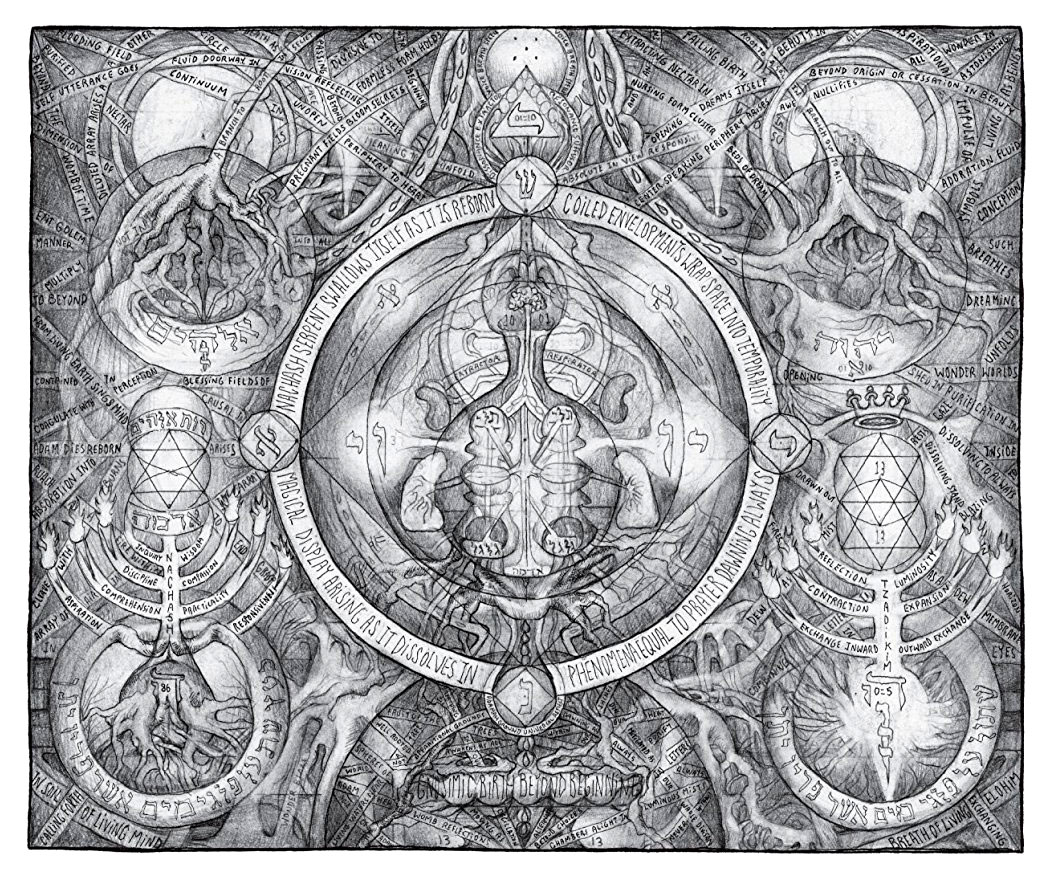

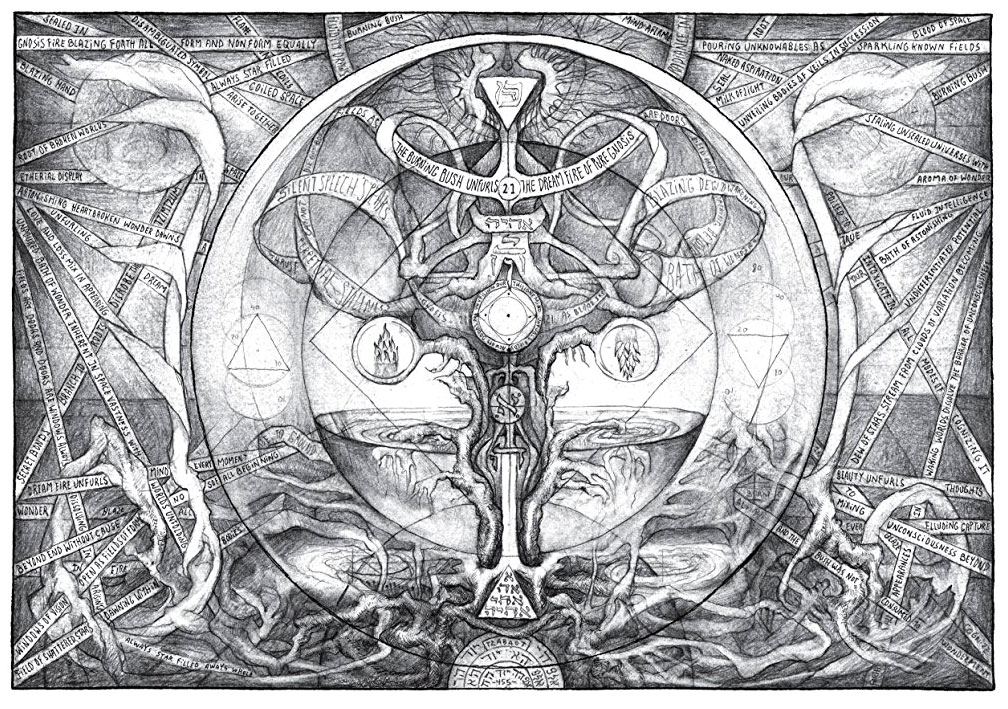

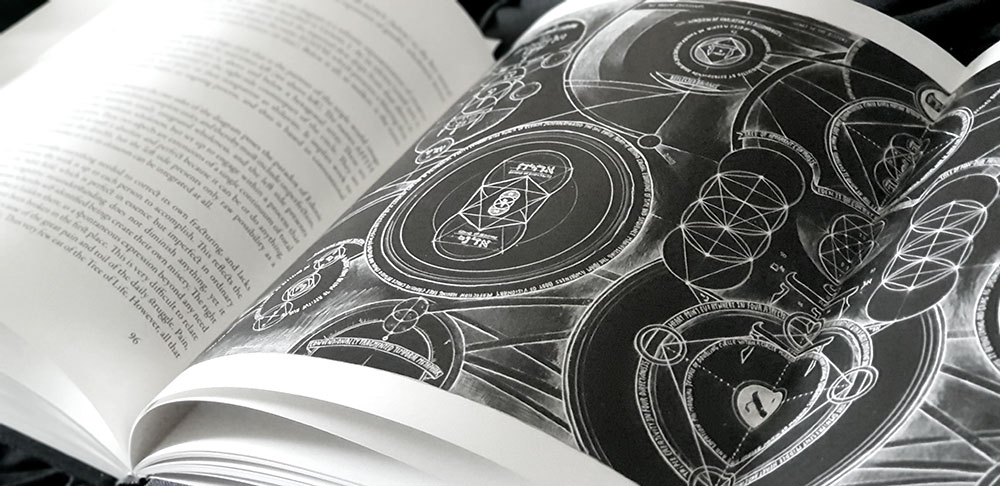

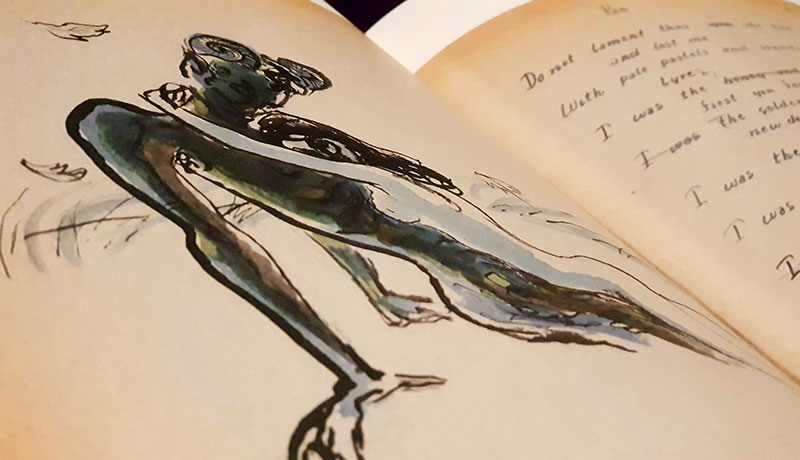

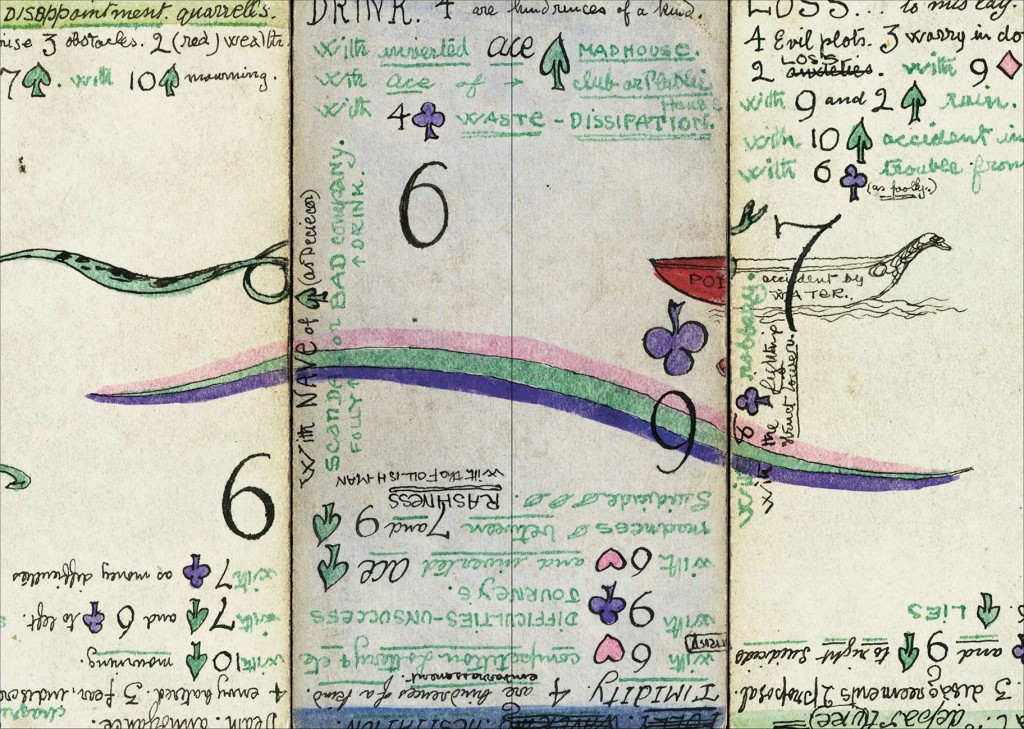

(h)Auroræ is divided into three main sections or books, the first of which reprises the (h)Auroræ title and is itself comprised of five codices; plus a long, circumlocutory introduction from Shani Oates. Each codex consists of short stanzas of poetry, formatted in a fairly large italic face and almost always accompanied with an illustration on the respective facing page. McCaughry’s style of verse is, one could charitably say, brisk, sometimes running to as little as four lines, with an economy of words that nevertheless draws from a clearly defined lexicon. He declaims, rather than rhymes, using archaic turns of phrase and employing a wide array of imagery that references a variety of mythological and magickal sources, including Luciferianism, tantra, alchemy, the Ruba’iyat and Mandaeism. This cornucopia of culture and its recherché language choices makes for a somewhat abstruse encounter, where you can get a sense of what is being said, but like alchemical texts of old, you’re never sure if you’re quite getting it all.

Book two of (h)Auroræ is titled Neoteric Heterodoxy and, for the most part, eschews the poetry format of its predecessor for a more discursive approach. Here, divided into three sections, McCaughry discusses various aspects of magickal theory and growth, with considerations of Gnosticism, doubt and truth, as well as the various forces, constructs and entities in his conception of a magickal cosmology: Lucifer, the Temple of LUh-hUR, the UmbraPlasma, the Monolith, the Quartz of Return, the Omni-Cipher, the Demiurge and the PCR or Prism Concrete Reality.

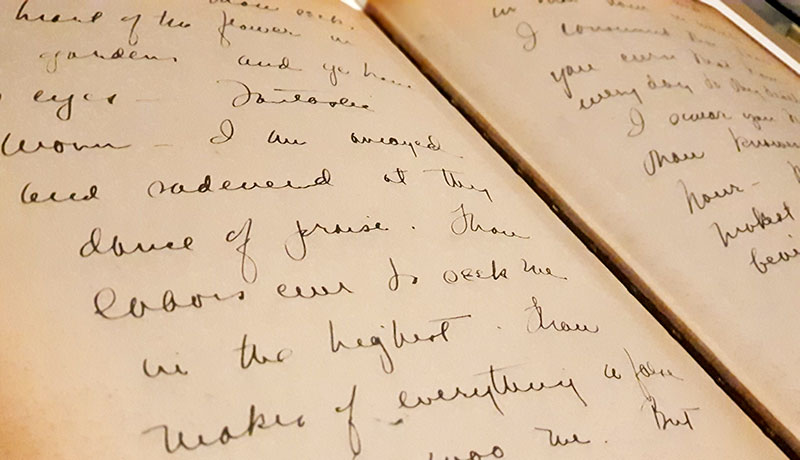

The third and final book of (h)Auroræ is called Anaphoras, Advent & Theurgia, and feels very much the conclusion, incorporating as it does various miscellanea and appendices. The lion’s share of this section takes the form of McCaughry’s account of the workings that form the basis of what is presented here, effectively his magickal diary fleshed out into a substantial narrative. He does not provide much in the way of explicit, point-by-point instructions, instead advocating for the ability of an adept to find their own tools and techniques; and emphasising the status of (h)Auroræ as a book of mysticism, rather than magick, with all the ritual rigmarole that the latter might entail. With that said, McCaughry’s magickal record is detailed enough that should one wish to emulate it, there is much to draw from.

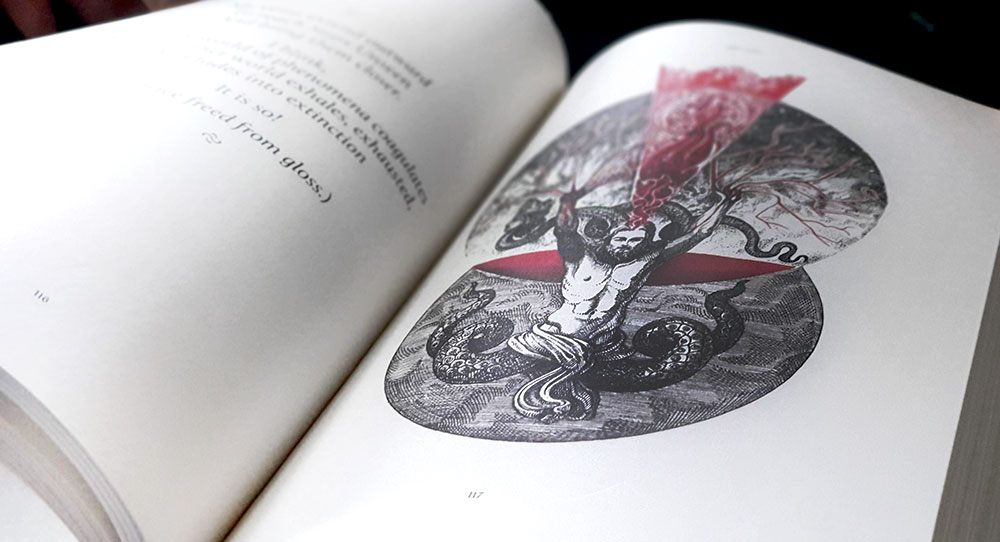

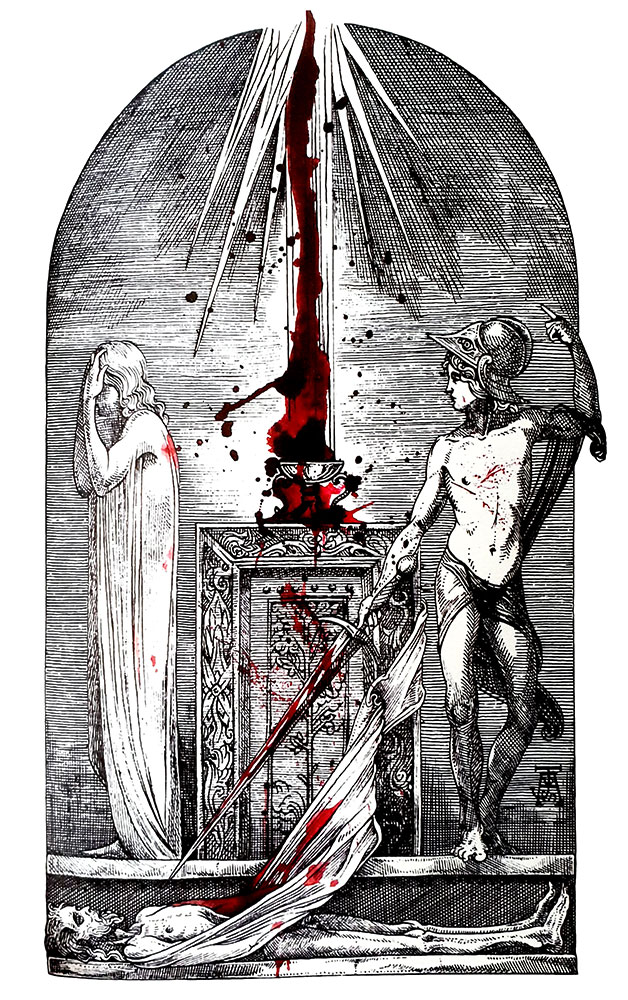

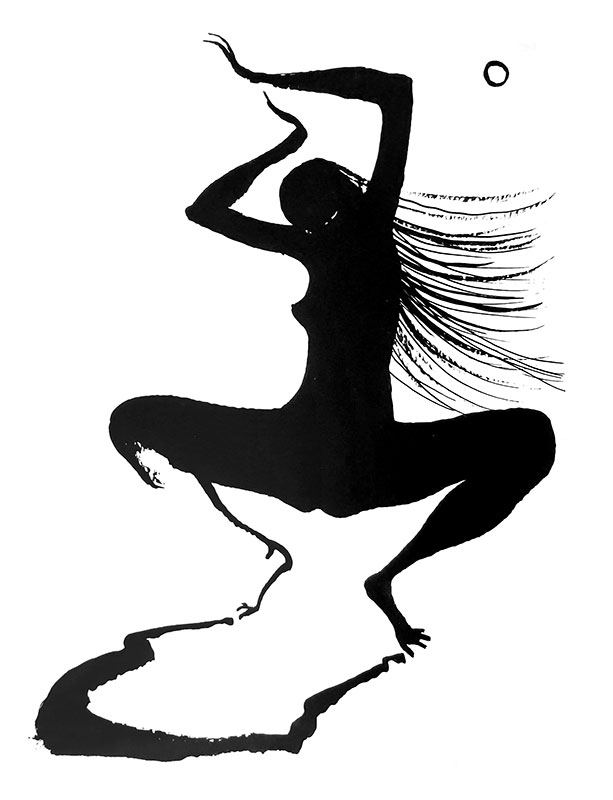

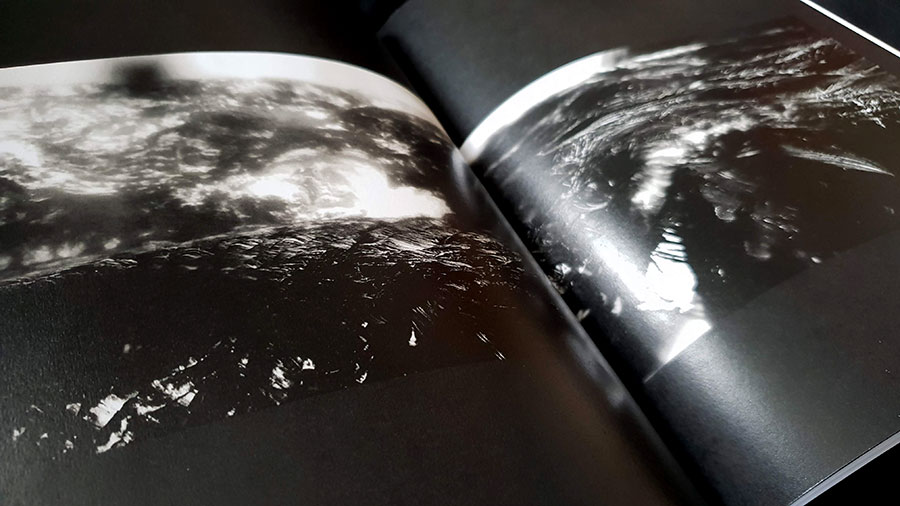

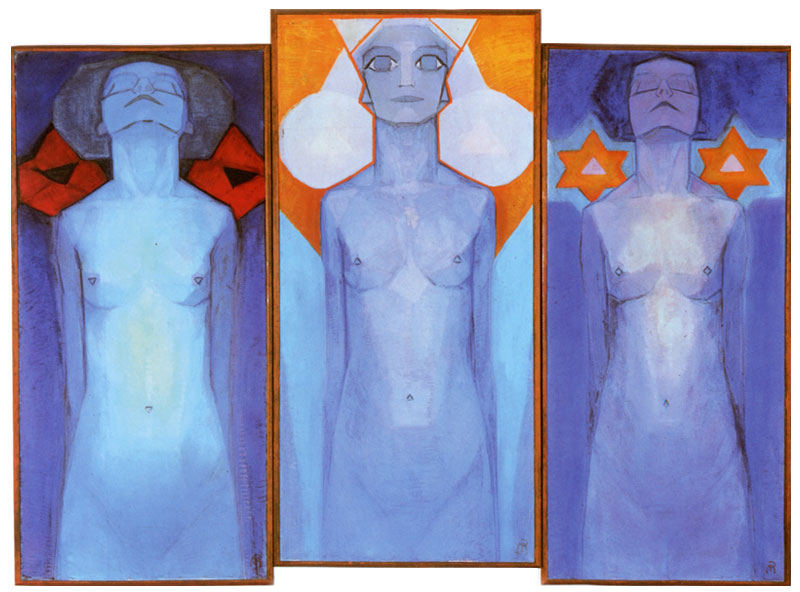

(h)Auroræ is profusely illustrated by José Gabriel Alegría Sabogal who almost deserves a co-author credit, such is both the impact and extent of his work. When almost every page within just the five codices of the (h)Auroræ section features an accompanying and presumably bespoke image, the amount of work is staggering; as is the cost, unless Sabogal severely undercharges for his work. There is an indefinable something about Sabogal’s illustrations, something that conveys an inherent sense of mystery and gnosis, but also somehow manages, with an apt turn of phrase, to keep silent.

Sabogal employs fine ink lines in a timeless manner that apes the look of traditional engraving, something that is reflected in the subject matter, where classical sculptures and equally sculptured bodies abound. In some instances, the lines of fine black ink are highlighted with striking washes of red, filling in spaces in some examples, and splattering across the image as blood in others.

Helpfully and fittingly, Sabogal speaks to his role in the book in The Birds That Speak At Dawn, his own chapter at the conclusion of (h)Auroræ. Here, he describes his and McCaughry’s shared creative journey, but also provides an explicit overview of the entire book, highlighting its passage of transmutation that begins with death and putrefaction and proceeds through four other alchemical stages symbolised by birds. Sabogal talks of dreams in which he discovers strange books filled with mysterious emblems, and thanks to his work here he may have created just such an oneiric tome.

In addition to Sabogal’s illustrations, (h)Auroræ succeeds in matters aesthetical with McCaughry’s typesetting and layout, which compliments the graphic content and showcases the written. For anyone that has seen McCaughry’s hand in the layout of other Anathema publications, there will be much here that’s recognisable, with the return of some familiar treatments and typeface choices. McCaughry has an antique typographic style, especially noticeable in the frontispieces that synthesise a variety of faces, styles and sizes, all perfectly balanced in their hierarchy and not cluttered or messy. With that said, there’s no slavish beholding to archaisms here, but rather a classic timelessness that joins rarefied presentation with readability.

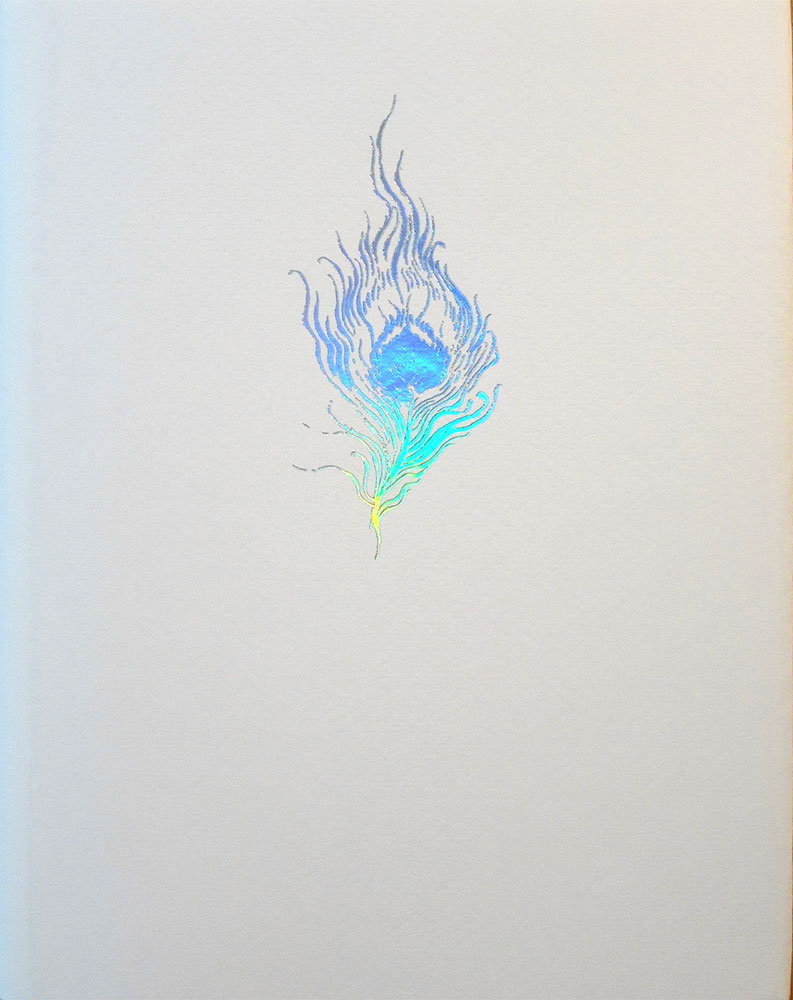

(h)Auroræ was made available in three editions: a standard edition of 500 individually hand-numbered copies, a collector’s edition of approximately 125 copies, and an eleven copy artisanal Spume of Luna edition. The standard hardcover edition of (h)Auroræ measures 5.25 x 8.5 inches, with 304 Cougar Natural 160M archive-quality paper pages bound in a lovely metal-flecked Italian Tele Legatoria Bronze bookbinding cloth. A design on the front is foiled in gold, as is the title and author on the spine. The collector’s edition is the same as the standard edition but bound in Eurobound Black Flanders (bonded leather), with gold foiling on the spine and a more complex design on the cover, incorporating blind-debossed elements. The eleven copy Spume of Luna edition, individually hand-numbered, signed and glyphed by the author, is three-quarter-bound in genuine Black Galuchat Ray rawhide, and white cow leather with gold foil blocking on the cover, and a blind-deboss on the back cover. The interior features handmade endpapers, in addition to those used within the standard hardcover edition.

Published by Anathema Publishing