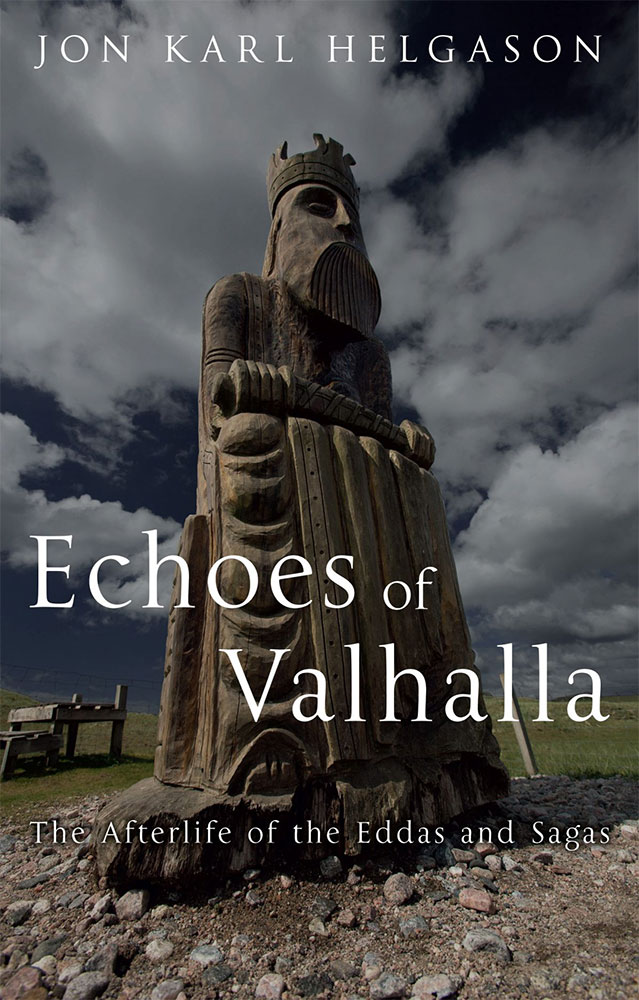

Carl Abrahamsson’s Source Magic marks his third appearance for Inner Tradition, having debuted in 2018 with Occulture, a work which considered the intersection of the occult with art and culture, and then releasing a biography of Anton LaVey in 2022. This new title follows in the footsteps of Occulture by being released by Park Street Press, a lesser known Inner Traditions imprint which focusses on psychology, consciousness studies, and psychedelics. And like Occulture, this is a work concerned with the way in which magic has infused human history and culture, being, as Abrahamsson terms it, a node around which all human activities revolve. This premise is very much in Abrahamsson’s wheelhouse, allowing him to do what he often does and focus on particular, often recherché, little pockets of occulture that can then be expertly and enthusiastically contextualised within a greater whole. The point of difference, as Nicholaj de Mattos Friswold notes in a foreword, is an experiential one, with Abrahamsson zeroing in on various places or moments he has been personally involved with; experiences that he describes as being “malleable nodes of wide-eyed amazement” whose reception creates a constant influx of magical stimuli.

Carl Abrahamsson’s Source Magic marks his third appearance for Inner Tradition, having debuted in 2018 with Occulture, a work which considered the intersection of the occult with art and culture, and then releasing a biography of Anton LaVey in 2022. This new title follows in the footsteps of Occulture by being released by Park Street Press, a lesser known Inner Traditions imprint which focusses on psychology, consciousness studies, and psychedelics. And like Occulture, this is a work concerned with the way in which magic has infused human history and culture, being, as Abrahamsson terms it, a node around which all human activities revolve. This premise is very much in Abrahamsson’s wheelhouse, allowing him to do what he often does and focus on particular, often recherché, little pockets of occulture that can then be expertly and enthusiastically contextualised within a greater whole. The point of difference, as Nicholaj de Mattos Friswold notes in a foreword, is an experiential one, with Abrahamsson zeroing in on various places or moments he has been personally involved with; experiences that he describes as being “malleable nodes of wide-eyed amazement” whose reception creates a constant influx of magical stimuli.

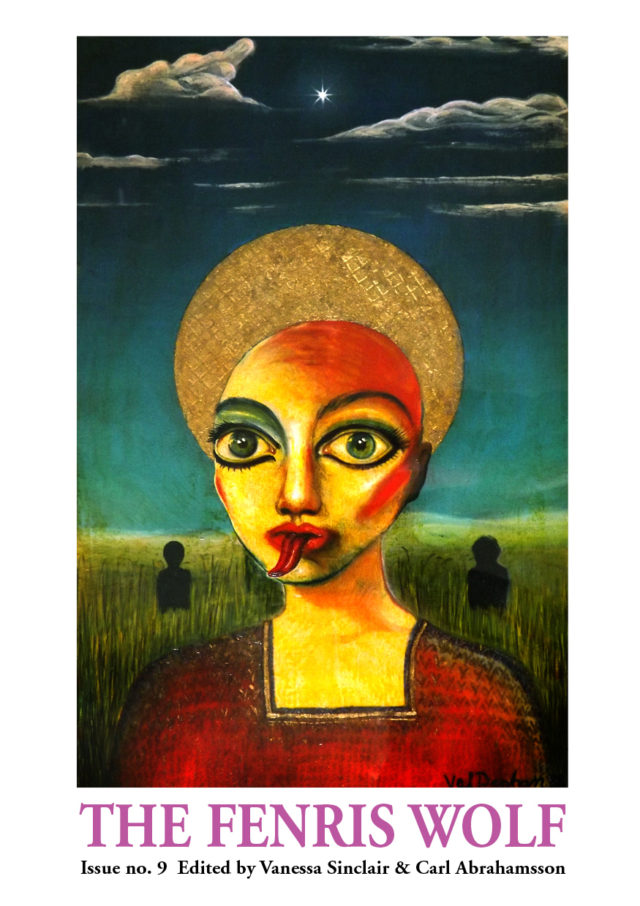

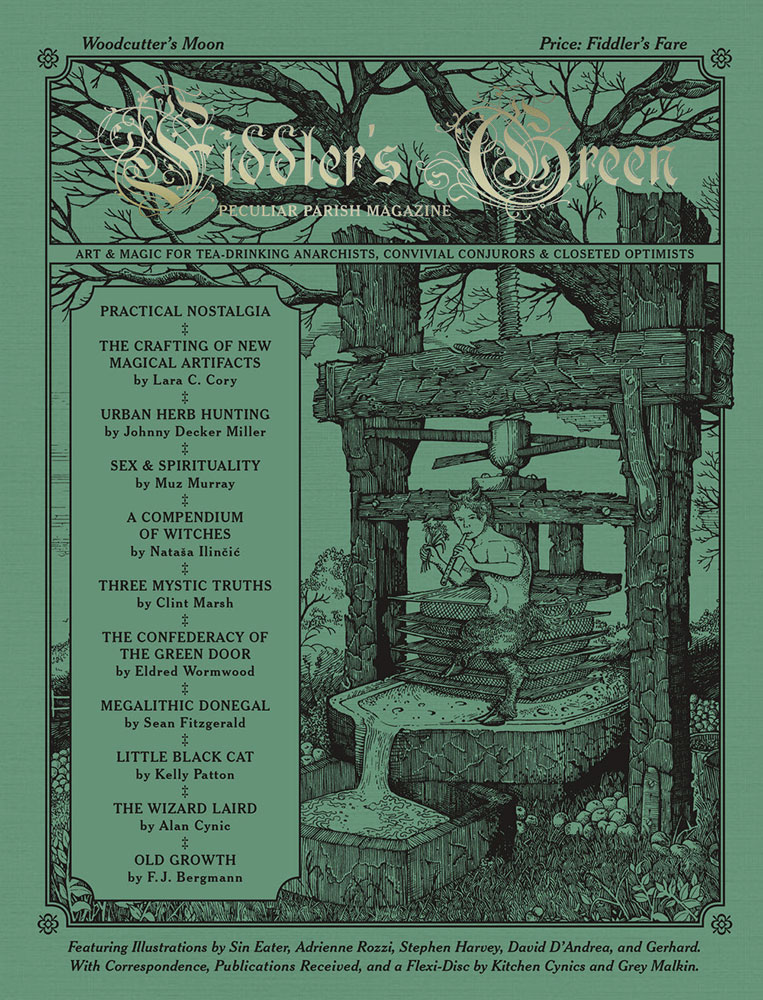

As part of this focus on the personal, Abrahamsson’s modus operandi is about discovering the magical and numinous within the everyday, of cultivating an accretion of significant experiences, be they editing, as he does, the journal The Fenris Wolf, a rather more exotic expedition to Tibet, or something seemingly more mundane, such as finding significance in a trashy Mondo film. As a result, Source Magic explores a variety of small yet vital fragments from within this holistic magical worldview, with each providing an opportunity for greater explorations of adjacent ideas. This fragmented nature also denotes the process behind this book, with many of the chapters having been previously published in magazines and journals, or presented as lectures.

It is journeys that fittingly begin this collection, setting off with two entries that use as their equally fitting narrative, that most magical type of journey, the pilgrimage. In the opening We’re On the Road to Somewhere, the pilgrimage is one effectively to Ernst Jünger, with Abrahamsson detailing a trip through Tyrol from Wien to Upper Swabia, arriving at the Jünger-Haus in Wilflingen, before ending the journey in Zurich. The second pilgrimage is to Morocco, focussing heavily on the Master Musicians of Joujouka, who provide an interesting nexus betwixt Abrahamsson and related occultural touchstone such as Brian Jones, Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, Brion Gysin and the Beats. The essay’s title Panic Pilgrimage underscores a particular interest in the caprine trickster figure of Bou Jeloud, who is credited with teaching the Master Musicians their music, and who was assumed by Gysin to be a local variant of goat-footed Pan. In both of these entries, Abrahamsson writes with an enthusiasm that lifts the narrative far beyond mere travelogue, never missing a moment to muse on some great magical truth, or to inject a little humour, such as when he self-deprecatingly describes himself doing a “slightly hesitant, Swedish old guy dance” to the swirling, transportive music in Joujouka. In the first pilgrimage he is able to wax about the beauty of the land, buildings and the Schwarzwald, and then equally turn that enthusiasm and delight to Jünger, writing ecstatically of being mesmerised by the experience within the Jünger-Haus.

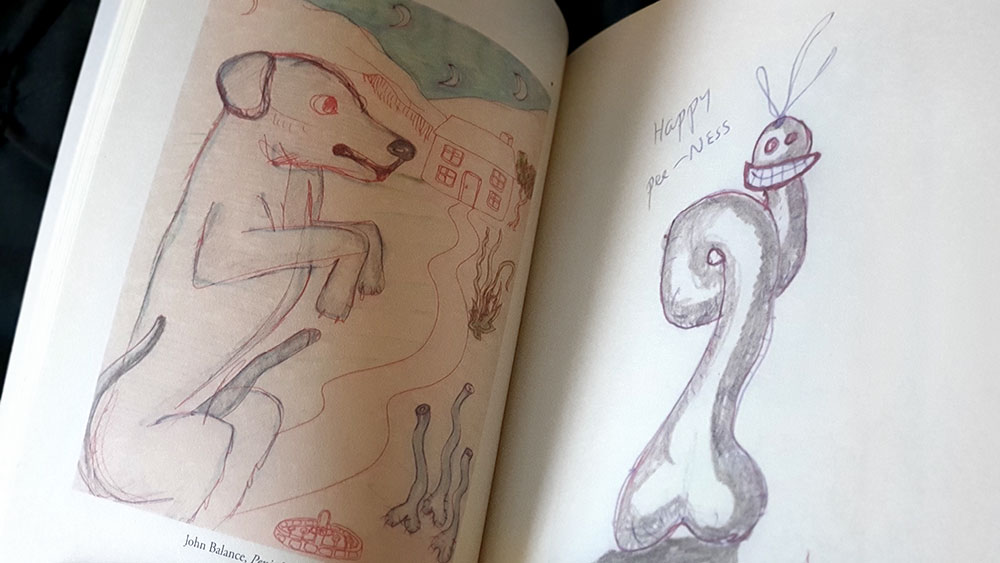

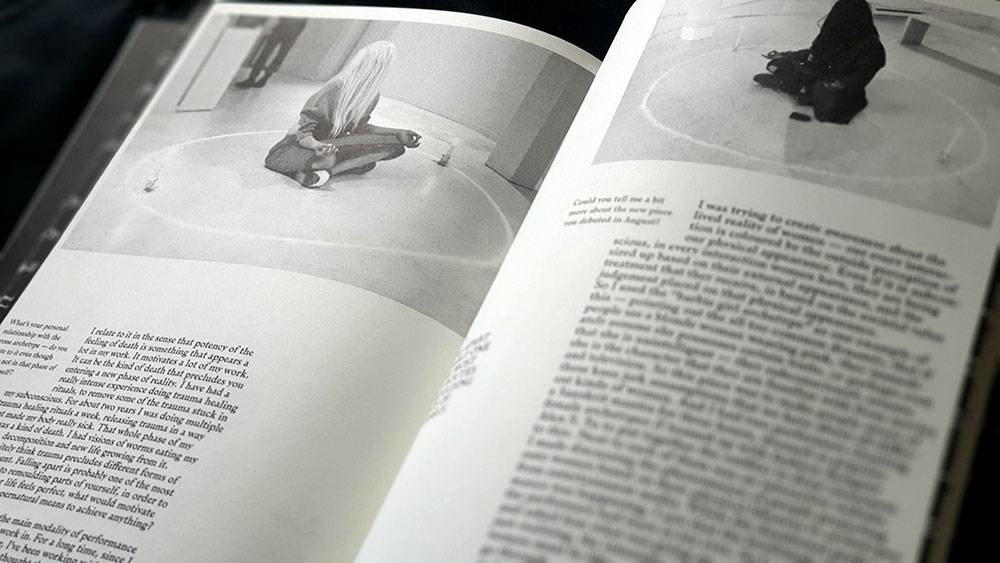

Like the twin pilgrimages that opened Source Magic, the next three entries are very much of a kind, sharing similarities and connections by being portraits of two significant occulture figures: Derek Jarman and his occasional collaborator Genesis Breyer P-Orridge. Gen receives two pieces, one originally written for The Brooklyn Rail arts journal, while the other is the introduction from Genesis P-Orridge: Temporarily Eternal: Photographs 1986-2018, a book of photos of he/r, taken and published by Abrahamsson. Both pieces bear witness to Abrahamsson’s three decade association with Gen, and given that both were written after he/r death, there’s something of a eulogistic, sometimes near hagiographic, tone. The first piece feels like a brief obituary at eight pages, appearing amongst a slew of other eulogies for Gen in The Brooklyn Rail a month following h/er death. It paints a personal picture of Gen and covers off major moments of h/er life, before ending with a prickly suggestion, judiciously not included in The Brooklyn Rail version, that anyone that might criticise or find fault with Gen is just a hanger-on who wouldn’t have had a career without them. The second entry tells a longer tale, documenting more fully Abrahamsson’s thirty year association with Gen, and commendably not feeling at all like a repeat of its shorter predecessor. Genesis then bleeds he/r way into the next chapter, Tripping the Dark Light Fantastic, a discussion of cinema that has as its foundation a meditation on Derek Jarman’s 1981 short film In the Shadow of the Sun, for which Throbbing Gristle provided the soundtrack.

The moving image once again features in a paean to the Mondo shockumentary films that Abrahamsson so adores, and then in a consideration of Patrick McGoohan’s classic television series The Prisoner. The latter doesn’t just lionise the series but places it within the context of its time, with the growth of psychedelic counterculture and its innate opposition to systems of control. Ambrahamsson ties this unruly spirit back to antecedents in New Thought movements, seeing The Prisoner as a Thelemic myth, or a Gurdjieffean wake-up-call.

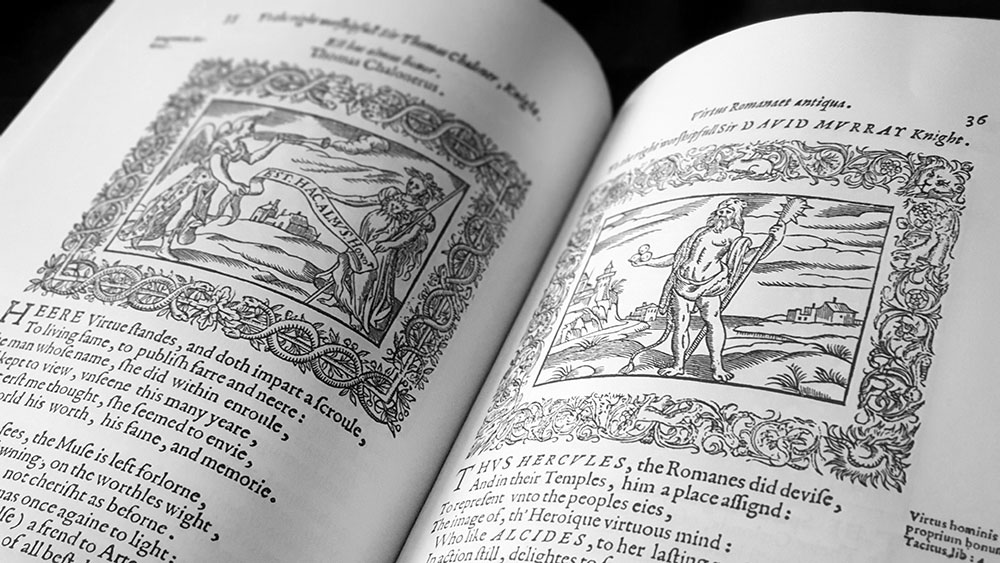

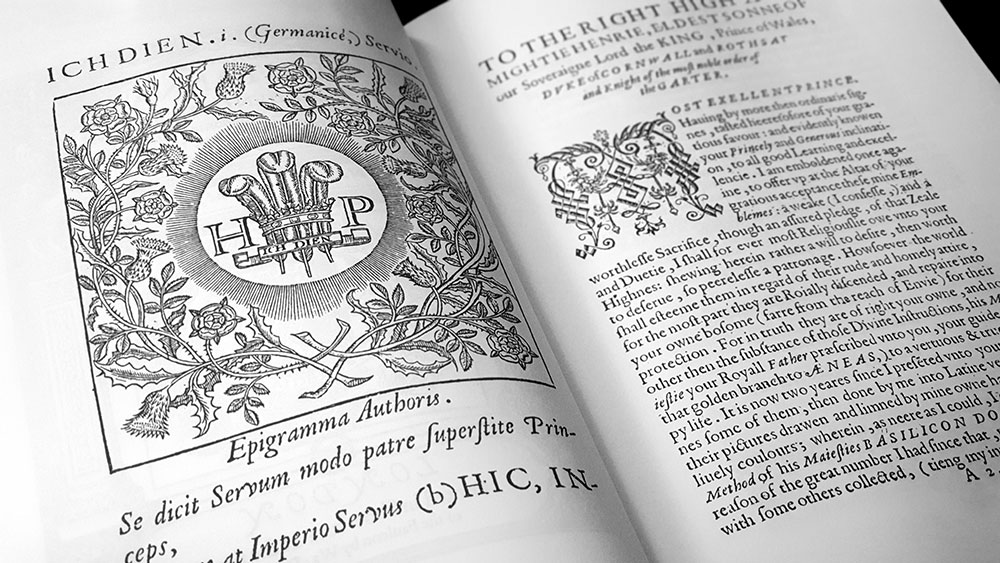

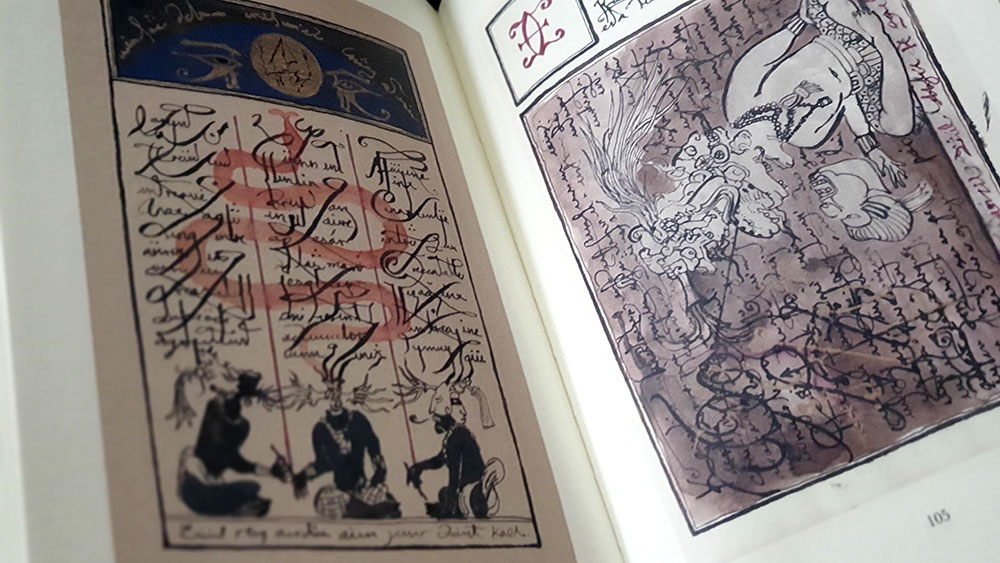

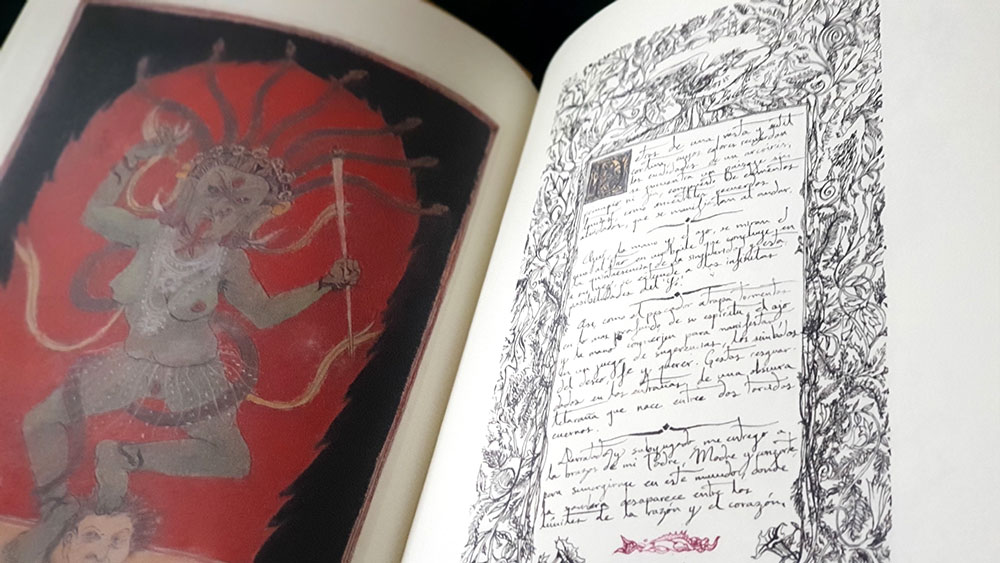

There is a carefully considered sensibility to how the entries in Source Magic have been curated and sequenced here, with the earlier grouping of pilgrimages and the nexus of Jarman/Genesis finding a latter mirror in various pieces on Ezra Pound and Austin Osman Spare. The first focuses entirely on Pound, largely through his relationship with his long-suffering publisher James Laughlin, who had founded the New Directions publishing house on Pound’s advice. In the second, Abrahamsson compares Pound and Spare, delivering on the punning promise of the title, Spare Me a Pound, and highlighting some of the similarities between both men. Of particular note is their mutual use of ideogrammatic methods to achieve clarity in communication: Pound in his incorporation of Chinese characters (most notably in The Cantos), and Spare in his use of sigils and the alphabet of desire.

Some of the entries that make up Source Magic feel less concerned with specific artists or works, and instead focus more on philosophical or metaphysical concepts, with the artist and genres simply providing the essay’s foundation, a leaping-off point. A discussion of magical realism, for example, nominally namechecks familiar authors of the genre, most notably Jorge Luis Borges, but quickly pivots to a consideration of magical realism in, well, reality. Here, Abrahamsson notes how the modern online-informed life of the 21st century is often suffused with what is fundamentally magic as meme, mirroring the type of memetic magic templated by the occult groups such as the Illuminates of Thanateros and TOPY. In another, an opening mention of Abrahamsson’s occult journal The Fenris Wolf provides a gateway to a general discussion of the actual Fenrir of Norse cosmology.

Source Magic concludes with a reprint of an interview with Abrahamsson, conducted by Iris and Matthew Samways for the Canadian record label Flesh Prison, who released his cassette album Reseduction in 2021. It is an interesting but hardly essential read, running to five pages like an unexpected appendix.

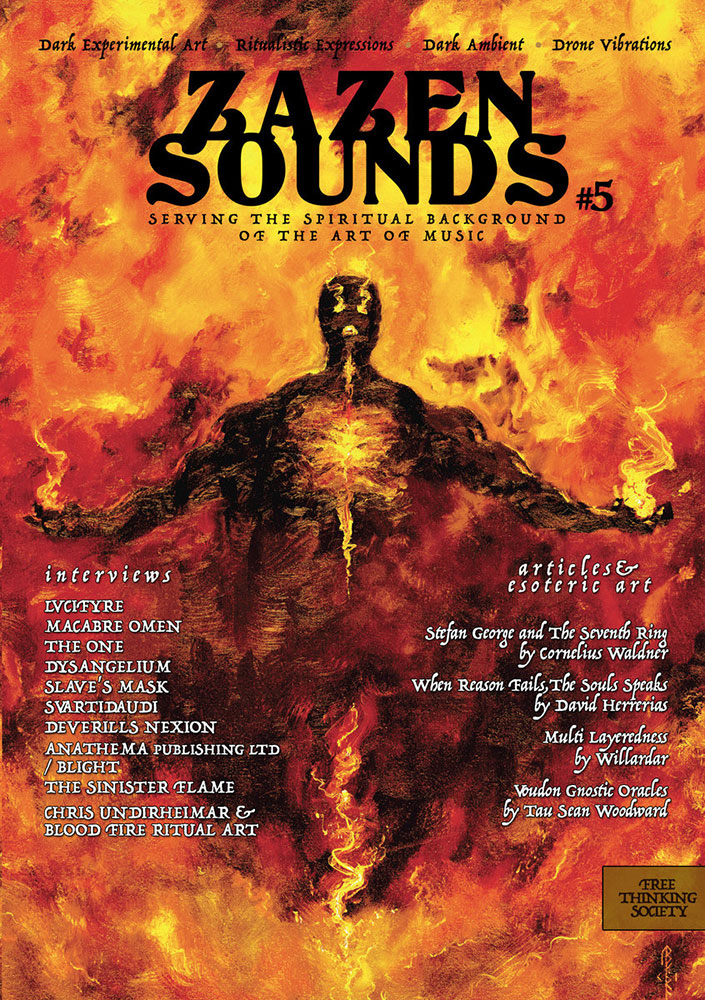

In all, this is an interesting collection of essays, with, arguably, something for everyone, though conversely, not everything will be for everyone, with, in the case of this reviewer, the more metaphysical and psychological speculation having less impact than those grounded in a particular artistic practice. Source Magic is presented in a fairly no-frills manner, with text design and layout by Kenleigh Manseau, who uses Garamond as a body face and the understated Nexa as the display for chapter titles (with the equally restrained Trajan Sans as chapter numbers). This austerity is continued in the graphical side of things, with the book containing zero illustrations, something of a surprise considering how many of Abrahamsson’s themes concern the visual arts.

Published by Park Street Press