It often seems that the field of occult publishing is a perpetual recycling station, producing a supererogatory glut of books that wander down far too well-trodden paths and offer little that is new. How many books have been written in recent years that give the same basic overviews of the runes, Western magic, or witchcraft, differing little from the ur-texts first published decades ago? It is a genuine joy, then, to come across Perttu Häkkinen and Vesa Iitti’s Lightbringers of the North, which in its 400 or so pages provides a thorough history of the occult traditions of Finland from the late 19th century to the present day. This is a veritable unexplored land from the limited perspective of Anglo-centric occultism, and seems even more unfamiliar than that of its Scandinavian neighbours.

It often seems that the field of occult publishing is a perpetual recycling station, producing a supererogatory glut of books that wander down far too well-trodden paths and offer little that is new. How many books have been written in recent years that give the same basic overviews of the runes, Western magic, or witchcraft, differing little from the ur-texts first published decades ago? It is a genuine joy, then, to come across Perttu Häkkinen and Vesa Iitti’s Lightbringers of the North, which in its 400 or so pages provides a thorough history of the occult traditions of Finland from the late 19th century to the present day. This is a veritable unexplored land from the limited perspective of Anglo-centric occultism, and seems even more unfamiliar than that of its Scandinavian neighbours.

Originally released in Finnish in 2015 as Valonkantajat: Välähdyksiä Suomalaisesta Salatieteestä, this 2022 edition from Inner Traditions is its first appearance in English. Perttu Häkkinen and Vesa Iitti have backgrounds in academia, with respective master’s degrees in philosophy and comparative religion, as well as, fun fact, a past in music, with the now-deceased Häkkinen having been one-half of the electro duo Imatran Voima, whilst Iitti is a former member of the grindcore band Repulse and its later incarnation, Xysma. The more you know.

As something of a serious study, things start a little dryly with perhaps the least glamourous of occult streams, Theosophy, in connection with the father of esotericism in Finland, Pekka Ervast, a founding member of the Theosophical Library of Helsinki, serving as the General Secretary of the Finnish Theosophical Society from 1907–1917 and 1918–1919, before creating his own Rosicrucian order, the Ruusu-Risti, in 1920. The second chapter follows a similar path, and the familiar esoteric figure in this instance is Georgij Gurdjieff who had an outré influence on Finnish esotericism, inspiring individuals and groups since at least the late 1960s. Karatas-kirjat began the publication of translations of works by him and his pupils in 1969, and the similarly-named Karatas society formed in 1979 to disseminate his and J.G. Bennett’s ideas.

It’s not all hoary old-head occultism here, and Häkkinen and Iitti do not shy away from the more lurid and scandalous side of sortilege. The first of these, The Hand in the Spring: The Mystery of Tattarisuo, documents the grisly incident from the 1930s in which human remains were found deposited in a spring in the rural outskirts of Helsinki. The remains had been collected by a small black magic group from graves in the Malmi Cemetery and used in ceremonies intended to contact spirits.

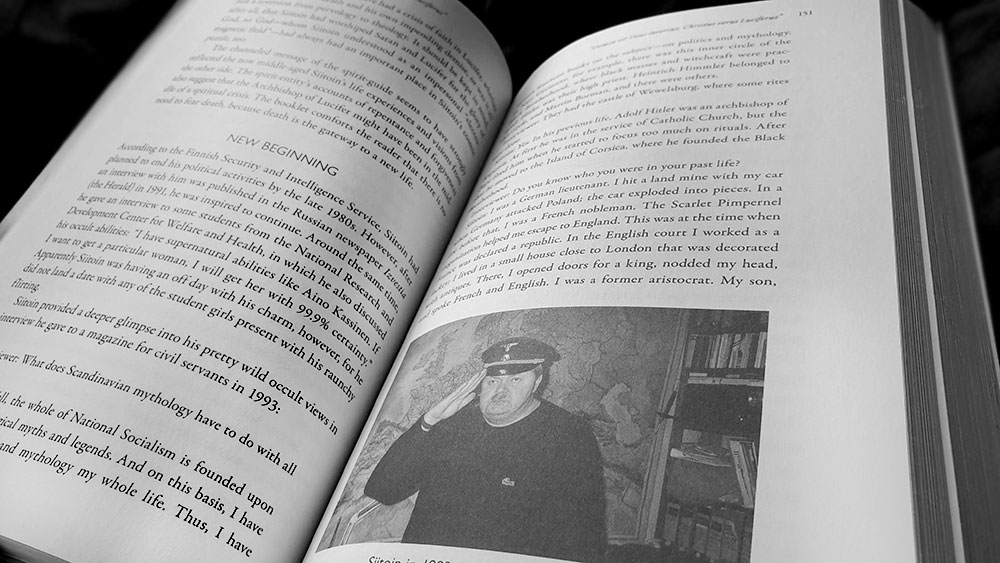

Speaking of scandalous, the book’s longest entry is dedicated to the neo-Nazi and Satanist Pekka Siitoin, grandly referred to here as the Archbishop of Lucifer. Like the Tattarisuo case, this represents a grottier side to occultism, with Siitoin appearing as an unappealing and unsympathetic 1970s edgelord whose base embrace of transgressive politics and esotericism was seemingly in lieu of having any intellect or class. This distain is engendered and exacerbated by the interminable 63 pages that are spent on him, exhaustively documenting someone who simply sounds intolerable. Plus, with his portly figure and rotund face, he looks eerily like Benny Hill, and when he is seen raising his arm to give the Hitlergruß he seems to embody Hill’s character Fred Scuttle giving an adorable forehead-pressing salute, rather than some Führer of Finland or Archbishop of Lucifer.

Siitoin’s association with nationalism allows Häkkinen and Iitti to take a slight diversion from these chronologically-ordered individual case studies and dedicate a chapter to the broader connections between Occultism and Finnish Nationalism. This showcases a range of figures, each a little bit nutty, including the artist, pseudo-linguist and, erm, ‘Fenno-Egyptologist’ Sigurd Wettenhovi-Aspa (who believed that Finnish was the world’s proto-language and that Finns came from Ancient Egypt). Then there’s the writer Esko Jalkanen (who gave the Finns an Atlantean origin), anthropologist and Ahnenerbe-member Yrjö von Grönhagen (who, we learn, once washed Karl Maria Willigut’s back with a magical stone from Karelian seer Pekko Shemeika), and Siitoin associate Väinö Kuisma (who blended Finnish mythology with Esoteric Nazism and Evolian magical fascism, and notoriously features in the 1994 documentary Sieg Heil Suomi).

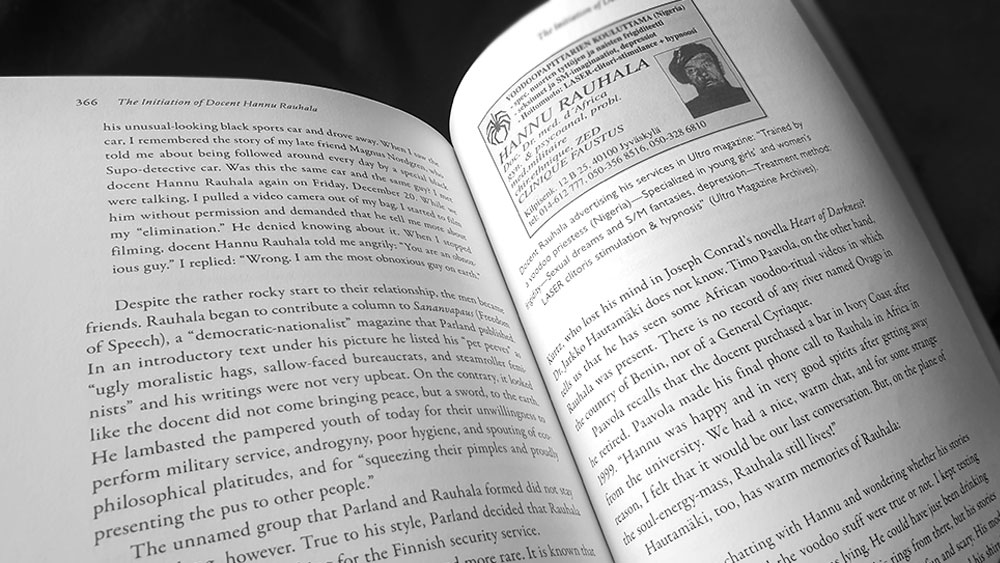

Strange and singular individuals are very much a currency throughout Lightbringers of the North, with chapter after chapter dedicated to odd men with equally odd ideas, each given an endearing or enigmatic sobriquet by the authors. There’s Jorma Elovaara, referred to as the Wellington Boot Prophet, who was the publisher of Tähti magazine and a significant counter cultural figure intersecting experimental music and art with Ufology, gay rights and esotericism. Then there’s Kauko Nieminen, the Santa Claus of Kulosaari, a self-taught physicist with all the scientific credibility engendered by that job tile, whose grand theories about ether vortices recalls speculative science several centuries older than him (and yes, he self-published his poorly reproduced works and sold them on the street, as is tradition). Not beating the weirdo allegations, we can’t forget Docent Hannu Rauhala, who claimed to have been initiated into voodoo in Nigeria and who offered his services in curing young women of their frigidity; and who in photos looks like a mercenary or Eugène Terre’Blanche.

One of the most interesting of these biographical subjects is Ior Bock, whom Häkkinen and Iitti delightfully refer to as the Sperm Magician of Gumbostrand, and the only participant in this parade of odd fellows that this reviewer was previously aware of. Rivalling Bock’s magnificent title as the Sperm Magician of Gumbostrand is the Sex Magick Soldier of Turku, known variously as dhLin gHa-Rej or Aswa Haidar el-Hayyat, or simply Reima Saarinen to his mum and dad.

As the narrative moves into more recent times, author, musician and former Setian Tapio Kotkavuori gets pretty much a whole chapter to himself. As the most prominent Finnish member of the Temple of Set, this makes sense, and Häkkinen and Iitti provide a brisk biography, charting Kotkavuori’s early formation of the Kalevala Pylon, his rise through the Setian ranks, followed by a temporary relocation to the United States and the eventual departure from the temple. It concludes with his death, or at least the death of the name Tapio Kotkavuori (suitably eulogised in a newspaper obituary in order to make it official) as the occultist formerly known as Tapio went on to new things. Other than Kotkavuori, Häkkinen and Iitti’s take on modern Finnish esotericism is pretty brief, with far too short sections on the Star of Azazel and other smaller Satanic groups, and no mention of a publisher like Ixaxaar.

The definition of occult within Lightbringers of the North is fairly broad and it is not, regrettably, all sperm magicians and sex magic soldiers, with Häkkinen and Iitti covering more Fortean paranormal pursuits as well, such as ufology, parapsychology, hypnosis and the psychic Aino Kassinen. One’s mileage may vary with regard to the appeal of such topics, but for this reviewer, they elicit a weary ‘pass.’ Throughout the book there is a palpable mix of writing styles, perhaps reflecting entries written solely by either Häkkinen or Iitti. The chapter The Clairvoyant of the Nation, with its biography of the aforementioned psychic Aino Kassinen, feels markedly different in tone to what precedes it, with a hint of a naïve school report or a first attempt at a marketing profile piece.

In all, this makes for a valuable work, providing important insight into magic beyond the Anglo-centric myopia of the United Kingdom and the United States. Lightbringers of the North has been formatted with layout by Virginia Scott Bowman and text design from by Debbie Glogover, using Garamond for the body face with Espiritu and Gill Sans as display faces.

Published by Inner Traditions