Bearing the subtitle The Power of the Cadaver in Germanic and Icelandic Sorcery, Cody Dickerson’s The Language of the Corpse is a short little treatise from Three Hands Press. Running to just 76 pages, undivided by chapters and with type set at a fairly large point size, it is an enjoyable one-sitting read that feels more like an extended essay or brisk thesis than a full book. This puts it in the company of another recent title from Three Hands Press, Richard Gavin’s The Moribund Portal, with which it shares a certain focus on matters of quietus.

Bearing the subtitle The Power of the Cadaver in Germanic and Icelandic Sorcery, Cody Dickerson’s The Language of the Corpse is a short little treatise from Three Hands Press. Running to just 76 pages, undivided by chapters and with type set at a fairly large point size, it is an enjoyable one-sitting read that feels more like an extended essay or brisk thesis than a full book. This puts it in the company of another recent title from Three Hands Press, Richard Gavin’s The Moribund Portal, with which it shares a certain focus on matters of quietus.

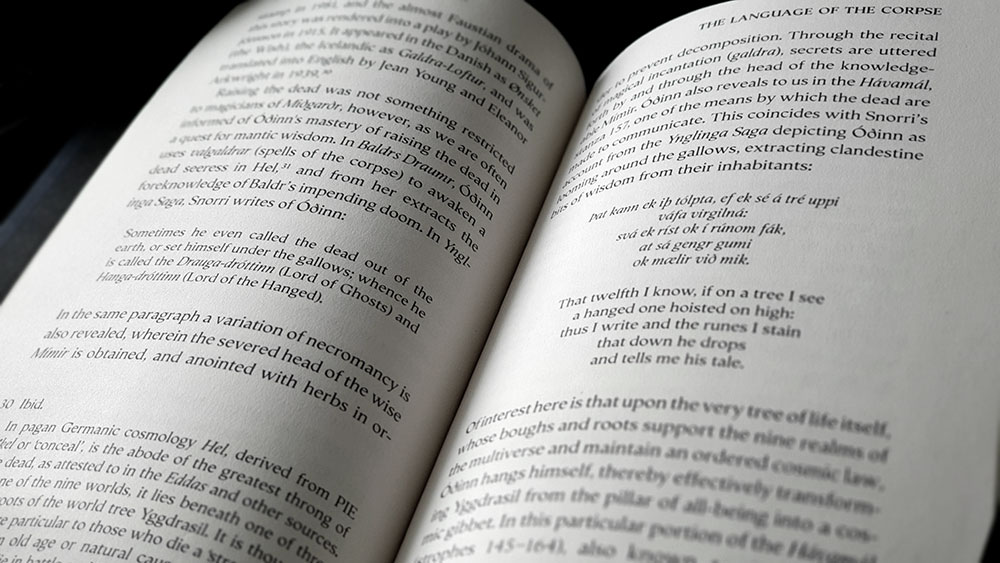

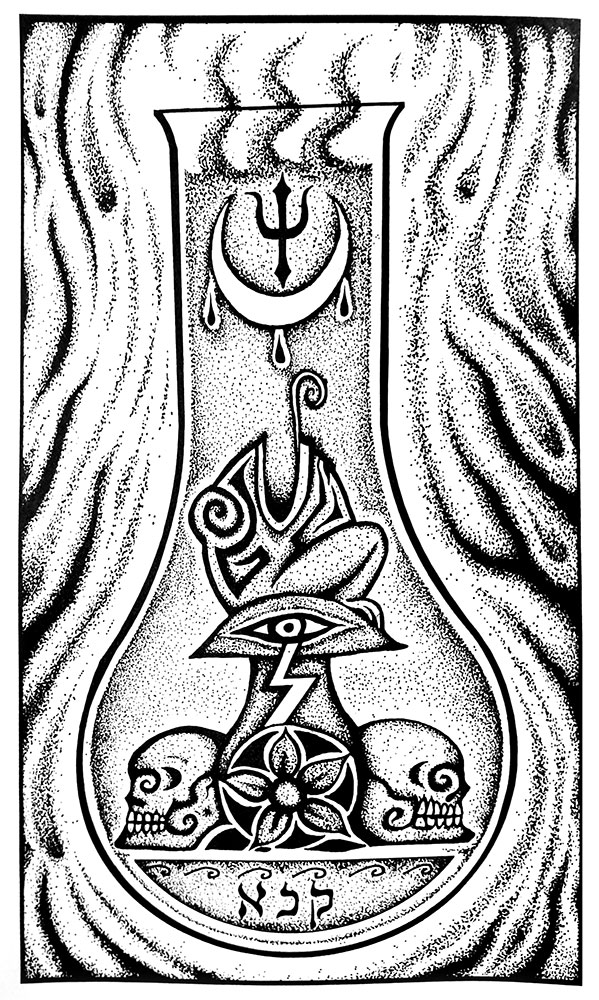

As the title and subtitle make obvious, the subject in hand here is a corporeal one, concerning itself with both symbolic and actual use of human remains for metaphysical purposes. Dickerson frames this consideration with Óðinn, who as Valföðr and Hangadróttinn, makes a fitting embodiment of the themes of death and vital remains that follows. While he doesn’t feature prominently throughout the rest of the book, it’s clear with this introduction, and his return at the conclusion, that from Dickerson’s perspective, he oversees it all.

The book’s remit allow Dickerson to amble through a variety of related objects, predominantly associated with Western Europe and more specifically with Scandinavia, where reanimated corpses loom large as symbols of eldritch alterity. Indeed, if there’s one theme here it’s how the remains of the dead, be it an entire body or the singular hand of glory, provided a method of congress between this world and others. For example, those Iron Age people whose bodies have been found in peat bogs may have been victims not of just sacrifice (in itself a form of connecting with the divine) but of augury, with their intestines read for import and wisdom. As Dickerson eloquently puts it, the corpse then acts as an agent by which the living gain access to the wisdom of the gods, becoming “a symbol of the highest degree of exchange between man and the divine,” and thereby the greatest possible offering.

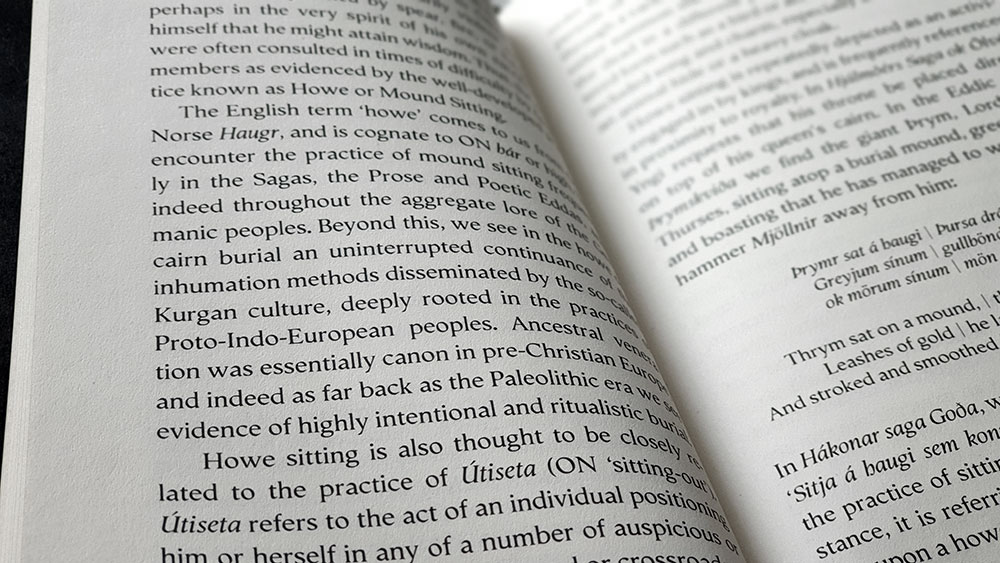

It is this sense of communication, of touching the divine, which can then be seen in the other examples that Dickerson draws on from across a substantial span of time and distance. Whether it’s figures sitting on burial mounds in saga literature, the necromancy of sixteenth and seventeenth century Icelandic sorcerers, or the belief in the apotropaic and sanative power of an executioner’s touch, there is a sense of death acting as a transmitter of power and knowledge, and for good as much as for ill.

There’s a certain familiarity that occurs in The Language of the Corpse, with little areas being covered that anyone immersed in this here milieu will, or should, have at least a passing awareness of due to their ubiquity. The intersection of mandrakes with this topology is the most obvious one, hitting all the usual talking points when discussing their connection with death and the gallows. Similarly, a brief foray into the idea of mumia, a protoplasmic cure-all made from human remains, echoes a similar survey of the subject from Daniel Schulke’s recently reviewed Veneficium.

Dickerson writes in a style that fits rather well with Three Hands Press. While not as ornate or antique as some of his companions, he nevertheless deftly employs a well-furnished lexicon and is able to dip into a conversational, but not too informal, turn of phrase when required to address the layreader. This is all, in turn, competently and thoroughly proofed, with no significant complaints from your humble reviewer.

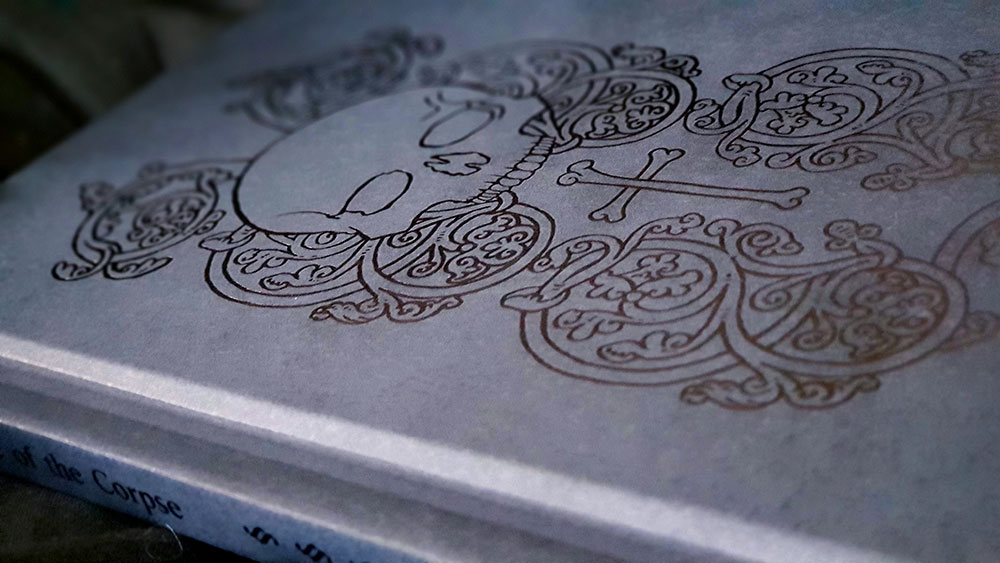

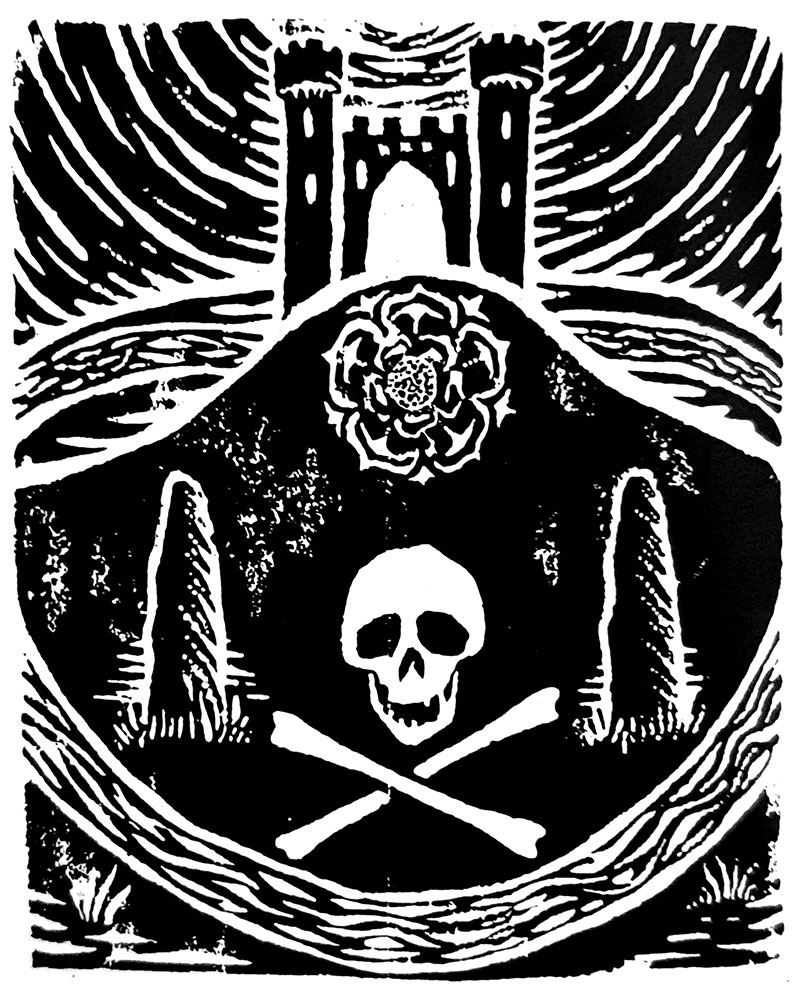

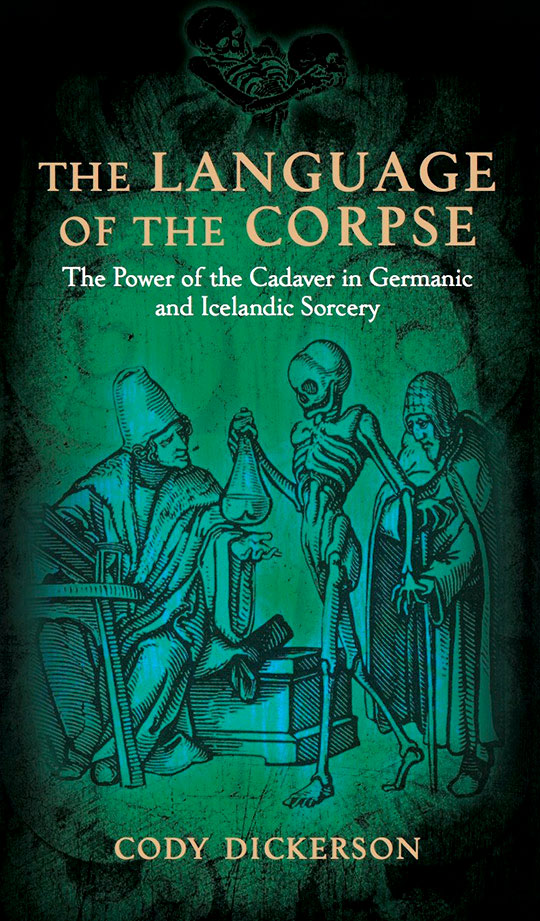

The Language of the Corpse has been made available in three editions: a trade paperback, a hardcover edition of 1,000 copies with a dust jacket, and a deluxe edition with special endpapers and quarter leather binding. The dust jacket and paperback version features a collage designed by Bob Eames, based on The Physician from Hans Holbein’s The Dance of Death, while the front and back of the hardcover edition is debossed with a lovely floral skull motif, cruelly hidden by said dust jacket.

Published by Three Hands Press