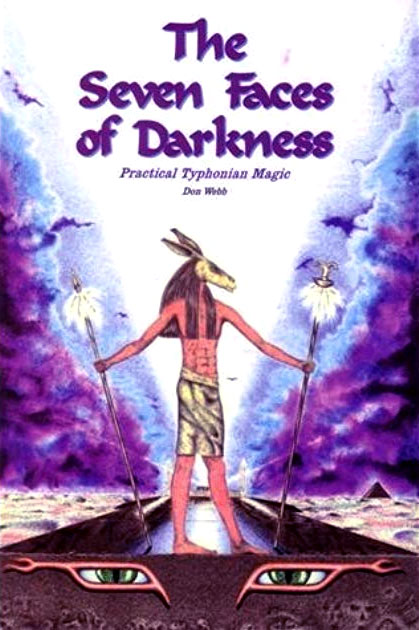

As a sequel to the December review of Set by Judith Page and Don Webb, we get nostalgic with a look back at the first book from Webb to make it into the nascent Scriptus Recensera library. Published in 1996, the year that Webb would become High Priest of the Temple of Set, The Seven Faces of Darkness identifies itself on the title page as the first volume of the proceedings of the Order of Setne Khamuast, a Temple of Set order that Webb was then the grandmaster of. There doesn’t seem to have been any subsequent volumes to these proceedings, but what is presented here speaks to the order’s raison d’être of combining scholarship with magical practice. The blurb on the back of the book suggests a similar motivation, mentioning Webb’s hope that it will be “a partial antidote to the fuzzy thinking of the occult world,” – wonder how that turned out.

As a sequel to the December review of Set by Judith Page and Don Webb, we get nostalgic with a look back at the first book from Webb to make it into the nascent Scriptus Recensera library. Published in 1996, the year that Webb would become High Priest of the Temple of Set, The Seven Faces of Darkness identifies itself on the title page as the first volume of the proceedings of the Order of Setne Khamuast, a Temple of Set order that Webb was then the grandmaster of. There doesn’t seem to have been any subsequent volumes to these proceedings, but what is presented here speaks to the order’s raison d’être of combining scholarship with magical practice. The blurb on the back of the book suggests a similar motivation, mentioning Webb’s hope that it will be “a partial antidote to the fuzzy thinking of the occult world,” – wonder how that turned out.

The other intention of The Seven Faces of Darkness, mentioned on the back cover of the book, is to reclaim the wisdom of Late Antiquity, and that is very much what we get here with a focus on authentic examples of Typhonian sorcery, principally from the Greek Magical Papyri. Before getting to those examples, though, Webb begins with a personally-voiced introduction and then provides a broad overview of the source material, focusing, by way of an early example, on three representative rituals: two from papyri (one in Greek and the other in both Greek and Demotic) and one from a curse tablet found in a well in the Athenian Agora. For each of these, Webb highlights how they relate to Set, in particular his syncretisation with the Greek figure of Typhon, a natural figure to appeal to when performing maleficia.

In the third chapter, Webb does a slight jump back by regrouping and focussing on Set; almost introducing him anew despite referring to him multiple times in the previous chapters. He gives a brief history of Set, beginning with what traces there are in the predynastic period and culminating with more recent events deemed significant, like the founding of the Church of Satan, Michael Aquino’s reception of The Book of Coming Forth By Night in 1975, and a Temple of Set heb-sed festival, under the guidance of the Order of Setne Khamuast, in Las Vegas in 1995. Webb then discusses attributes and symbols of Set, and considers his role in three locations: in the Duat, on earth, and in the sky; a fairly standard tripartite cosmological division.

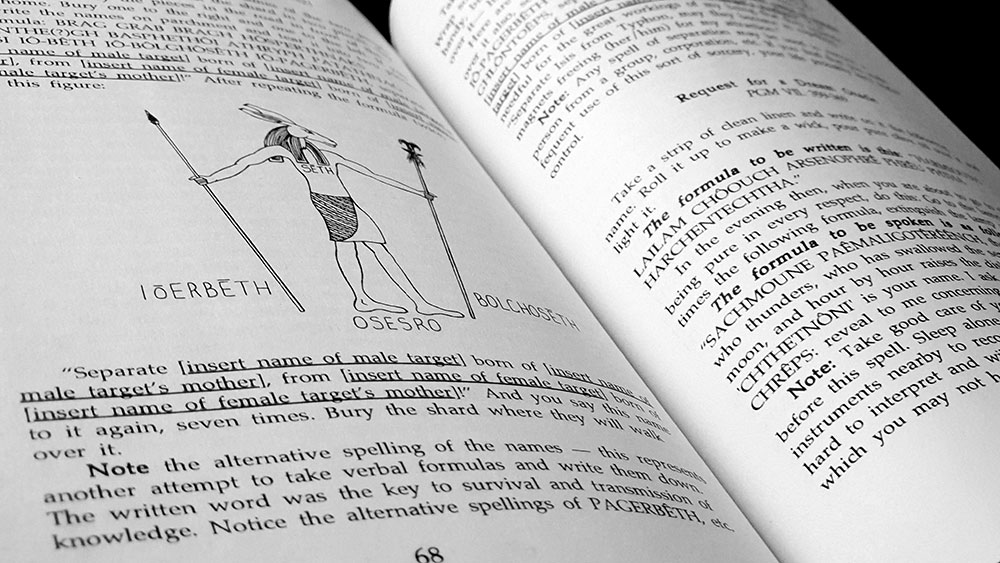

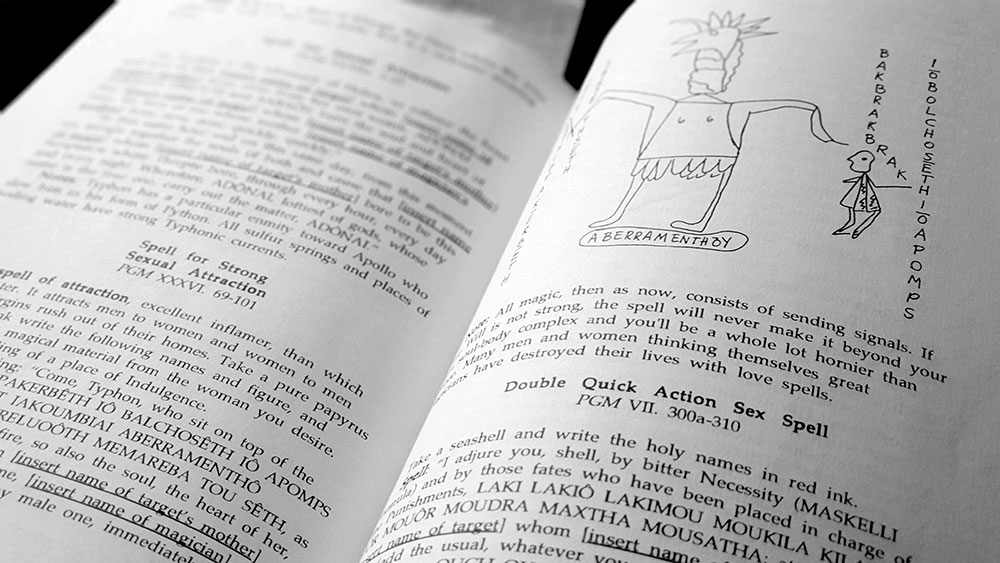

The largest section of The Seven Faces of Darkness contains a selection of spells from the Greek Magical Papyri and a few other sources, which are presented, one assumes, verbatim, usually with a note from Webb at the end. These spells, for the most part, cover the kind of things you come across in any compendium of folk magic, with formulae for creating sexual attraction, breaking up relationships, and restraining enemies. While some of these are only tangentially related to Set, others, though, have a particularly interesting Setian emphasis, such as the Spell for Obtaining Luck from Set from PGM IV 154-285. Here, the practitioners both summons and identifies themselves with Set, describing all of Set-Typhon’s activities as their own. In so doing, it provides a rich Setian liturgy, with Set addressed in all manner of evocative terms.

At just over 100 pages, The Seven Faces of Darkness should feel like a brief volume, but it’s surprisingly detailed. There’s the discussion of Set providing a good cosmological base, another chapter dealing more with modern Setian magickal theory and a guide to ritual, and then the exploration of the various spells from the PGM, which gives examples of genuine Typhonian sorcery and provides a toolkit of forms, tools and techniques drawn from Hermeticism and its Egyptian syncretism that can be adapted for personal use. As such, The Seven Faces of Darkness feels a little bit more essential as a guide to both Set and his magick than the recently reviewed Set: The Outsider. The exploration of Set from a mythological perspective while detailed is not that extensive, but it provides enough for anyone not familiar with him as a neter to get a sense of his complexity. Similarly, Webb’s discussion of ritual hits a lot of useful beats when it comes to setting up a system of magical praxis, including a listing of tool, several ways to approach working with Set, and a schema of festivals to celebrate throughout the year. This worth is somewhat hidden by the formatting, which is very utilitarian, so speaking of which…

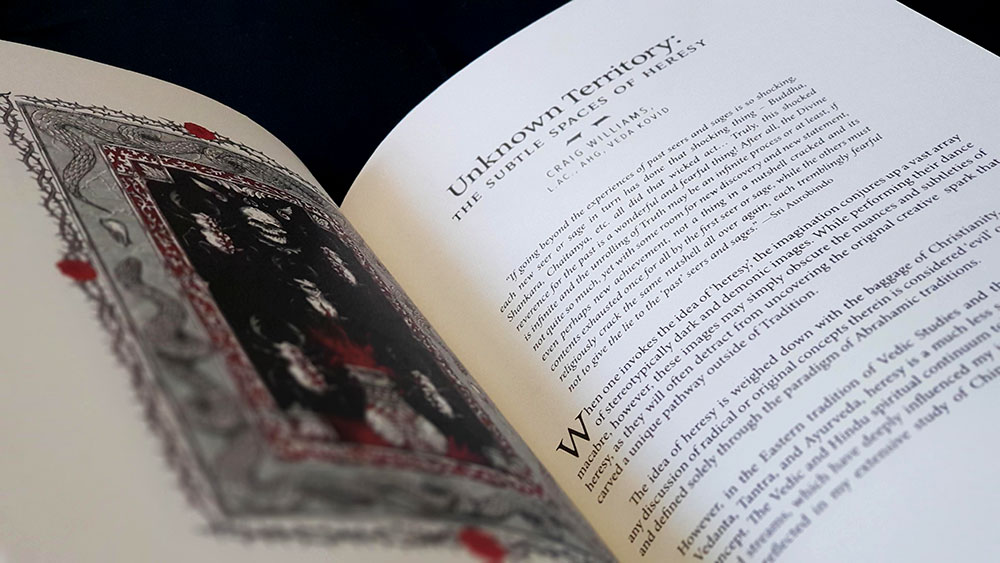

The Seven Faces of Darkness is formatted in Rûna Raven’s style of the times, which appears to have involved a sole rudimentary word processor. This means everything is messy and cramped with very little room to breathe. Ugly, archaic underlining is used for emphasis and everything (paragraphs, first paragraphs, subtitles, block quotes) have a first line indent. It’s those now atypical underlines that are the worst though, cutting thickly underneath bits of text, but coming across, such is the brutality of their placement, as if they are strikethroughs correcting copy.

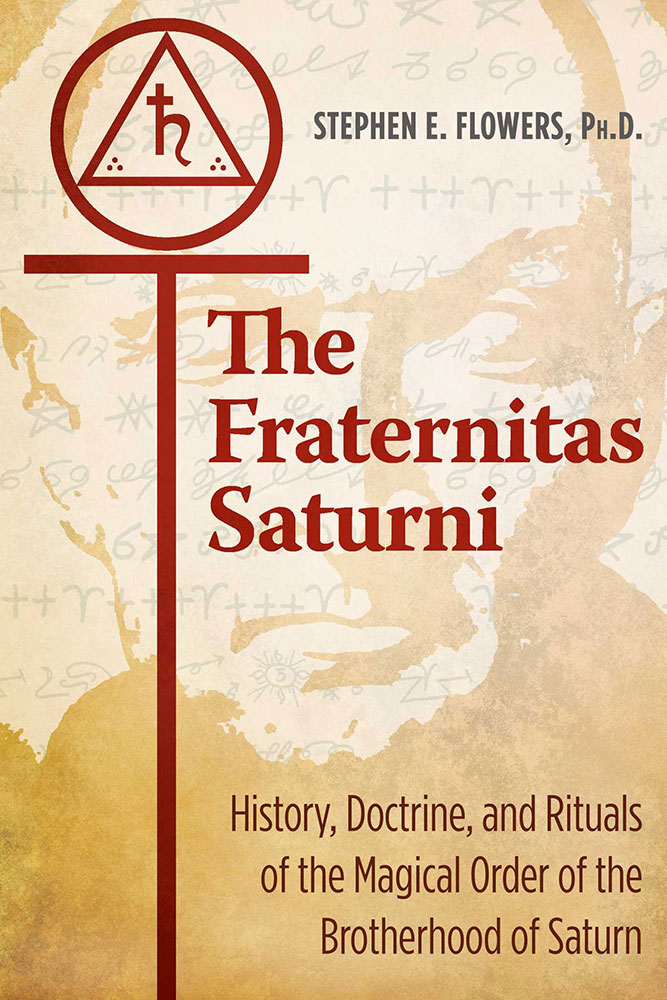

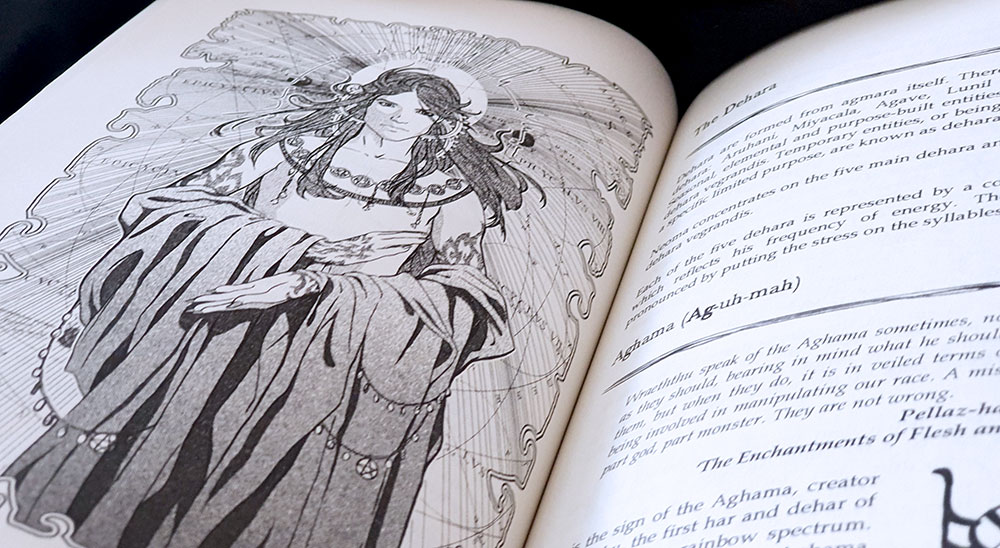

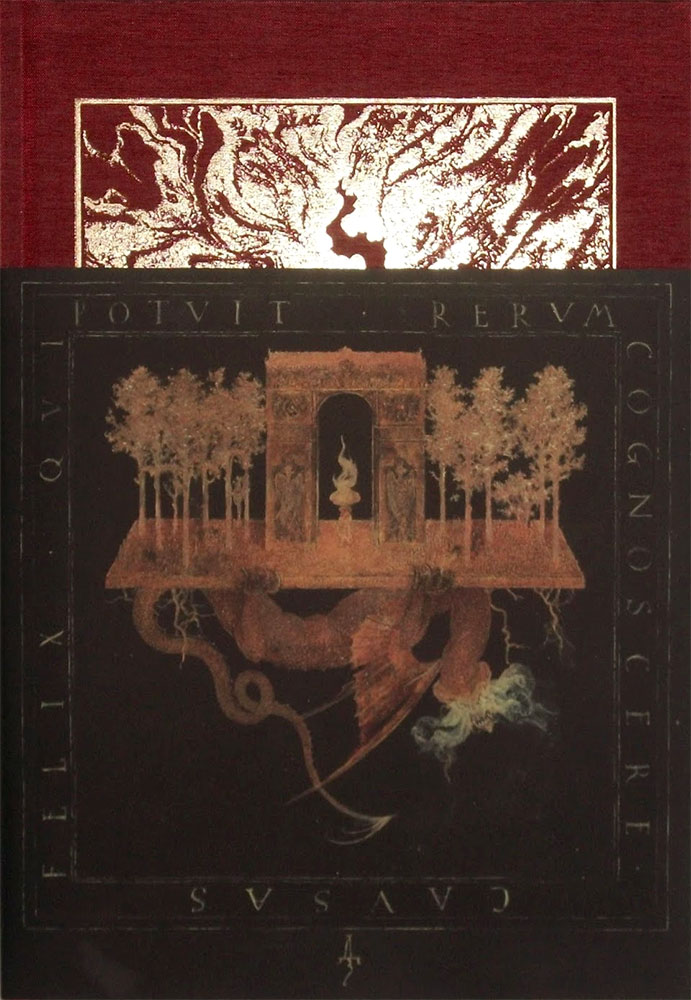

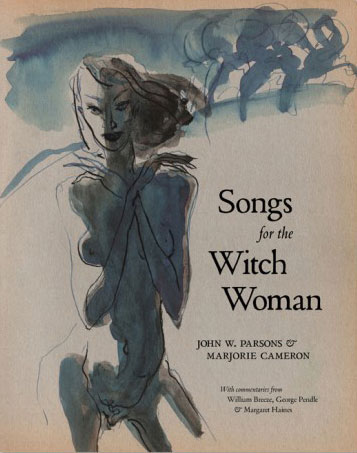

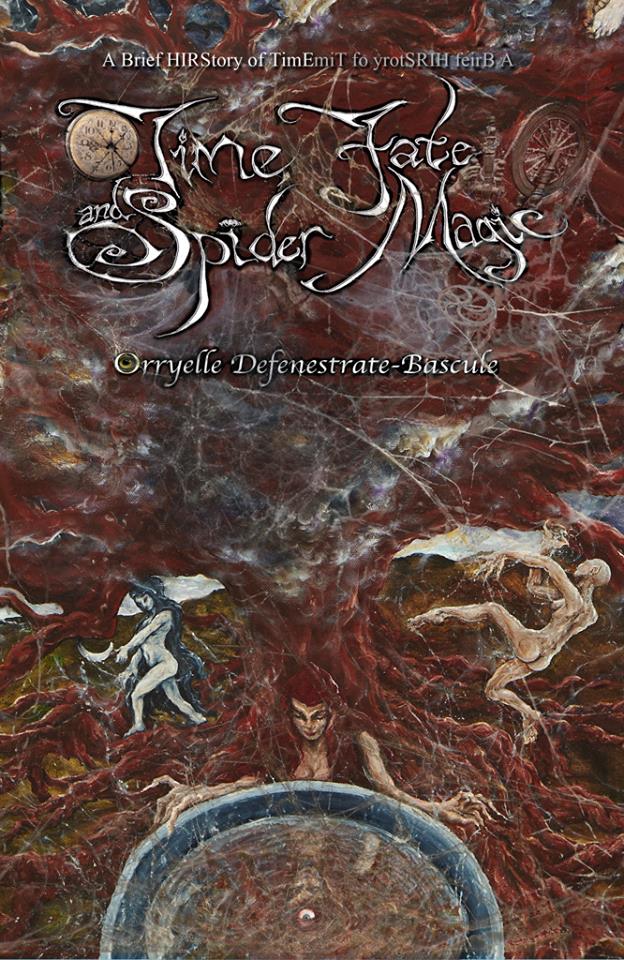

The cover design by Timothy Weinmeister (who also contributes some select internal illustrations) features a striking image of Set against a pyramid and temple peppered horizon. The reproduction, though, is soft and regrettably, it’s clear that a high resolution version of the artwork wasn’t used.

Published by Rûna Raven Press.