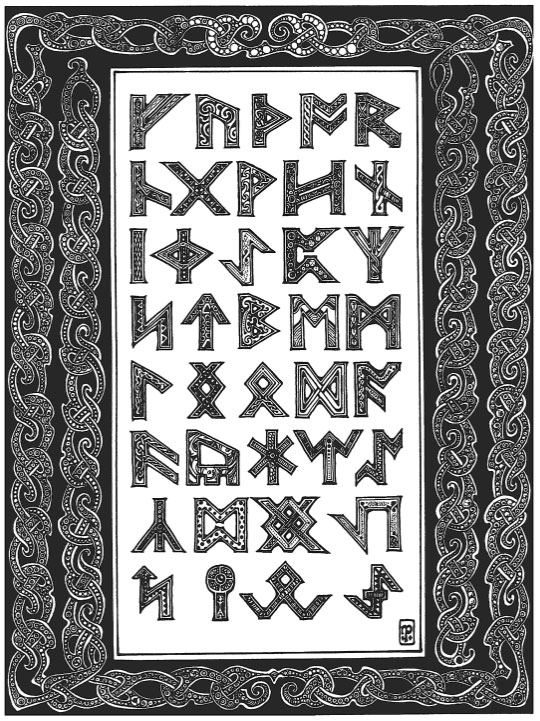

Bearing an unremarkable title that makes it somewhat merge with other seiðr-denominated books, Seiðr Magic is a how-to guide to reconstructionist Norse-inspired divination and trance. Putting aside the seiðr aspect, it follows the formula of many other popular occultism books, particularly of the Norse variety. There’s a basic outline of the history of the magical forms, a section on nomenclature and terms, another on tools, and the de rigueur detailing of the nine worlds of Norse cosmology, all set out in ten chapters, one building ‘pon ‘tother. The only thing missing, mercifully, is a chapter on the runes with the usual guaranteed page-count-inflator of interpretations and meanings.

Bearing an unremarkable title that makes it somewhat merge with other seiðr-denominated books, Seiðr Magic is a how-to guide to reconstructionist Norse-inspired divination and trance. Putting aside the seiðr aspect, it follows the formula of many other popular occultism books, particularly of the Norse variety. There’s a basic outline of the history of the magical forms, a section on nomenclature and terms, another on tools, and the de rigueur detailing of the nine worlds of Norse cosmology, all set out in ten chapters, one building ‘pon ‘tother. The only thing missing, mercifully, is a chapter on the runes with the usual guaranteed page-count-inflator of interpretations and meanings.

Dean Kirkland opens with an introduction, setting out what seiðr is, how it might be compared to shamanism, and what it is not. There’s a giddy enthusiasm here, one that defines seiðr by what it is not almost as much as what it is. To do this, Kirkland evokes the spectre of contemporary “Norse witches” (his persistent sneer quotes, take that!) who get it all so wrong, what with their historical inaccuracies. He goes so far as to imagine a four line rebuttal that such a strawmanwitch might respond with when challenged on their use of ahistorical things like casting magic circles and calling the elements. But he does them dirty by assuming they’d just say what amounts to “OK, how you know?” According to Kirkland, these “Norse witches” believe that tarot was being used by their ancient antecedents, which if they really think that, and weren’t simply fulfilling their fictional role in this fallacious scenario, is a belief so laughable as to not warrant a snarky mention in the introduction of your book. It’s almost as if the reconstructed nature of the seiðr presented here needs to pre-empt any criticisms by mentioning a much worse reconstruction. “Yeah, I might have made this up, but at least I didn’t include tarot like those fakers.”

In the ten chapters of Seiðr Magic, Kirkland breezes along at a fair clip, presenting his version of seiðr in a very palatable, modern-pop-occultism manner that is generally correct but low on citation, with Neil Price’s The Viking Way being the only Norse academic text to get a mention. As a result, everything can end up feeling just a little untethered and ‘trust me, bro’. Things are consistently compared to shamanism, and while Kirkland does give some specific examples, too often the language used refers simply to “shamans all around the world” or “most shamanic cultures” and the like, flattening diverse and geographically distant cultures into one amorphous analogical device. The list of cited works bears these impressions out, with a short crop that, other than primary Norse sources, is limited to Price’s The Viking Way, Mircea Eliade’s Shamanism, Michael Harner’s The Way of the Shaman (unsurprisingly), The Norse Shaman by Harner student Evelyn C. Rysdyk, an article from the shamanism magazine Sacred Hoop, two books by Edred Thorsson, and, somewhat disproportionately, three folklore books by Claude Lecouteux. No academics were harmed (or encountered) in the writing of this book; with apologies to Professor Price. In all, what is presented here is largely inoffensive, just very smoothed over, occasionally vague and awash in the type of framing one might expect from a New Age-adjacent imprint like Destiny Books.

In chapter seven, Kirkland strays specifically from seiðr, something which he acknowledges in the preamble, and looks at hearth and land spirits. Strangely, while this includes a discussion of Landvættir (the Norse spirits of the land), a larger section is on the Cofgodas, whose Anglo-Saxon derivation makes for quite the startling etymological aberration amongst all this Old Norse. This is made all the stranger since the historical use of cofgodas to refer to household gods is so slight as to be practically non-existent, with the word only occurring in Old English texts as a gloss for the Latin penates (the dii familiares or household deities of ancient Rome). Other than acting as a post-Christian gloss for a Roman concept, and one which was probably invented solely for that editorial role, there’s no evidence of the cofgodas in Anglo-Saxon paganism. It was Claude Lecouteux who really took the name and ran with this idea of cofgodas as household spirits, arguing that they were akin to the kobolds of medieval German legend (who, it must be pointed out, are mischievous sprites rather than minor gods), and making much from so little. The self-replicating, fact-checking-averse nature of the interwebs has then further uncritically perpetuated this idea. Unsurprisingly, Lecouteux’s 2013 The Tradition of Household Spirits is cited here by Kirkland and seems to be the sole source of the information.

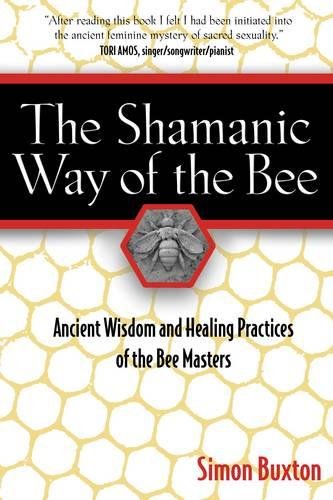

Kirkland is described in his biography as a goði of the Three Castles Kindred, and a part of the “ritual-specialist team,” whatever that means, for Asatrú UK. He has a Ph.D in ecology (or entomology according to his LinkedIn profile) and also mentions undertaking a shamanic apprenticeship with the Dorset-based Sacred Trust. The latter immediately sets off alarm bells as Sacred Trust is the organisation of fantasist and fabulist bee-botherer Simon Buxton, whose plagiarised book The Shamanic Way of the Bee has been previously (and scathingly) reviewed on this site. Such deceit makes suspect anything else associated with a serial maker-of-things-up such as Buxton.

Speaking of making things up, in his introduction, Kirkland references the use of Unverified Personal Gnosis (UPG) in his practice and says that any examples will be identified as such in the book whenever possible. The ‘whenever possible’ caveat seems warranted as it was apparently not always possible to do so. While Kirkland often backs up what he’s saying with recourse to primary textual sources, at other times he’ll just throw something out there as if it is uncontested or accepted, filling in little lore gaps without identifying them as the mytho-polyfilla that they are. In discussing the nine worlds, for example, he associates each realm with a guardian, and makes the interesting claim, one that doesn’t exist even remotely in lore, that the guardian of Niflheimr, what with its icy associations and all, is the king of the rime thurses, adding the caveat that the specific holder of this title can sometimes change. He makes a similar claim for Svartálfaheimr, and this time the guardian is the current king of the dwarves, a position that apparently “due to internal politics” can change from time to time. Cool story, bro.

There are also a few bits of odd and errant etymology, which is strange as most of what is here otherwise hews to the standard. When listing the names given to various types of magical practitioners, he dissects the title Galdrakona to mean ‘woman that crows’ rather than the obvious ‘spell woman.’ Injudiciously extrapolating on a single line from Edred Thorsson’s 1993 Rune-Song: A Guide to Galdor (in which he traces galdr back to galla), Kirkland claims that galdr is “literally translated” as the “cawing of crows” or “crowing of cockerels,” seemingly mistaking galdr (‘magical chanting’) for galla (to ‘sing,’ ‘chant,’ and yes, to ‘crow’). Whilst related, galdr is not galla (having distinct Proto-Germanic roots: galdraz and galan? respectively) and, as it is, both are words that still prioritise the idea of galdr as an empowered vocalisation, with any avian crowing associations being at best tertiary. That galla can be used for the voice of birds means nothing when it’s also applied to the voice of anything else (wolves, Loki, your mum). Also, getting crow (kráka) the bird from crow (galla) the action in order to extrapolate galdr into the ‘literal’ “cawing of crows” is quite a linguistic leap and one that seems to rely on the homophonous nature of only the English version of the words. Taking this idea to its ‘literal’ conclusion, the use of galdr as a general term for all types of Norse magic must have meant that anytime someone was alleged to have performed magic, they were really being accused of talking like a chicken? Was a galdramaðr a chicken-talking man? Was their galdrabók a chicken-talk-book? A squawkbook?

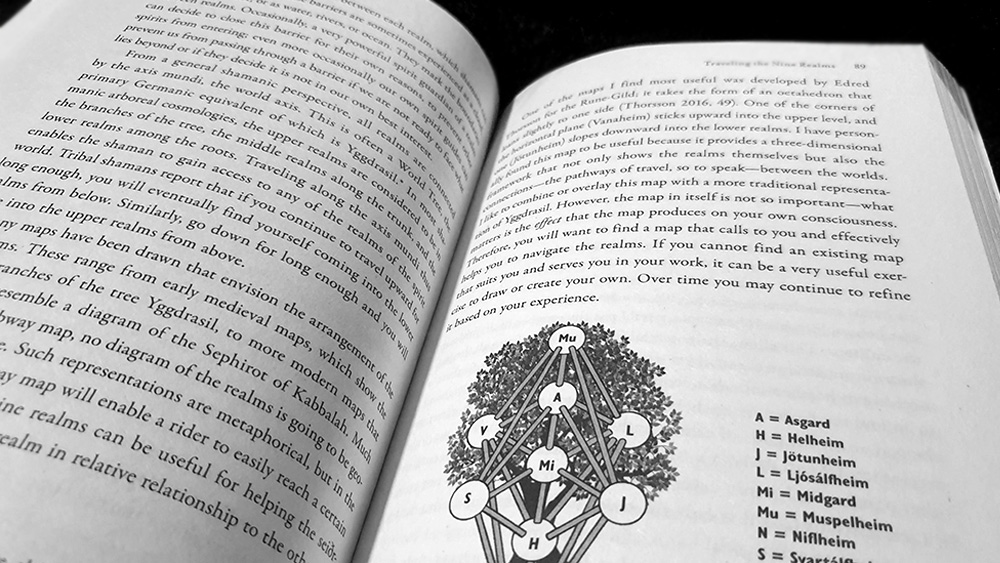

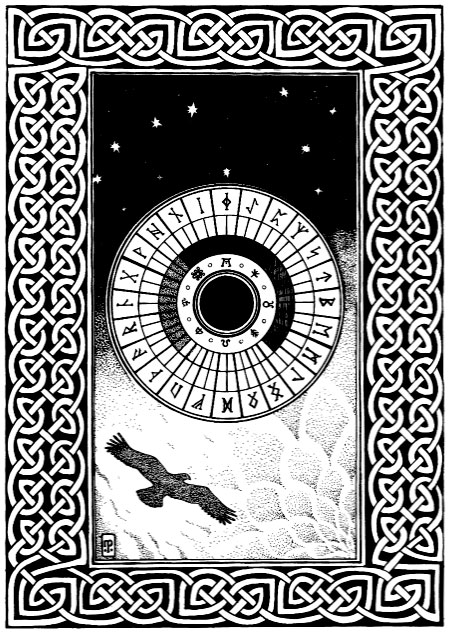

The text and layout for Seiðr Magic has been handled, as is tradition, by Debbie Glogover, with body set in old favourite Garamond, whilst Gill Sans, Mrs Eaves, and Swear Display are used as display faces. The formatting is light and breezy, with a generous leading between lines that near doubles the page count, pushing it a little past 200. Illustrations are limited to a diagram of the nine worlds (a schema formulated in the style of Stephen Flowers), and two small and murky photographs of Kirkland’s seiðstafr which really weren’t worth the effort.

Published by Destiny Books