Hekate is a goddess with no shortage of books about her, and the shelves here at Scriptus Recensera do not want for her tomes, whether it’s Robert von Rudloff’s Hekate in Ancient Greek Religion, Sarah Iles Johnston’s Hekate Soteira or a veritable hoard of titles from Sorita d’Este and Avalonia Press. This isn’t even Ixaxaar’s first foray into Hekate’s world, stretching back to at least 2010 and Mark Alan Smith’s Queen of Hell. This surfeit of material is understandable given the wealth of classical source texts available concerning Hekate (clearly the deepest repository of data for any of the darker-hued goddesses), and also her aesthetics which have an almost innate appeal for those with, how you say, more cimmerian proclivities.

Hekate is a goddess with no shortage of books about her, and the shelves here at Scriptus Recensera do not want for her tomes, whether it’s Robert von Rudloff’s Hekate in Ancient Greek Religion, Sarah Iles Johnston’s Hekate Soteira or a veritable hoard of titles from Sorita d’Este and Avalonia Press. This isn’t even Ixaxaar’s first foray into Hekate’s world, stretching back to at least 2010 and Mark Alan Smith’s Queen of Hell. This surfeit of material is understandable given the wealth of classical source texts available concerning Hekate (clearly the deepest repository of data for any of the darker-hued goddesses), and also her aesthetics which have an almost innate appeal for those with, how you say, more cimmerian proclivities.

Now, after their recent release of Jack Grayle’s The Hekatæon, described by Ixaxaar as the first turning of a key to the kingdom of Hekate, a second key is turned with this book by the enigmatically named Idlu Lili Regulus. Originally released in Swedish in 2017 by Avgrund Förlag, Hekate: The Crossroads’ Dark Goddess is a smaller volume than The Hekatæon, but has certain similarities due to its combination of theory and ritual.

Hekate: The Crossroads’ Dark Goddess begins with little ceremony or preamble, diving straight into a discussion of Hekate’s ancestry and status as monogen?s, before expanding into a consideration of various mythical beings associated with her via birth or proximity. What one notices immediately is the surfeit of footnotes and citations, with primary sources and academic texts diligently cited at every utterance. Footnotes, meanwhile, are extensive, running to a paragraph normally, but occasionally stretching to half a page and in a few instances, almost an entire page.

This rigour makes for a satisfyingly academic feel, though it is one that provides moments of incongruity. While Regulus writes, for the most part, with a formal style befitting the citations and footnotes, they occasionally break into the more informal voice of a devotee. Thus, amid quotes from authorities ancient and modern, they will suddenly address you “the dear accursed reader” or wax effusively over a quote from Hesiod that causes their heart and being to “reverberate with its ancient, sacred and literally awe-inspiring tone.”

As this fervent tone suggests, Regulus does identify this book as a devotional, rather than an exhaustive or definitive treatment of Hekate, despite the thoroughness of the writing, citing and footnoting. What they choose to focus on, then, following the first chapter, are her associations with the moon and the underworld, and then things relevant to practical work with her: the plants associated with her, her many titles and names (predominantly drawn from the Greek Magical Papyri), and various documented classical examples of working with her.

Hekate: The Crossroads’ Dark Goddess concludes with an appendix of rituals that build upon the historical evidence that precedes them. These begin with a basic crossroads initiation (part meditation, part visualisation) and a heavily footnoted invocation of several pages, drawing on text from PGM IV. The rest includes brief instructions for circle casting (in which, interestingly enough, Cayn/Cain as the witch father is invoked alongside Hekate), a love spell of attraction, a graveyard communion and a crossroads supper, as well as a devotional Hymn to Hekate. In keeping with the tone of the rest of the book, these aren’t simply instructions with a ritual recipe to follow, but include pages of supplementary information documenting historical precedents, and even more within the footnotes.

As one might expect given the publisher, there’s an element of anti-cosmic philosophy that occasionally rears its serpentine head, with Regulus, for example, regarding the famous Gigantomachy frieze from the Pergamon altar as a depiction of a factual attack by the anti-cosmic Titans against balanced cosmic order’s temporary reign. This is by no means pervasive, and Hekate herself isn’t gratuitously presented in anti-cosmic terms, but it is something that subtly informs what is presented here.

Regulus writes in a confident, sometimes strident, manner, weaving together the slightly academic with the demonstrably devotional, and using turns of phrase that belie the text’s non-English origins. There is no credit for the translation from the original Swedish but it is satisfactory in its execution. There are the occasional awkward sentences where, for example, the tense can slip, but not to a detrimental degree, and by no means as bad as some occult works from native English speakers.

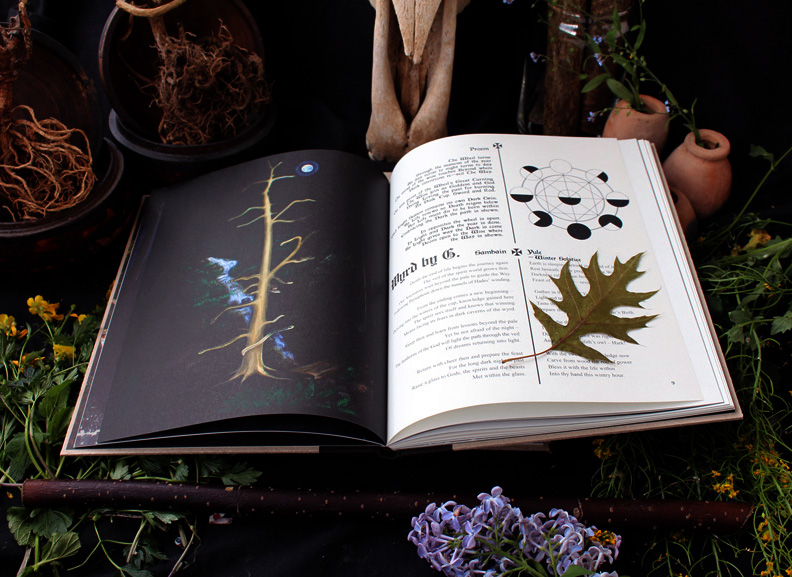

Hekate: The Crossroads’ Dark Goddess is laid out capably, with body in a clear and classic serif, sitting within generous but not excessive margins. Headers, both main and sub, are rendered in the all caps of a different, slightly irregular, serif face, while chapters begin with a fetching drop cap from the same blackletter face used for the cover and title page. There are, though, a few too many widows and orphans, and shorter quotes are too often separated into their own paragraphs, looking bitsy when buttressed above and below by paragraph spaces, even when they’re only a single or even partial sentence; whereas convention would have them incorporated into their preceding paragraph.

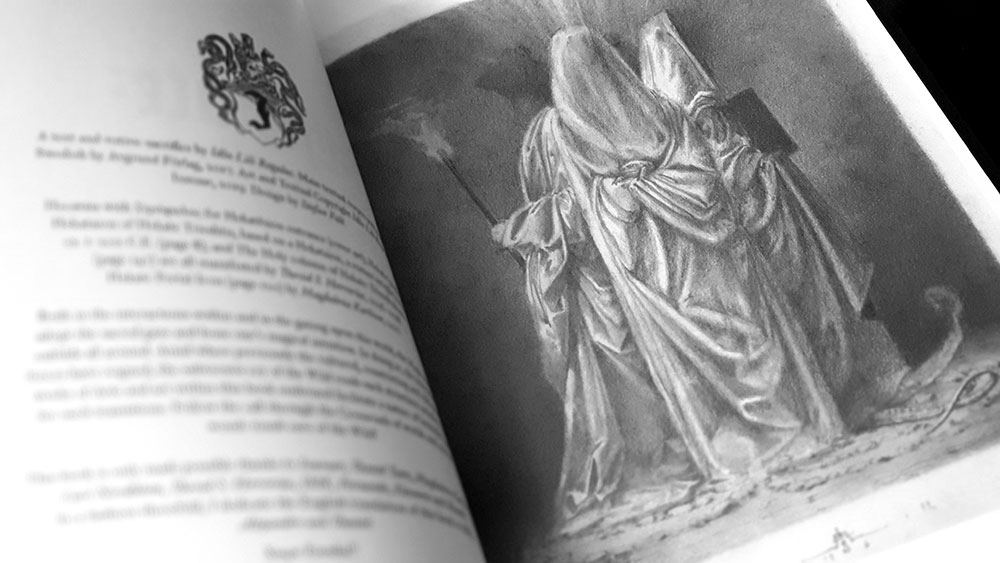

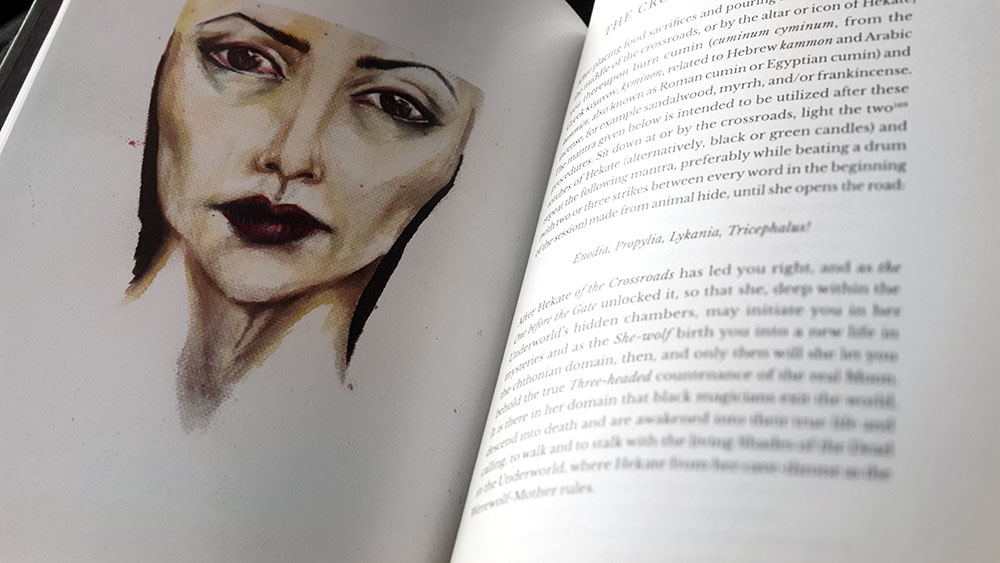

Illustrations in Hekate: The Crossroads’ Dark Goddess are sparse with no in-body images of any kind and only a few full page illustrations, including glossy plates with an image of Hekate by the always reliable David Herrerias at the start, and a painting by Magdalena Karlsson, Hekate Portal Icon, leading the ritual appendix.

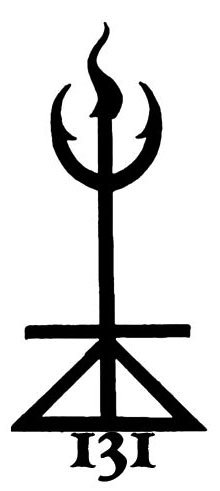

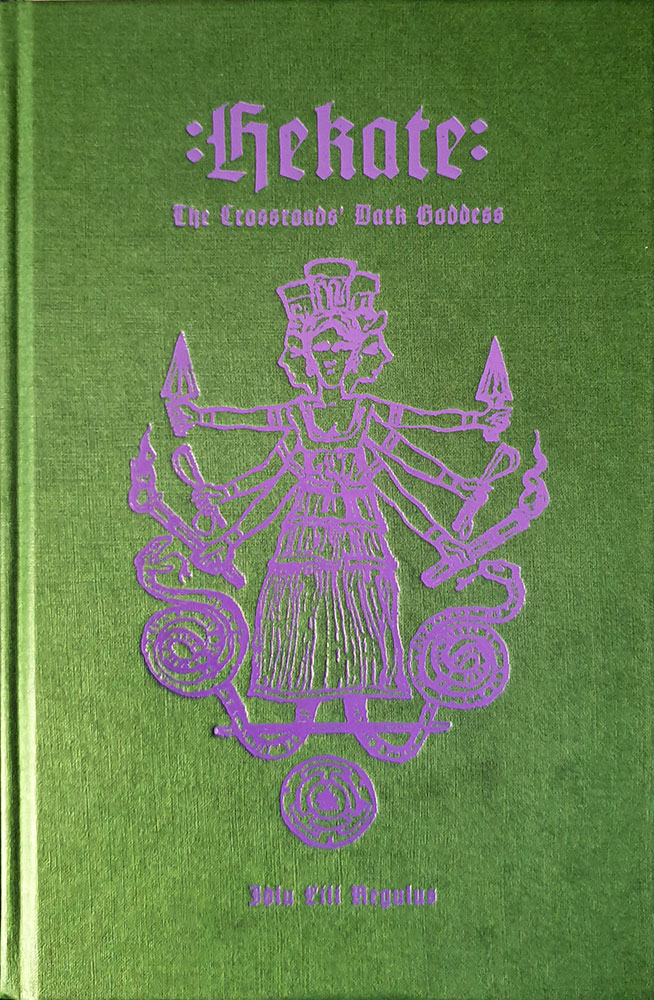

The regular edition of Hekate: The Crossroads’ Dark Goddess runs to 480 copies and is bound in green cloth with title and an image of Hekate (a familiar Hekataia with her depicted three-headed and multi-armed, holding a variety of implements) debossed in a hard-to-read-in-low-light purple. The book was also made available in a special edition of 70, housed in an amethyst-coloured slipcase with an image of Hekate-Zônodrakontis foiled in silver on the front and back. Also included in this edition is a medium-size art card with the image of Hekate by David Herrerias, measuring 26.6 by 20.7 cm and printed on high quality glossy cardboard.

Published by Ixaxaar