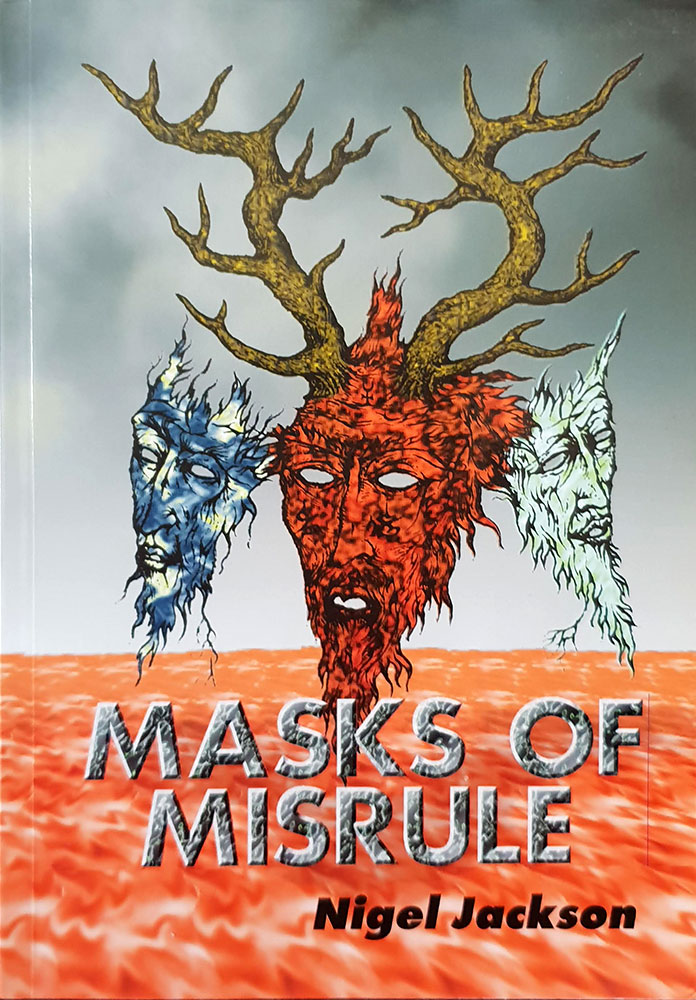

Over the years here at Scriptus Recensera we have retro-reviewed a number of traditional witchcraft and occult titles produced by Capall Bann. With the exception of a few outliers, this is the final piece in a body of related works produced variously, sometimes individually and sometimes in collaboration, by Michael Howard and Nigel Jackson. While other titles from these two authors have dealt specifically with what could be called witchcraft, The Pillars of Tubal Cain takes a slightly more divergent track, considering angelic magick, but pursuing it in a way that is resolutely conscious of how it relates to witchcraft, and in particular those variants of said craft that are described as dual observance, in which Christian cosmology provides a mythological framework.

Over the years here at Scriptus Recensera we have retro-reviewed a number of traditional witchcraft and occult titles produced by Capall Bann. With the exception of a few outliers, this is the final piece in a body of related works produced variously, sometimes individually and sometimes in collaboration, by Michael Howard and Nigel Jackson. While other titles from these two authors have dealt specifically with what could be called witchcraft, The Pillars of Tubal Cain takes a slightly more divergent track, considering angelic magick, but pursuing it in a way that is resolutely conscious of how it relates to witchcraft, and in particular those variants of said craft that are described as dual observance, in which Christian cosmology provides a mythological framework.

According to information posted by Howard, the book was begun by Jackson, with a few draft chapters then sent by the publisher to Howard who completed the majority of the book when Jackson discontinued his involvement. In an Amazon review, Jackson has repudiated this book and his role in it, apparently finding the sulphurous whiff of diabolism a little too embarrassing in his advancing years. Twice he speaks of it as something of a youthful folly, referring dismissively to his “occultist period” and describing the book’s core ideas as a result of the “entertainingly sensationalistic, but intrinsically illusory and misleading, vagaries of the 1960s-70s occultism” which he had imbibed in his wayward youth. While it’s easy to be a little embarrassed by what one may have written in the past (this writer certain has been), one feels a little suspicious of the complete 180 degree pivot here, especially when what was once apparently believed is now to be so contemptuously spoken of. The tone carries with it all the enthusiastic vitriol tinged with regret that one would expect of a new convert or a remorseful addict, and sees a struggle to replace the embracing of dark glamour with its inverse, a self-righteous and sanctimonious dismissal.

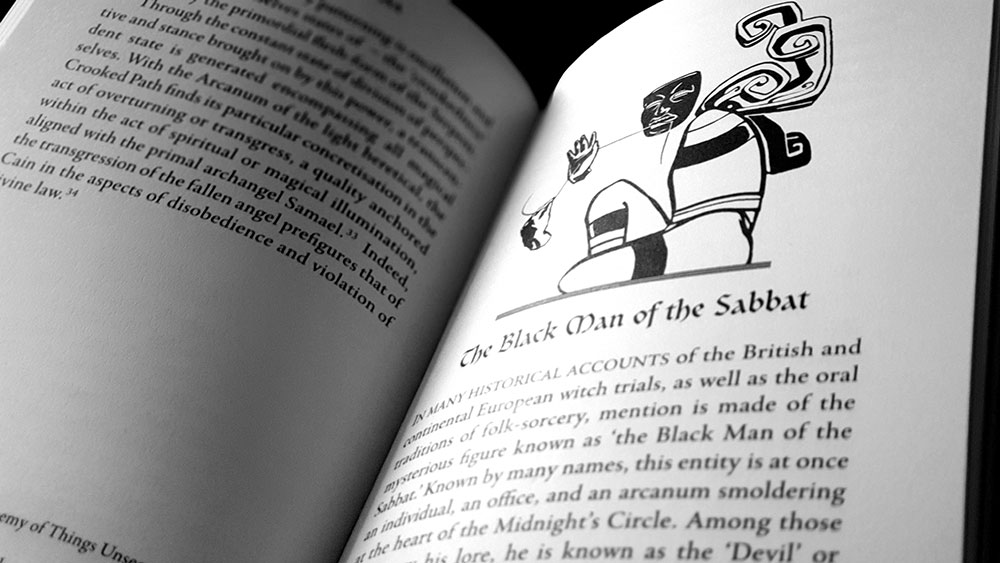

Amusingly, some other Amazon reviews suggest that this is a book that has often quite inexplicably found its way into the hands of people of a certain sensitive and easily spooked disposition, with one person describing it as a “sick and vile book” and another, rather grandly, as “a book of pure evil.” I do wish it lived up to that promise, but it’s not even close; evil perhaps, but pure evil, really? Let’s not overdo it. Oh to be the easily empathic type who finds demonic energies dripping from books and irrevocably impacting their lives, when I see only mere paper and ink; it must make life so exciting, if a little tiring. Indeed, while there is a fair bit of the demonic here, it’s of the type that would only be shocking to the kind of person who thinks a company playing with cutely devilish imagery in its branding is practically opening the gates of hell and welcoming damnation for all. Not only that, but in comparison to more specifically sabbatic-style titles, the focus here is on a slightly more palatable Lucifer, with his angelic siblings, fallen or otherwise, giving the Lightbearer an air of respectability.

The Pillars of Tubal Cain follows the formula found in its companion titles with a deep dive into a lot of information, all collected together in an exhaustive but not necessarily rigorous or overly discerning manner. References to particular named sources can sit alongside speculation or an anonymous appeal to authority where a generalised and unnamed ‘some’ or ‘tradition’ is seemingly given as much credence as their named equivalent. Howard and/or Jackson begin with a survey of various forms of belief in the Middle East that show certain atypical interpretations of the Abrahamic religions, suggesting, more often than not, a certain commonality with or continuity between Sabeans, Zoroastrians, Nestorian Christians, Yezidis, various Gnostic or Hermetic strains of thought, and others that have a sprinkling of Luciferian themes. The cascade of information can feel a little overwhelming, pulling as it does from a multiple of reference-less sources, and what emerges is a valuable overview of some roads less travelled, but one which you wouldn’t necessarily trust without checking in depth, if you can work them out, some of the primary sources.

This polymathic approach continues throughout the rest of the book, with the two Howard and Jackson meandering through various streams of esotericism, from Gnosticism and Qabbalah, to the Templars and Freemasonry, and to Arthurian lore and traditional witchcraft, highlighting particular gems that build a fairly convincing if sometimes circumstantial and insubstantial picture. Some of these stops along the way will prove familiar, to greater and lesser extents, to anyone acquainted with this particular oeuvre, specifically those strands of witchcraft that focus on Qayin, and obviously Tubal Cain, such as Robert Cochrane’s Clan of Tubal Cain, and Andrew Chumbley’s Cultus Sabbati. Interestingly, despite being a student of hers in the 1960s, Howard makes only brief mentions of Madeline Montalban, whose idiosyncratic and Luciferian magickal system aligns with much presented here.

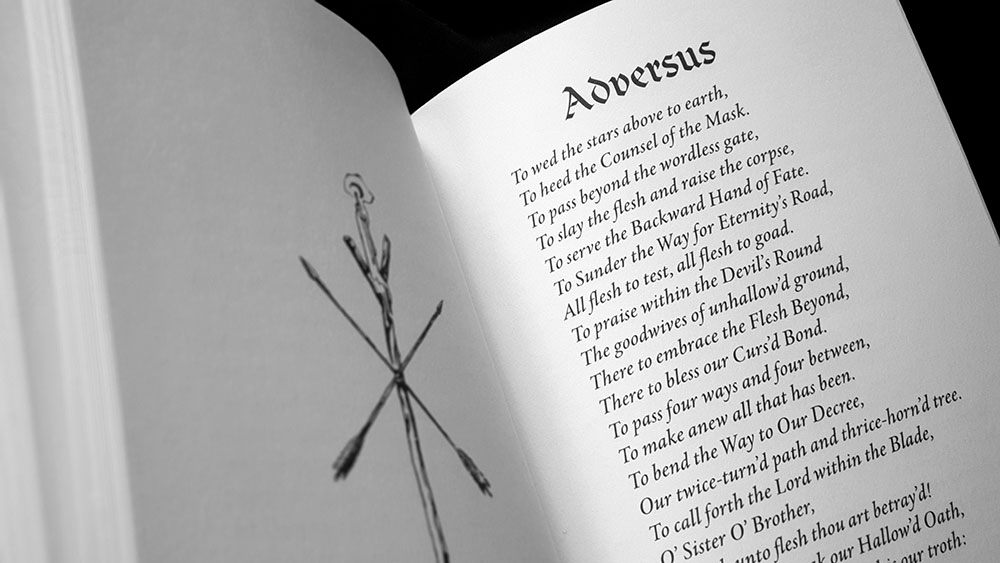

The Pillars of Tubal Cain concludes with a series of appendices, all from Jackson, save the first one in which Howard gives correspondences for eleven angels (Mikael, Gabriel, Raphael, Anael, Samael, Sachiel, Cassiel, Uriel, Asariel, Azrael and Lumiel) with instructions on how to contact them. Jackson’s contributions are a hymn to Hermes; a ritual invocation of Herodiana-Sophia-Epinoia deliciously called the Ceremony of the Peacock Moon; another ritual, this time a prose-heavy fire rite for Tubal Cain; a brief two page Gospel of Cain telling a more favourable and numinous version of Qayin’s story; and finally, an invocatory poem addressed to Lord Lumiel called The Baptism of Wisdom – making for what is a considerable liturgical body of youthful indiscretions.

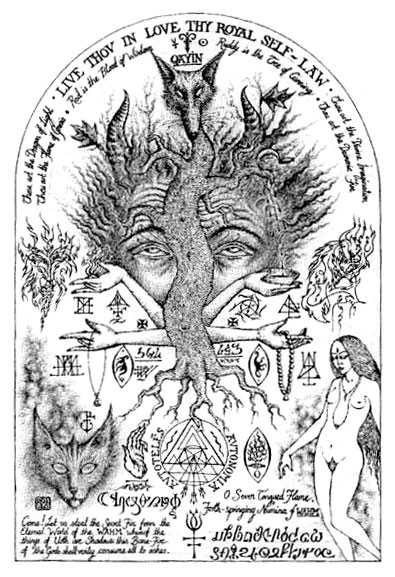

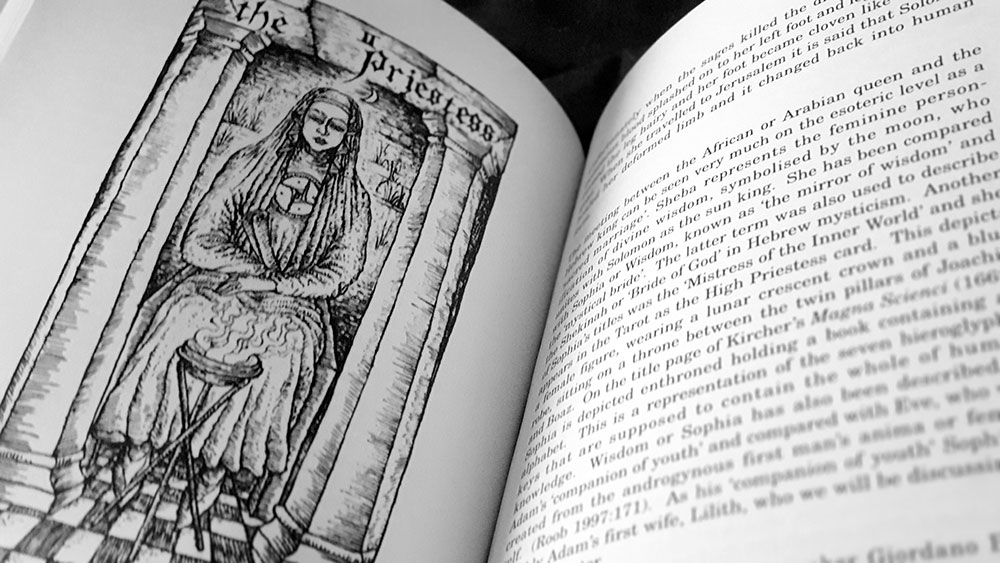

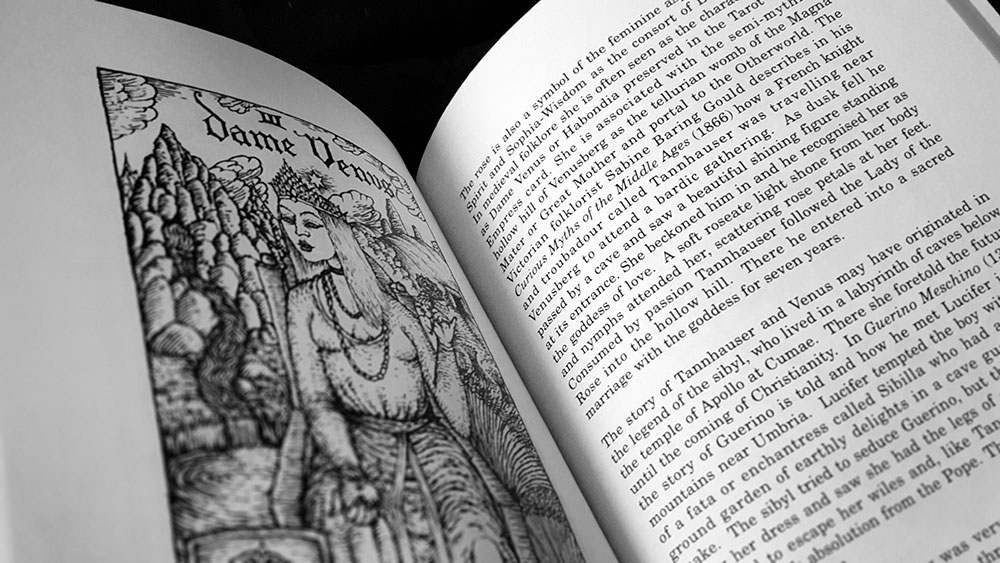

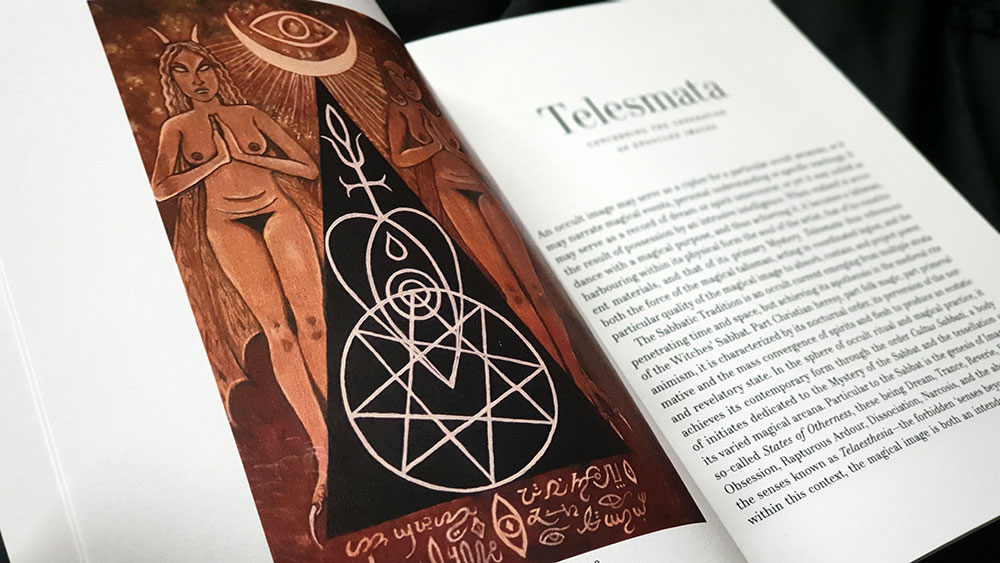

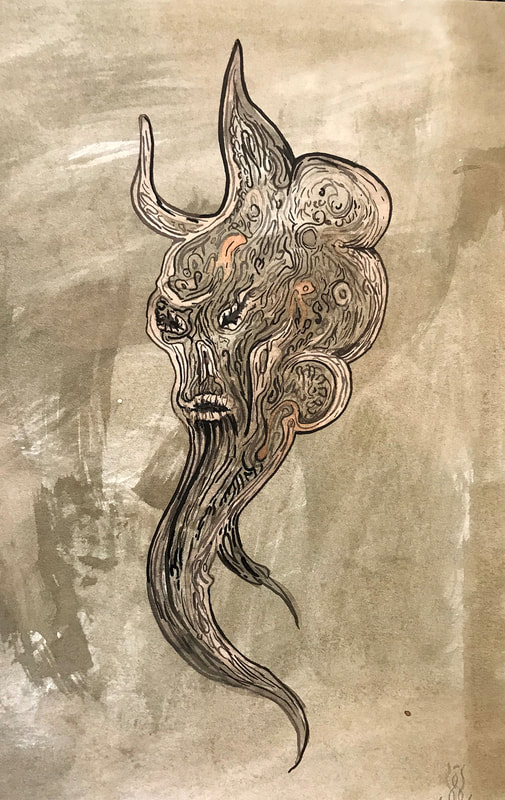

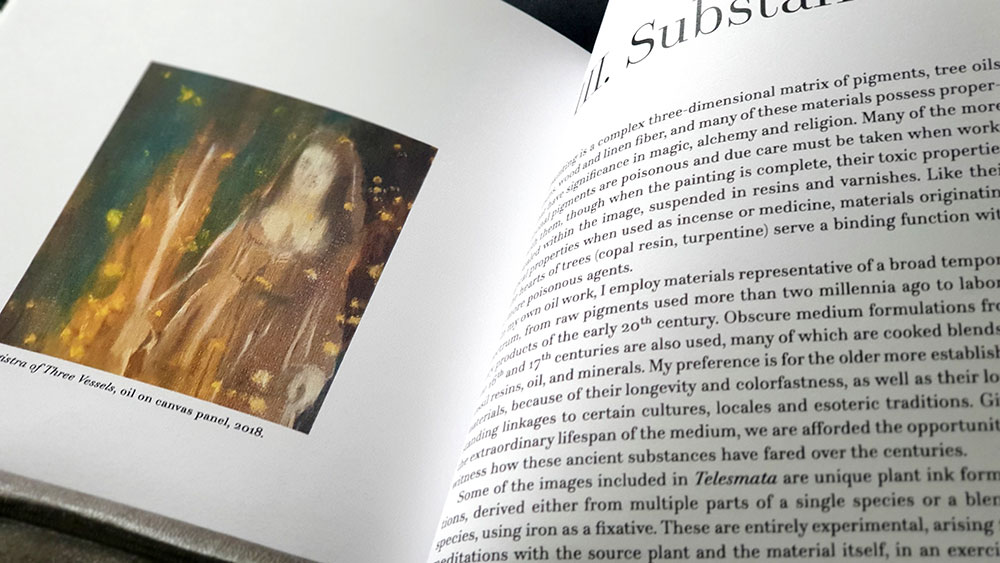

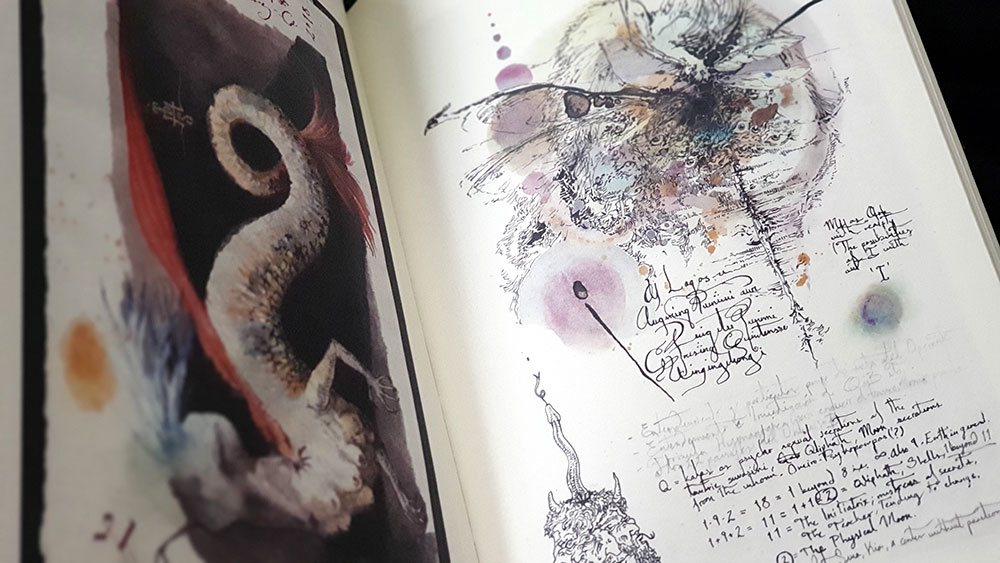

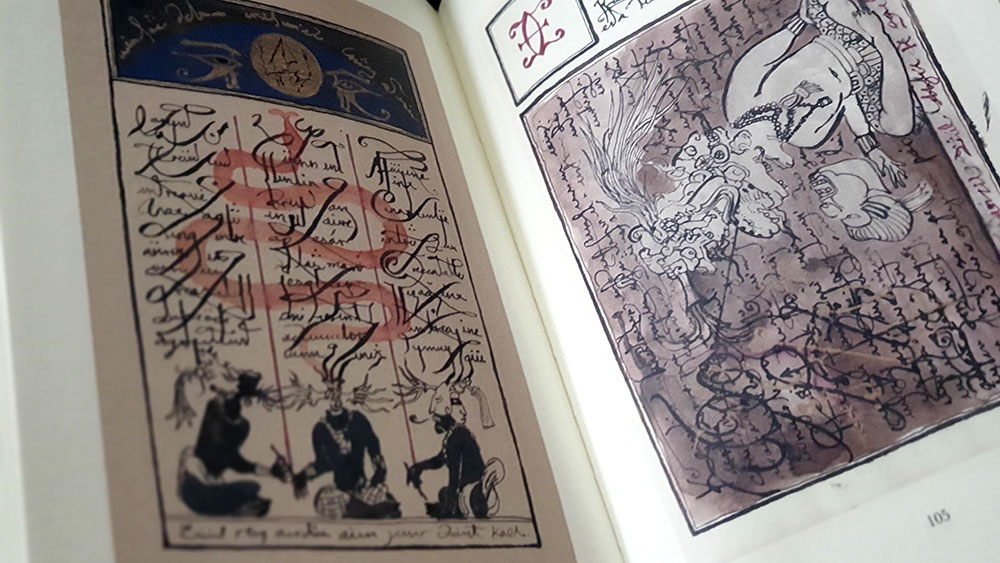

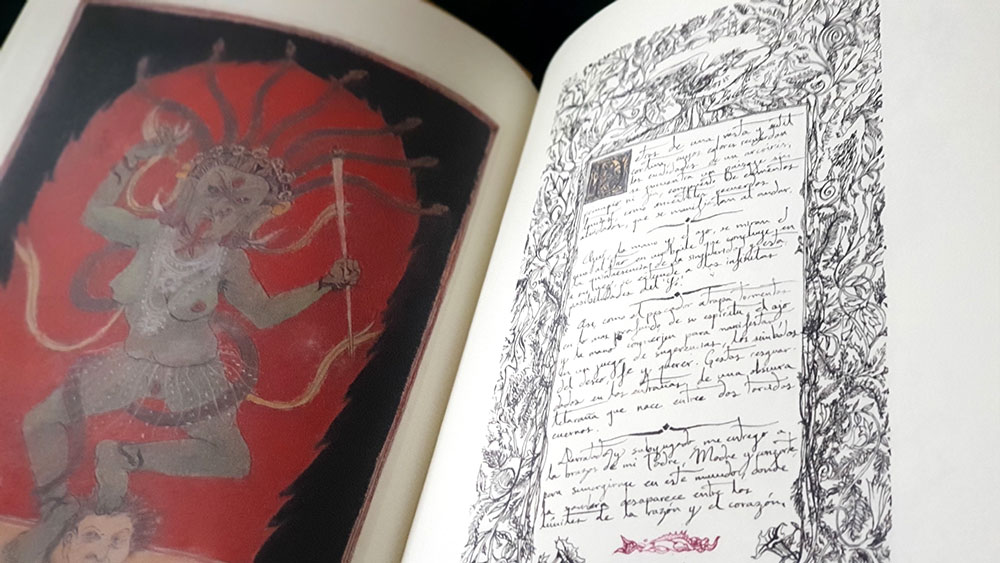

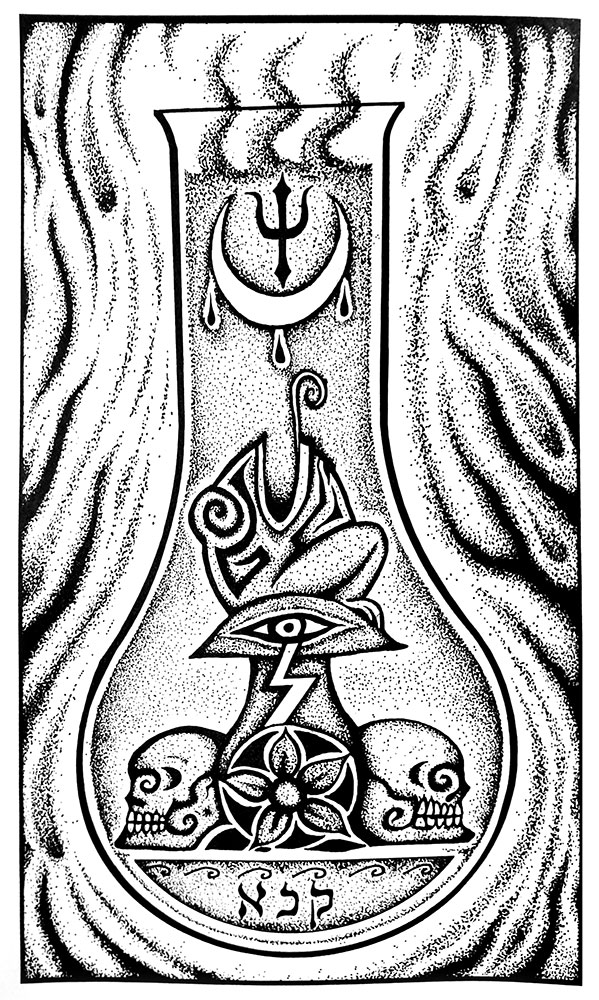

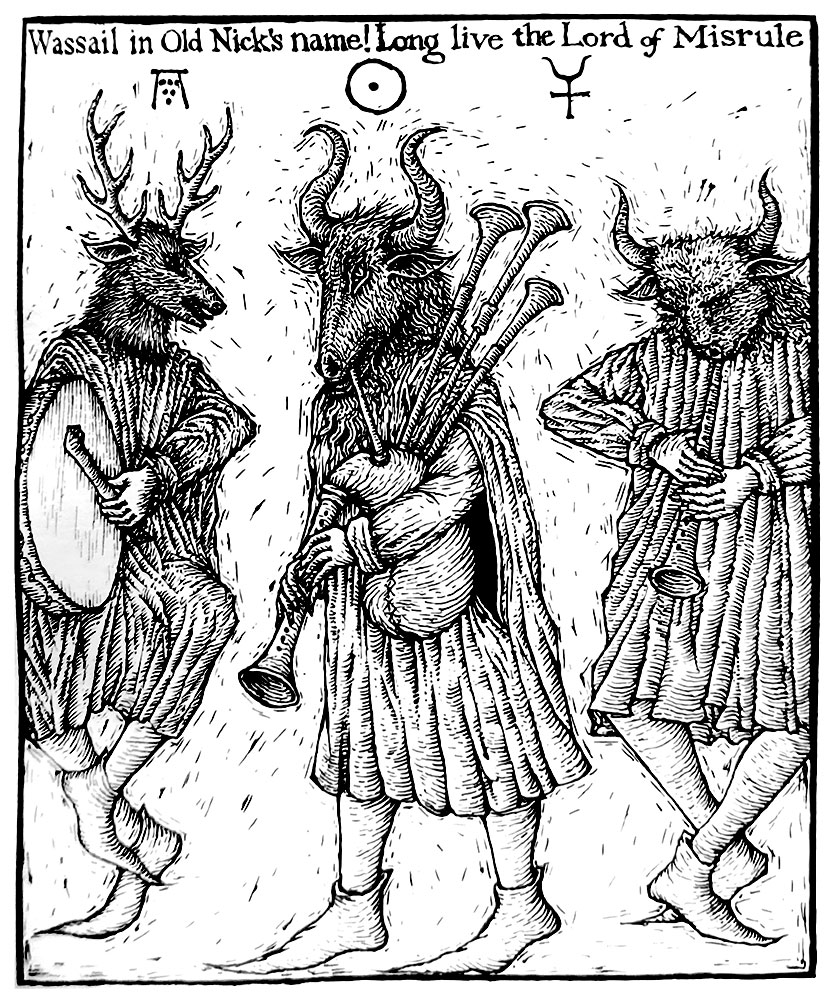

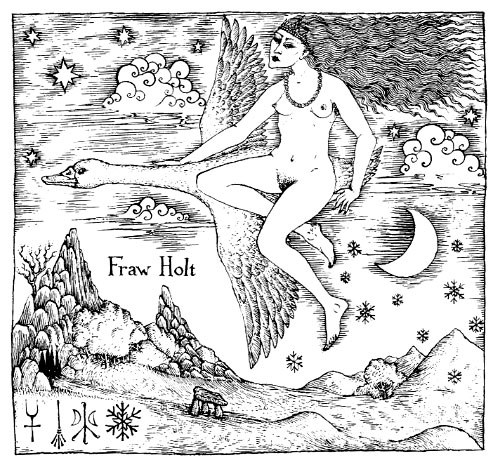

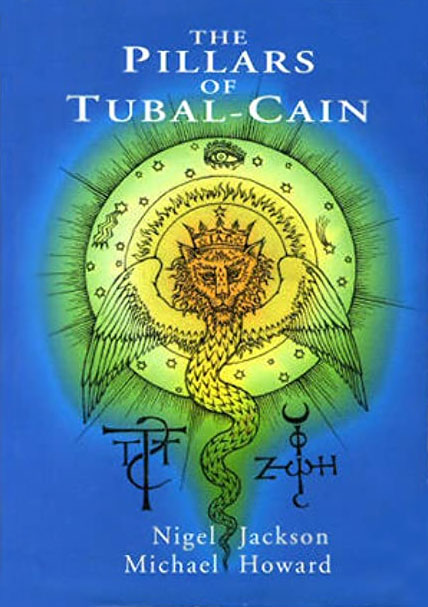

There’s a multitude of images throughout The Pillars of Tubal Cain, some with credits and some without, with some custom illustration and other, one assumes, public domain images of relevance; leading to a somewhat uneven quality in source and replication. Of the most interest are Jackson’s always stunning pen and ink illustrations which are scattered throughout, including the colourised image of a winged Chnoubis on the cover. Featured most consistently is a selection of trumps from the Nigel Jackson Tarot, conveniently dotted throughout the book, usually in remarkably apropos locations. These are lovely, with Dame Venus as the Empress particularly evocative, but the replication quality is unfortunately inconsistent, with crisp and clear trumps sitting alongside soft or muddied ones.

As with all such titles published by Capall Bann, and as is always gleefully mentioned in these here reviews, there’s an appalling lack of proofing throughout this book, with an abundance of spelling mistakes, errant words and other typographic artefacts. Competing for the prize of best in show is the claim that there are about 10,000 Nestorian Christians were “incarnated” in Syrian refugee camps, putting a whole eschatological twist on religious persecution, displacement and incarceration.

Published by Capall Bann