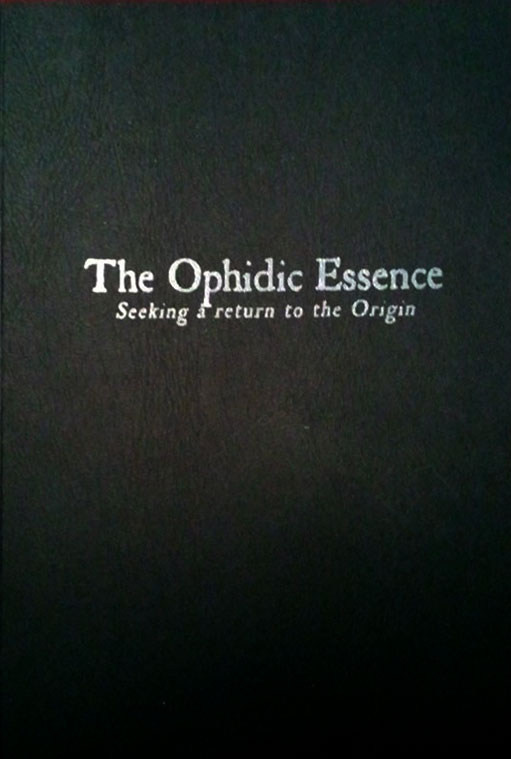

Published by Spiritual Outlaw, Samlag: The Path of Þursian Sexual Sorcery is one of two Þursian titles by Ljóssál Loðursson released in close proximity, with the other being his Ginnrúnbók, which was published through Spain’s Fall of Man press. Significantly shorter than that work, Samlag is a more focussed companion volume, considering, as its title tells it, the use of Þursian sex magic, with a particular focus on the erotic relationship between Loki and Angrboða. The brevity of Samlag is a feature of its chapters too, with almost all twelve being relatively succinct, abetted by the body type’s large point, with there being little fat on these bones as Loðursson introduces topics broadly and deftly moves forward.

Published by Spiritual Outlaw, Samlag: The Path of Þursian Sexual Sorcery is one of two Þursian titles by Ljóssál Loðursson released in close proximity, with the other being his Ginnrúnbók, which was published through Spain’s Fall of Man press. Significantly shorter than that work, Samlag is a more focussed companion volume, considering, as its title tells it, the use of Þursian sex magic, with a particular focus on the erotic relationship between Loki and Angrboða. The brevity of Samlag is a feature of its chapters too, with almost all twelve being relatively succinct, abetted by the body type’s large point, with there being little fat on these bones as Loðursson introduces topics broadly and deftly moves forward.

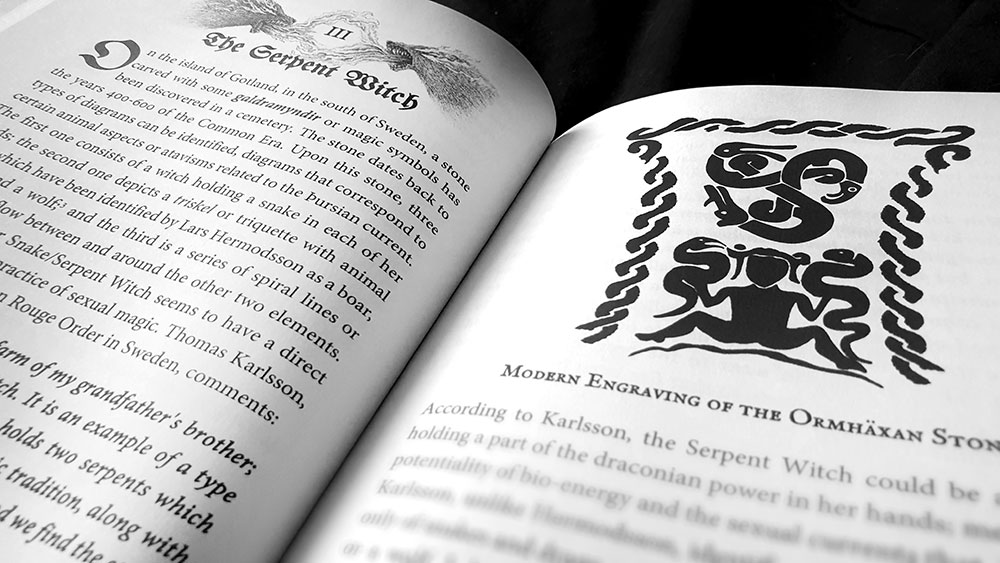

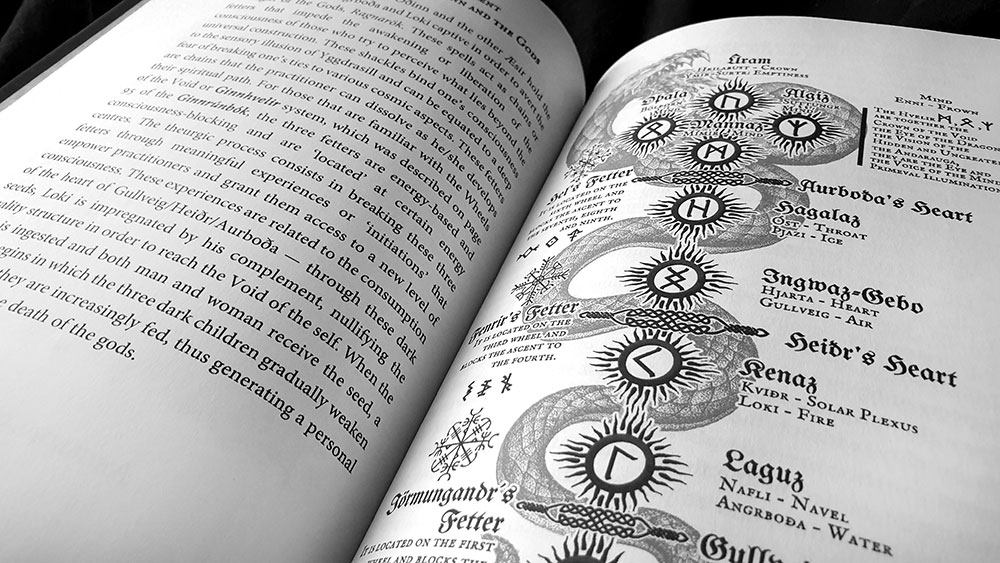

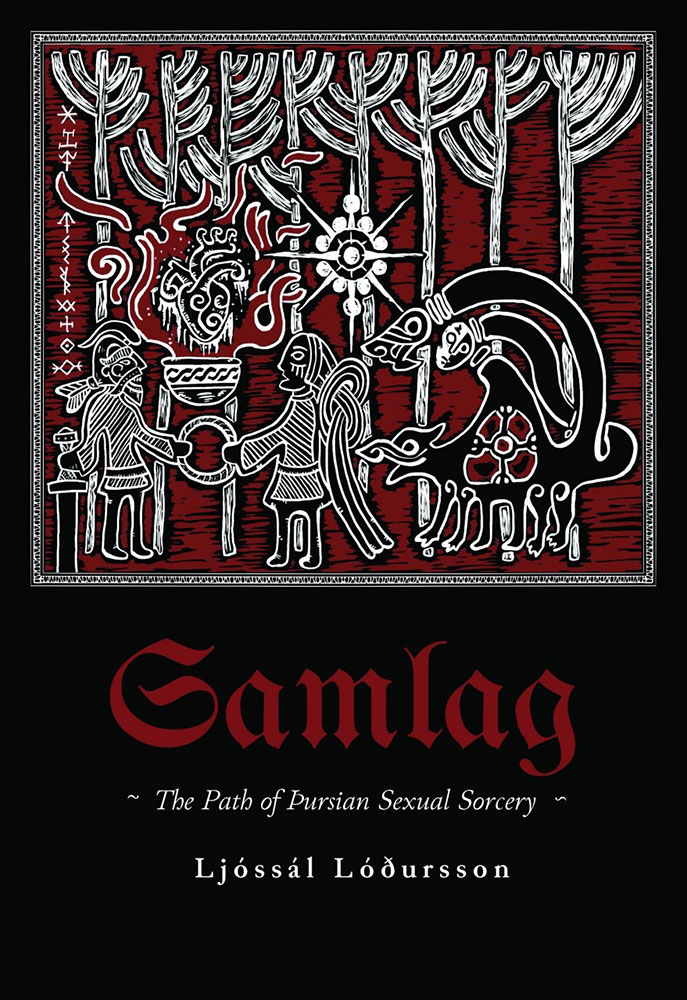

Samlag appears to start slowly at first, with somewhat disparate considerations of the Smisstenen or Ormhäxan stone from Gotland, and a thorough survey of examples of cardiophagy and other forms of flesh-eating from the eddas and sagas. But these are all individual strands that are then woven into the greater whole as the book progresses. The snake-wielding female figure on the Ormhäxan stone is interpreted as Angrboða or Hyrrokkin, with the three-headed triskelion above as her three children (Hela, Fenrir and the World Serpent), while the theme of cardiophagy relates to Loki’s eating of Angrboða-Gullveig’s heart, an act similarly associated with the birth of the couple’s three children. Indeed, Gullveig’s hugsteinn heart and other giant’s hearts, such as the hrungnishjarta, play a significant role within these pages, encapsulating many of the ideas of samlag like a sanguine arcanum.

Loðursson defines samlag as ‘communion’ and it is this exchange that is at the heart, if you will, of the three forms of sexual sorcery he presents here: Snýst Miðgarðsormr i Jötunmóð (a kundalini-like raising of serpentine energy), Náttúru Samlag (autoerotic summoning of spirits) and Loptr kvidugr af konu illri (a couple’s working described by Loðursson as a powerful antinomic and counter-cosmic sexual High Magic connected with the giants). Naturally, it is the Loptr kvidugr af konu illri working that is given the most attention here, with its procedure built around the words of its title: Loptr was impregnated by that evil woman. For those that hope that all this talk of impregnating Loki might involve some backdoor shenanigans, you’re going to be disappointed. Instead, what is presented here is a relatively straightforward Tantra-style configuration of Shiva and Shakti in which a male practitioner embodies Loki while their female counterpart does the same for Angrboða. It’s not quite such an absolute binary, though, as Loðursson defines both participants as effectively hermaphroditic, being simultaneously male and female in order to break illusionary laws of unity and dualism “through emptiness and polar holism.” The impregnation of Loptr, then, is an oral one in which menstrual blood is consumed in a version of Tantra’s yoni puja, with the blood of the female participant being analogous to the blood of Angrboða’s hugsteinn heart. This act is one that mirrors the creation of Hela, Fenrir and the World Serpent, and so has a similar effect, leading to the creation of a totem-housed egregore that incorporates elements of all three beings.

There are two other samlag workings either included or mentioned in this book. The first is an autoerotic one focusing solely on the woman embodying Angrboða, who in an act of “contra-cosmic autogenesis” creates two totems representing Hati and Sköll thereby re-enacting the line from Völuspá in which Angrboða as in aldna (‘the old one’) bears the brood of her son, Fenrir. The second working, with which Samlag concludes in a brief chapter, is only hinted at, and refers to the matrix of Loki, Sinmara and by extension, the mara or nightmare. Loðursson suggests that Loki is the grandchild of Surtr and Sinmara, and thereby posits an equine connection between grandson and grandmother via Loki’s transformation into the horse that lured away Svaðilfari and Sinmara’s association with the mara.

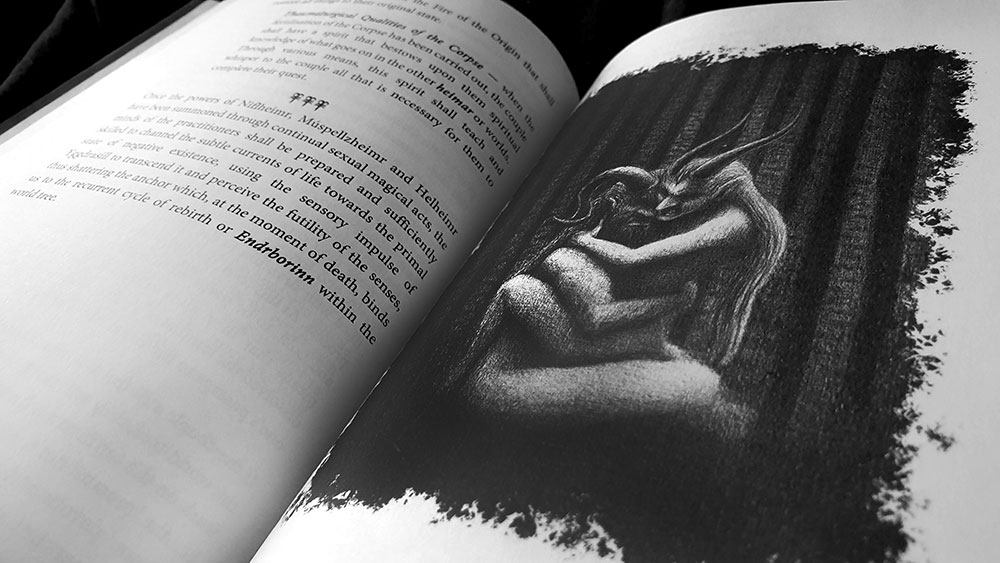

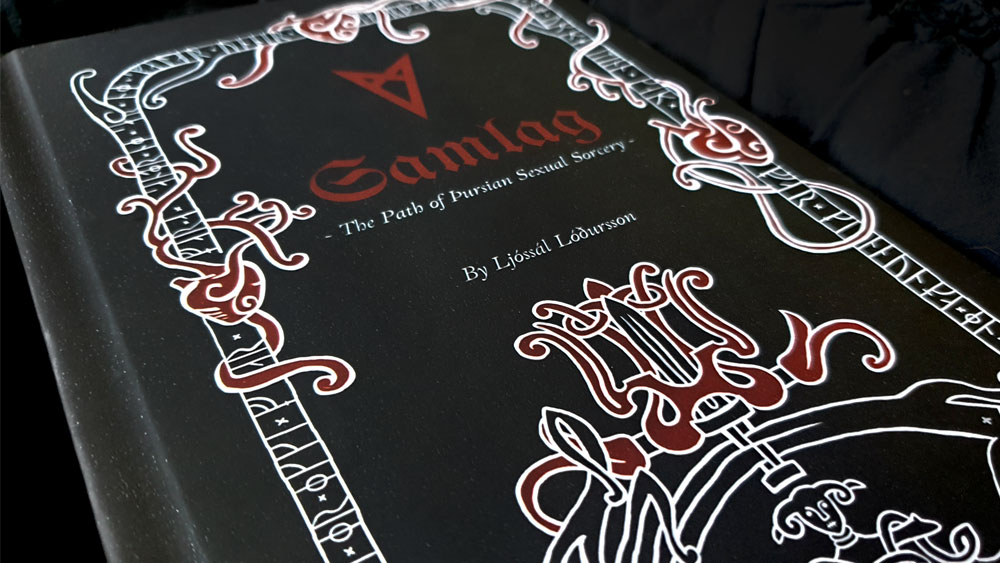

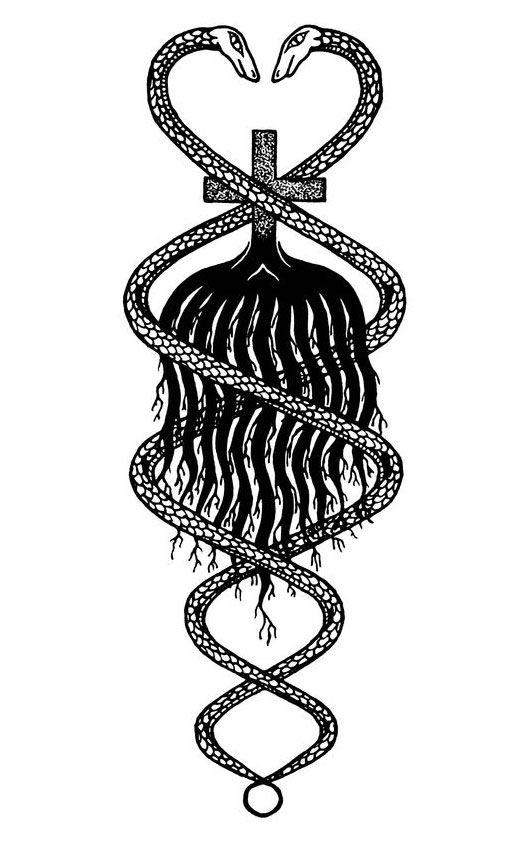

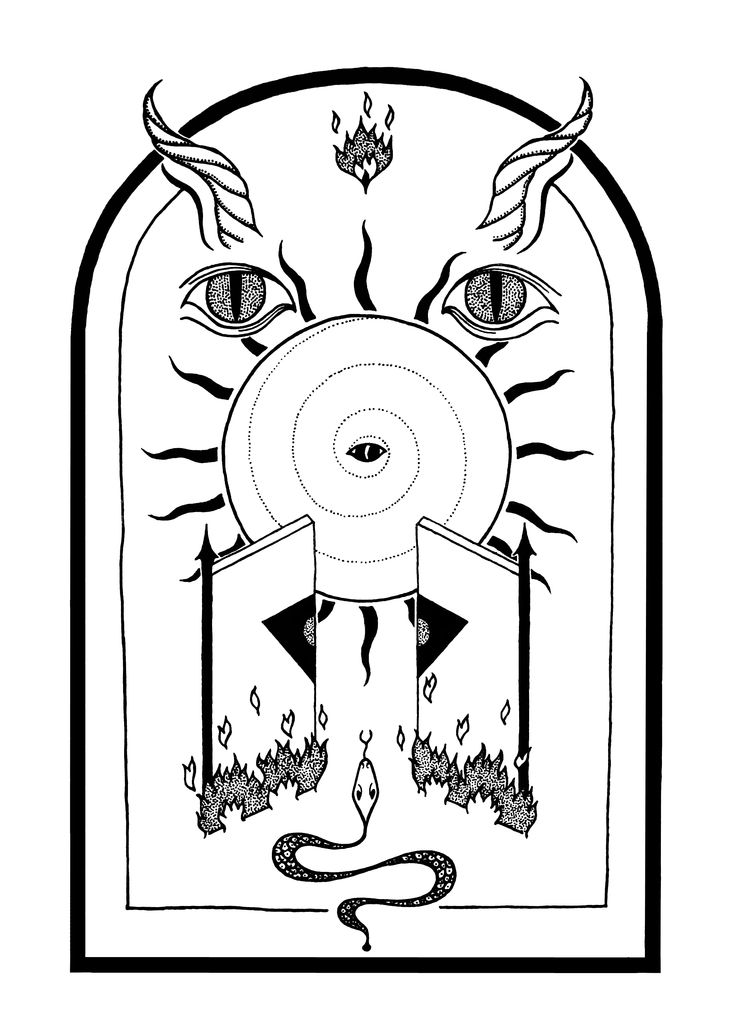

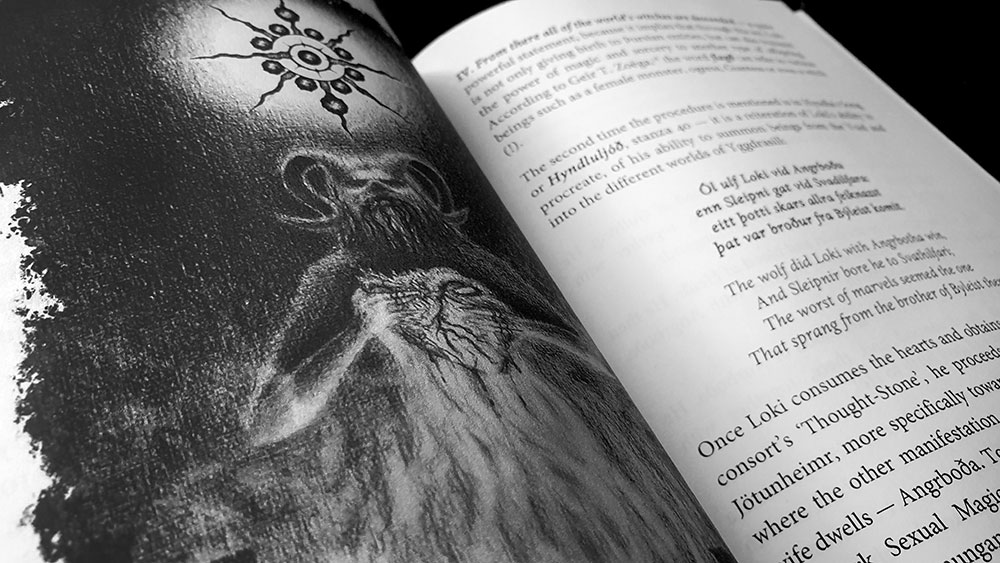

One of the pure highlights of Samlag is an aesthetic one, with the text ably accompanied by works from three different artists, Santiago David Gutiérrez, Diego Sanchez and Chris Undirheimar. It is Gutiérrez who makes the most immediate impact with a woodcut (or woodcut-style) image on the dustjacket depicting Loki and Angrboða around a burning heart, accompanied by Hela, Fenrir and the World Serpent, with the three siblings combined into one phantasmagorical chimera. With its stark shapes and restricted palette of red, black and white, Gutiérrez’s style is both distinctive and evocative, with a look that points to historical antecedents but has an atmosphere and consistency all of its own. The family portrait on the dustjacket also hides an entirely separate image by Gutiérrez on the hardcover itself, which makes for a lovely surprise with its intertwining rune border festooned with hearts, set in white and red against a black background. Elsewhere, Gutiérrez’s approach is contrasted strongly with that of Sanchez who has a more, how you say, metal hand, with densely rendered, full-page pencil images, principally of a horned and hirsute Loki.

The family portrait on the dustjacket also hides an entirely separate image by Gutiérrez on the hardcover itself, which makes for a lovely surprise with its intertwining rune border festooned with hearts, set in white and red against a black background. Elsewhere, Gutiérrez’s approach is contrasted strongly with that of Sanchez who has a more, how you say, metal hand, with densely rendered, full-page pencil images, principally of a horned and hirsute Loki.

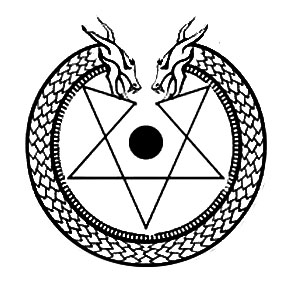

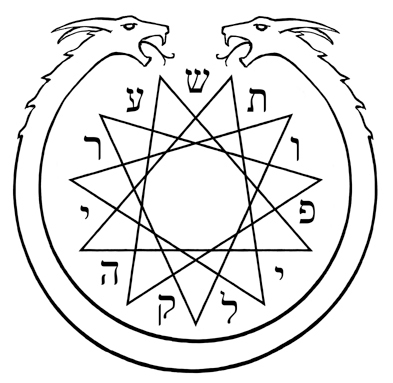

Samlag runs to just over a hundred pages and although it has been printed by print-on-demand company Lightning Source, it is bound as a rather fetching matte black hardback that is illustrated front and back, nicely wrapped in the aforementioned dustjacket. Body text is set in a large serif face, subtitles in a distressed antique serif, while titles are in a striking blackletter that is combined with a header illustration of twin wolves.

Published by Spiritual Outlaw