Originally published in 1920 and presented here in a 2004 translation from Rûna Raven Press, The Edda as Key to the Coming Age by Peryt Shou is something of a classic of early 20th century German rune magic. As Flower’s notes in his introduction, Shou’s book provides context to some of his own work as presented in Rune Might: Secret Practices of the German Rune Magicians published by Llewellyn in 1989. In this, he provided a survey of the various strains of last century German runo-mysticism, including that of Shou as well as the contributions of Guido von List, Friedrich Marby, and of course Karl Maria Wiligut. In Rune Might, the influence of Shou on Flowers was clear, and the publication of this source text puts flesh on those bones.

Originally published in 1920 and presented here in a 2004 translation from Rûna Raven Press, The Edda as Key to the Coming Age by Peryt Shou is something of a classic of early 20th century German rune magic. As Flower’s notes in his introduction, Shou’s book provides context to some of his own work as presented in Rune Might: Secret Practices of the German Rune Magicians published by Llewellyn in 1989. In this, he provided a survey of the various strains of last century German runo-mysticism, including that of Shou as well as the contributions of Guido von List, Friedrich Marby, and of course Karl Maria Wiligut. In Rune Might, the influence of Shou on Flowers was clear, and the publication of this source text puts flesh on those bones.

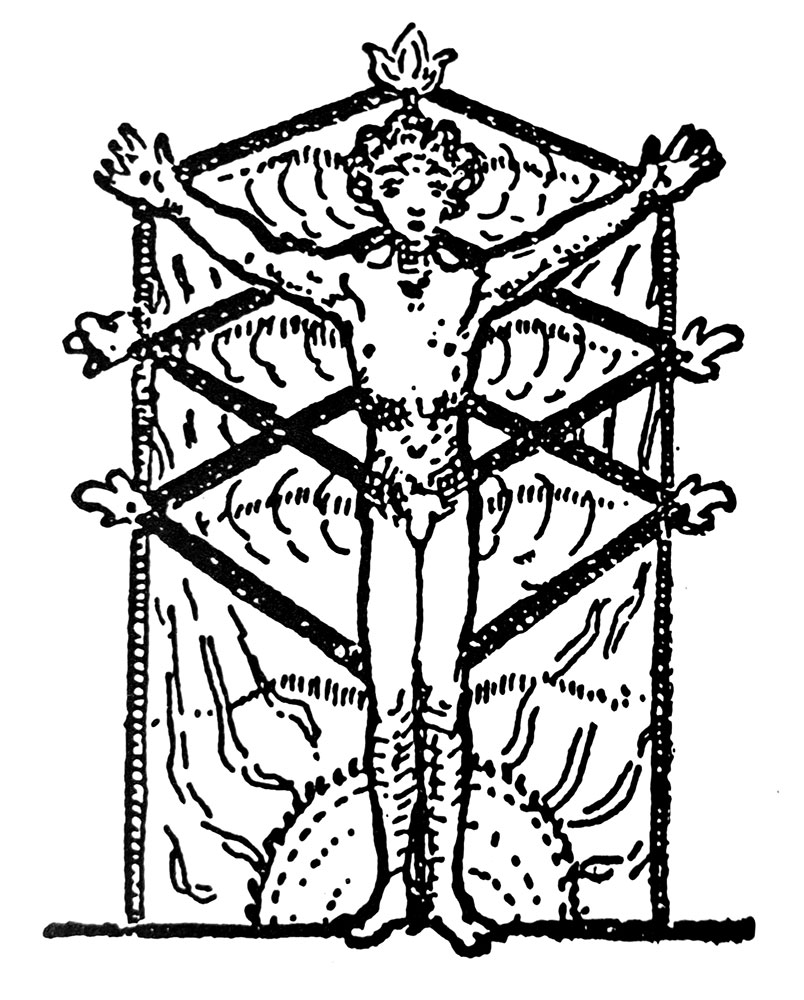

Shou’s cosmology as presented here represents a syncretism of rune mysticism with esoteric Christianity, seeing the cosmic Christ as an analogue of Wuotan, who he describes as the prehistoric Christ of the German folk. Shou is certainly not unique in this concept, as evidenced by far older precedents like the runestone from Jelling, Denmark, in which Christ appears not crucified but hung, entwined with foliage on a tree, in an echo of Odin’s hanging from the World Tree. Indeed, Shou takes this idea of a Germanification of Christianity as mythically central to his system, describing a stark break between the Christianity of Roman Catholicism and a vigorous Germanic Christianity; a break that occurred at the very point of the crucifixion. For him, Christ’s death marked the end of Catholic Christianity as a valid system, at which point Germanic Christianity began and Christ awoke on the World Tree, descending alive as Wuotan.

Central to this cosmology is the idea of Need, which seems to occupy positions both negative, comparable to desire in Buddhism and therefore the cause of suffering, and positive, as a force of will that provides the operations and indeed the whole system, with its impetus and energy. This concept of Need naturally relates to the rune Nauthiz, but Shou takes this further, seeing it encoded within the ‘N’ in the INRI acronym placed above the crucified Christ, and therefore a key to understanding that moment where Christ proper transformed into Christ-Wuotan. Shou associates this moment with Odin’s hanging on the World Tree as recorded in Hávamál, drawing attention to the idea that on the ninth night, screaming, he grasped the runes with Need.

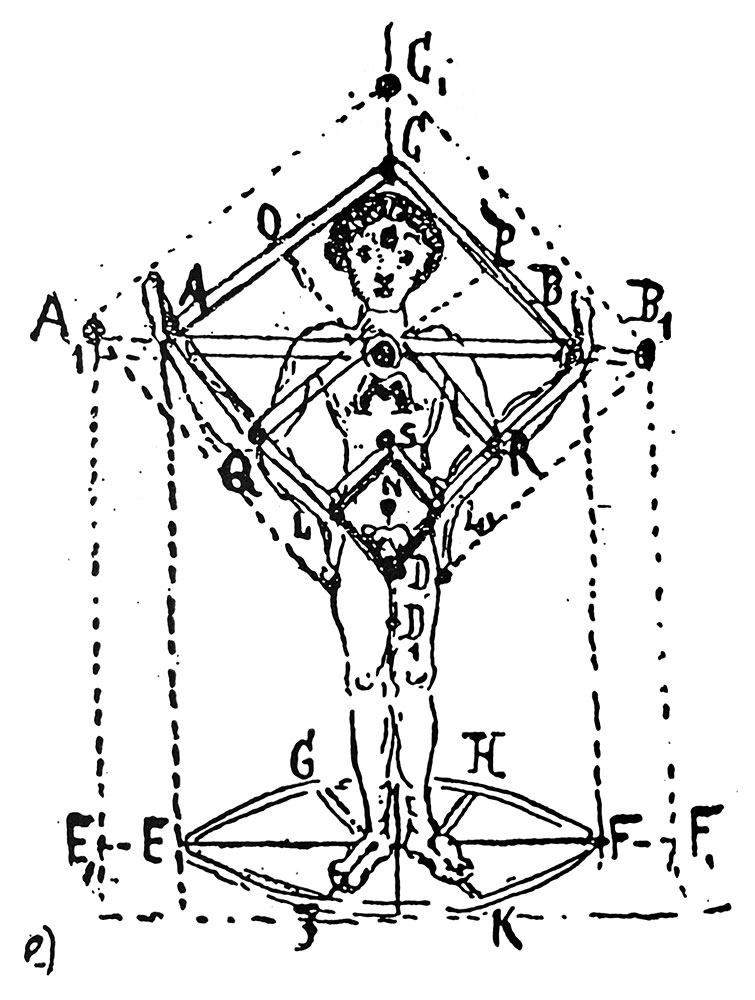

This intersection between the crucifixion of Christ and the hanging of Odin forms the basis of the main ritual Shou presents in this work, the Ritual of the Ninth Night. This ritual is a combination of special postures, visualisations and voice work that is redolent of the rune vibration and runic yoga of Shou’s contemporaries, and the core principles will be fairly familiar to anyone that has encountered occultism within the last century. In a series of procedures over several days or weeks, depending on one’s sense of progress, the practitioner gradually builds connections with cosmic energies, building an aethyric form that replicates the body of Christ-Wuotan. As the Tabernaculum Hermetis, this Adam Kadmon-like figure contains within it all the runes as vibratory symbols.

The nomenclature Shou uses to describe his system has an endearing retro-futurist technological quality to it, making it, in retrospect, feel slightly cyberpunk or evocative of the technomages of Babylon Five. In the Ninth Night ritual, the practitioner imagines themselves as a cosmic antenna, drawing on radio waves from the divine, and even entreating these forces to awaken the network within; drawing an explicit analogy between this mystical proto-internet and the instruction made by Jesus to his disciples to cast their nets. In concert with this surprisingly contemporary terminology is a lexicon that feels much more of its Theosophy-inspired time, filled with ideas of planetary energies and ascended masters, such as the Hermes-Brotherhood who appear to literally live on the planet Mercury. In a particularly intriguing moment, Shou refers to another priesthood on Mercury called the Wolves of the Sun who are hostile to Wuotan, and who obviously provide the template for the idea of the predatory wolves Fenrir, Hati and Skoll. Combined, these two strains of language and paradigms make for an appealing modality, a little old fashioned, a little futuristic, a little pagan and a little Christian.

One of the most interesting aspects of reading The Edda as Key to the Coming Age is considering its status as a historical and prophetic document, aided and abetted by the hindsight of nearly 100 years. With the book being written in the aftermath of the First World War and long before the rise of National Socialism (although part of the nationalist rebirth, and its sometimes problematic racism, from which it would draw), it is hard not to identify that most tumultuous period two decades then hence as the coming age Shou speaks of. This is certainly true when he says that the Germanic people are destined for destruction, something he ties to what he defines as an outdated definition of race, albeit to be reborn for the greater global good. Alternatively, it must be asked, is this still an age that is yet to come.

The Edda as Key to the Coming Age is a slim volume at only 57 pages. Shou, as translated by Flowers, writes with enthusiasm but also with the unchecked anthropology of yesteryear, where the etymology is often wishful and there’s very little citing of academic sources with an often inescapable feeling that some things could be several steps removed from the original material. There’s also a certain degree of repetition, despite the low page count, with the basic premise of Christ-Odin/crucified-hung repeated in several variations as Shou attempts to make his point in a largely poetic way. As an archival document, this is an important resource, and despite the repetition, a genuine joy to read; something abetted by that little bit of crazy that are the cosmic, early 20th century occultism elements.

Published by Rûna Raven Press and since reprinted by Lodestar.

Review Soundtrack: Peryt Shou by Inade and Turbund Sturmwerk.