Bearing the impressively arcane subtitle “Spectral Resonance and the Numen of the Gallows,” Richard Gavin’s The Moribund Portal is a meditation on the symbolism of the gallows, and its place in folklore, spiritism and occult philosophy. From the opening paragraph, The Moribund Portal reads like what you would expect from a Three Hands Press title, and certainly moreso than another recent release. This involves, if we dare coin the phrase, a Schulkian type of sentence structure, gloriously beginning the proceedings with “Sites of archaic tragedy, iniquity, or turmoil can server the living as stations of unique spirit function.” Yes, indeed.

Bearing the impressively arcane subtitle “Spectral Resonance and the Numen of the Gallows,” Richard Gavin’s The Moribund Portal is a meditation on the symbolism of the gallows, and its place in folklore, spiritism and occult philosophy. From the opening paragraph, The Moribund Portal reads like what you would expect from a Three Hands Press title, and certainly moreso than another recent release. This involves, if we dare coin the phrase, a Schulkian type of sentence structure, gloriously beginning the proceedings with “Sites of archaic tragedy, iniquity, or turmoil can server the living as stations of unique spirit function.” Yes, indeed.

Running to just 90 or so pages and undivided by chapters, save for a clearly defined epilogue, or even subheadings, The Moribund Portal feels more like an extended essay than a true book. It is, indeed, what the title says, a portal that is formed by the image of the gallows, but which uses this morbid focus as a means of moribund egress to explore a variety of related themes. Untethered by the structure and clear signposts provided by subheadings, there’s a feeling of the thematic focus swinging, like a gibbet hanging from a gallows tree, as topics move from one to the other. Thus, the occupant of the gallows proves an apt leaping off point, if you’ll pardon the allusion, leading to discussions of the hand of glory, mandrake, dreams, while touching variously on Cain, Germanic mysticism, tantra, and perhaps most intriguingly, given its uniqueness, Canadian folklore. Gavin uses two examples from the latter as rather significant talking points: a tale of an enigmatic hanging from York (now Toronto) and the Québécois folk legend of la Corriveau.

Despite its length, The Moribund Portal is not necessarily a brisk read, due to Gavin’s style of writing. He writes with a considered, grandiloquent and formal delivery, but does so expertly, without falling into the traps that lesser authors do when ambition outstrips ability. Instead, Gavin’s presents a masterclass in how to write 21st century occult style, combining academic phrasing, sophisticated occult terminology (your ‘numens’ and ‘sodalities’ but alas, no ‘praxis’) and just the right sprinklings of archaism. Never overdoing any of these elements, and thereby disappearing into black holes of meaningless, it’s all tied together with perfect punctuation. Writing in such a deliberate way is often, I find, its own form of proofing, as the careful concatenation of words requires constant revision. For this reason, or not, there’s little to complain about here with spelling and punctuation, especially compared to other recently reviewed titles; with only one noticeable spelling mistake really jumping out. The result is a read that feels sophisticated and knowledgeable, rather than someone trying their damnedest to sound erudite or attempting to use a lexicon not naturally their own (you know, most occult authors).

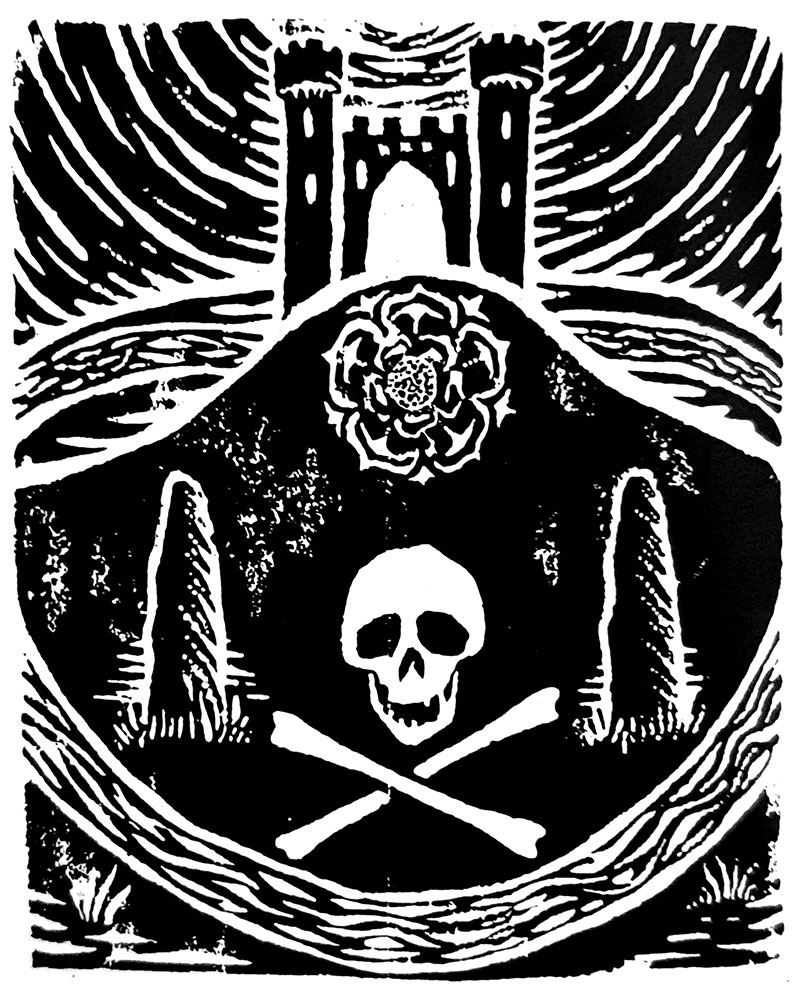

The Moribund Portal features a stunning image by Benjamin A. Vierling as the cover, while the typesetting is by Joseph Uccello, both Three Hands Press stalwarts. Like the portal of the title which is reflected in the framing design on the cover, The Moribund Portal is an atypical 9.5 x 6 x 1.5 inches, with its narrow dimensions making it fit easily in one hand when closed. This smaller width does make the binding a little tight, especially given its sub-100 page length, so it’s one of those volume where a little more effort than usual is needed to turn the pages and hold them open, leading to fatigue and the occasional shaking of hands to dissipate the ache.

Three Hands Press have released The Moribund Portal in three editions: as a softcover trade paperback limited to 1,700 copies; a limited hardcover bound in gilt tyrian purple, of 500 hand-numbered copies; and as a deluxe hardcover edition of 22 hand-numbered copies in full purple Nigerian goat with marbled endpapers and slipcase

Published by Three Hands Press.