A quick survey of Scriptus Recensera’s hallowed halls shows that Saturn has a certain degree of popularity within this here occult milieu, with our shelves bearing several books both by, and about, the Fraternitas Saturni, along with two Saturnian titles from Aeon Sophia Press, Moshe Idel’s Saturn’s Jews: On the Witches’ Sabbat and Sabbateanism and now this volume from Theion Publishing. In some ways, The Cult of the Black Cube takes things back to basics with a general overview of matters Saturnine, with an overview of various incarnations of what Dr. Arthur Moros broadly refers to as the Saturnine deity, followed by theory and a little practicum.

A quick survey of Scriptus Recensera’s hallowed halls shows that Saturn has a certain degree of popularity within this here occult milieu, with our shelves bearing several books both by, and about, the Fraternitas Saturni, along with two Saturnian titles from Aeon Sophia Press, Moshe Idel’s Saturn’s Jews: On the Witches’ Sabbat and Sabbateanism and now this volume from Theion Publishing. In some ways, The Cult of the Black Cube takes things back to basics with a general overview of matters Saturnine, with an overview of various incarnations of what Dr. Arthur Moros broadly refers to as the Saturnine deity, followed by theory and a little practicum.

But first, after an introduction from Frater U.:.D.:., Moros begins with a personal anecdote, giving his life story, from being crippled and having his spine damaged in high school, to nascent explorations of academia, to a dramatic Roman-style necromantic invocation, and finally a dream encounter with a black creature of pulsing energy that led to a miraculous curing of all ills and the beginning of a journey along the path this book reveals. Given that the name of the good doctor is a pseudonym, and the biography is without significant markers of time or space (save for a reference to an unspecified Ivy League school), this account feels like it is caught in a slip of myth. This is then compounded with Theion Publishing reporting that Moros died soon after delivering this manuscript to them, his body found exotically “in the land of Kush” where he, like some Lovecraftian or Rider Haggard hero, “never afraid of adventure and risk, investigated ancient traces of the Saturnian Cultus. Contact had been lost for days until his body was found. The cause of death remains unknown.” Thrilling Boy’s Own stuff.

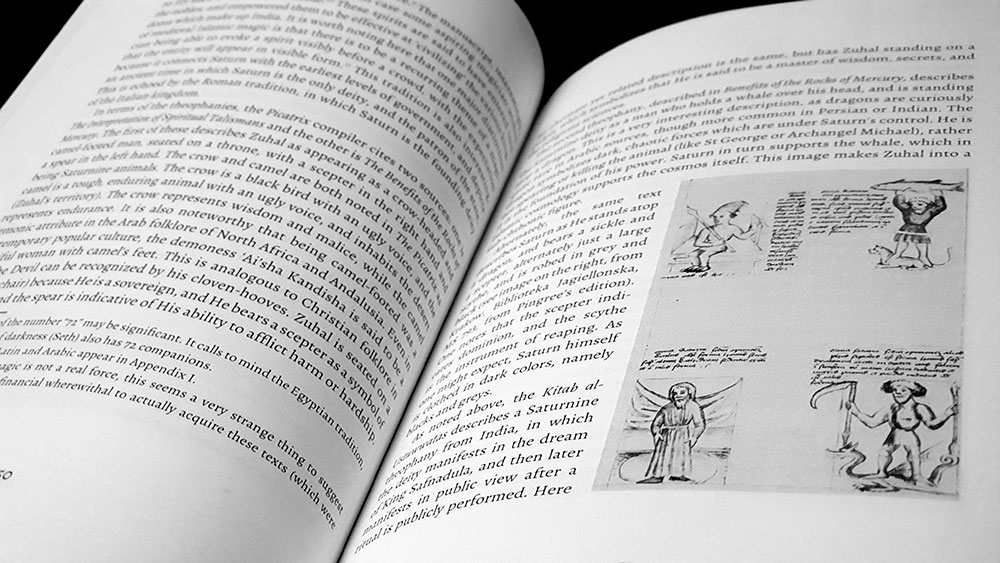

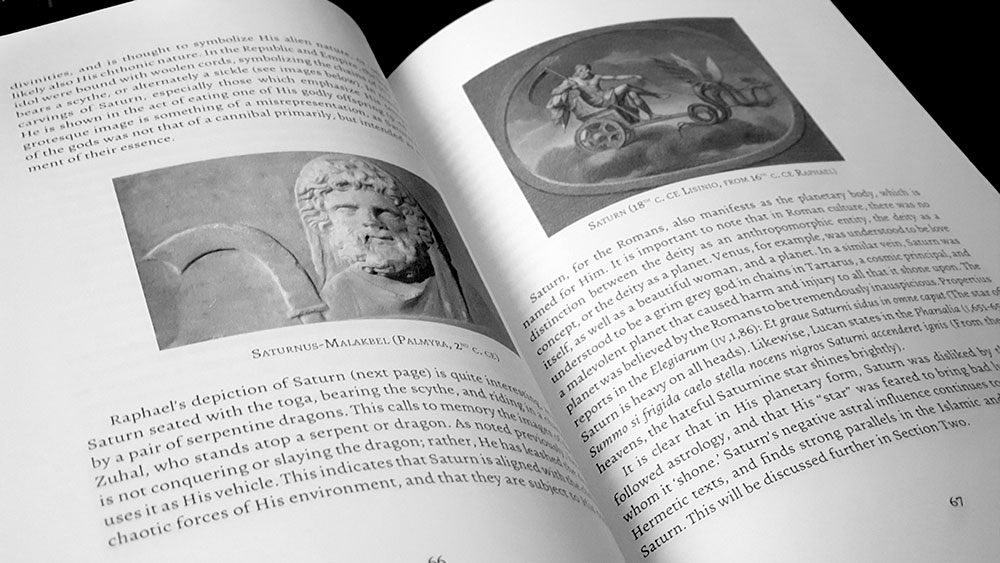

Moros begins his consideration of the various iterations of the Saturnine deity not, as one might expect, in ancient Greece, but in the later world of Medieval Islam, where the form is that of the spirit Zuhal; perhaps familiar as the planetary spirit Zazel from grimoires like Clavicula Salomonis; or an award-winning American erotic film from 1996, apparently – the more you know. For his depiction of Zuhal, Moros draws largely from the third to fourth century text Nabatean Agriculture (Kitab al-falaha al-nabatiya), credited to a writer named Qûtâmä, and translated into Arabic at the beginning of the tenth century by the polymath Ibn Wahshiyya. It’s worth noting that, for whatever reason, Moros presents Wahshiyya as the text’s author throughout, never once giving credence to, or mentioning, his longstanding identification as only its translator. Zuhal shares many of the characteristics common to classical depictions of Saturn: death, decay, the persistence of time, and most importantly from an aesthetic perspective, a range of appealing stygian symbols: black stone, black sand, black man. The content of Nabatean Agriculture flows neatly into that of The Picatrix and considerably lesser known texts like Kitab al-Ustuwwatas, which provide still further details to the Arab world’s vision of the Saturnine deity.

Following a fairly thorough sojourn in the Greek and Latin climes of Cronos and Saturn, Moros takes an easterly turn and heads to India, which he identifies as the only place that the Saturnine cult has “survived since ancient times.” Here, ?ani shares many of the characteristics of his classical and Arab counterparts, something that likely developed alongside the other elements of Jyotisha or Hindu astrology in the centuries after the arrival of Greek astrology in India with Alexander the Great. He is slow like the passage of the planet, and associated with the colour black, the metal iron and suitably piceous animals such as crows.

With this anthropological exploration out of the way, Moros turns theoretical with the book’s second section, Saturnine Gnosis, which includes an analysis and interpretation of the Saturnine deity and an outline of what constitutes the Saturnine Path. Moros begins this with a broad discussion of spiritual paths, in which he throws shade at occult teachers who claim to be able to teach you how to become a deity whilst physically incarnate (a living god, if you will), yet are strangely unable to direct their own lives… *zing.* Dismissive of attempts to reframe spirits and gods as archetypes or aspects of the self, Moros argues that the consistent appearance of the Saturnine deity within a variety of cultures is because they are real, an “actual deity (or planetary intelligence, or power) with which various cultures have made contact.” As for the reason for pursuing the Saturnine Path, Moros lightly touches on the ebony elephant in the room that is asking why anyone would want to interact with such a malign and negative deity, highlighting the antinomian element behind this act, acknowledging that in siding with the exiled, wounded and marginalised, one is backing a dark horse, “but that dark horse is definitely in the race.” Initiation into this Saturnine current has, according to Moros, two main rewards: access to the gnosis that flows from the Saturnine deity, and the ability to draw on the power and emanations of Saturn’s Black Cube to work magic.

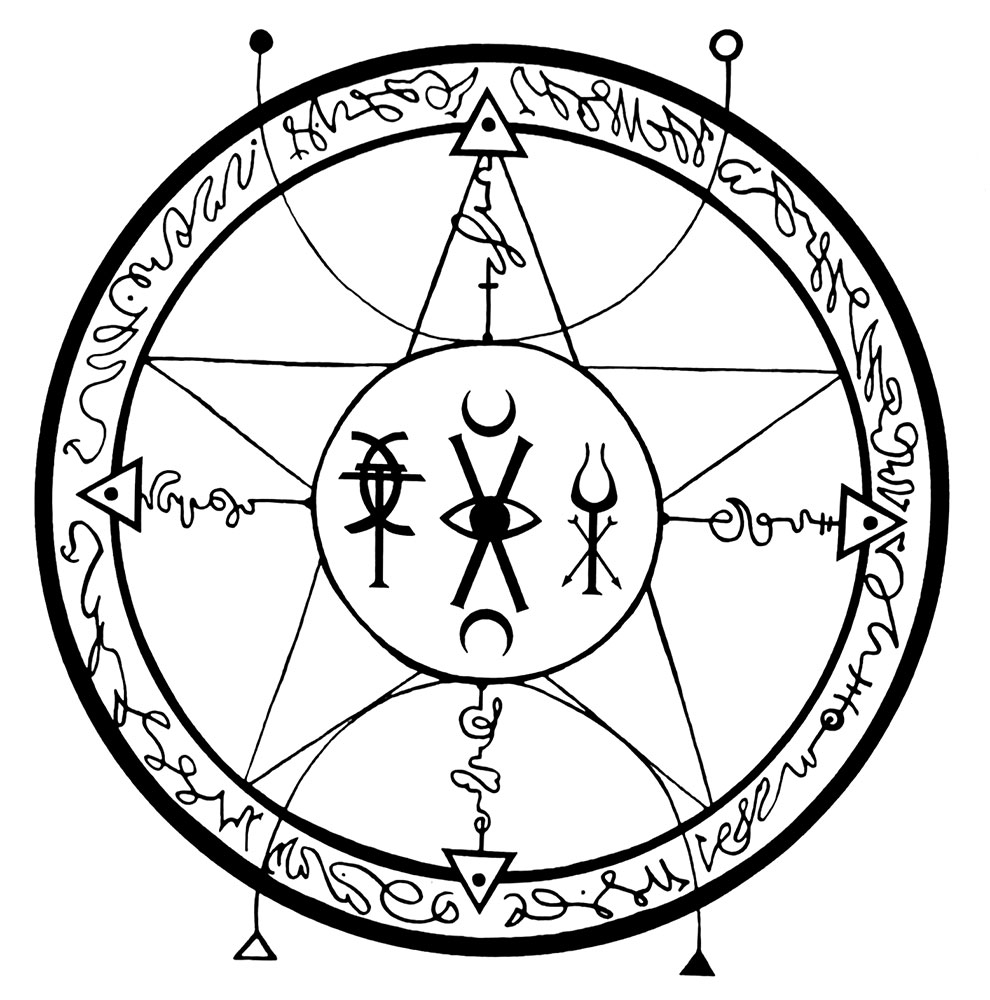

The practical side of this path is then laid out in the book’s third and final section, and follows some fairly familiar guidelines. The ritual space is what one would expect without even looking: it’s black, the ritual accoutrements include any of the symbols associated with the various iterations of the Saturnine deity, and the shrine is treated as a living thing that grows in power. Daily devotions play a role here, and the space, once established, should begin to aid the flow of Saturnian gnosis. Along with the devotional aspect, the example of ritual work includes a self-initiation, a rite for aide in oracular matters, rites using a black cube and chains respectively, and several rites to summon Saturn, based on the templates from The Picatrix and Nabatean Agriculture.

At 175 pages, The Cult of the Black Cube succeeds at what it is: a concise introduction to working with the Saturnine deity, providing enough mythology to give you a grounding in their character, and enough basic ritual elements to start devotional practice. Moros writes capably and confidently, free of error, and while there’s little in the way of in-text citing, it is clear where most information comes from, and these, both source texts and scholarly reflections, are referenced in an annotated bibliography at the rear.

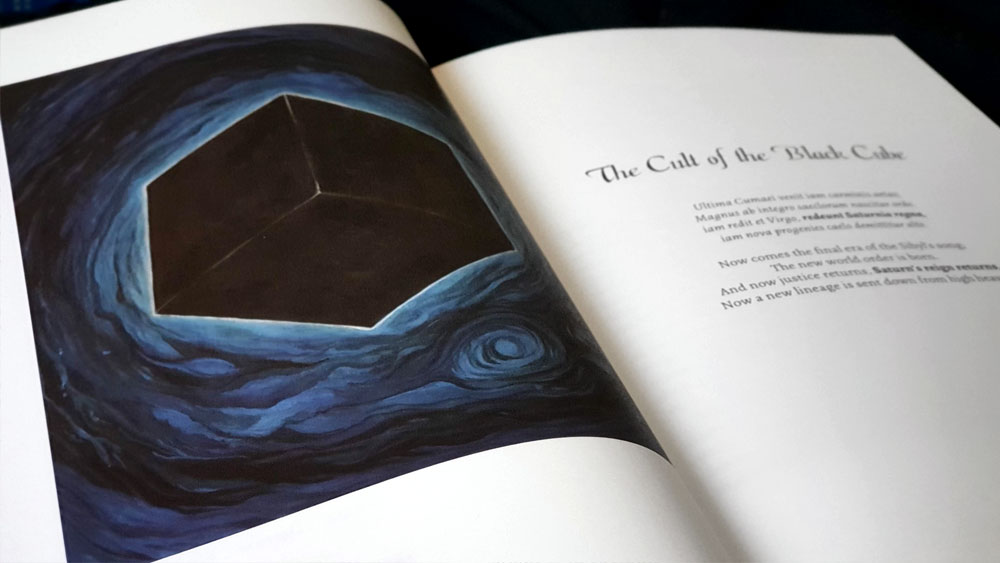

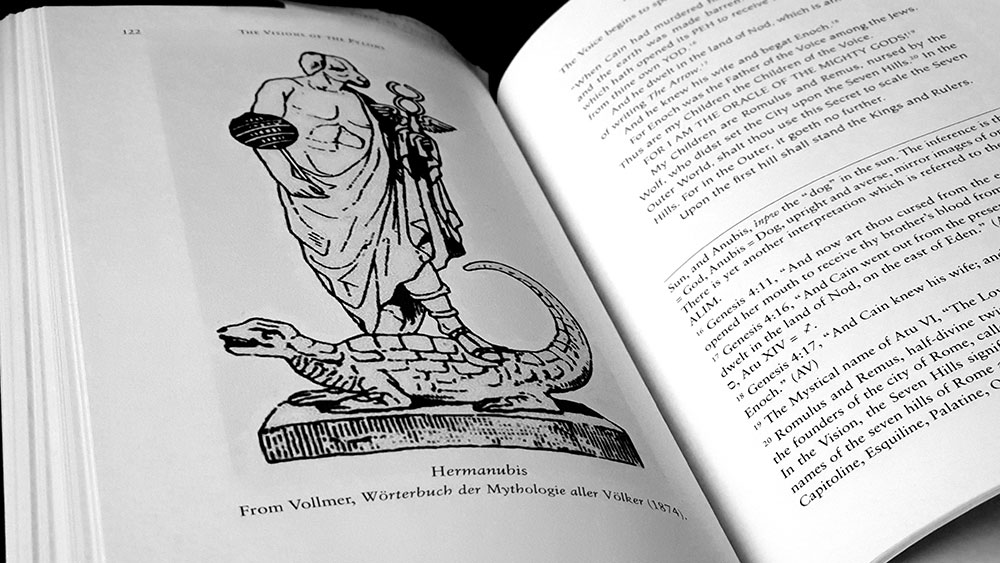

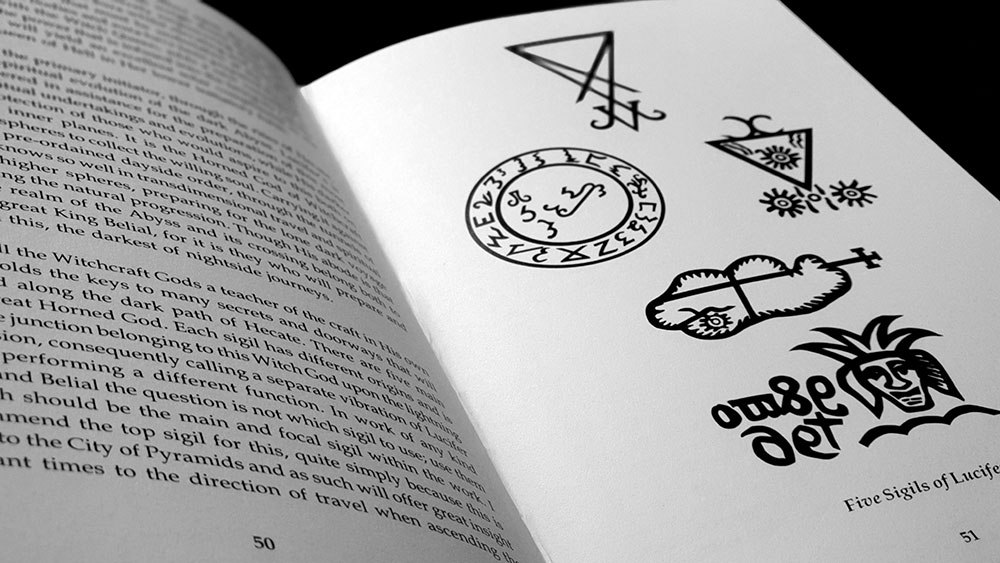

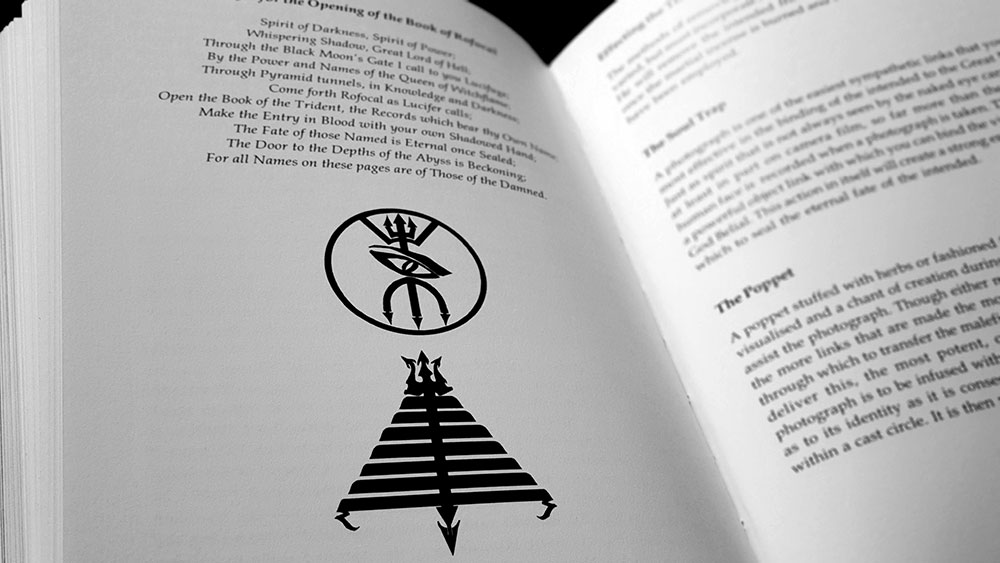

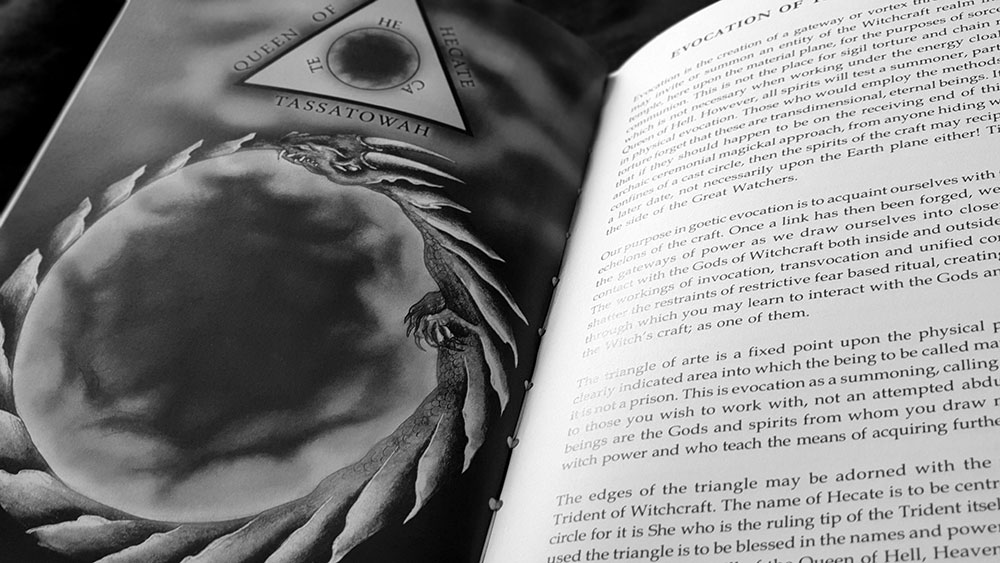

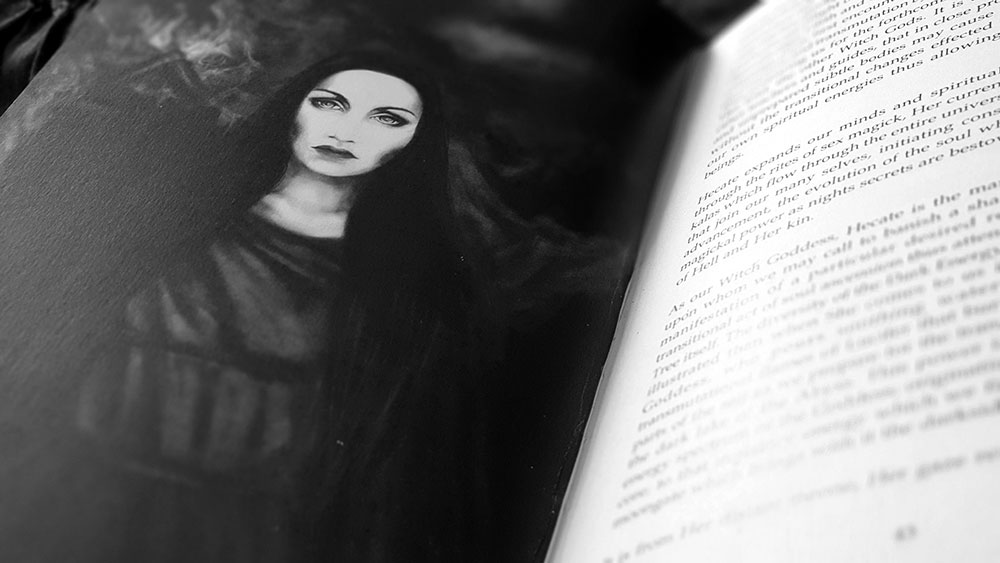

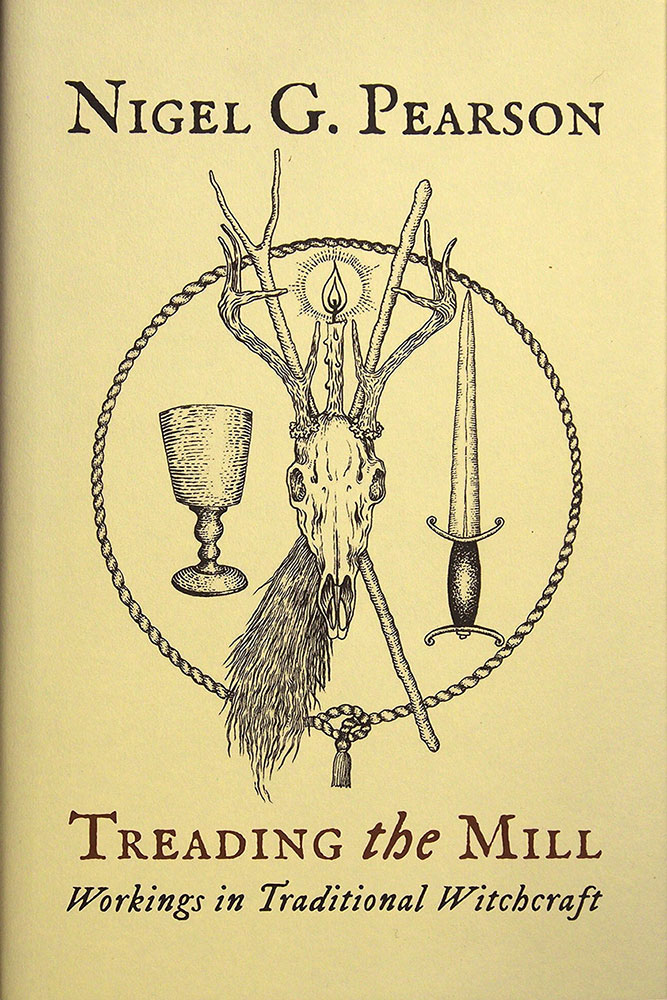

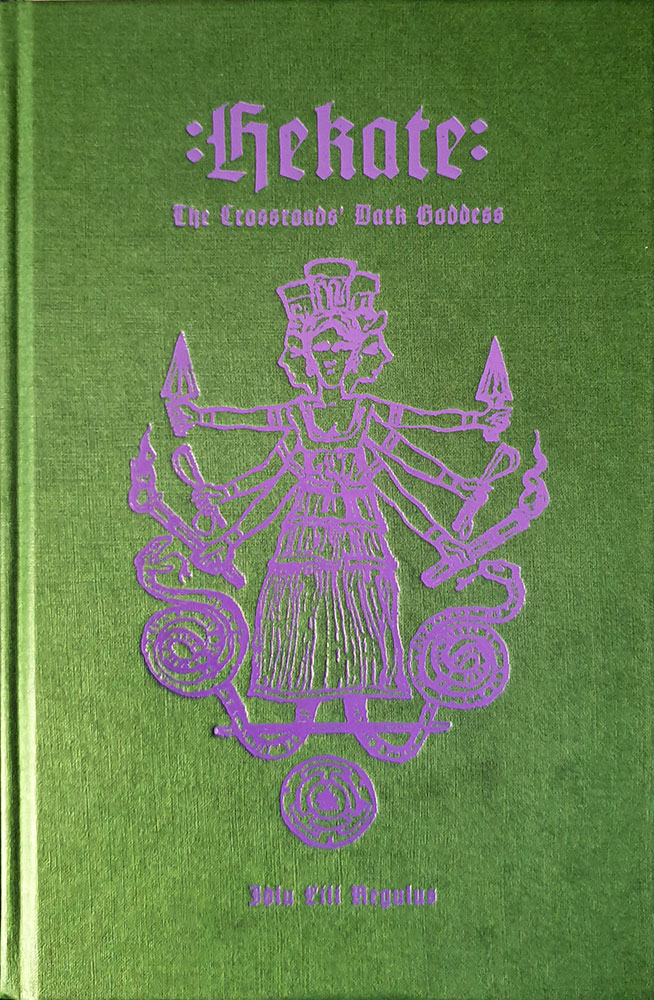

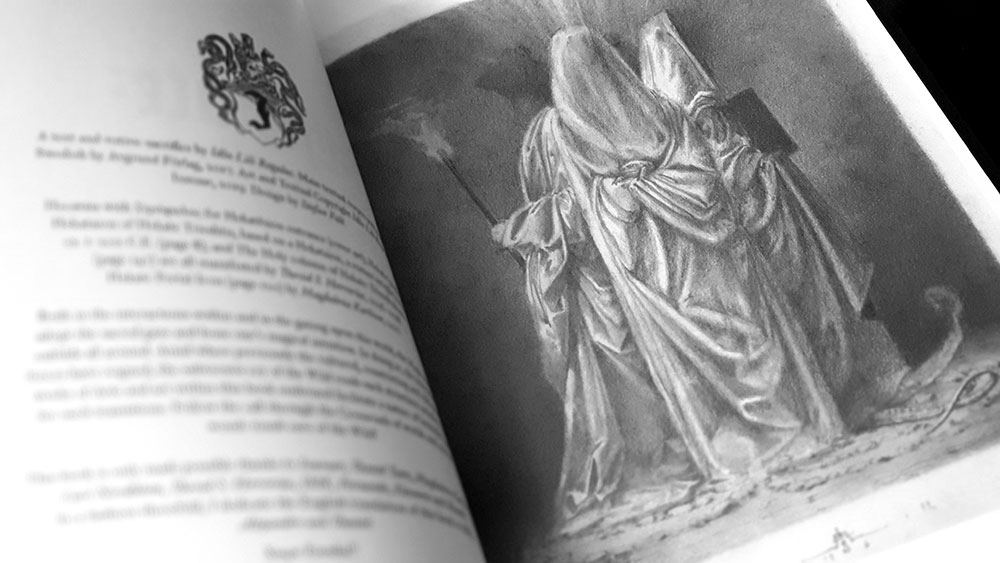

Layout and typesetting in The Cult of the Black Cube is by Jessica Grote in a functional style, with body text in paragraphs of a fully-justified serif, subtitles in Fredrick Nader’s Amerika face, and titles (and the whole contents page, for some reason) in Casady & Greene’s middling script face CalligraphyFLF. Illustrations are largely limited to in-body images depicting the various incarnations of the Saturnine deity, with the exception of an evocative full-page colour painting of the black cube by Erica Frevel that acts as something of a prelude to what follows.

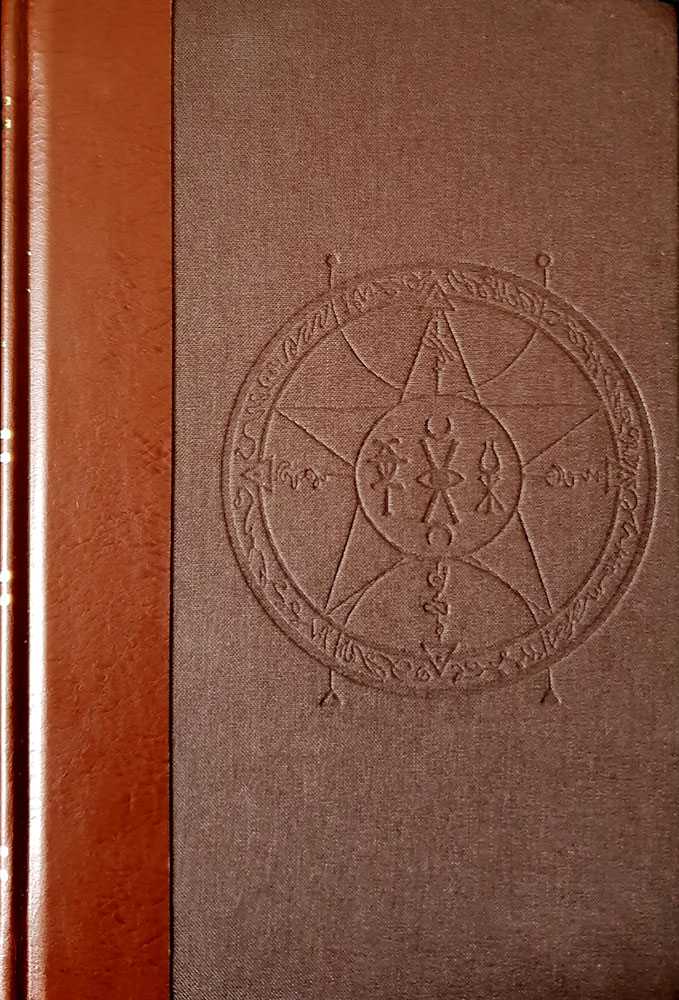

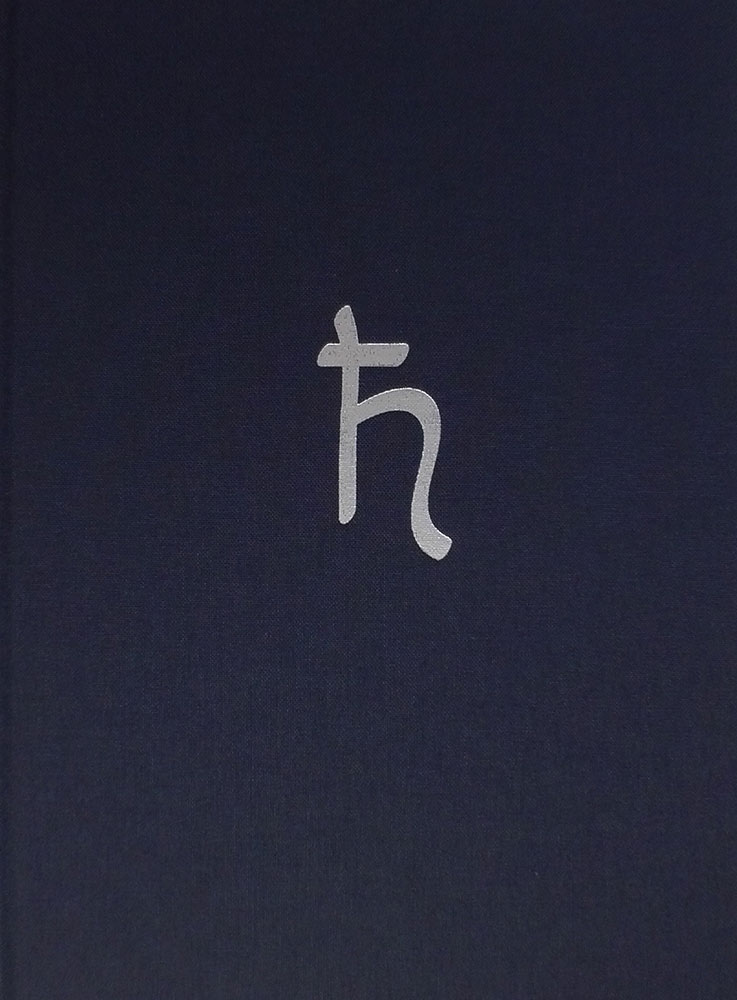

The Cult of the Black Cube comes in two editions, standard and auric, both printed on 115gsm wood-free high quality Lessebo Design paper, and several black and white illustrations throughout. The standard cloth hardcover edition is limited to 720 copies and is bound in blue-grey fine cloth, with a silver Saturn sigil debossed on the front, lettering in silver on the spine, and Surbalin moiré endpapers. The 52 hand-numbered copies of the sold out Auric Edition were fully hand-bound in Saturnine black leather, with a sigilised and embossed lead plate, individually consecrated to the deity, embedded on the front.

Published by Theion Publishing