Some of the first reviews featured on Scriptus Recensera predated the creation of this website and provided ready-made content when we first launched. Two of these were reviews of works by R.J. Stewart, reflecting a long-standing personal affection for his brand of earth, faery and underworld-focused mysticism. This title is another entry in what Stewart defines as his UnderWorld and Faery series, which also includes the two previously reviewed titles, The Underworld Initiation and The Living World of Faery, as well as the seminal works, Earth Light and its sequel Power Within the Land. While those titles all considered their themes in a broad manner, this one, as its title indicates, has what promises to be a particular focus on healing, presenting a variety of practical exercises for faery healing and the idea that in the modern era this can lead to a broader healing of the earth itself, mending the relationship between humanity and the planet.

Some of the first reviews featured on Scriptus Recensera predated the creation of this website and provided ready-made content when we first launched. Two of these were reviews of works by R.J. Stewart, reflecting a long-standing personal affection for his brand of earth, faery and underworld-focused mysticism. This title is another entry in what Stewart defines as his UnderWorld and Faery series, which also includes the two previously reviewed titles, The Underworld Initiation and The Living World of Faery, as well as the seminal works, Earth Light and its sequel Power Within the Land. While those titles all considered their themes in a broad manner, this one, as its title indicates, has what promises to be a particular focus on healing, presenting a variety of practical exercises for faery healing and the idea that in the modern era this can lead to a broader healing of the earth itself, mending the relationship between humanity and the planet.

Stewart further delineates this process into three steps, defining the faery healing of the first as a transformation through interaction with the faery as well as other orders of life, rather than conventional modern healing, be it, one assumes medicinal or metaphysical. The second stage marks a meditation, in alliance with these other orders of being, on the subtle forces of life and death, while the earth healing of the third and final stage is itself defined as three further stages: cleansing and healing ecological areas adversely affected by humanity; healing rifts and imbalances both metaphysical and literal in the underworld; and finally an iatrical interaction with the living consciousness of the earth itself, taking place at its very core, a locus of power from which what Stewart terms the Earth Light and the Shining Ones originate.

Out of the gate, the practical side of The Well of Light meets a snag, with Stewart explaining how to use the book, the first stage of which is to listen to the CD all the way through. OK, I’ll get right on it… oh, wait, what CD? As miffed reviews on Amazon attest, this CD of empowered visions accompanied by flute and 80 stringed psaltery did not come with the book and had to be purchased separately. Should you feel it necessary, both book and CD appear to still be available for purchase from Stewart’s own website some seventeen years later.

Foregoing the requirements of the compacted disc variety, the reader can dive into a few introductory essays that offer an overview of the nomenclature and entities of Stewart’s tradition. Written over a period of time to answer questions that arose in Stewart-led workshop, they provide a broad outline of some of the themes and practices considered in more depth later and begin by discussing several orders of beings: elementals, nature spirits, faeries, and deepest still, titans or giants. The consideration of the giants is, perhaps obviously, the most personally interesting here, with Stewart comparing Germanic, Classical and Celtic variations of the motif to sympathetically define these beings as primordial powers embodying the land and other natural forces, manifesting as energies of creation, growth and ultimately destruction. He provides several suggestions of ways for connecting with these titanic powers: using an altered perspective, meditating on the weather, visiting mountains in body or in spirit, and through the intercession of faery cousin and allies.

As a collection of separately written essays, some of this initial content can feel a little unfocused or hesitant, but still carries Stewart’s distinctive voice. He writes in a largely informal, conversational manner, occasionally dropping analogies and also, a little too often, making curmudgeonly jibes at various things in modernity that annoy him; take that, Sony Walkmans, and for an only slightly more current reference “trying to get our computers to download so-called time-saving free music.” I do love the mental image of Bob Stewart shaking his fist at a yellowing Compaq Presario going “Damn you Napster, why won’t you work?”

Once The Well of Light gets going, going it gets, with an initial deeper introduction to the faery races and inner contacts, as viewed from the perspective of what Stewart calls the Faery and UnderWorld tradition. The idiosyncratic formatting of UnderWorld is chosen to differentiate it from any ideas of organised crime that might be evoked by the term; not something that really occurred to me, but obviously of some concern to Stewart. Indeed, this concern with definitions is one that arises frequently, and Stewart is at pains to point out when something from his lexicon should not be seen in the way it might normally be. Faeries are the most obvious one here, with repeated insistences that they should not be viewed as they are in popular culture (or in, as Stewart scathingly notes, the “many superficial books currently on the market”) as whimsical and diaphanous.

With definitions out of the way, Stewart introduces the first experiential part of the books with the concept of the aptitudes, faery healing’s seven areas of expertise. These seven aptitudes are inherent abilities or potentials, albeit perhaps unrealised, that everyone has at least one or more of, allowing the person to heal by working with stones, water, plants, living creatures, faery allies, touch and signatures. Stewart provides ways of discovering one’s particular aptitude, as well as broad ways of working with them, usually offering general guidelines, rather than exercises to be performed by rote. More depth is provided in the following chapter, where Stewart gives specific techniques, but only for working with the stone and water aptitudes, the practices acting as general models, with the onus on the possessors of other aptitudes to apply in kind.

If one expects a book with a title such as this to have pages of information about dubious energy healing and laying on of hands, then disappointment ahoy. There’s very little of such specifics, and not much in the way of any explicit definition of what ‘healing’ might mean in this situation, be it physical, psychic or mental. Instead, the concept of healing seems almost secondary, a side effect of what is presented here, which more often than not is a primer of working with the faery in general. This is particularly evident in the sixth chapter, Forms and Visions of Faery Healing, which, despite the title, contains a series of guided visualisations for encounters with various locations and characters in faery land; rather than a visit to a faery doctor. Effectively, the idea seems to be one of diplomacy, where the ongoing interaction between the practitioner and the denizens of the underworld creates a healing of the wounds betwixt the two worlds and its races.

This book contains a second part called The Mystery of the Double Rose, which is somewhat confusingly and ambiguously referenced in the cover art, and seemingly distinct from the main Well of Light section, but obviously thematically related. Counterintuitively, this section contains a considerably more explicit explanation of what is meant by faery healing than is found in the first half of the book. Along with some repetition of some similar information from the book’s first half, this affirms the status of The Mystery of the Double Rose as separate content that could have been better integrated into a single book; much like the introductory essays.

In all, then, The Well of Light feels like a welcome but by no means required addition to Stewart’s oeuvre of underworld and faery, with his other books in this canon providing more focus and a more essential explication of its tradition and imagery. As always, the curmudgeonly side of Stewart’s writing can begin to grate after a while, especially with the way he imbues his objections with such passion and indignation; yeah, I’m looking at you, those who sexually mutilate flowers by cutting them.

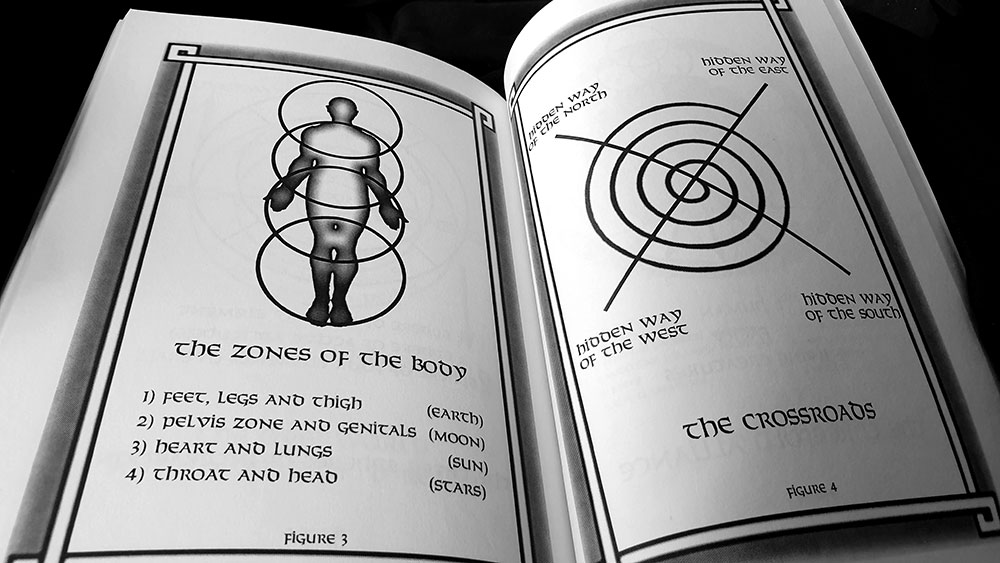

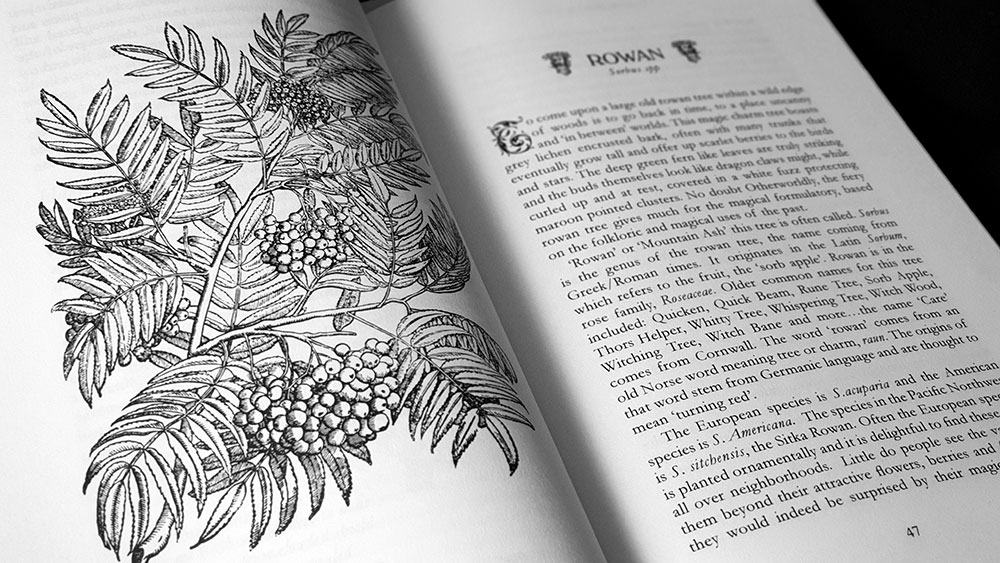

Formatting in The Well of Light by Jenny Stracke (who also provided copy editing) is unspectacular but supremely functional, set in a large serif face with subheading, section headings and chapter headings in bold and small cap variations of the same. This capable hand is less obvious on the cover with its mess of typefaces and gradient background against which cover art by Martin Bridge is unflatteringly placed. Bridge also provides the book’s few internal illustrations, with various heavy-lined vector diagrams in the Mystery of the Double Rose section.

Published by R.J. Stewart Books