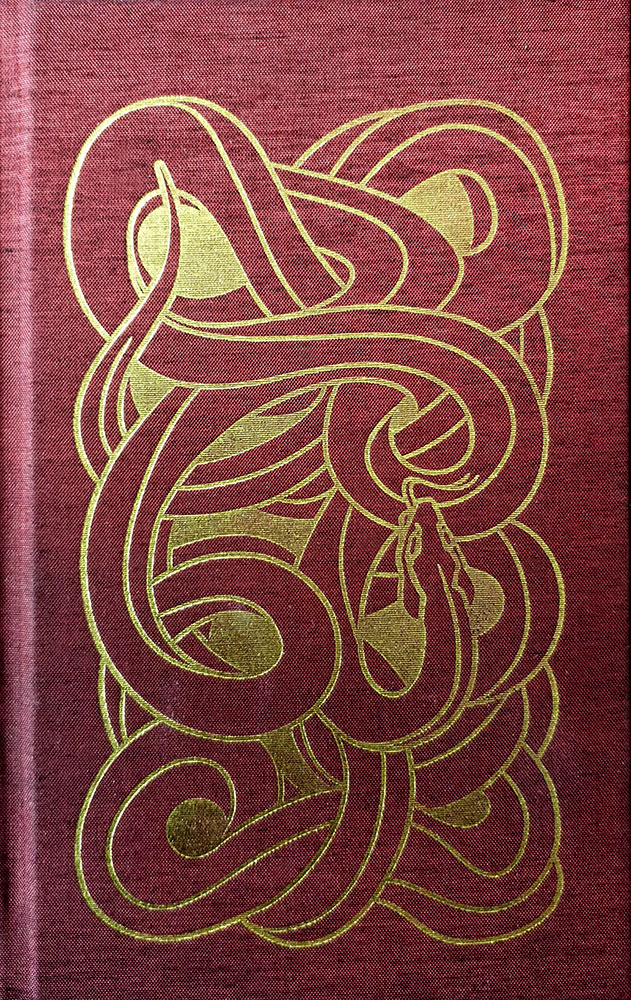

Originally released by Ouroboros Produktion in 2002 as Uthark: Nightside of the Runes, this book has had its title flipped, and its page count inflated, by Inner Traditions; a publishing house that is home to a surprising amount of runic content alongside more conventional metaphysical fare. To do this, Nightside of the Runes takes the original content of Uthark, and adds a second part based around the Adulruna, and Gothic Cabbala of the subtitle. The latter is Thomas Karlsson’s Adulrunan och den Götiska Kabbalan, a work previously available only in Swedish, German and Italian. And fun fact, the cover here more resembles that of the original edition of Adulrunan och den Götiska Kabbalan than it does Uthark: Nightside of the Runes.

Originally released by Ouroboros Produktion in 2002 as Uthark: Nightside of the Runes, this book has had its title flipped, and its page count inflated, by Inner Traditions; a publishing house that is home to a surprising amount of runic content alongside more conventional metaphysical fare. To do this, Nightside of the Runes takes the original content of Uthark, and adds a second part based around the Adulruna, and Gothic Cabbala of the subtitle. The latter is Thomas Karlsson’s Adulrunan och den Götiska Kabbalan, a work previously available only in Swedish, German and Italian. And fun fact, the cover here more resembles that of the original edition of Adulrunan och den Götiska Kabbalan than it does Uthark: Nightside of the Runes.

The concept of the Uthark has its origins in the work of Swedish poet and runologist Sigurd Agrell, who argued that the runes should be ordered, not with Fehu at the start, but at the end, thus beginning with Uruz to make an uthark not a futhark. While there are a few examples of a sequential listing of runes in which they could begin with Uruz instead of Fehu, these may simply be errors or erosion, such as, most famously, the Kylver stone from Gotland, where a vertical line before the Uruz could be the remains of Fehu. Karlsson himself doesn’t labour much for the validity of the theory, saying that irrespective of how it is held, the Uthark is a magically potent version of the rune row that corresponds well with Old Norse language and myth.

Perhaps the most interesting application for the Uthark is in how it changes things numerologically, with the value of each rune moving one along when using a letter-to-number cipher, with, for example, Hagalaz becoming a more pleasing 8 and Nauthiz a fitting 9. On the other hand, confirmation bias, pareidolia and apophenia being what they are, you could probably work out some esoteric significance betwixt a rune and a certain value no matter what number it was assigned.

Despite the title of this half of the book (and of the previous standalone edition), the Uthark doesn’t always play a huge role here, save for the occasional esoteric nugget that can be assigned to runes and the reshuffled aetts. Instead, this is a general rune magic primer, with everything you would expect in it: a section on the meaning and symbolism of each rune (and another variation of this same listing later on with meanings simplified for the purpose of divination), a brief guide to runic yoga in the style of Friedrich Marby, an exploration of the cosmology of the nine worlds, and a guide to ritual, including brief considerations of galdr and seiðr. The most notable innovation here is Karlsson’s presentation of the Uthark order of runes as a journey to Hel along the Helvegr, with each rune marking a stage on the journey, beginning with Uruz as a fitting gate to the underworld and ending with the less satisfying interpretation of Fehu as the magician in their state of completion.

The original body copy of Uthark has been edited for this release, tidying up and finessing the words here and there, but not going all out and altering Karlsson’s voice as it appears in the original, translated by Tommie Eriksson (whose name doesn’t seem to be credited in this new edition). As a result, the writing still comes across as the work of someone with English as a second language, though not horribly or unforgivably so. Phrasing can be a little awkward at times, and sentences are often short, abrupt eruptions, where another writer would have combined two or more of them together for greater flow.

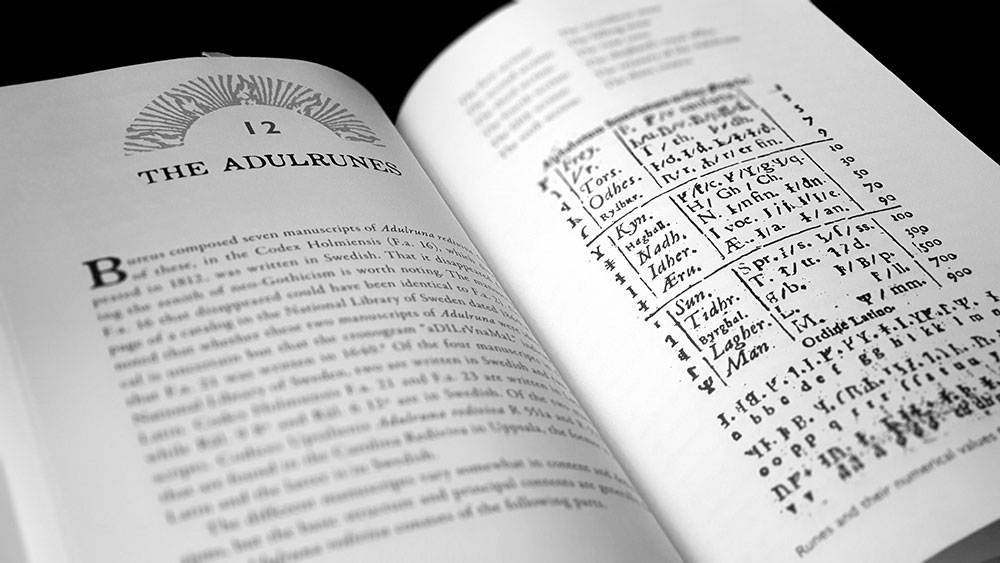

Having previously read Uthark, but not Adulrunan och den Götiska Kabbalan, it is the latter that proves the most exciting part of the book to get to. Karlsson gives something of a prelude to this in the Uthark section with a brief chapter on runosophy and cabbala, which does introduce some redundancies when you get to Adulrunan proper. While the book’s first half is indebted to Sigurd Agrell, in the second half that role is performed by the Swedish antiquarian and polymath Johannes Bureus. Agrell and Bureus share certain similarities, despite the gulf of centuries, being figures possessed of a singular vision and unique interpretations of the northern mysteries. Both created innovations of the existing futharks, with Agrell’s one-place-along shuffling of the runes of the Elder Futhark having a parallel in the work of Bureus, who grouped the runes of the Younger Futhark into sets of five, and removed the inconvenient final sixteenth rune, Yr, to make a symmetrical three rows of five Adulrunes, as he called them.

Stephen Flowers provides prologues to both the Uthark and Adulrunan sections of this book, and also acts as the translator for the latter. His introduction to Adulruna is quite substantial, running to ten pages and providing what follows with a thorough context, highlighting the cultural and hermetic milieu from which Bureus, and the broader field of esoteric Gothicism (as Karlsson calls it), emerged. With Flowers providing the translation, The Adulruna and the Gothic Cabbala does feature a significant change in Karlsson’s voice from that of Uthark, lacking the staccato quality, with sentences now flowing longer and smoother.

The other noticeable difference is a considerably more academic approach, with the content here forming the basis of Karlsson’s 2010 doctoral thesis Götisk kabbala och runisk alkemi: Johannes Bureus och den götiska esoterismen. This is particularly evident in the first chapters of The Adulruna and the Gothic Cabbala which consists of an academic literature review of Bureus and Gothicism in general, and is then followed by a citing-heavy chapter defining Western Esotericism and name-checking all the usual suspects (Dame Frances Yates, Antoine Faivre, Henrik Bogdan, Wouter Hanegraaff, Mercia Eliade etc.). This makes for two very different halves of a book, with the academic grounding of the second half contrasting strongly with the practical, hands-on enthusiasm of the first.

It is the hermetic influences that played a large role in what Bureus created, with esoteric Gothicism drawing on elements of alchemy, cabbala, astrology and ceremonial magic; including clear nods to figures who loom large within this pantheon such as Paracelsus and Dr John Dee. As such, Bureus makes a fitting role model for Karlsson, whose Dragon Rouge organisation has a similar eclectic approach, employing elements of cabbala, including the nightside, and goetia, but with a strong focus on indigenous Scandinavian traditions.

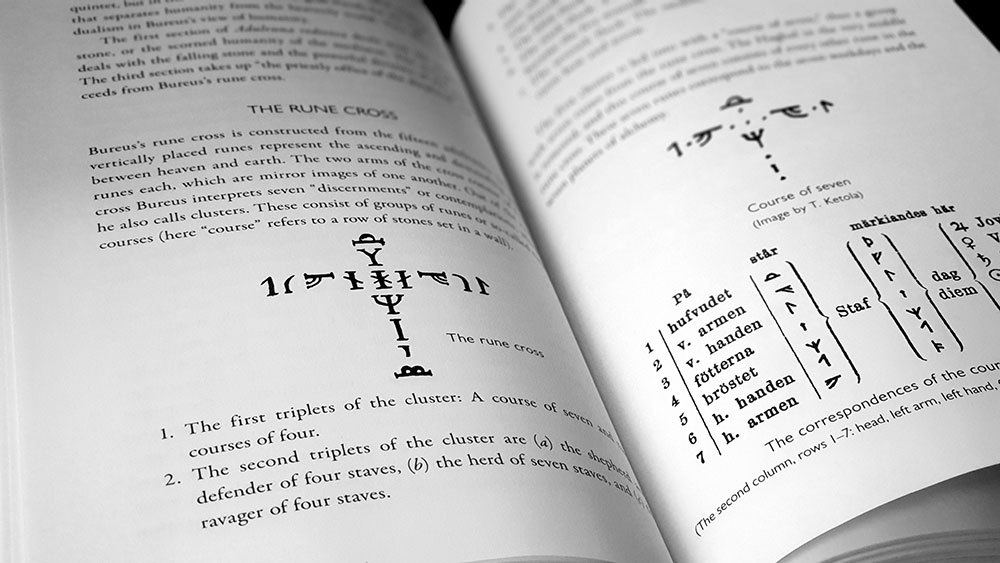

Bureus’ system involves a dense, interwoven cosmology and a very specific nomenclature that is, to put it mildly, idiosyncratic; and Karlsson does an admirable job of documenting it thoroughly and as clearly as can be done with something as ornamented as it is. For example, Bureus posited a rather unique take on the Germanic pantheon in which, based on the runic formula of TOF, Thor was the preeminent god (an androgynous combination of feminine and masculine worshipped since “primeval times” as the “great invoker”), while Odin and Fröja were his children and messengers. This, as was the style of the time, then incorporated elements of mystical Christianity, with Fröja as the Holy Spirit and Odin as a version of Christ, the son of God, who descended into flesh and then returned, ascending to heaven, providing, as mediator, a process for others to follow. Bureus argued that this reflected a version of the philosophia perennis which had remained pristine in the north far longer than in the lands to the south. This incarnation was eventually corrupted when a wandering master of witchcraft and his wife assumed the names of Odin and Fröja. They received worship and turned this pure proto-Christianity into heathenry with its dreaded worship of wooden idols (and worst of all, changing the order of the formula to FTO, with Fröja now worshipped at the beginning of life, Thor during life itself, and Odin at old age and death).

Suffice to say, there’s not a lot of value to Bureus’ system if you’re purely pagan in orientation, or if you adhere to the archaeological record, with his conception of Germanic belief being, to put it diplomatically, highly speculative. But it is, if nothing else, fun. And that’s what makes Nightside of the Runes a worthy purchase, as it provides perhaps the most accessible and in depth information in English on Bureus’ convoluted cosmology and interpretation of the runes; as well, of course, as Agrell’s slightly less esoteric Uthark.

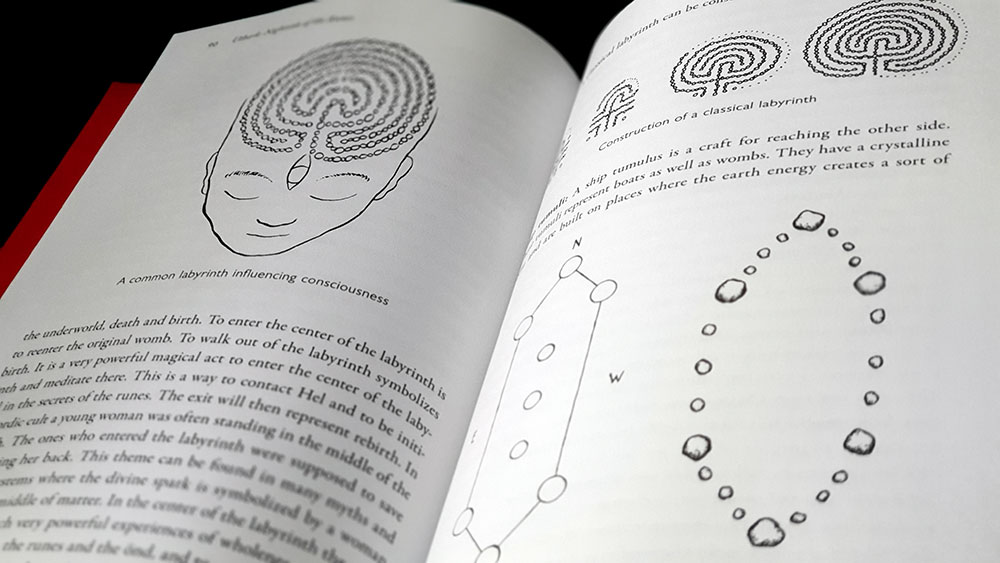

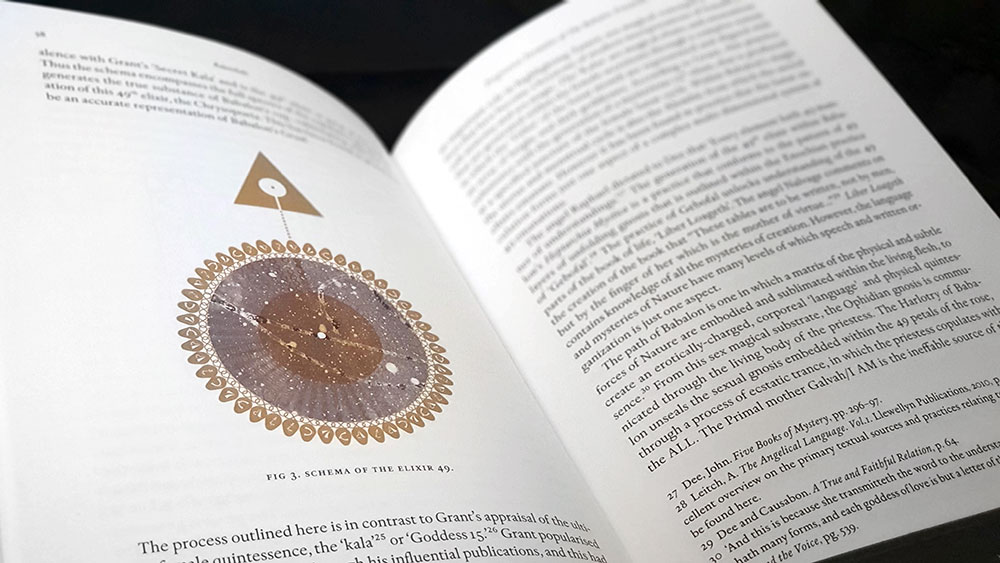

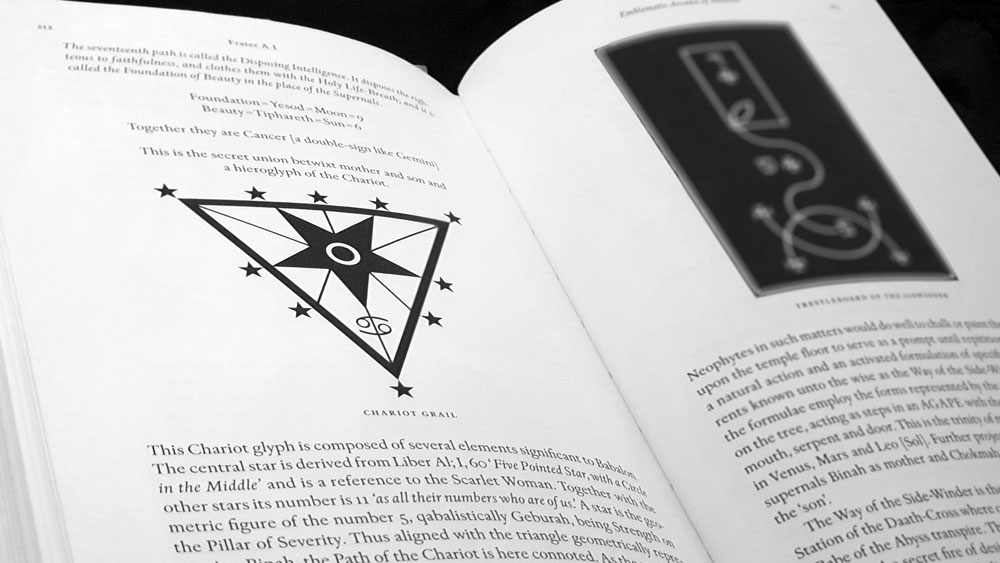

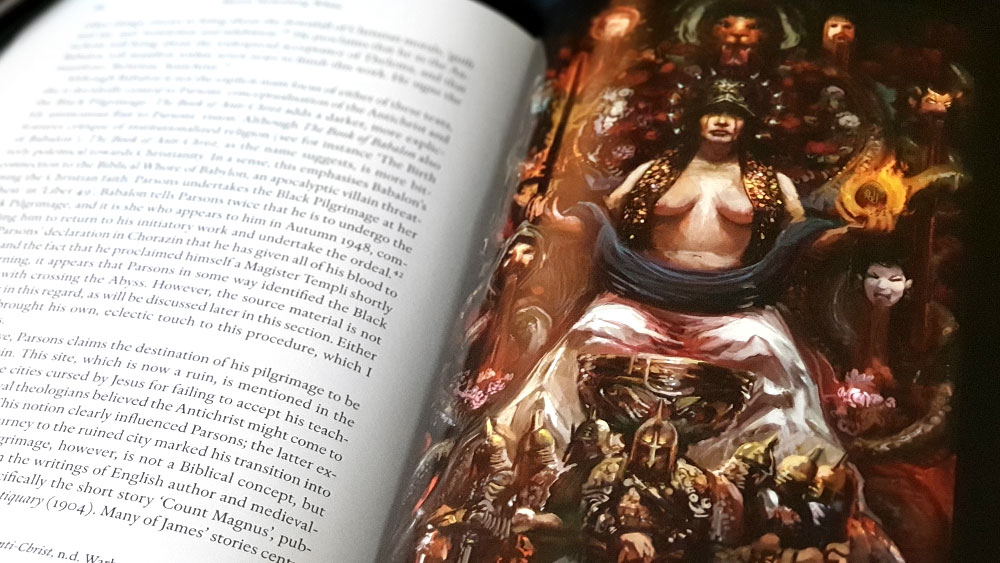

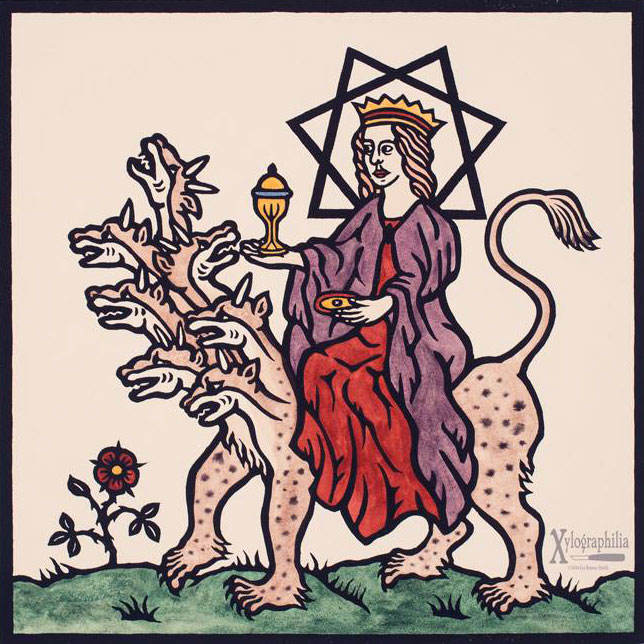

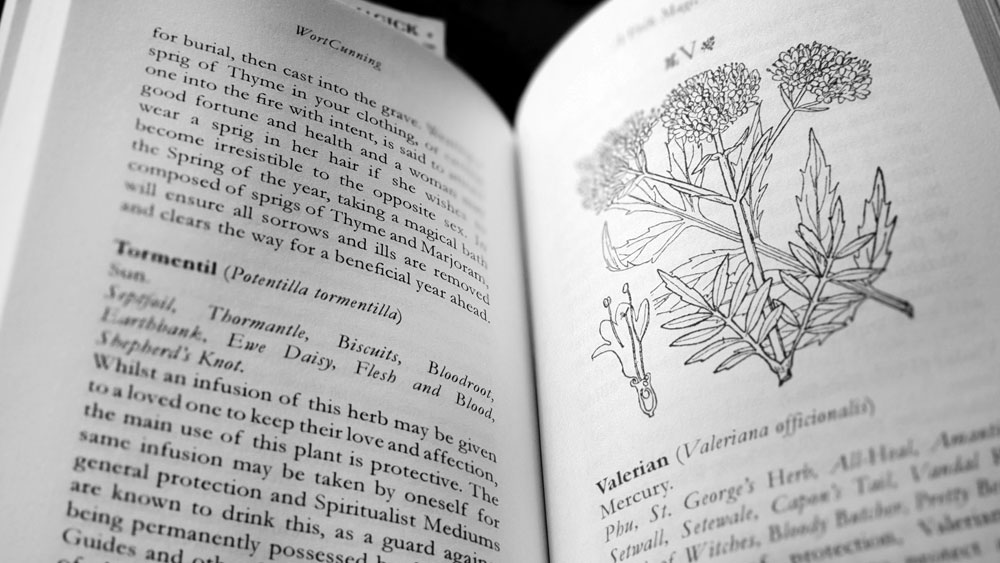

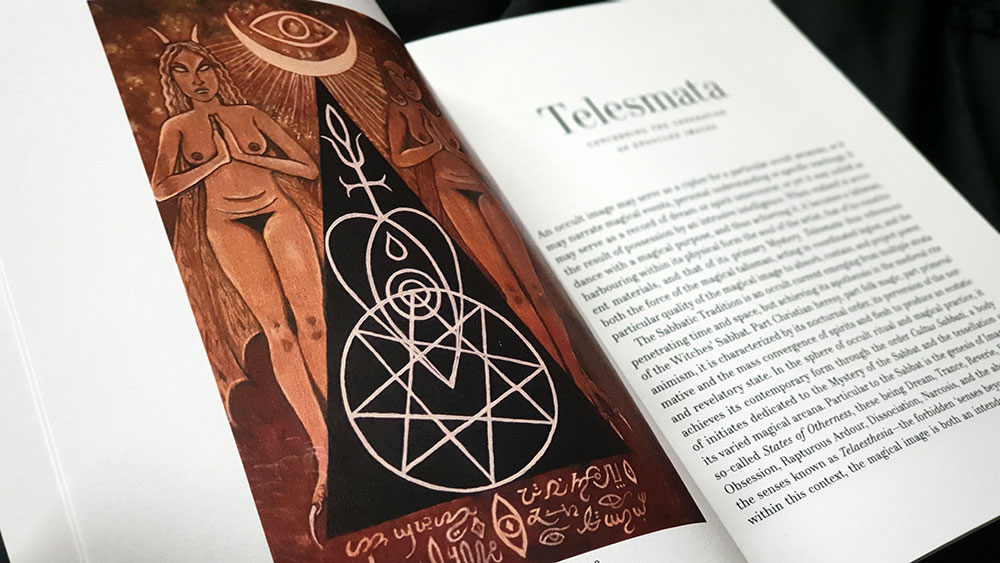

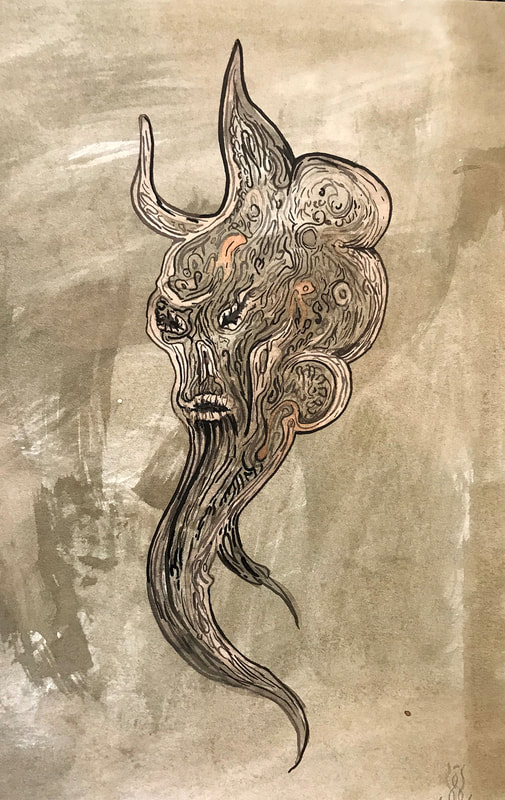

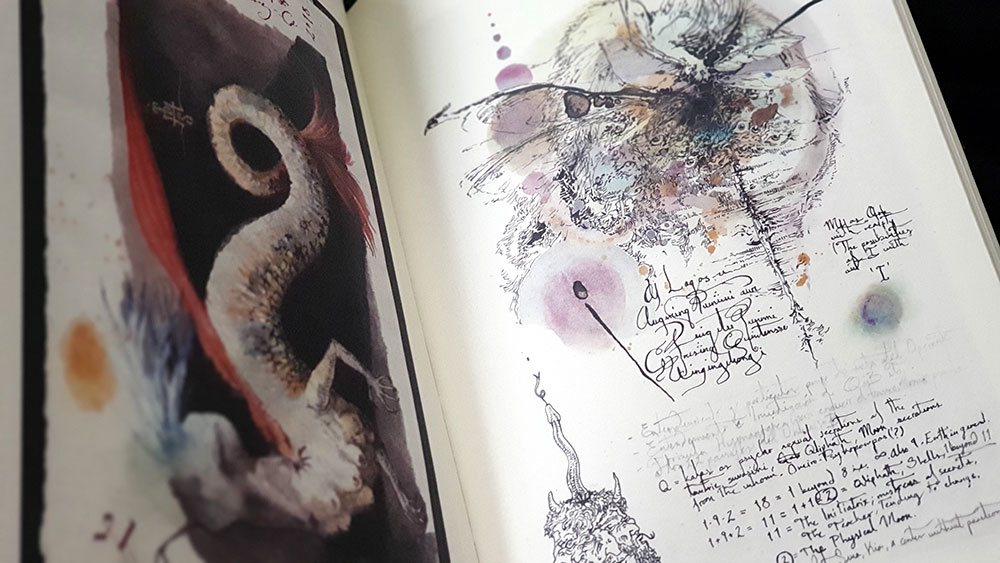

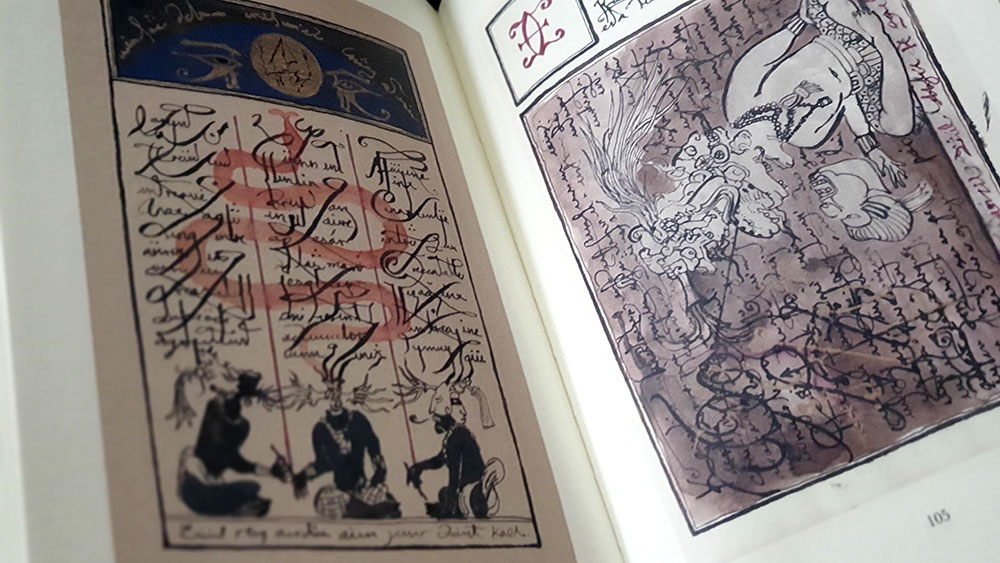

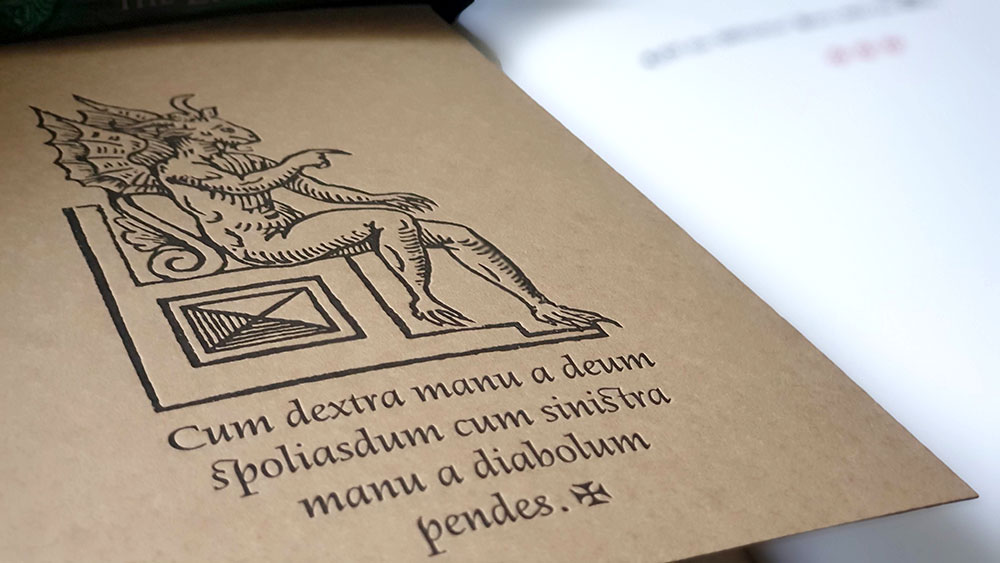

Illustrations in Nightside of the Runes consist of the original line drawings from the original edition of Uthark in the first half, and an exhaustive collection of images from Bureus’ publications in the second. These are rendered in black and white with the contrast turned well up to remove any colour or texture of the original print material, thereby giving them a consistent weathered and arcane look.

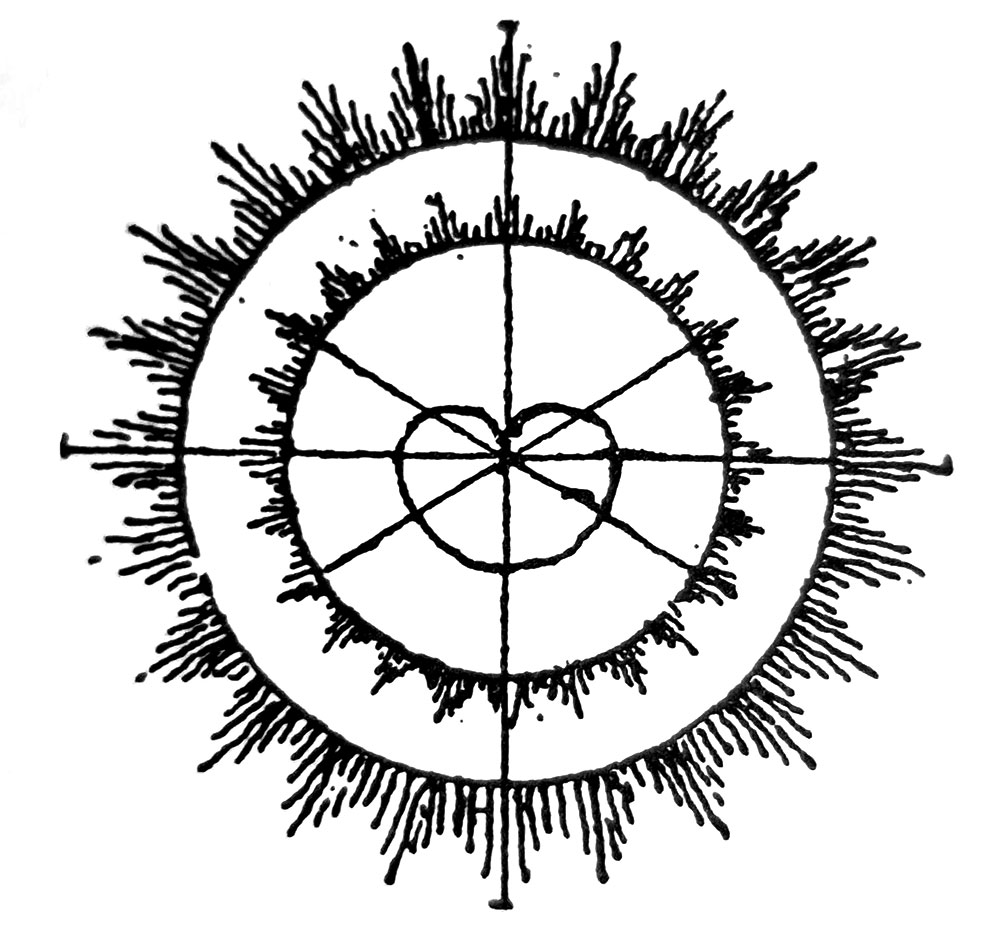

Nightside of the Runes is available in Kindle and hardback versions, with the latter wrapped in a dustjacket over its black boards and the title foiled in silver on the spine. Layout is by Inner Traditions’ Debbie Glogover with the body in a dependable Garamond, and headings in a distressed Appareo that contrasts with the san-serif Gill Sans of the subheadings. Appareo is a nice touch with its almost-slab serifs and worn edges approximating the face used on the original edition of Adulrunan, and conveying less of the runic side of this book and more of a sense of the later gothic manuscript or grimoire. Continuing this style, each chapter heading incorporates a crop of the sun image from the book’s cover (originally from the title page of Bureus’ Svenska ABC boken medh runor), sitting above the title as a pleasing archway.

Published by Inner Traditions

Review Soundtrack: Therion – Gothic Kabbalah (as with many Therion albums, Thomas Karlsson provided the lyrics to this album based on the work of Johannes Bureus)