The prospect of a long lost tarot deck designed by Austin Osman Spare is a tantalising one, and for this reader at least, guaranteed a rush to the Strange Attractor Press preorder page. Once it was finally released and it turned up in the mail I had made it all the way to the “what the hel is this package” phase.

The prospect of a long lost tarot deck designed by Austin Osman Spare is a tantalising one, and for this reader at least, guaranteed a rush to the Strange Attractor Press preorder page. Once it was finally released and it turned up in the mail I had made it all the way to the “what the hel is this package” phase.

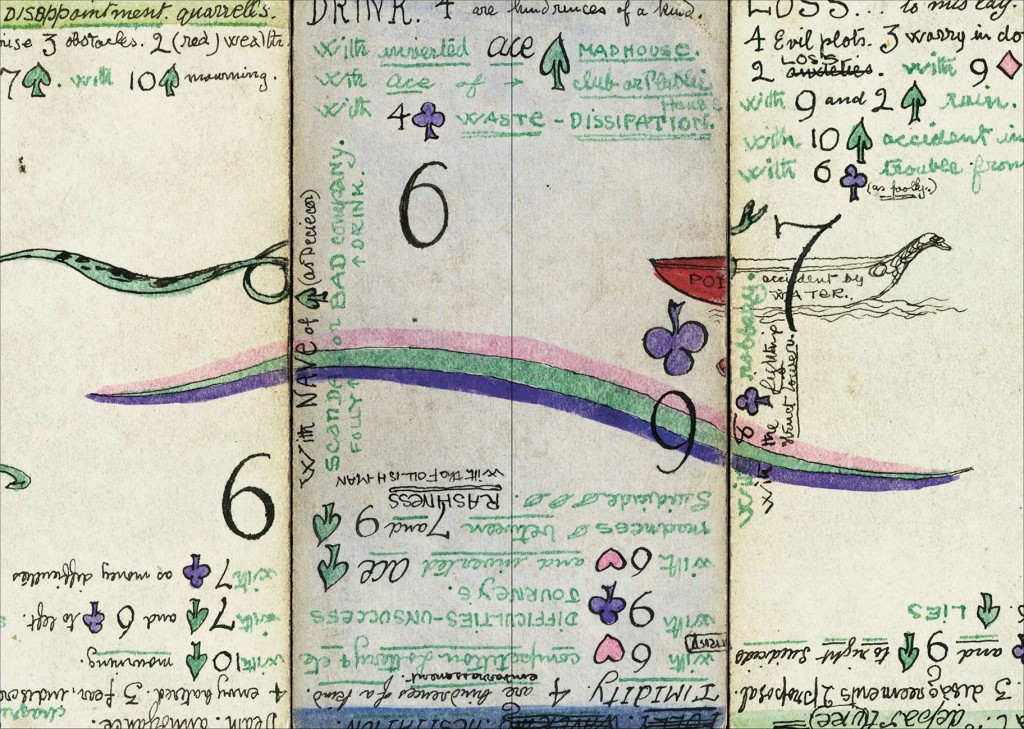

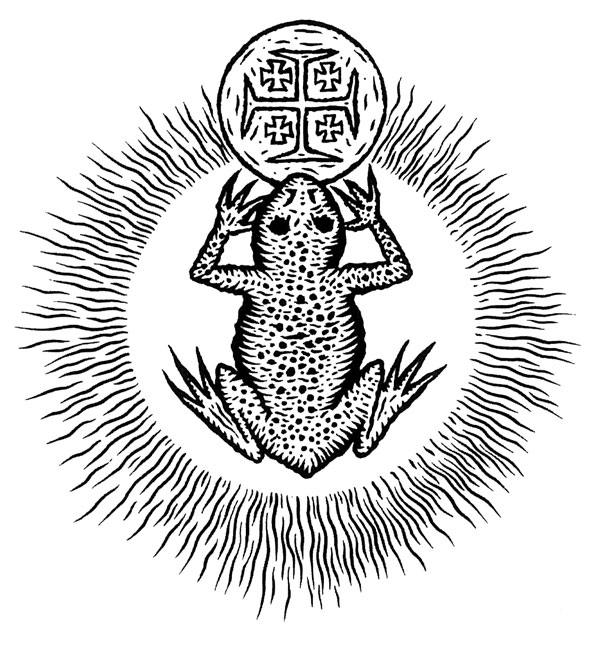

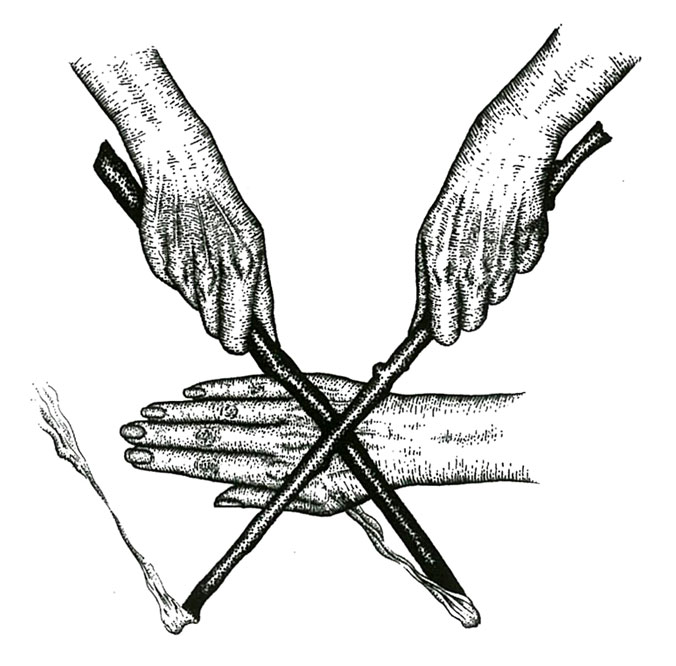

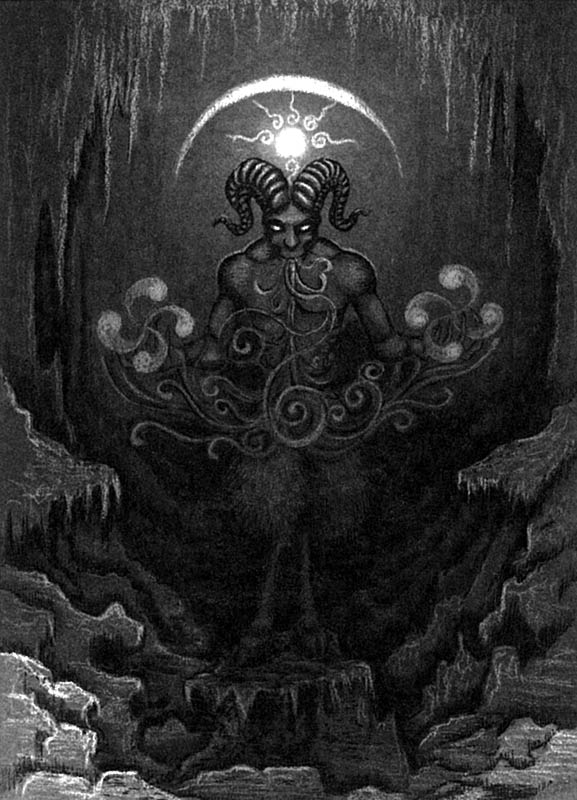

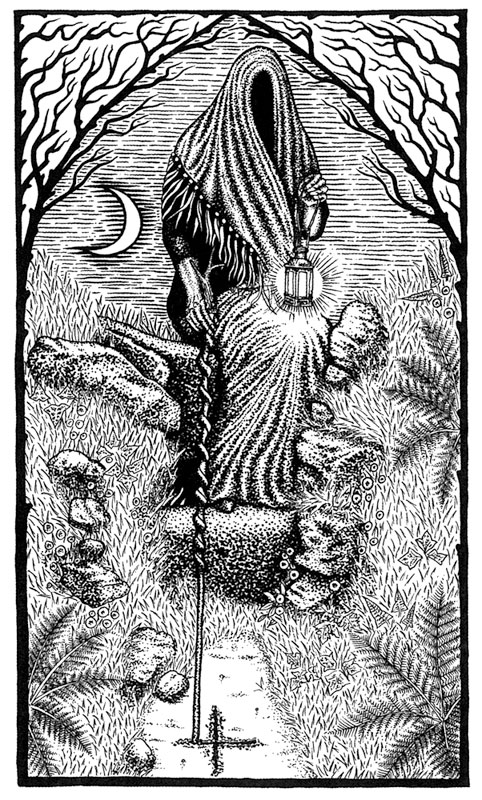

If the thought of a Spare-designed tarot deck makes you imagine classic Sparean images, all crisp phantasmagorical lines against a white background, then temper your expectations. The look of the cards is a denser one than that, with the style, while obviously in Spare’s hand, being more traditional, and made heavier with a thorough use of watercolour washes on both figures and backgrounds. The deck is also arguably more traditional than either Crowley’s Book of Thoth, or anything one might expect from the proto-Chaote that is Spare, with the Major Arcana images obviously drawing, for the most part, on the atu of the Tarot de Marseille and its antecedents. The Minor Arcana, on the other hands, reveals the cartomantic roots of Spare’s praxis, adopting the suits of traditional playing cards and adding four court cards of queen, king, knight and knave to each set. Perhaps the strongest diversion from convention, though, is the text heavy nature of the hands, with Spare scrawling interpretations and instructions at the foot and head of each card, reflecting the orientation of the reading.

But first, the provenance of this deck and why it was lost. To the latter question first, it wasn’t so much lost, and instead has been sitting quite contentedly for over 70 years in the collection of the Magic Circle, the famed London organisation for those magicians of the stage, and not the ritual chamber, variety. Editor Jonathan Allen, a curator at the Magic Circle museum, rediscovered the archived deck in 2013 and this volume reproducing the cards and featuring commentary from a number of essayists, provides the first broad exposure of Spare’s tarot.

The written contributions in Lost Envoy take two forms: archival documentation and analysis. The former includes Spare’s Mind to Mind and How, by a Sorcerer and Arthur Ivey’s Tarot Cards and a Pack in The Magic Circle Museum from the November 1969 issue of the Magic Circle’s in-house magazine The Magic Circular. Spare’s essay is an unpublished submission for the long running London Mystery Magazine, and provides a practical guide to cartomancy as well as giving a sense of the methods behind the creation of this deck. Ivey’s brief essay uses half of its two page length as a history of the tarot which prefaces an all too brief description of Spare’s tarot, creating a museum catalogue entry as it were.

Given that the two documents provide the only extant historical information about Spare’s tarot and his methods, they are referenced extensively in the accompanying essays, creating something of a sense of déjà vu. This is exacerbated by the ultimately limited amount of things that can be said about Spare’s tarot, meaning that many of the same points are familiarly made across multiple essays. Both Helen Farley and Gavin Semple’s contributions cover the provenance of the deck and Spare’s nascent involvement in the occult milieu of Victorian London, each then followed with a little analysis of some of the cards and their characteristics. A more focused consideration of the cards themselves is provided by Phil Baker’s His Own Arcana, with his points ably reinforced with the inclusion of full colour images of the trumps and full bleed plates of details.

The Deputation by Sally O’Reilly takes a different approach from its companions, with an imagined encounter between Spare and his friend, the suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst. Spare and Pankhurst sit and engage in witty banter about his cards, with her queries allowing him to provide the explanatory exegesis. It’s a diversion whose mileage may vary depending on one’s patience for the conceit of words put into the mouths of historical figures; especially given that their tone and mores are inevitably predicated by the lens of today.

The final essay comes from Alan Moore who, with A Cartomantic Mirror, provides a pretty exhaustive tarot reading of the meaning and intention of Spare’s deck using, and it gets pretty damn meta here, Crowley and Harris’ Thoth deck. Again, no expense has been spared and the cards drawn from the Crowley/Harris deck are reproduced here in full colour, with some key atu each given a page to themselves.

The essays take up only half of this volume’s 336 pages and the remainder is comprised of reproductions of Spare’s cards. These are presented first as full pages reproductions of each of the major and minor arcana, and then followed by six examples of the various coloured card backs. For extra thoroughness, the cards are then presented again in a concordance that transcribes all of the textual data found on the cards, one page for each, along with a listing of marginal links that tie one card to another, and meticulous footnotes providing still further information. Between some of these individual pages are full colour folded inserts of some of the cards, showing the way in which Spare graphically linked the designs together across multiple spreads. This is one of those things that reveals the attention to detail that has gone into producing this volume, with an almost unnecessarily thorough presentation of the data.

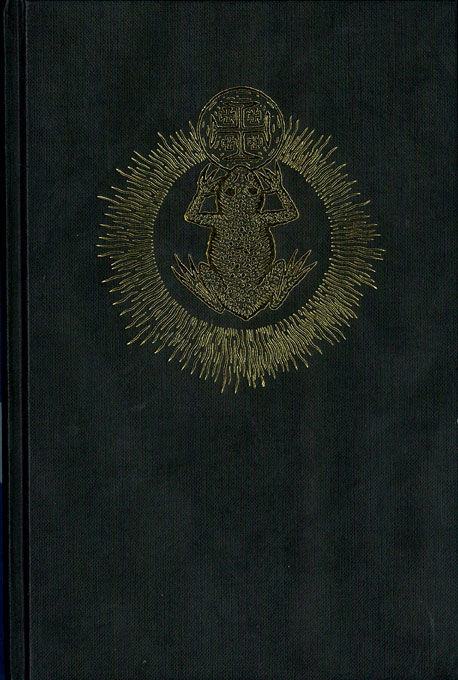

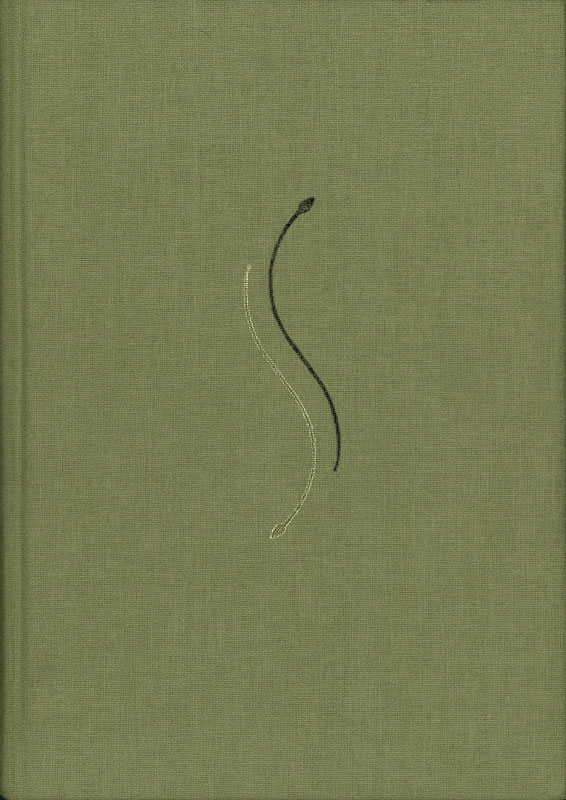

Lost Envoy has been designed by Fraser Muggeridge studio, with a cover that appears a strange, jarring melange of geometric colour until one realises, as this late junction, that it shows a cascade of Spare’s multi-coloured card backs. The book is bound with, apparently, a period binding common to many of the volumes found in The Magic Circle library, with a gold deboss of Spare’s autographic bird’s head sigil (no, not the cool vulture one, the one that looks like Montgomery Burns). The text formatting inside the book is not entirely satisfying, with the body copy rendered in a far too modern sans serif typeface which isn’t conducive to reading and gives the impression, false though it may be, of text being dumped in from a Word document with Calibri set to default. With this are awfully snug header and footer margins, due to the page numbering being put on the outer edge, which again, and contrary to the intent, feels like the default settings in a Word doc, rather than something carefully designed. Otherwise, a lot of effort has gone into the production of this book, with the cover text debossed (and the aforementioned sigil debossed and foiled too), a beautifully raised emboss on the inside cover page bearing the Magic Circle logo, not to mention the preponderance of colour prints and the inserted replicas of cards.

With its repeated representation of the cards in Spare’s deck in both graphic and textural forms, it’s clear that the intent of this book is one of complete and thorough documentation, in which the cards are presented in the best possible light for posterity. Whether anyone is going to read the transcribed page for each card isn’t the point, and this reviewer certainly didn’t. Instead the point is that it’s there should one need it. In this way, the essay content is almost secondary, and it is the cards themselves that tell the story.

Lost Envoy was made available in two editions: a standard hardback edition still available with 336pp pages, fully illustrated in colour, with over 200 images. And a now sold out numbered and debossed edition of 300 copies, with fold-out sections.

Published by Strange Attractor Press