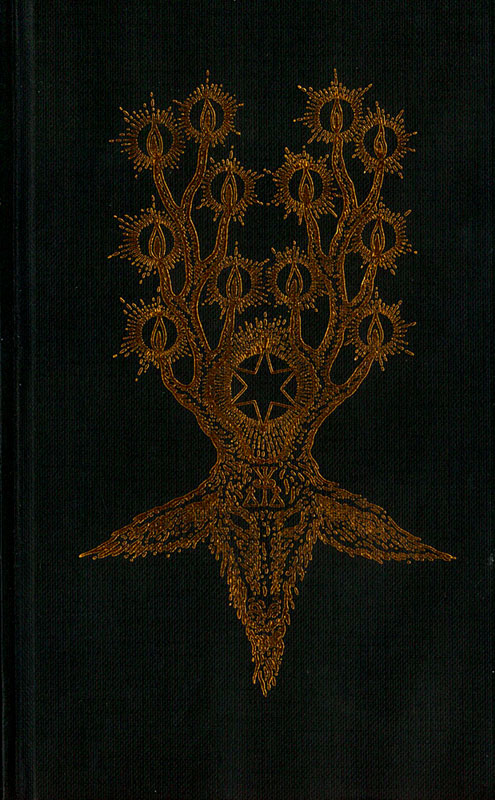

This compendium of essays on the role of Lucifer in Western Esotericism represents the last significant contribution to occult publishing by Michael Howard before his passing in 2016. In addition to his role as co-editor, he provides an essay and is joined by Frater U.:.D.:., Robert Fitzgerald, Ethan Doyle White, Fredrik Eytzinger, Richard Gavin, Raven Grimassi, Lee Morgan, and Madeline Ledespencer.

This compendium of essays on the role of Lucifer in Western Esotericism represents the last significant contribution to occult publishing by Michael Howard before his passing in 2016. In addition to his role as co-editor, he provides an essay and is joined by Frater U.:.D.:., Robert Fitzgerald, Ethan Doyle White, Fredrik Eytzinger, Richard Gavin, Raven Grimassi, Lee Morgan, and Madeline Ledespencer.

The Luminous Stone is the third entry in Three Hands Press’ Western Esotericism in Context series, following on from previous explorations of Babalon and Traditional Witchcraft. As with any compendium such as this, the most interesting contributions are ones that explore territory less travelled. Any consideration of the usual biblical or folkloric accounts, and the intersection thereof, are going to be pretty uninspiring, without much, if anything, new to offer. Mercifully, there are instead several explorations of completely alien territory. Such territories are ones in which the Luciferian spirit of inventiveness seems to have been fully embraced by its adherents, with each providing something of an idiosyncratic interpretation.

The occult scene of 19th century Paris as described by Madeline Ledespencer is a prime example of this, with Ledespencer showcasing two figures, L’Abbé Boullan and Maria de Naglowska, each with a Luciferian supra or subtext, but each with a unique take on it. After a less than stellar start from this volume’s first two contributors (English as a second language for one, and just a bit stilted for the other), Ledespencer’s piece is refreshingly well written, with an ebullient style that reads easily and conveys a sense of both the love and knowledge she has for her subject matter.

As one would expect from a Three Hands Press book, there’s the occasional nod to the Cultus Sabbati and the work of Andrew Chumbley. Robert Fitzgerald’s The Hidden Stone: Devotion, Lucifer and the High Sabbat uses the Cultus as an example of a modern witchcraft sodality with a particularly Luciferian anatomy, focussing, by way of example, on Chumbley’s rite A Lover’s Call to the Angel of Witchblood. Fitzgerald steps through the rite line by line in order to untangle its cosmology, making a little more sense of Chumbley’ picturesque prose. In a similar area, Ethan Doyle White considers the role of Lucifer in broader contemporary pagan witchcraft, tracing the tantalising mentions from the original witch trial records into the modern era and the various works of Doreen Valiente, Robert Cochrane, and the Farrars et al.

In Teachings of the Light, Michael Howard returns to material covered in his Book of Fallen Angels, a work that seems a significant touchstone for many of the authors included here. He describes his encounters with Madeline Montalban, and gives an overview of the system of Luciferian magic from her Order of the Morning Star. This provides a little more depth than his previous discussions of her system, placing it within the context of the occult milieu in which she existed and noting the connections, for example, with the Atlantean mythos of Dion Fortune and Gareth Knight.

A less recently seen but welcomed faceless face is Frater U.:.D.:., whose piece, the gloriously titled ‘Non Seviam’ as Ontological Paradigm, oh yes, begins dryly enough, discussing Lucifer’s antinomian qualities, before briefly taking a more interesting turn and considering him in relation to the Fraternitas Saturni; of which the frater has been a member for over thirty years. It is an instance like this, where an insight is provided into an organisation’s particular understanding of Lucifer, that provide some of the most satisfying content in this book; as is the case with the essays considering the Cultus Sabbati, or Madeline Montalban’s Order of the Morning Star.

The consistently disappointing Raven Grimassi keeps the disappointment consistent with Lucifer in the Lore of Old Italy, a clumsily written piece, full of sentence fragments, redundancies, spelling mistakes and non sequiturs, always meandering without any clear direction. As highlighted in a previous review, Grimassi’s grasp of history seems casual at best. In one case he refers to the “Middle Ages and Renaissance periods” (as if they were synonymous), but then uses an event from the 17th century as an example of his claim. Another contribution also somewhat disappointing in its lack of thorough proofing is The Latent Radiance, which opens this anthology: a single sentence runs breathlessly to seven lines, there are prochronistic references to inhabitants of Canaan between 1200 and 1000 BCE as ‘Jews,’ rather than the more accurate ‘Israelites,’ and everyone is hyperbolised as ‘renowned.’ It does use the word ‘sodality’ though, which seems to be the new ‘praxis,’ given its popularity in this volume (poor ‘praxis’ only gets a single look in).

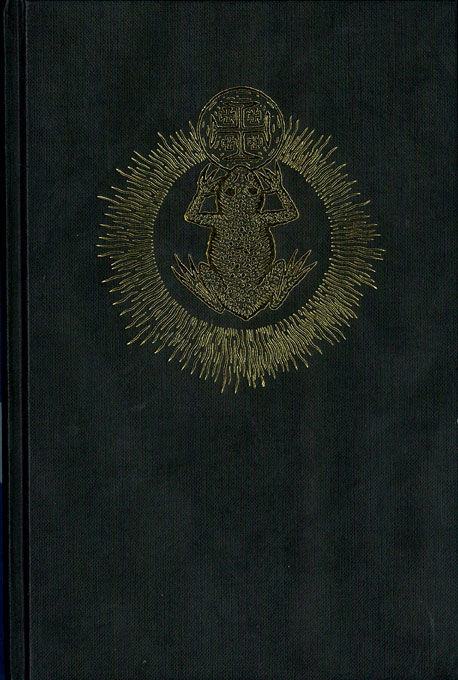

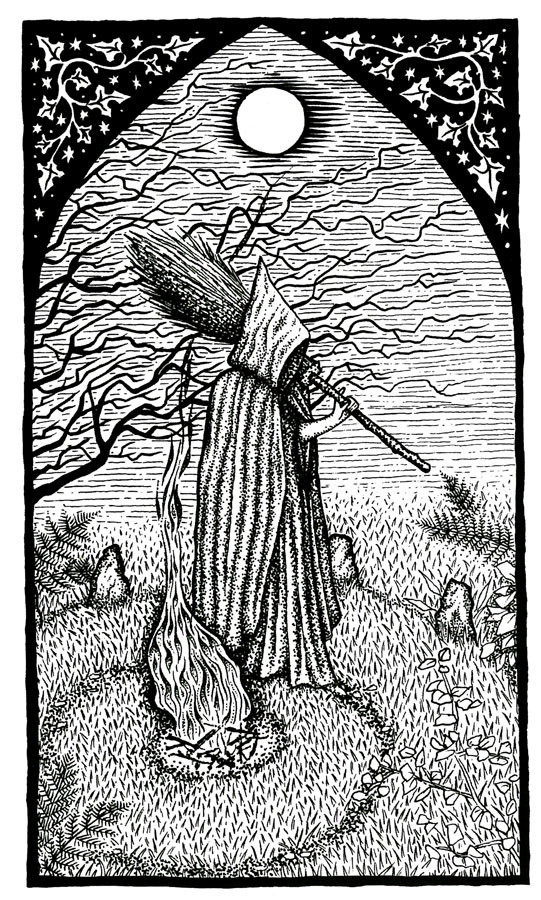

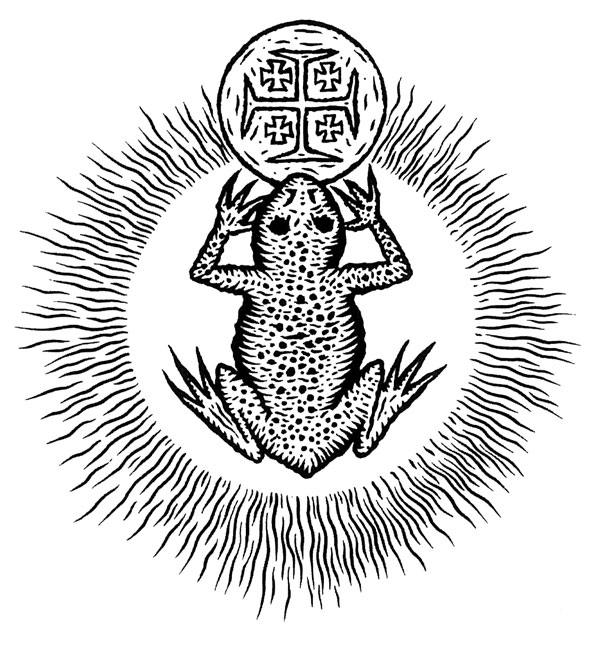

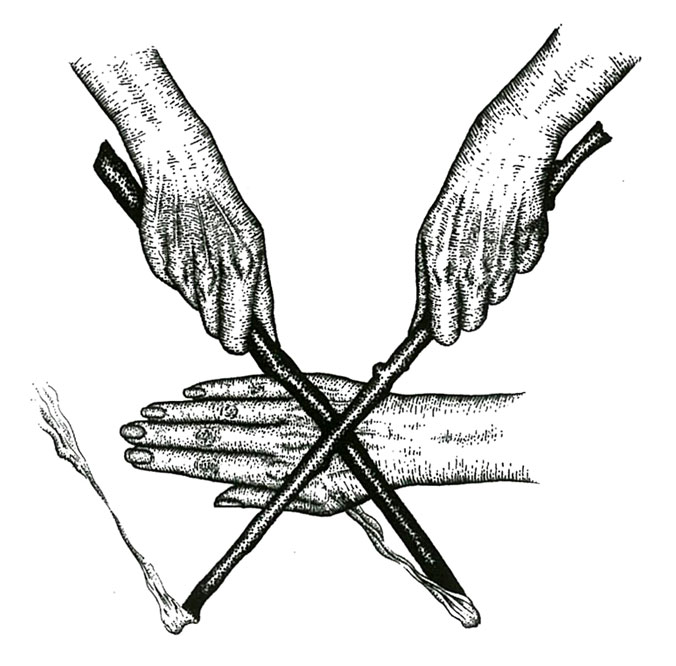

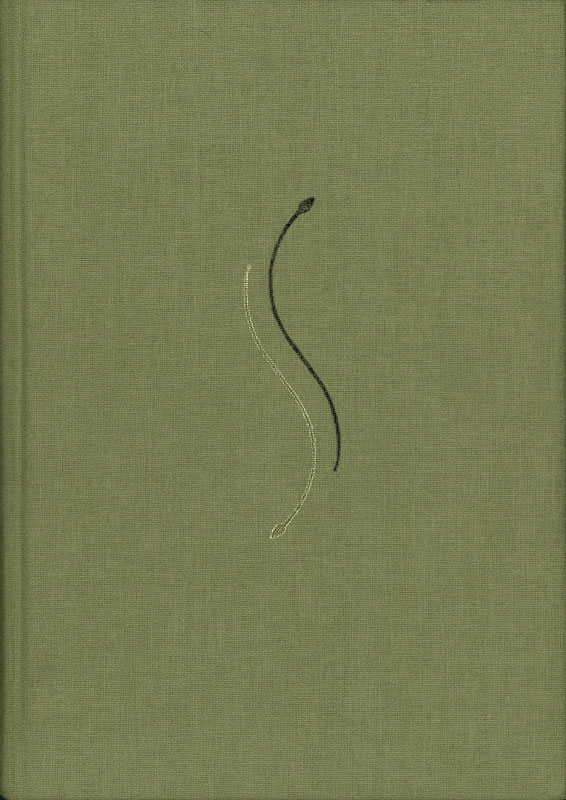

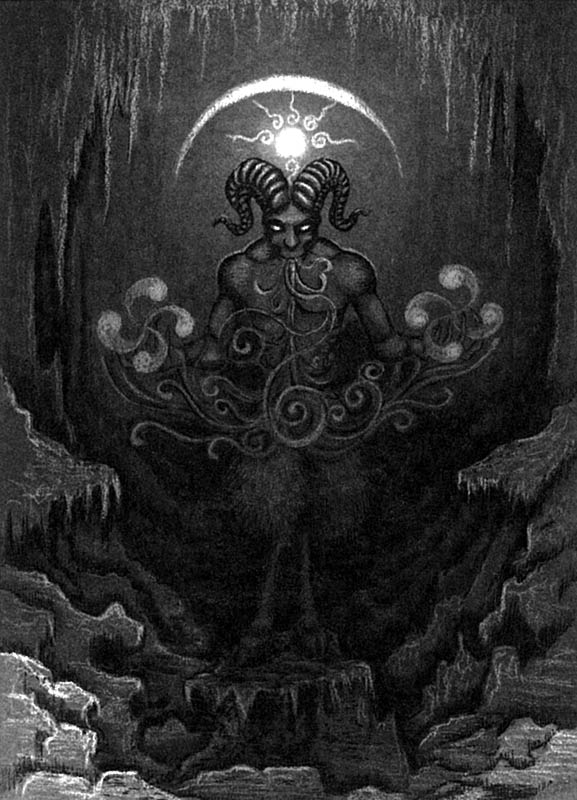

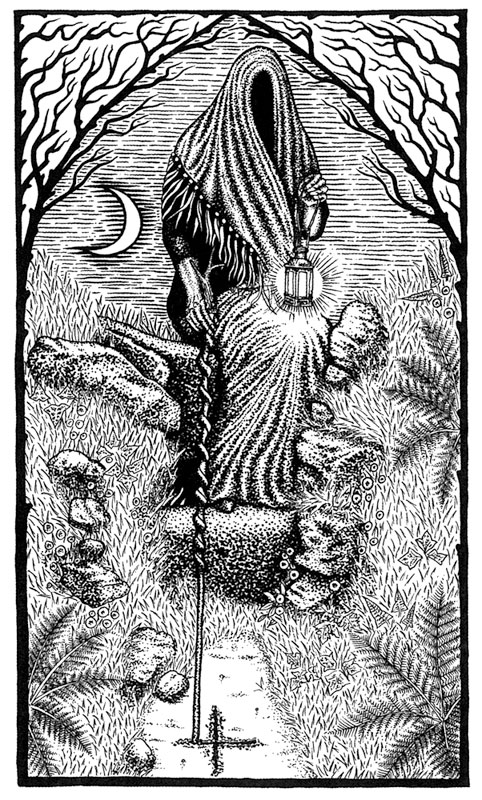

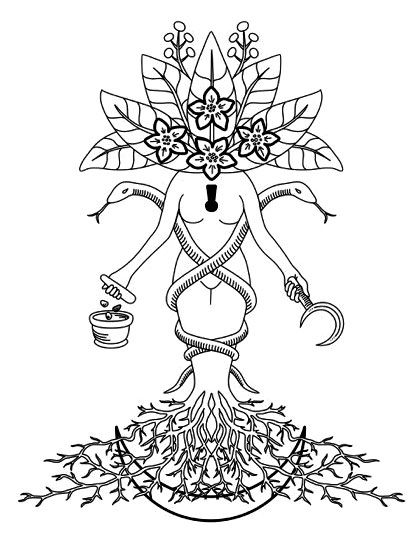

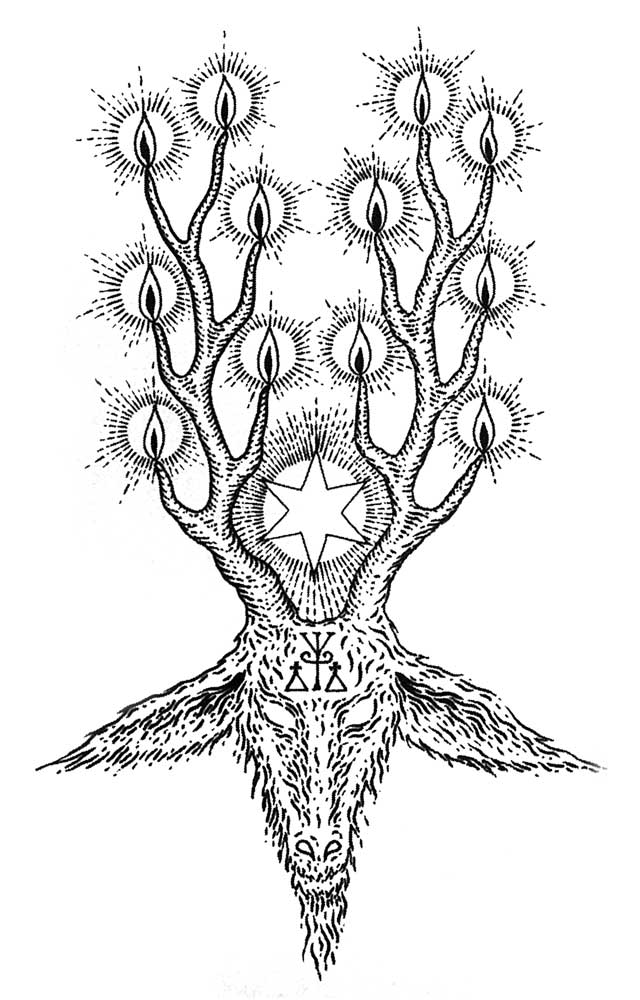

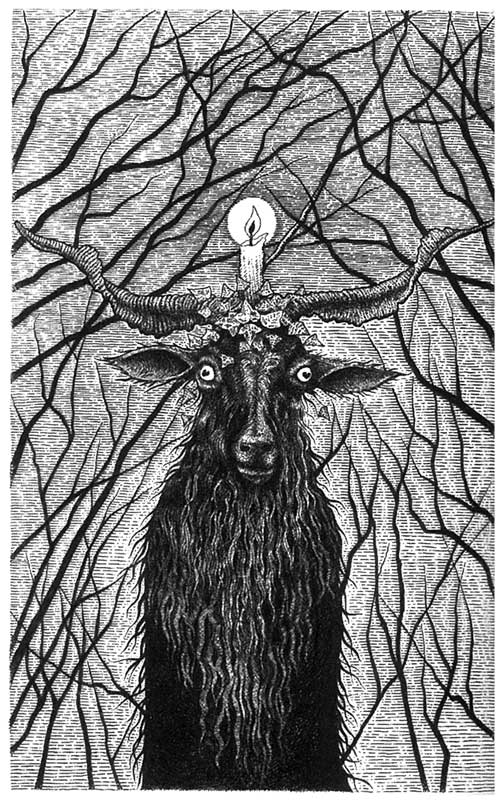

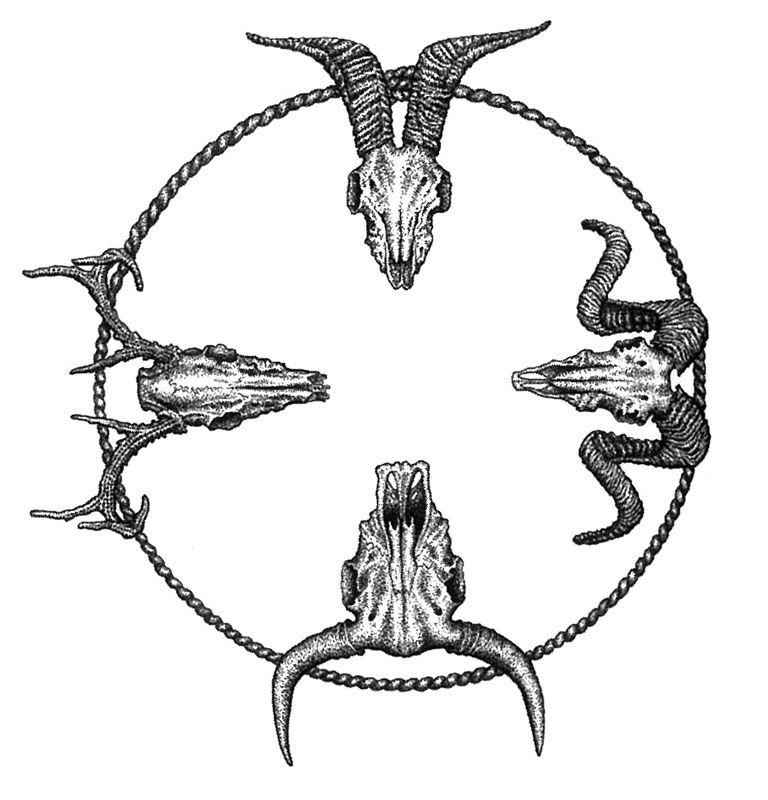

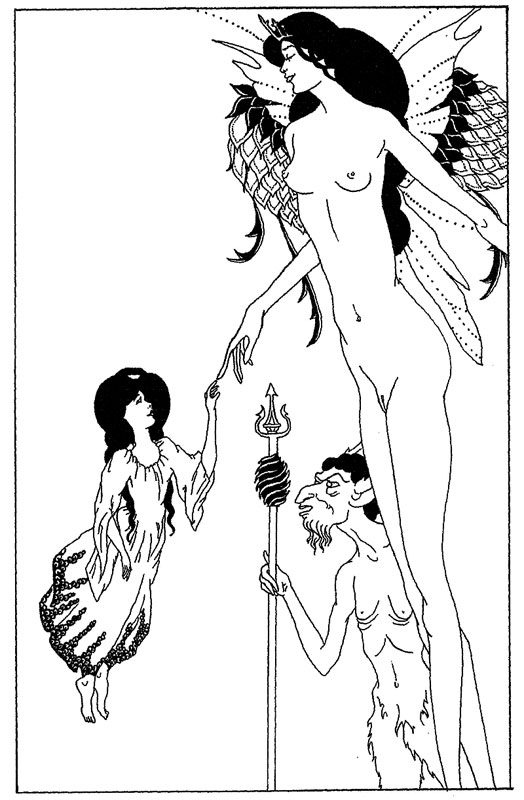

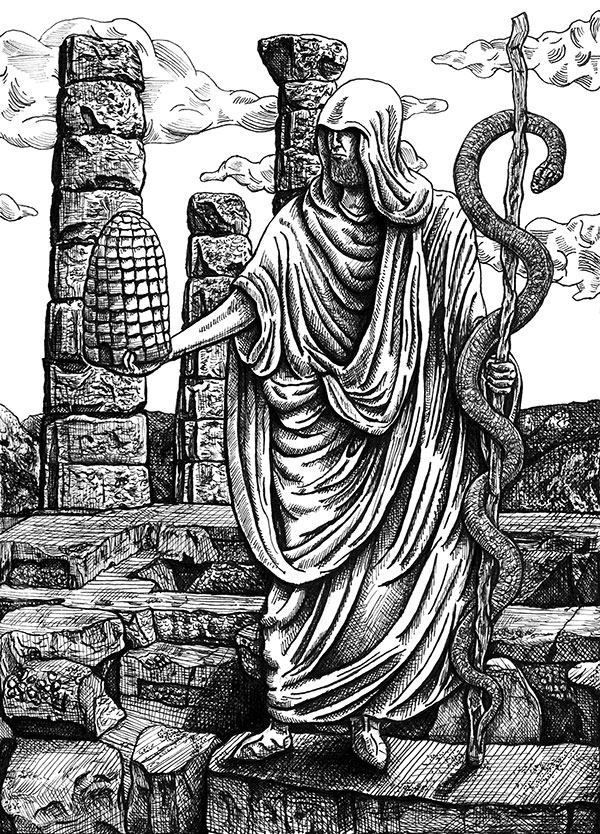

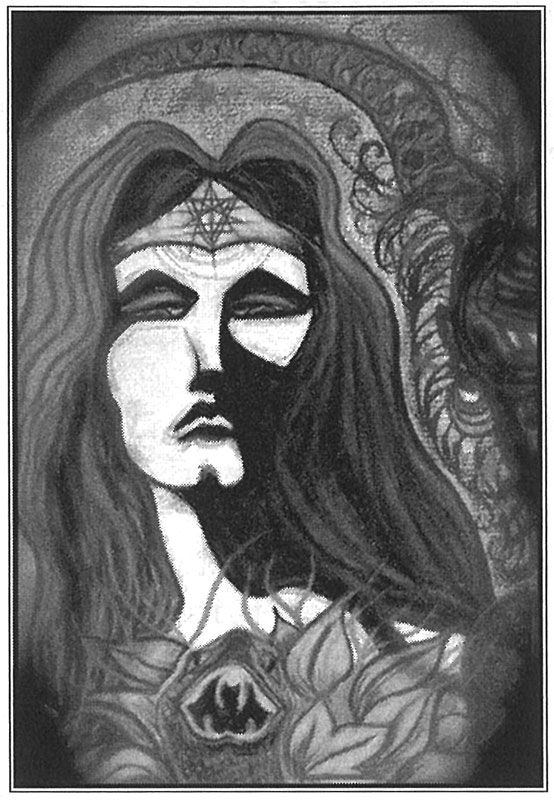

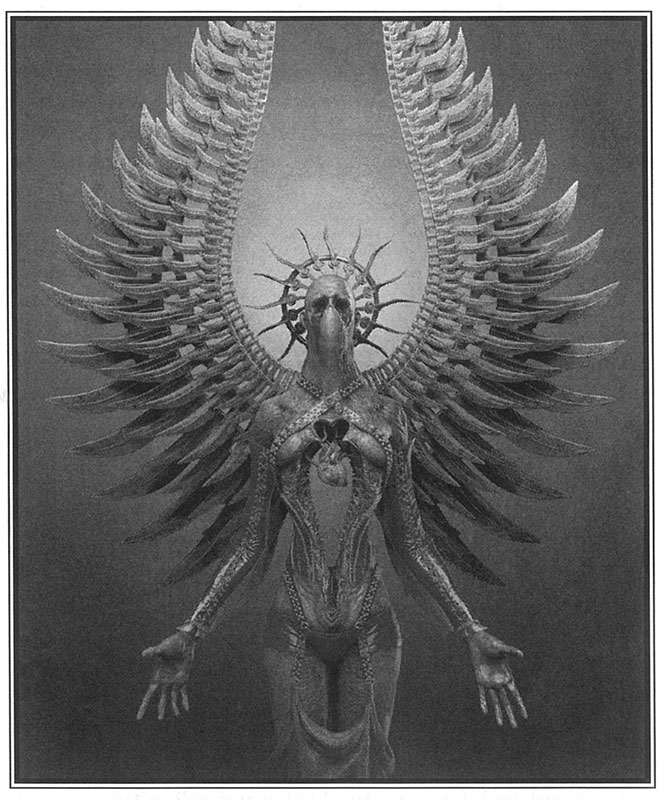

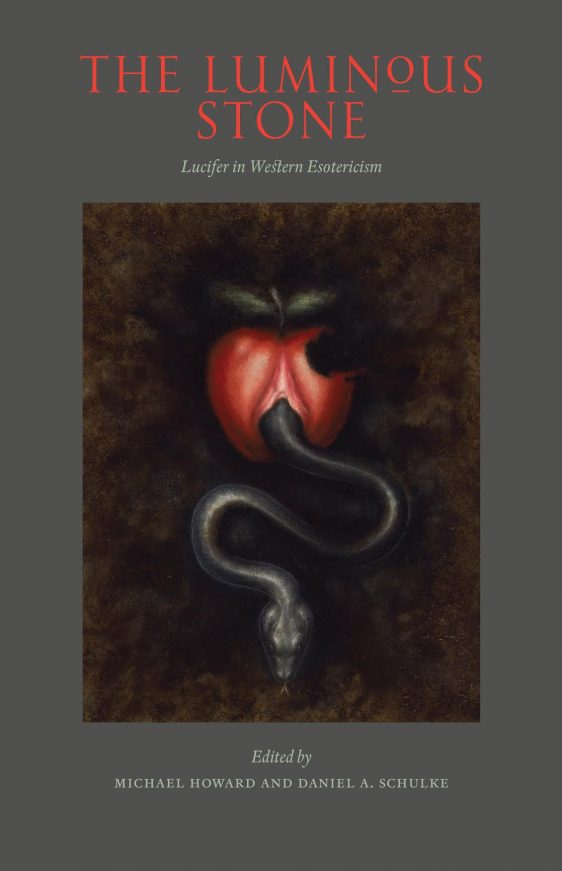

The Luminous Stone features cover art by Francisco Divine Mania (with the rather gloriously Symbolist and Decadent-styled Garden), while the interior is punctuated occasionally with the black and white silhouetted images of Hagen von Tulien. It’s not always clear if von Tulien’s images relate to the essays that precede or proceed them, but they are as striking as ever. I’m particularly partial to the one that looks like an airline safety card, in which the hazard appears to be a sorcerous attack; the only option seems to be to panic.

Overall, The Luminous Stone is an enjoyable volume, if a little underwhelming. Its 150 pages fly by, and while there are some very good contributions, there’s less of a sense of this being as essential a read as, say, Hands of Apostasy was. There’s a few glaring spelling and formatting errors that are somewhat unexpected due to the usually high standards of Three Hands Press. Raven Grimassi’s piece is particularly prone to this, referring to ‘Gain Mysteries’ when surely ‘Grain’ is intended, and having St. Jerome miraculously turn into St. James between paragraphs. He’s not alone though, and in another essay, an explanatory note is incorporated, italic styling and all, into the Robbie Burns poem it is commenting upon. The best of these errata, due to its surreal qualities, is in Lee Morgan’s piece The Lucifer Moment, where he notes that the ubiquitous image of the Luciferic anti-hero means we are ready to see Lucifer in a new way “very shorty” …which certainly would be a startling new look for the Light Bearer; and indeed, one could argue that an encounter with a diminutive fallen angel would create that paradigm-shifting moment of Morgan’s title.

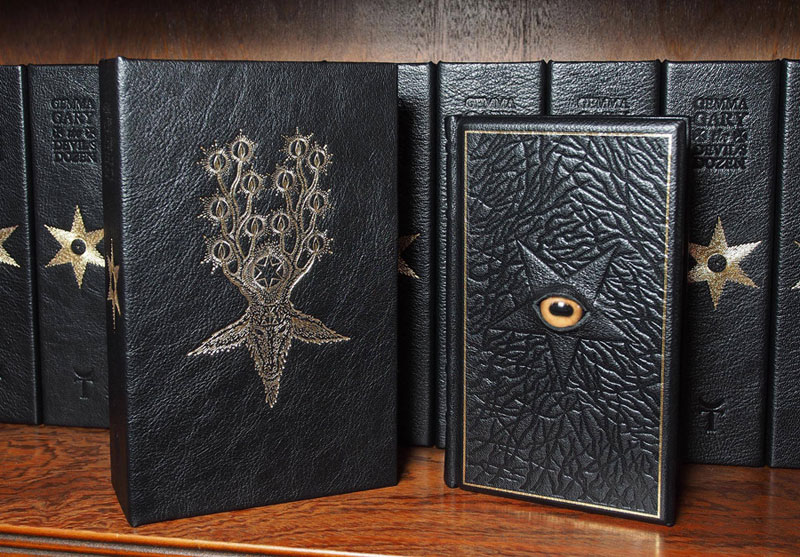

The Luminous Stone is available in a total run of 3049 copies: 2000 as a trade paperback, as well as a hardcover edition of 1000 copies bound in green cloth with colour dust jackets, and a deluxe edition of 49 copies quarter-bound in goat leather with hand-marbled endpapers. The paperback version, conveniently available via Amazon, features a stiff, weighty card for the cover and reverse, making for a tight binding that requires a little more effort than usual to keep the book open.

Published by Three Hands Press