Of late, Inner Traditions have released several books by Stephen Flowers in which older titles, previously published in small runs by his Rûna Raven Press, have been reworked into more complete versions. It comes as a mild surprise, then, to find that with the exception of pages 52-83 (published by Rûna Raven in 1998 as Johannes Bureus and Aldalruna), this book is an almost entirely new work. That is not to say that it necessarily covers ground unfamiliar to anyone that has followed Flowers’ oeuvre over the years, as the reader will encounter faces familiar, especially if you have read any of his books on the German runic renaissance or Nazi occultism. Like his 2017 work, The Northern Dawn, this book constitutes a part of a trilogy, though just to be difficult, it’s a different trilogy to that one, with Revival of the Runes being part two in an unnamed series focusing on the history of the Rune Gild. The first volume remains to be published, but confusingly, the series has already concluded with its final volume, the previously reviewed History of the Rune-Gild, which was written, just to be difficult again, by Flowers under his pen name of Edred Thorsson, and published not by Inner Traditions but by the Gilded Books imprint of Arcana Europa Media.

Of late, Inner Traditions have released several books by Stephen Flowers in which older titles, previously published in small runs by his Rûna Raven Press, have been reworked into more complete versions. It comes as a mild surprise, then, to find that with the exception of pages 52-83 (published by Rûna Raven in 1998 as Johannes Bureus and Aldalruna), this book is an almost entirely new work. That is not to say that it necessarily covers ground unfamiliar to anyone that has followed Flowers’ oeuvre over the years, as the reader will encounter faces familiar, especially if you have read any of his books on the German runic renaissance or Nazi occultism. Like his 2017 work, The Northern Dawn, this book constitutes a part of a trilogy, though just to be difficult, it’s a different trilogy to that one, with Revival of the Runes being part two in an unnamed series focusing on the history of the Rune Gild. The first volume remains to be published, but confusingly, the series has already concluded with its final volume, the previously reviewed History of the Rune-Gild, which was written, just to be difficult again, by Flowers under his pen name of Edred Thorsson, and published not by Inner Traditions but by the Gilded Books imprint of Arcana Europa Media.

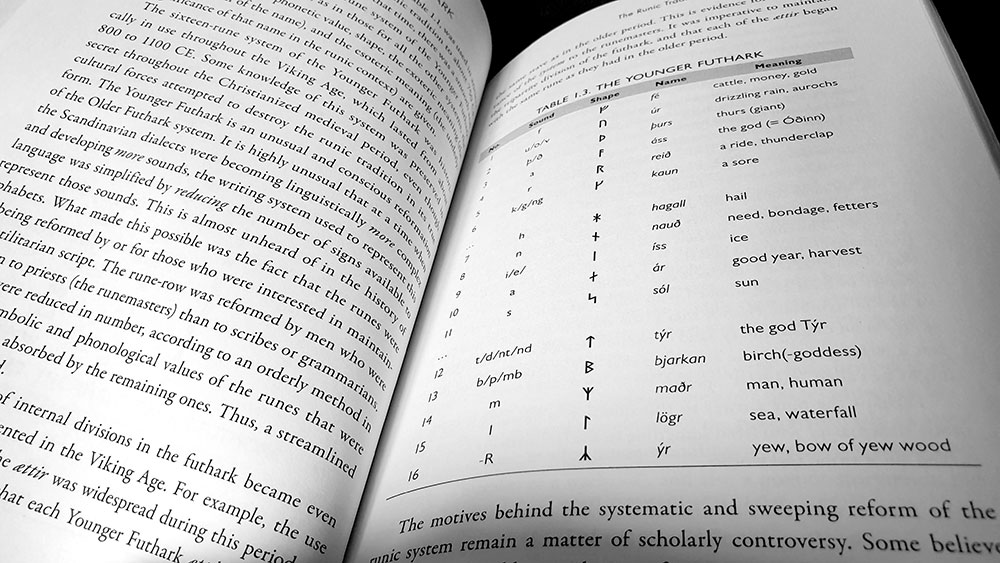

Subtitled The Modern Rediscovery and Reinvention of the Germanic Runes, Revival of the Runes traces said revival from the Swedish scholars of the 1500s and 1600s, into the Enlightenment, flowing into the Romanticism of the 1800s and then into the Germany explorations of runic mysticism both before and during the Third Reich. Flowers assumes little of his readers, and any prior knowledge they might have, and begins not with this modern rediscovery, but with a fairly thorough historical primer on the runes, covering off both elder and younger futharks as well as the Anglo-Frisian, with a particular focus on examples of inscriptions and their esoteric implications.

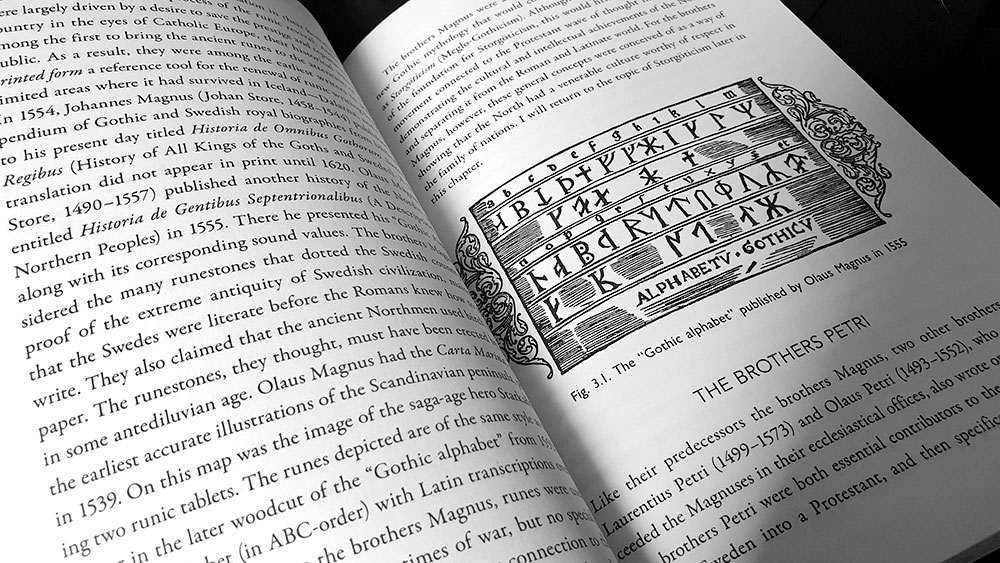

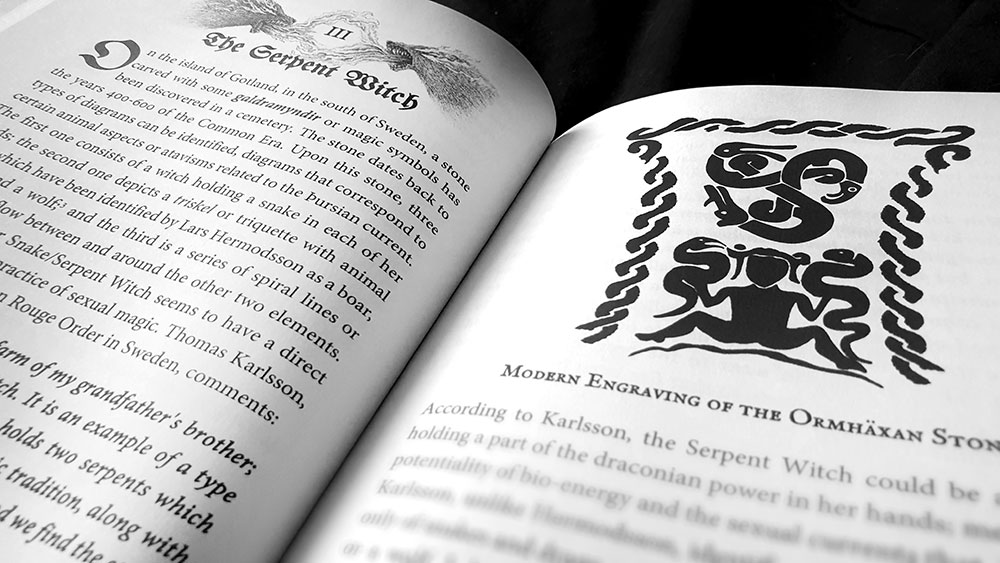

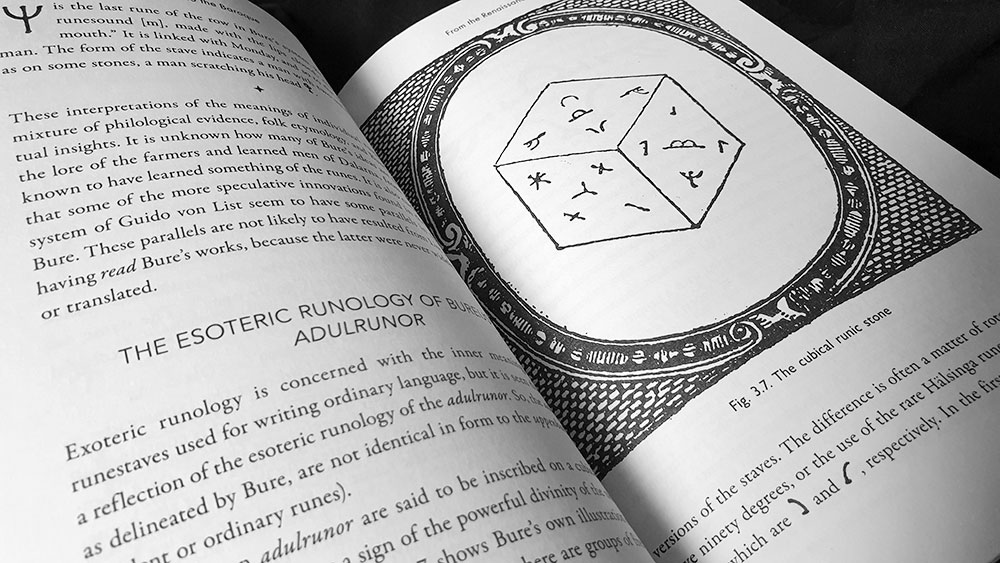

Thus, it is 43 pages in before we get to the first modern period of this history, what Flowers defines as the revival phase spanning from the Renaissance to the Baroque over the two centuries from 1500 to 1700. Flowers begins with the brothers Magnus, Johannes and Olaus, continues into another set of Swedish brothers, Laurentius and Olaus Petri, before considering Johannes Bure, Olof Rudbeck and the one exception in this almost-all-Swedish line-up, the Danish Olaus Wormius. As with many of the figures discussed in this book, each person receives a fairly brief biography, running to a couple of pages at most, and as little as two thirds of a page. The one disproportionate exception is Johannes Bure, since Flowers’ aforementioned Johannes Bureus and Aldalruna from 1998 has done all the work, and so, instead of a couple of paragraphs, Bure gets a hefty 32 pages on both his life and his adulrunor system. Of course, this emphasis is fitting, given the importance of Bure in the emergence of both runic esotericism and its exoteric grounding, with adulrunor embodying a complex cosmology and interpretation of the runes that recalls the types of idiosyncratic and often Judaeo-Christian-tinged systems that German runologists like Guido von List, Karl Maria Wiligut and Siegfried Kummer would develop centuries later. Flowers’ consideration of Bure is aided in addendums by the work of Thomas Karlsson, whose The Adulruna and the Gothic Cabbala (published separately in only Swedish, German and Italian, and then as part of Nightside of the Runes) is acknowledged here as the most extensive English work to date on Bure.

Thus, it is 43 pages in before we get to the first modern period of this history, what Flowers defines as the revival phase spanning from the Renaissance to the Baroque over the two centuries from 1500 to 1700. Flowers begins with the brothers Magnus, Johannes and Olaus, continues into another set of Swedish brothers, Laurentius and Olaus Petri, before considering Johannes Bure, Olof Rudbeck and the one exception in this almost-all-Swedish line-up, the Danish Olaus Wormius. As with many of the figures discussed in this book, each person receives a fairly brief biography, running to a couple of pages at most, and as little as two thirds of a page. The one disproportionate exception is Johannes Bure, since Flowers’ aforementioned Johannes Bureus and Aldalruna from 1998 has done all the work, and so, instead of a couple of paragraphs, Bure gets a hefty 32 pages on both his life and his adulrunor system. Of course, this emphasis is fitting, given the importance of Bure in the emergence of both runic esotericism and its exoteric grounding, with adulrunor embodying a complex cosmology and interpretation of the runes that recalls the types of idiosyncratic and often Judaeo-Christian-tinged systems that German runologists like Guido von List, Karl Maria Wiligut and Siegfried Kummer would develop centuries later. Flowers’ consideration of Bure is aided in addendums by the work of Thomas Karlsson, whose The Adulruna and the Gothic Cabbala (published separately in only Swedish, German and Italian, and then as part of Nightside of the Runes) is acknowledged here as the most extensive English work to date on Bure.

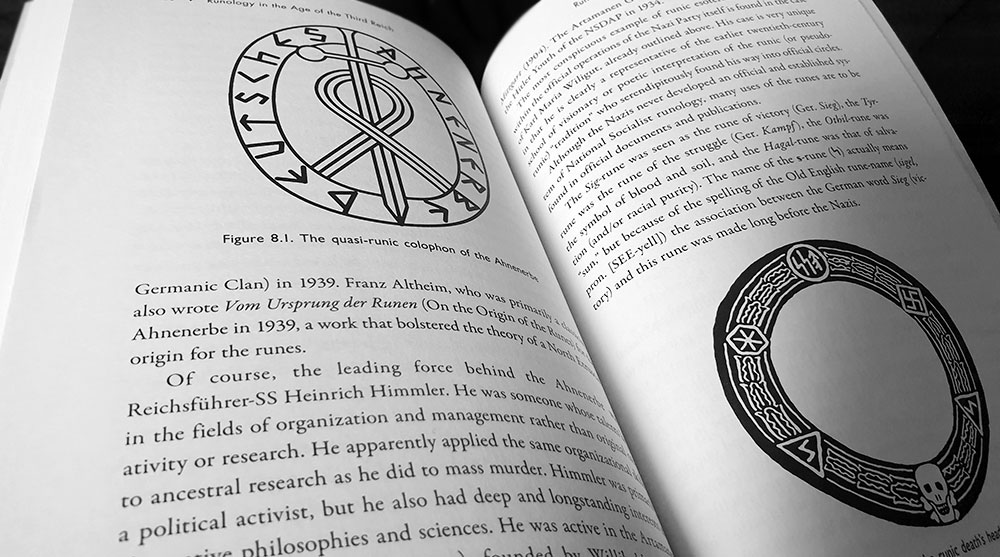

The three chapters that follow share the brevity of some of the previous biographies, with Flowers speeding through three centuries of the Enlightenment, Romanticism and nineteenth century Neo-Romanticism in a mere nineteen pages. This rather fallow time, from which only Johan Göransson warrants a separate biography, leads to the considerably more active periods of the new Germanic rebirth during the first three decades of the twentieth century, and then inevitably, runology’s evolution under and within the Third Reich. Again, things proceed at a fairly brisk pace, and this is an introduction and overview for many of these figures and movements, rather than a detailed study, for which the reader is encouraged to consult some of Flowers’ more specialised titles; a suggestion that he himself makes throughout the text. Sigurd Agrell is the only runologist to get more than a passing reference before the narrative moves on to a larger consideration of von List and his Armanen system, as well as later figures such as Kummer and Friedrich Marby. As in his other titles, Flowers’ approach to the runes in National Socialist Germany is a restrained and pragmatic one. There’s no Nazi occultists summoning unspeakable horrors from beyond the moon here, and other than a section on the SS-aligned historical think-tank known as the Ahnenerbe, the overriding message is about the Nazi use of the runes as marketing, with the esoteric aspect of a rune being more in its power as an evocatively and specifically Germanic brand, rather than something inherently magical.

Given that this revival of the runes effectively extends up into the present or at least the relatively recent, things turn somewhat autobiographical in the tenth chapter, grandly titled The Rise of Contemporary Scientific Runology and the Re-Emergence of the Rune-Gild, when Flowers documents his own part in this rebirth. For readers of his previously reviewed History of the Rune-Gild: The Reawakening of the Gild 1980-2018, or of the biography of Flowers by James Chisholm printed in Green Rûna (upon which the former is based), this will be a familiar tale. Flowers acknowledges the awkwardness of this situation, this insinuation into the narrative as he calls it, testifying that in writing this book he has attempted to remain as objective as possible, but effectively, needs now must. The retelling of his role, though, is not excessive, and is in keeping with the sparsity shown in other areas of this book, with Flowers giving a brisk history of rune publications and organisations from 1975 onwards, often shot through a biographical lens noting how he sat in relation to each of them. Despite the vaunted objectivity, there’s still a very personal angle here, with, for example, an annoyance still tangible in the travesty that Ralph Blum’s seminal (though terrible) The Book of Runes was published in 1982, beating Flowers’ Futhark to the shelves by two years. As Flowers laments, despite a version of Futhark being completed by 1979, it was then subjected to nine years of publishing purgatory from both Llewellyn and Weiser, until Weiser finally pressed print on it four years after acquiring the manuscript. Blum is not the only one to get it in the neck here, and there is the traditional Edredian airing of grievances when it comes to briefly surveying the less than stellar runic literature that emerged in the following decades. Donald Tyson (who was previously birched in Thorsson’s History of the Rune-Gild) gets it once again, while the poor, dearly departed Michael Howard receives quite the lathering and is tarred as “one of the worst offenders.”

As in the above examples, there’s always something of a distinctive Flowers tone when it comes to his books, a snarky irascible quality that makes his allegiances crystal clear, and his annoyances palpable. If he wore a bonnet, you can be sure a bee would get in there. Such is the case throughout Revival of the Runes, and it can distract to the point of tedium. Of course there’s the de rigueur moaning about ‘Marxism’ and ‘political activism’ in academia (there has to be at least one mention per title it would seem, and this one has several, with the reader looking wearily to the horizon as every now and then a little gripe about the state of the academy inevitably heaves into view). But beyond that almost expected angry-uncle-at-Thanksgiving invective, there are other strange little get-off-my-lawn moments, like when, as an abrupt contemporary analogy, he categorically states that “IT guys” (his air quotes) apparently “keep things complex and ever-changing” solely to ensure future employment. Oh, so that’s how technology and expertise works, the inexorable march of progress is just there to keep the plebs one step behind. Those sneaky IT guys, what will they think of next? 6G? A flying car just when I’ve got the hang of these wheel things? Methinks at some point there must have been a particularly gruelling morning with technical support on call trying to get the dialup working at the hof. One’s mileage will vary as to how much this tone detracts, or adds, to the overarching narrative. If nothing else, it makes Flowers’ writing style distinctive and idiosyncratic; much like the equally arch tone of this reviewer, oh snap.

Revival of the Runes concludes with Flowers’ vision of an ‘integral runology for the future,’ a largely Edredian philosophical musing, followed by two appendices. The first is a chronology of the runic revival, beginning in 1554 with the posthumous publication of Historia de Omnibus Gothorum Sueonumque regibus by Johannes Magnus, and ending in 2010 with the creation of the Futhark: International Journal of Runic Studies. The second appendix is a reprint of a brief article from 1986 on the claimed runic origins of the peace symbol in which the Elhaz rune is imagined to have been inverted and placed in a circle; an idea that carries as much weight as the satanic panic idea that it was an inverted and broken cross. This is a strange inclusion not just because of how inexplicably incongruous the article’s placement is, but also because this speculation has been long debunked, given that the creation of the nuclear disarmament symbol by designer Gerald Holtom is well attested, as is its incorporation of the semaphore representation of the letters N and D.

Revival of the Runes concludes with Flowers’ vision of an ‘integral runology for the future,’ a largely Edredian philosophical musing, followed by two appendices. The first is a chronology of the runic revival, beginning in 1554 with the posthumous publication of Historia de Omnibus Gothorum Sueonumque regibus by Johannes Magnus, and ending in 2010 with the creation of the Futhark: International Journal of Runic Studies. The second appendix is a reprint of a brief article from 1986 on the claimed runic origins of the peace symbol in which the Elhaz rune is imagined to have been inverted and placed in a circle; an idea that carries as much weight as the satanic panic idea that it was an inverted and broken cross. This is a strange inclusion not just because of how inexplicably incongruous the article’s placement is, but also because this speculation has been long debunked, given that the creation of the nuclear disarmament symbol by designer Gerald Holtom is well attested, as is its incorporation of the semaphore representation of the letters N and D.

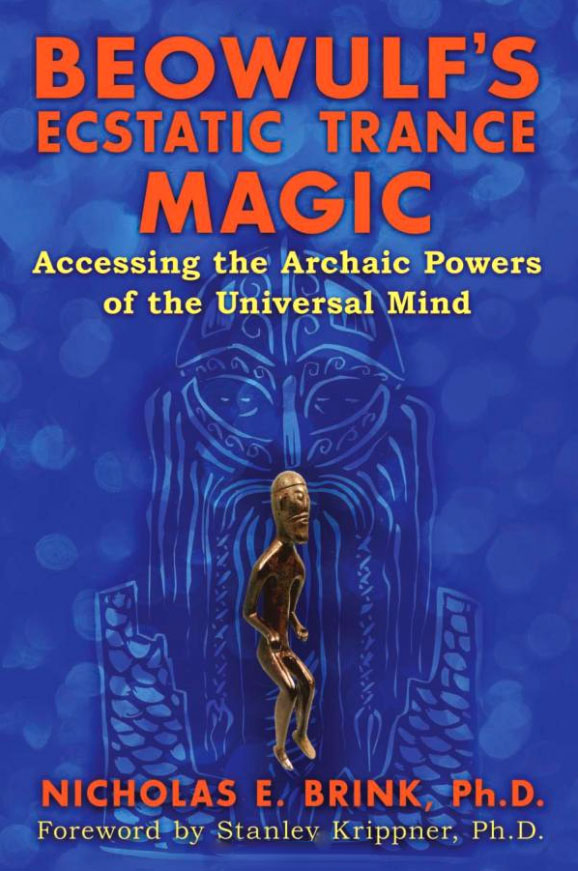

Revival of the Runes is very much a trade paperback, rather than a thesis, an overview with subjects covered briefly (save for the blessed Johannes Bure), and in which, despite a ten page bibliography, the only actually works cited within the text are almost entirely those of Flowers himself. It has been formatted with text and layout design by Virginia Scott Bowman, using Garamond for body, along with Gill Sans and Futura as contrasting san serif headers and sub headers. The rather fetching Highstories is used for chapter headings and as the cover face, where it sits next to a low-opacity version of the Ahnenerbe’s emblem, which is an, um, interesting choice of symbols to lead with there, Inner Traditions, but you do you. Less problematic is the choice of a lovely hero image, with the cover using one of the image panels from the Golden Horns of Gallehus; although considering the book’s modern subject, the fifth-century date of the Gallehus horns peculiarly makes the Ahnenerbe emblem the more relevant of the two images.

Published by Inner Traditions