Scarlet Imprint describes Peter Grey’s Apocalyptic Witchcraft as “neither a how-to book, nor a history, rather it is a magical vision of the Art in its entirety.” While it may not be a history in the Edward Gibbon sense, there are certainly historical threads the run throughout this work, woven together with others of equal parts philosophy, polemic and prose. Early in the piece, Grey notes that while he is informed by academia, he is not intending to write an academic text; and as a result, references are not cited in text but listed as a general reading list for each chapter. Instead, he takes a cue from Robert Graves in seeing poetry and fiction as a profound expression of the mysteries of the goddess, with the work of various writers providing a lens through which she can be revealed. And so, the names Ted Hughes, Peter Redgrove and Penelope Shuttle, and indeed, Graves himself, appear as frequent touchstones throughout this work. For Grey, Redgrove and Shuttle managed to tap into the essence of witchcraft: in particular a focus on menstruation and the use of dreams for magickal exploration. Hughes, in turn, celebrated the devil in the devi, the visceral qualities of the goddess of witchcraft who is nature personified in all its forms; something that Graves with his gentle, romantic sensibilities could not do.

Scarlet Imprint describes Peter Grey’s Apocalyptic Witchcraft as “neither a how-to book, nor a history, rather it is a magical vision of the Art in its entirety.” While it may not be a history in the Edward Gibbon sense, there are certainly historical threads the run throughout this work, woven together with others of equal parts philosophy, polemic and prose. Early in the piece, Grey notes that while he is informed by academia, he is not intending to write an academic text; and as a result, references are not cited in text but listed as a general reading list for each chapter. Instead, he takes a cue from Robert Graves in seeing poetry and fiction as a profound expression of the mysteries of the goddess, with the work of various writers providing a lens through which she can be revealed. And so, the names Ted Hughes, Peter Redgrove and Penelope Shuttle, and indeed, Graves himself, appear as frequent touchstones throughout this work. For Grey, Redgrove and Shuttle managed to tap into the essence of witchcraft: in particular a focus on menstruation and the use of dreams for magickal exploration. Hughes, in turn, celebrated the devil in the devi, the visceral qualities of the goddess of witchcraft who is nature personified in all its forms; something that Graves with his gentle, romantic sensibilities could not do.

Grey claims that his own voice in Apocalyptic Witchcraft is one that eschews archaic, ermine-trimmed language. Commendable sentiments, indeed, as my distain in these reviews for occultic jibba jabba will attest. Grey does do himself a disservice with this statement, though, because throughout the book he speaks with an engaging and mellifluous tone that if not ermine-trimmed is trimmed with, well, something. He archly flings words around rather beautifully and due to his enthusiasm, the writing is, fast-paced and almost, dare I say it, poetic.

Although most of the Apocalyptic Witchcraft’s content is comprised of chapters of prose that are broken up with excerpts from a poem for Inanna, the book initially takes a while to settle down, adopting numerous formats in its opening pages. It begins with an initial preamble laying out many of the core themes that are later revisited in depth, followed by a 33 point Manifesto of Apocalyptic Witchcraft, and then somewhat jarringly, a poetic travelogue called She is Without. This telling of a visit to a Mediterranean island reveals itself to be, not Shirley Valentine on Mykanos as one almost begins to expect, but rather an anti-tourist exploration of the island of Patmos, the site associated with John’s reception of the Book of Revelations. It is here, in the cave of the apocalypse, that Grey frames his own vision, a new song of an apocalyptic witchcraft that is inimically set against the 2000 year old revelation of John.

As one would perhaps expect from something that is essentially a polemic or manifesto, Apocalyptic Witchcraft is high on rhetoric but low on details. Throughout, for example, Grey makes a distinction between conventional modern pagan witchcraft (a rubric under which he includes both Wicca and Traditional Witchcraft) and his vision for an apocalyptic witchcraft. He sees elements of the former as assimilationist, whereas the latter is eternally rebellious and outside the mainstream; with witchcraft as a belief system that, he argues, has always been adversarial, standing against the clergy and the inquisitor, both medieval and modern. Quite what that means on a practical level is not explained. While there is talk of a philosophical alignment with direct action groups such as the Earth Liberation Front and the amorphous Anonymous, there is no explanation of how this could be pragmatically incorporated into witchcraft beyond unexplained metaphors of Grand Sabbats and tooth and claw.

But maybe that’s not the point, and it’s certainly not the intention, as Grey and Scarlet Imprint makes clear with their initial insistent definitions of what the book is and what it is not. Instead, Apocalyptic Witchcraft is to be read as an inspirational text. Ideas are introduced, celebrated with Grey’s often ecstatic prose, but frequently viewed from a grand distance, leaving the reader to take up the elements and run with them. This parallels Grey poetic inspirators, whose words, by their very nature, provide a vision but one that is by no means spelt out.

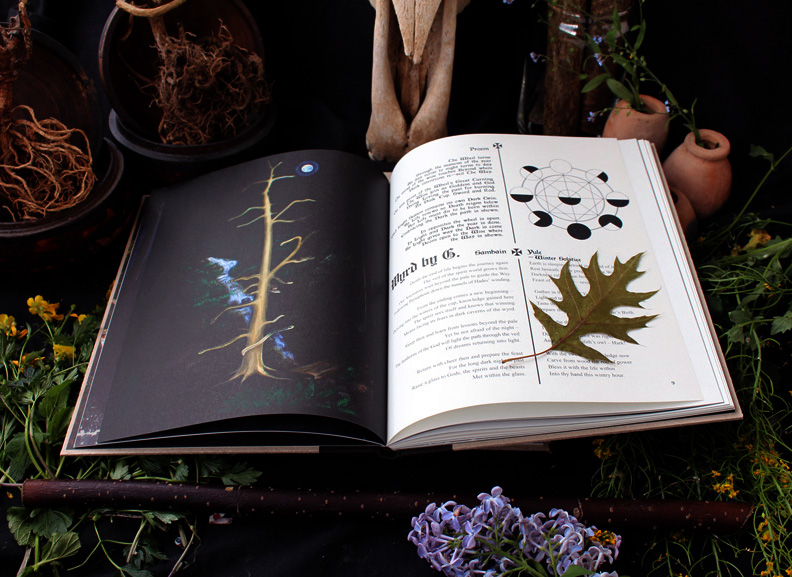

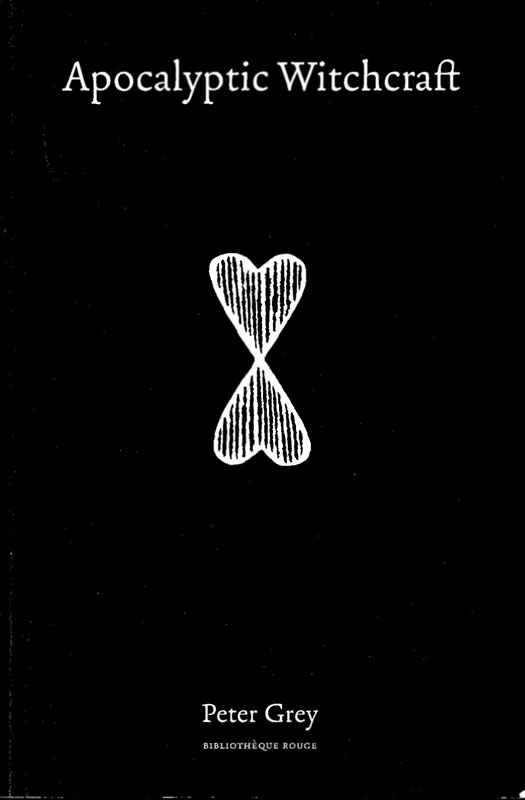

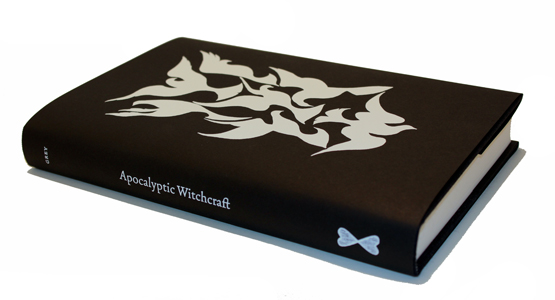

Apocalyptic Witchcraft is available in multiple versions: the Bibliothèque Rouge paperback edition, reviewed by scrooge here, with its black card binding and white ink on the cover; a now sold out Of the Crows fine edition bound in full hammered gold hand-grained morocco; and a standard hardbound Of the Doves edition bound in black linen cloth stamped with white dove devices to front and rear, embossed grey endpapers, and a dust jacket. The formatting of Apocalyptic Witchcraft is attractive and rarefied. The columns are given large 3cm margins on all sides and the type is set in a smaller than usual point size with generous, but not excessive, leading. The result, given the tall and thin columns, is an archaic quality that suits the content of the book but without any sense of it being overly telegraphed.

Published by Scarlet Imprint. ISBN 978-0-9574492-9-9