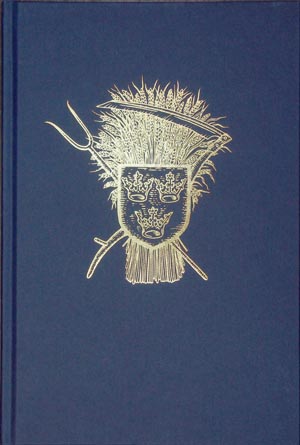

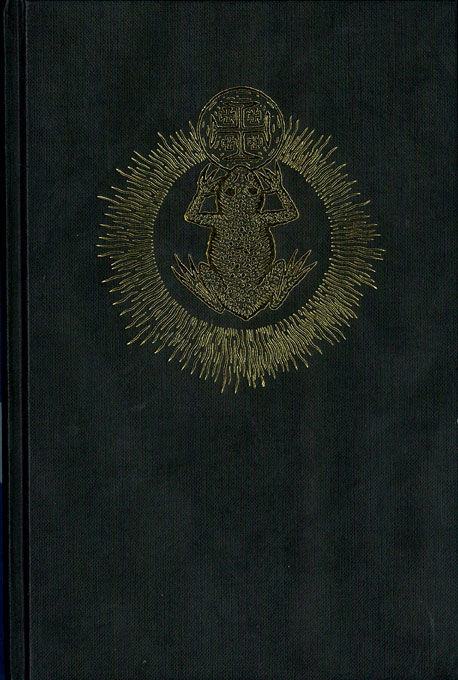

Here at Scriptus Recensera there’s no shortage of reviews of Troy Books, erm, books. This comes largely down to matters practical: they are both affordable and desirable, with even the standard editions being presented in an attractive, cloth-bound format with embossed cover designs, and beautifully formatted and illustrated within. They’re also easy to review since they are eminently readable, consistently professional and usually devoid of the kind of errors so typical of occult publishing. As such, though, when it comes time to read and review Gemma Gary’s Traditional Witchcraft: A Cornish Book of Ways, one wonders how differently this will fare amongst not just other previously reviewed Troy Books books, but also amongst Gary’s other written works.

Here at Scriptus Recensera there’s no shortage of reviews of Troy Books, erm, books. This comes largely down to matters practical: they are both affordable and desirable, with even the standard editions being presented in an attractive, cloth-bound format with embossed cover designs, and beautifully formatted and illustrated within. They’re also easy to review since they are eminently readable, consistently professional and usually devoid of the kind of errors so typical of occult publishing. As such, though, when it comes time to read and review Gemma Gary’s Traditional Witchcraft: A Cornish Book of Ways, one wonders how differently this will fare amongst not just other previously reviewed Troy Books books, but also amongst Gary’s other written works.

Traditional Witchcraft, with its somewhat generic title amongst a veritable sea of Traditional Witchcraft books, can at least make a claim to being one of the originals of the current crop, first published ten years ago in 2008, with this being the third edition from 2015, following a revised second edition in 2011. In the intervening years, Gary’s skills have grown as a writer, becoming someone who I find admirably effortless to read. This isn’t always the case here, with occasionally tortuous phrasing, peculiar usages of semicolons, and the odd run-on sentence which you can’t imagine encountering today.

Traditional Witchcraft provides something of a template to other books that have subsequently come from Gary and Troy Books. There’s an overwhelming emphasis on folklore, which is naturally for the most part specific to Cornwall. While there is a substantial bibliography at the back of the book, there is zero citing within the body, so all of this lore comes across, intentionally or not, as personal, experiential knowledge. That said, it is interesting to review the bibliography to get a sense of where things have presumably come from. It is divided into folklore and broader witchcraft sections, with the former featuring a surfeit of works from Kelvin Jones’ Oakmagic Publications, while the latter has a healthy nod to Capall Bann’s triumvirate of Jackson/Howard/Pearson.

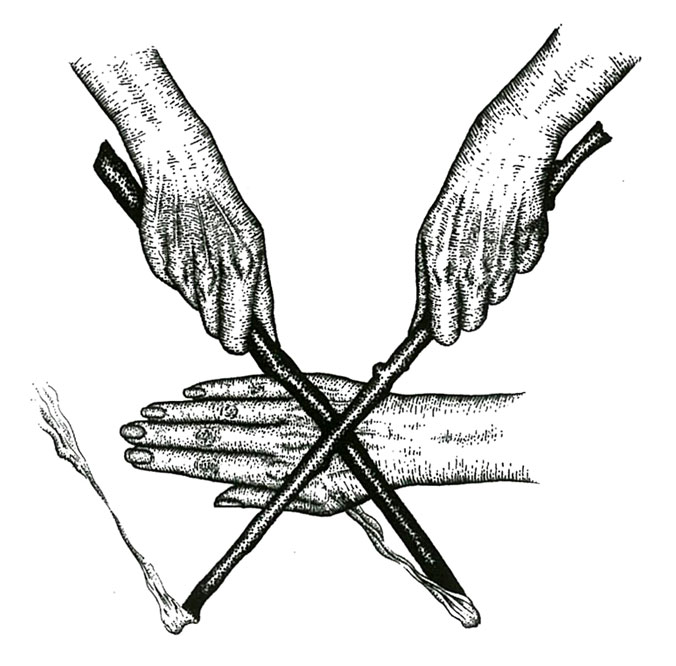

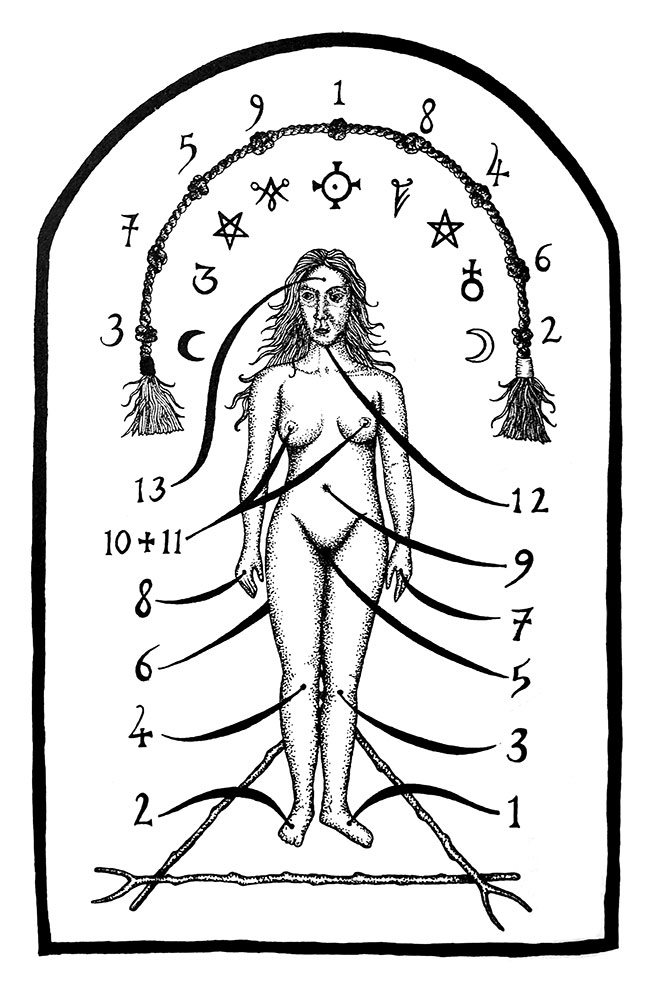

This grounding in folklore, including a welcomed consideration of the Bucca, gives way to a thorough introduction to Gary’s Cornish system of witchcraft, which takes up the rest of book’s two thirds. For anyone familiar with traditional witchcraft, there won’t be anything here that’s entirely unfamiliar or revelatory, but it is consistently given that little Cornish flavour. Gary begins by introducing the tools of cunning, at the forefront of which is the staff, which she describes as being as important to traditional witchcraft as the athame is to Wicca. This assemblage of accoutrements also includes a knife, cup, bowl, cauldron, sweeping tools, various types of stones, necklaces, and noise makers such as drums and wind roarers. Gary provides a brief description of each of these and then information on empowering them with a technique called hooding.

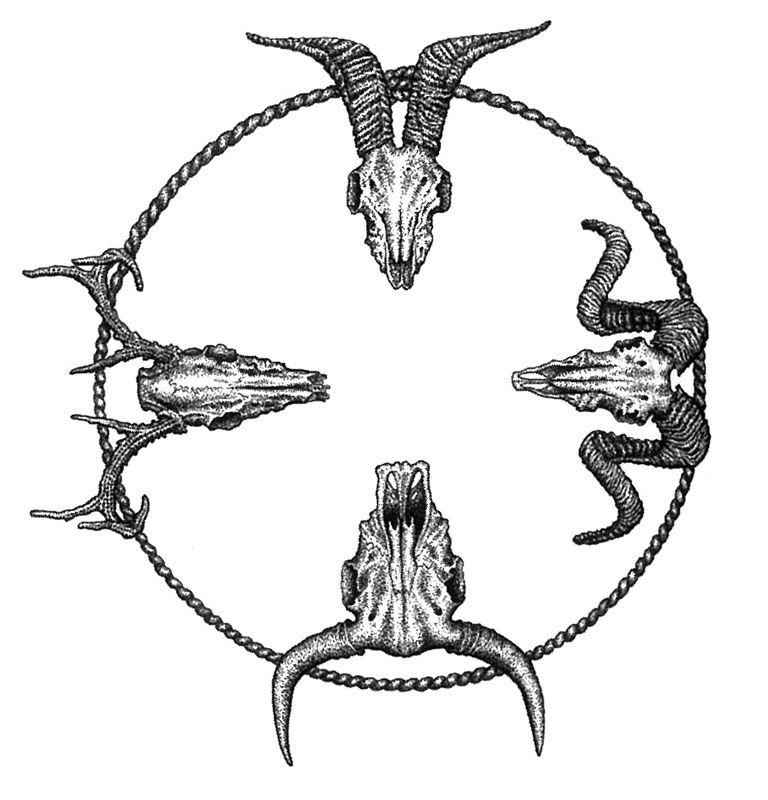

Gary then explores the cosmological setting of Cornish magic in The Witches’ Compass, using that rubric to outline a system in which the quarters are imagined as four roads emanating from the axial circle. Each road is associated with a particular form of intent, and with it a range of correspondences including seasons, elements and familiar spirits. These roads are worked with a Compass Rite in which a compass round is drawn and then walked before the specific magical act begins. Gary then provides an outline of the Troyl Hood, a procedure that is used to close any rite or workings.

With the emphasis in Traditional Witchcraft of matters folkloric, there is a significant section on witchcraft as a trade, with an exploration of charms and practical magic. This begins with a brief preamble of the types of employment a witch might find before detailing various planetary virtues and their associated powders, oils and incenses. Then follows a wide selection of charms for all kinds of sympathetic magic, the kinds of things that will be familiar from any type of folklore collection, utilising familiar simultaneously mundane and exotic ingredients like horse shoes, dead toads and knots. Gary rounds things off with what any witchcraft book needs, a survey of the ritual year, but this isn’t so much your standard Imbolcs and Beltanes, and instead have a Cornish twist, with the quartenal Furry Nights of Allantide, Candlemas, May’s Eve and Guldize being joined by the summer zenith of Golowan and the midwinter solstice of Montol. These are each presented with an explanation and then an example of a corresponding ritual. Coming to the conclusion of Traditional Witchcraft, Gary ends with a beginning and provides a chapter on initiation, with a wide ranging discussion of its history and precedents, before providing a ritual for solo initiation into her Ros an Bucca hearth.

Coming to the conclusion of Traditional Witchcraft, Gary ends with a beginning and provides a chapter on initiation, with a wide ranging discussion of its history and precedents, before providing a ritual for solo initiation into her Ros an Bucca hearth.

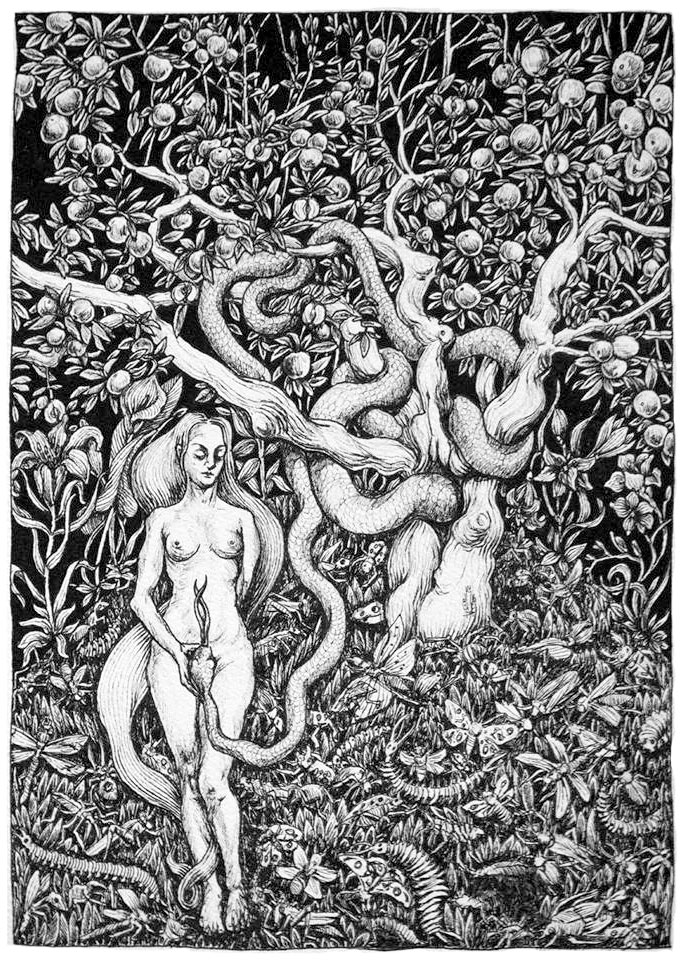

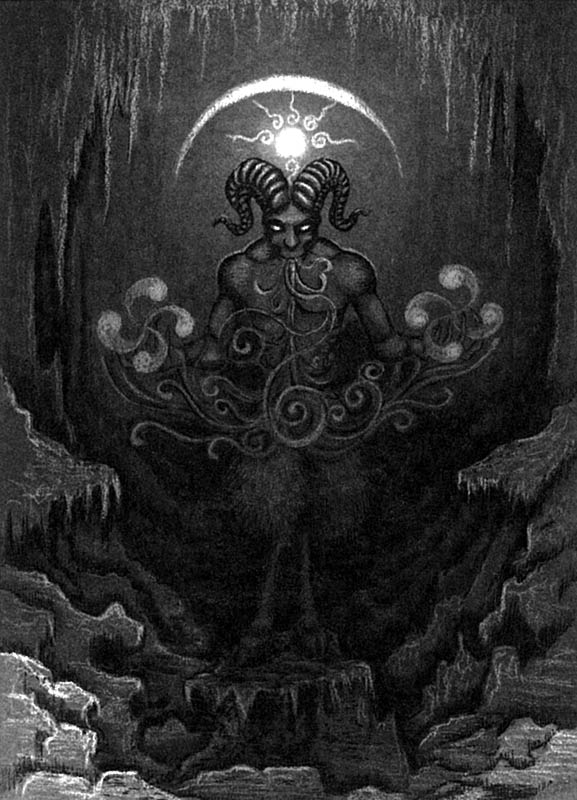

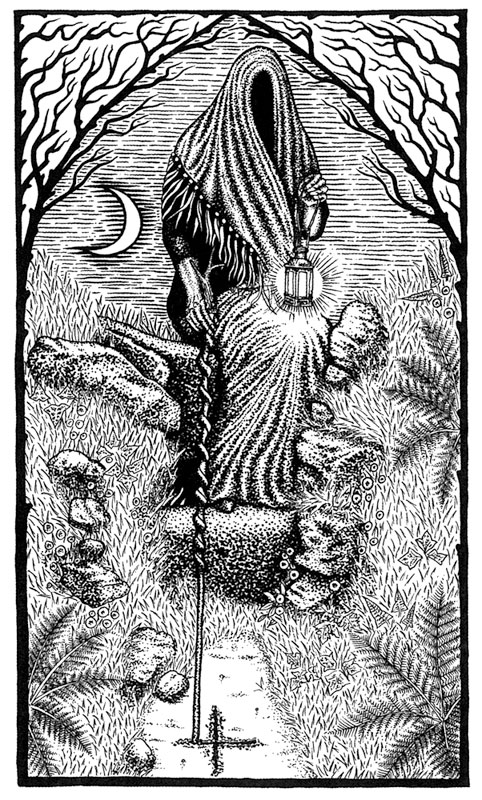

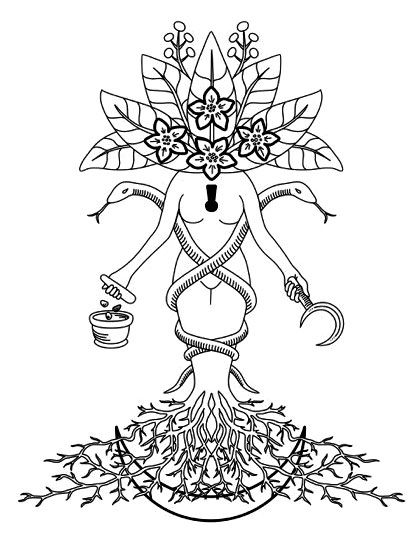

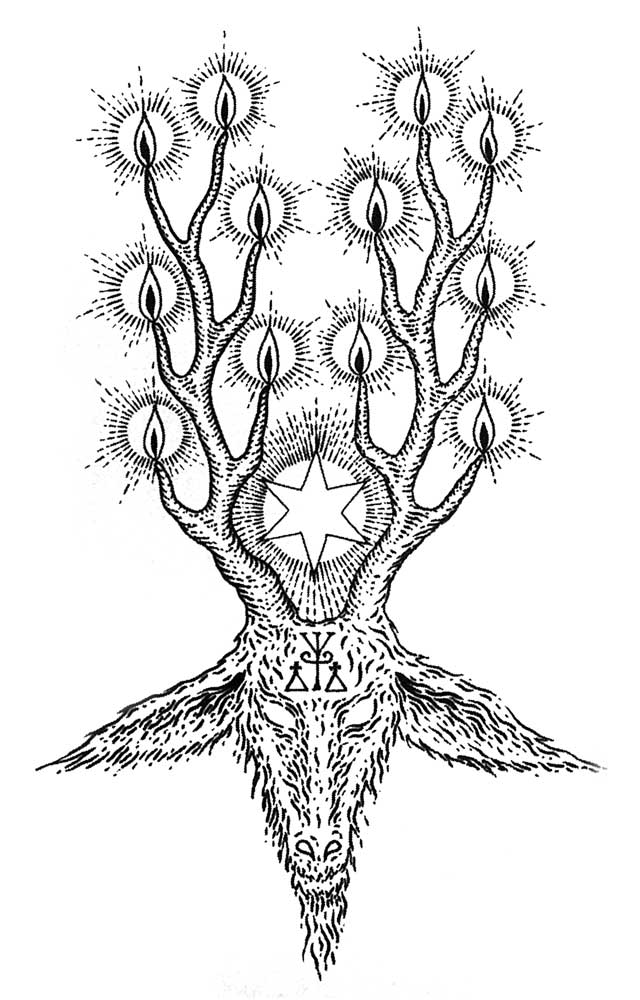

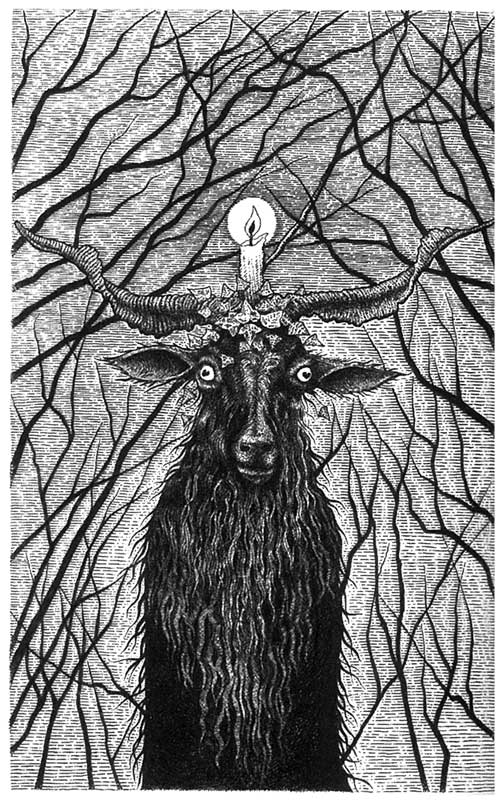

At over 200 pages, Traditional Witchcraft is a solid introduction to Gary’s oeuvre and Cornish witchcraft in particular, free of much in the way of artifice or pretension. The Bucca looms large within its pages (and on the cover of the paperback edition), while there are also tantalising mentions of Ankow, the Cornish personification of death who is here seen as a Hela-like hag of death and transformation. Interestingly, snakes also figure largely in the contents of Traditional Witchcraft, something that is perhaps not often found in similar contexts and something which adds a certain appeal for this reviewer. Gary repeatedly refers to the idea of igneus snakes as expressions of tellurian power that can be drawn up from the earth and into the body in a kundalini-like manner.

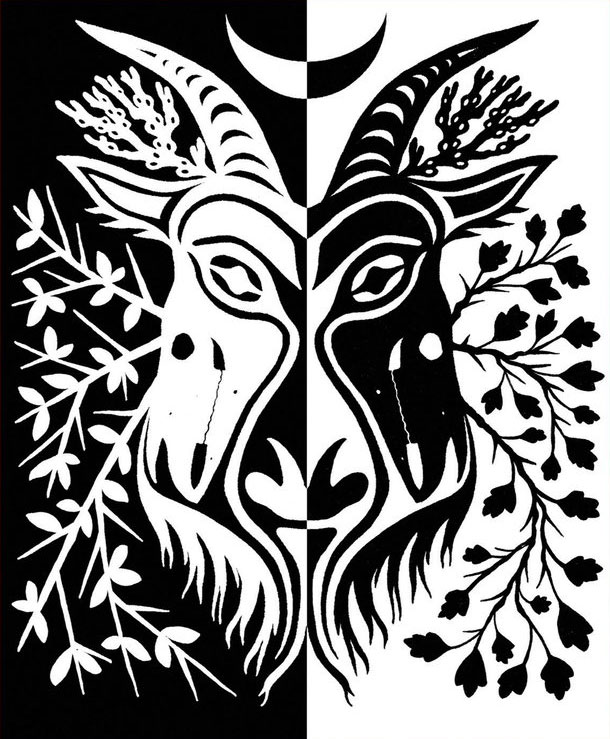

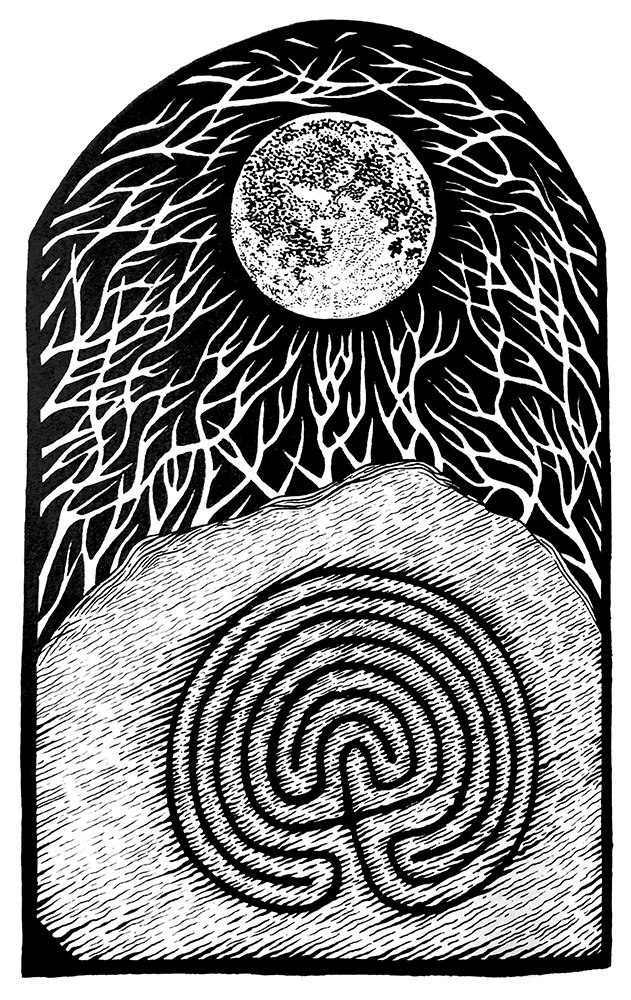

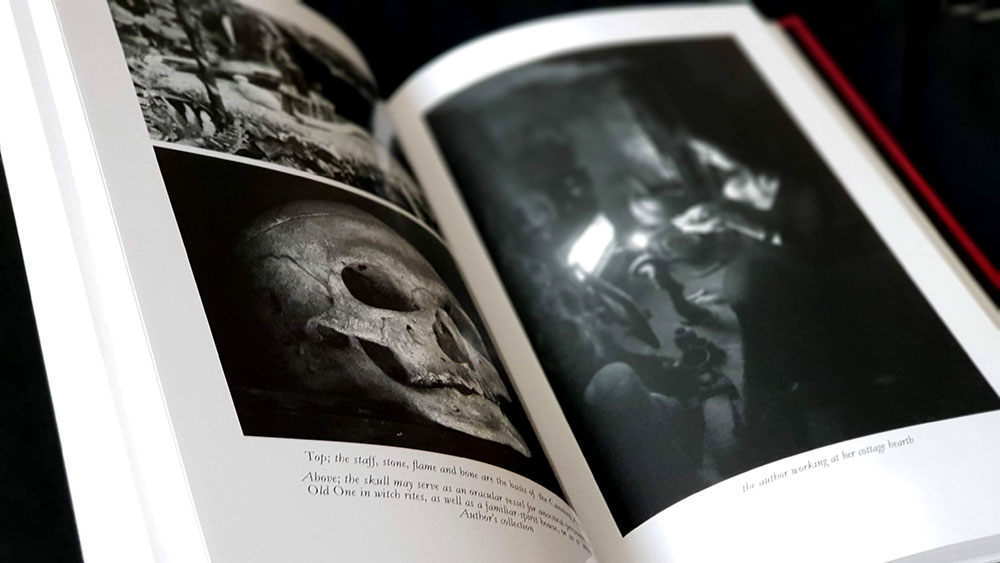

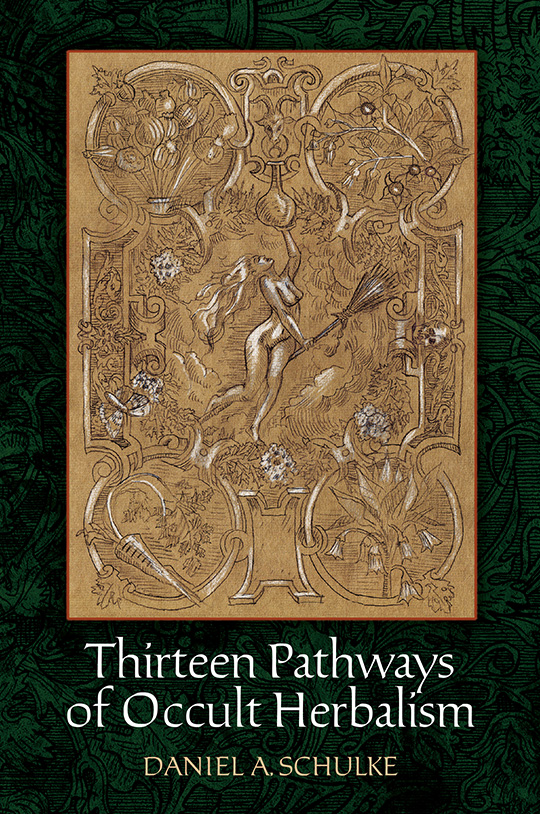

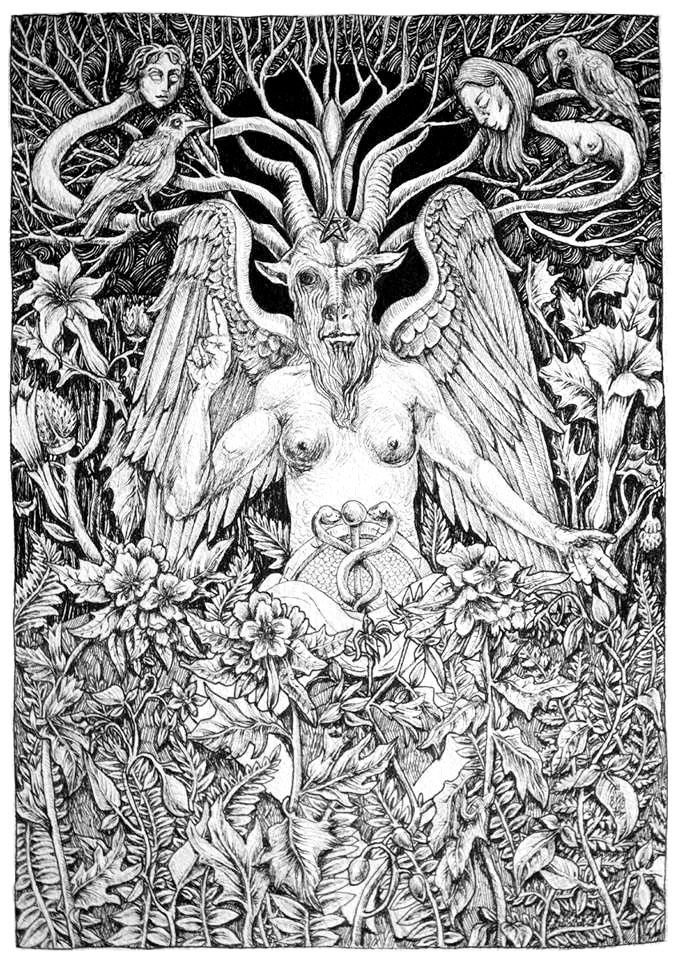

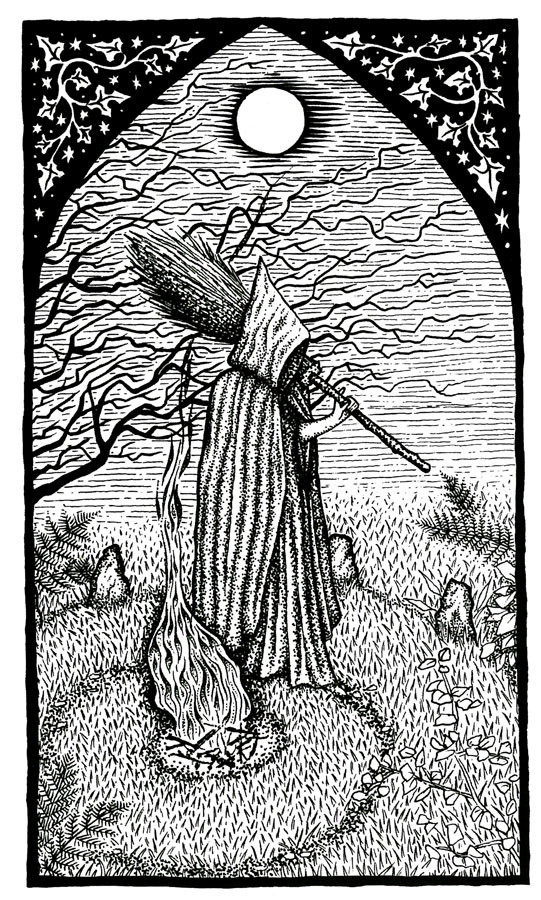

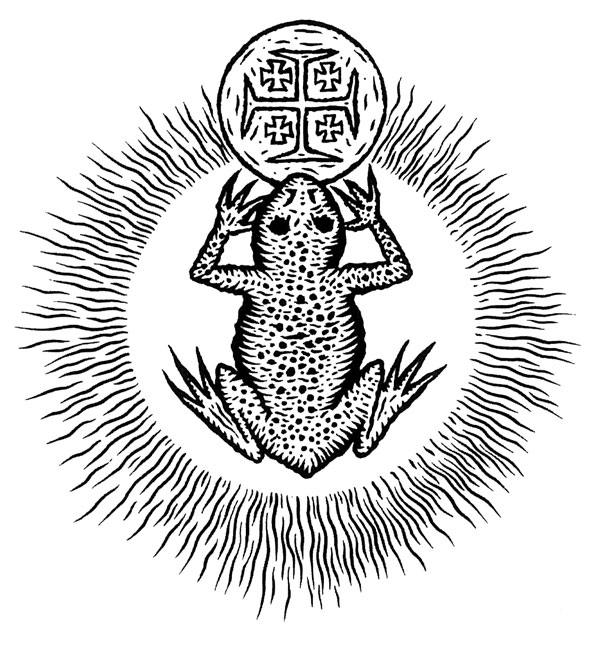

As is the Troy Books style, Traditional Witchcraft is illustrated throughout with Gary’s unmistakeable hand, though her trademark stippled stylings still seems somewhat inchoate here, and she explores a variety of other techniques; one even looking reminiscent of Daniel Schulke’s atavistic, two tone botanical considerations in Viridarium Umbris. Joining these full page and interstitial illustrations is a large collection of photographic plates by Jane Cox, either showcasing relics of note, or documenting practical acts of magic.

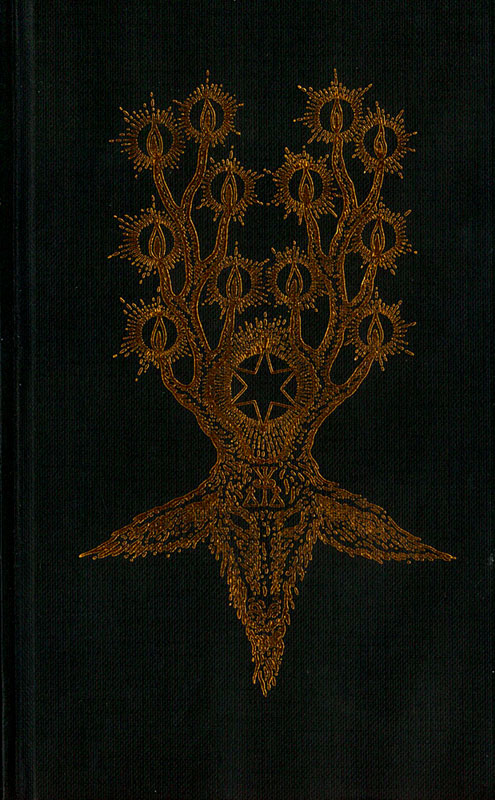

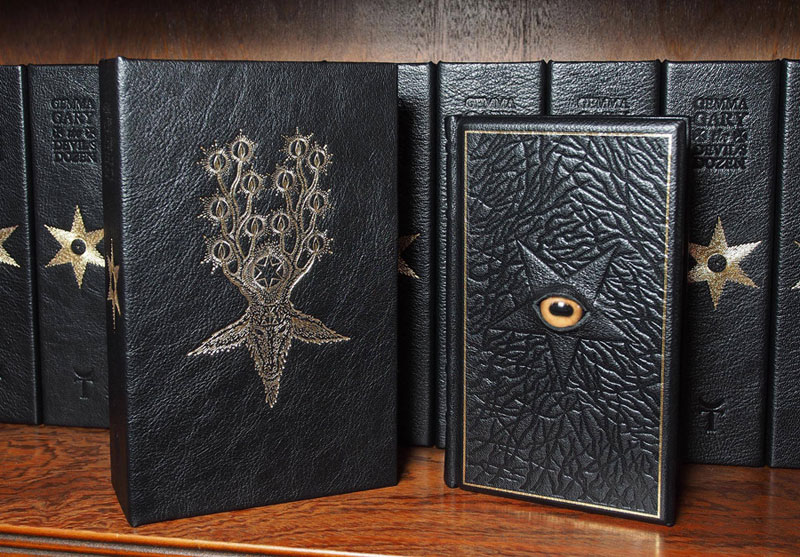

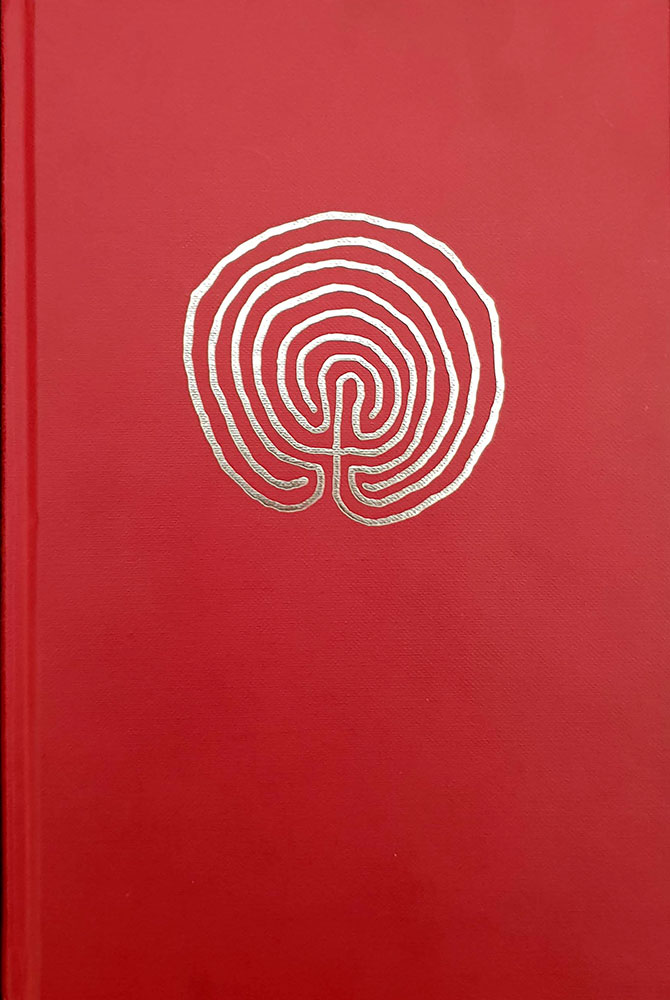

Traditional Witchcraft: A Cornish Book of Ways is available in two editions, a generic paperback version and a hardback edition. The hardback is presented in a claret red binding, with black end-papers, black and red head and tail bands and with silver foil blocking to the front and spine. In addition to these two available editions there were also a special limited edition (bound in green cloth with a unique image blocked in copper foil on the cover), a fine limited edition and a special fine edition. The fine edition, limited to 25 copies, was hand bound in scarlet hand finished goat leather with gold foil blocking to the front and spine, marbled end papers, red head and tail bands and marker ribbon, enclosed in a lined slipcase covered in red library Buckram cloth. Finally, the five exemplars of the special fine edition were hand bound in dark green fine hand polished and finished goat leather, with hand tooled raised labyrinth design on the front and gold foil blocking to the spine, with marbled end papers, capped spine ends, and gold marker ribbon, enclosed in a lined slipcase covered in green library Buckram cloth.

The title is also available as a four-CD audio book, created in conjunction with Circle of Spears Productions and read by actress and voice artiste Tracey Norman.

Published by Troy Books