Rune Games by Marijane Osborn and Stella Longland occupies a strange place in the recent history of esoteric runology. First published in 1982, it predates some of the considerably more prominent works from the likes of Stephen Flowers, Freya Aswynn, and Nigel Pennick, with Flowers’ Futhark: A Handbook of Rune Magic arriving two years later, while Aswynn’s Leaves of Yggdrasil would be first self-published in 1988. Only Ralph Blum and his mass market Book of Runes (with little rune tiles in a cloth pouch) can claim to be a contemporary, released in the same year as Rune Games, but let’s not tar the latter with the shameful brush of the former. This pedigree means that despite a metaphysical focus, there’s little in the way of references to Germanic magical groups here, and the slight bibliography naturally contains no related titles (as they didn’t exist yet, of course), with the only works directly relating to runes being academic ones: Dickins’ Runic and Heroic Poems, Elliott’s Runes: An Introduction, and Page’s An Introduction to English Runes.

Rune Games by Marijane Osborn and Stella Longland occupies a strange place in the recent history of esoteric runology. First published in 1982, it predates some of the considerably more prominent works from the likes of Stephen Flowers, Freya Aswynn, and Nigel Pennick, with Flowers’ Futhark: A Handbook of Rune Magic arriving two years later, while Aswynn’s Leaves of Yggdrasil would be first self-published in 1988. Only Ralph Blum and his mass market Book of Runes (with little rune tiles in a cloth pouch) can claim to be a contemporary, released in the same year as Rune Games, but let’s not tar the latter with the shameful brush of the former. This pedigree means that despite a metaphysical focus, there’s little in the way of references to Germanic magical groups here, and the slight bibliography naturally contains no related titles (as they didn’t exist yet, of course), with the only works directly relating to runes being academic ones: Dickins’ Runic and Heroic Poems, Elliott’s Runes: An Introduction, and Page’s An Introduction to English Runes.

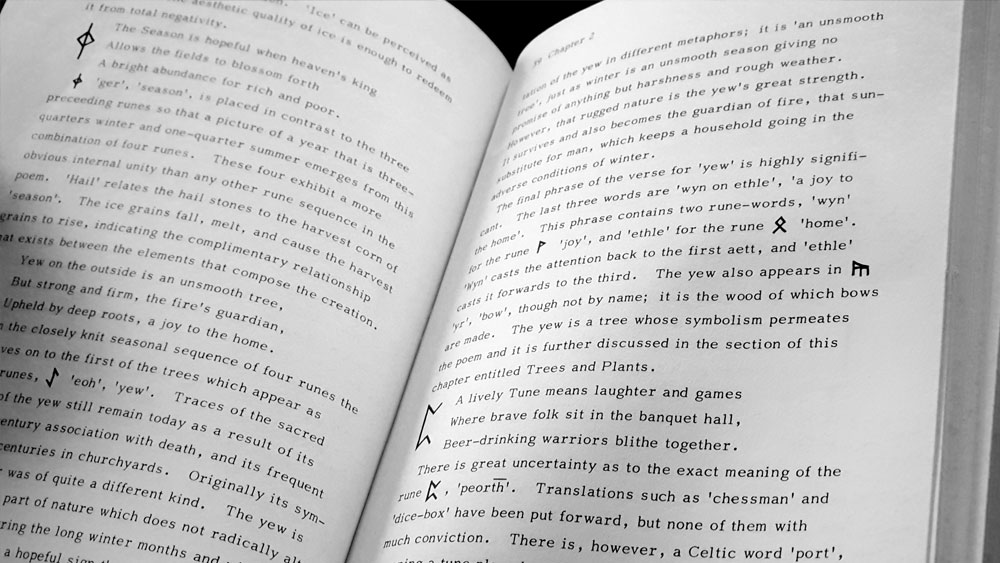

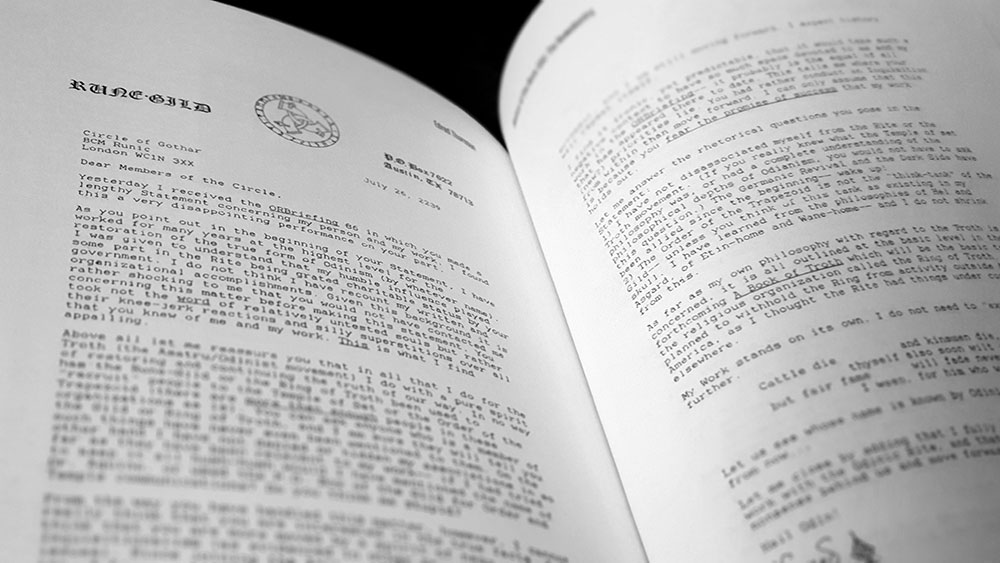

Perhaps highlighting the hoary antiquity of this book, Rune Games is formatted in a monotype face that may have been come from a then-state-of-the-art word processor, but which carries with it a hint of a far older typewriter. There don’t appear to have been any special characters on this word processor, so the thorn and eth letters are both transliterated to ‘th’, with ‘eth’ differentiated in its appearances with a line above the ‘th.’ It’s almost cute but disorientating for those with the luxury of always reading the text with special characters baked in. As one would expect, there were also no runic characters on this ancient device, so when needed, these have been charmingly hand-drawn into the body copy. Double cute.

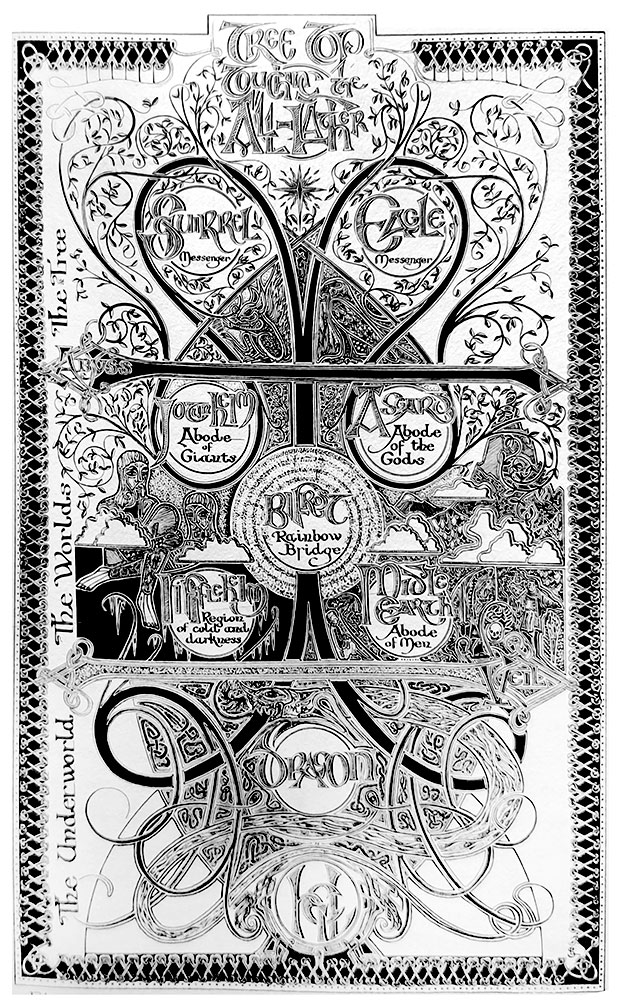

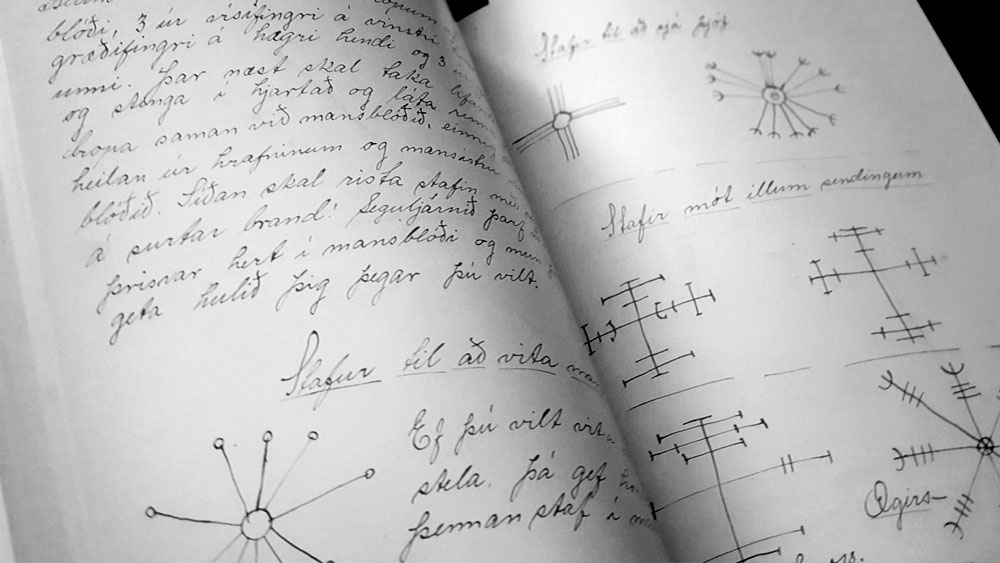

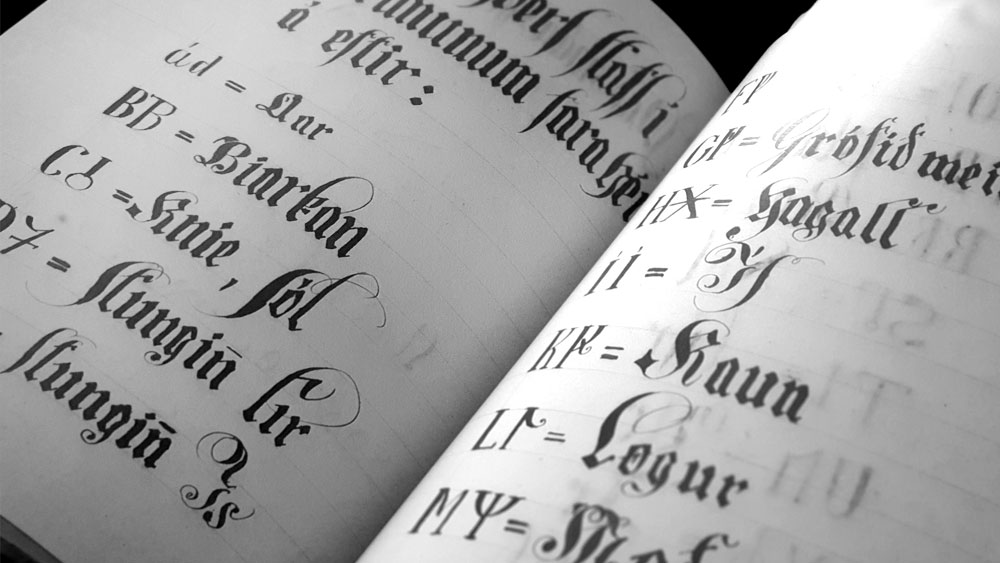

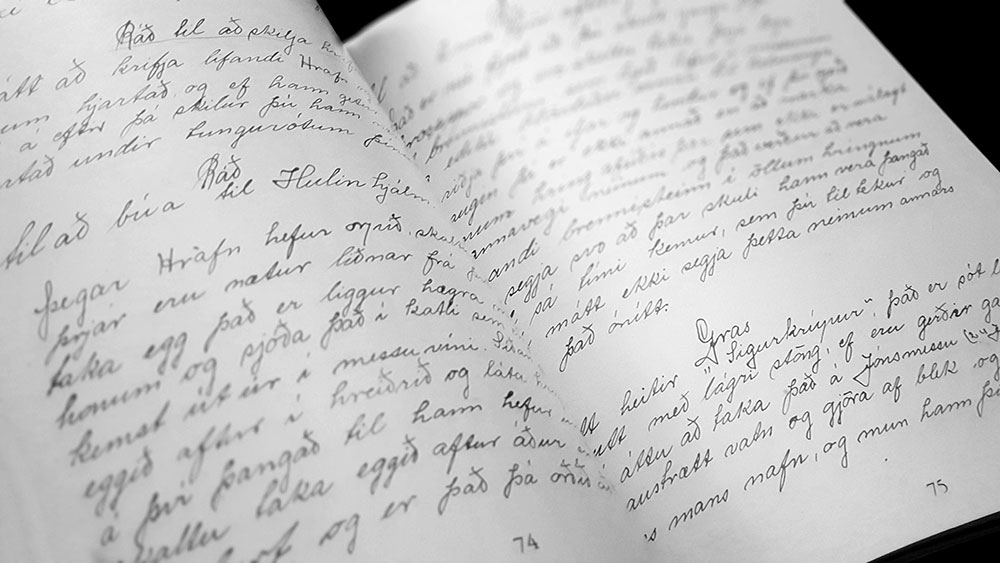

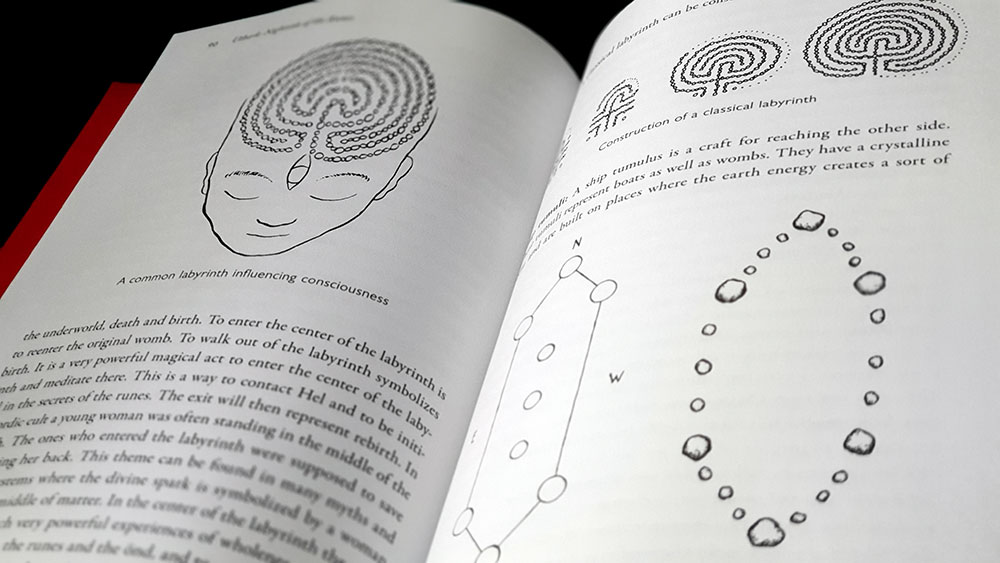

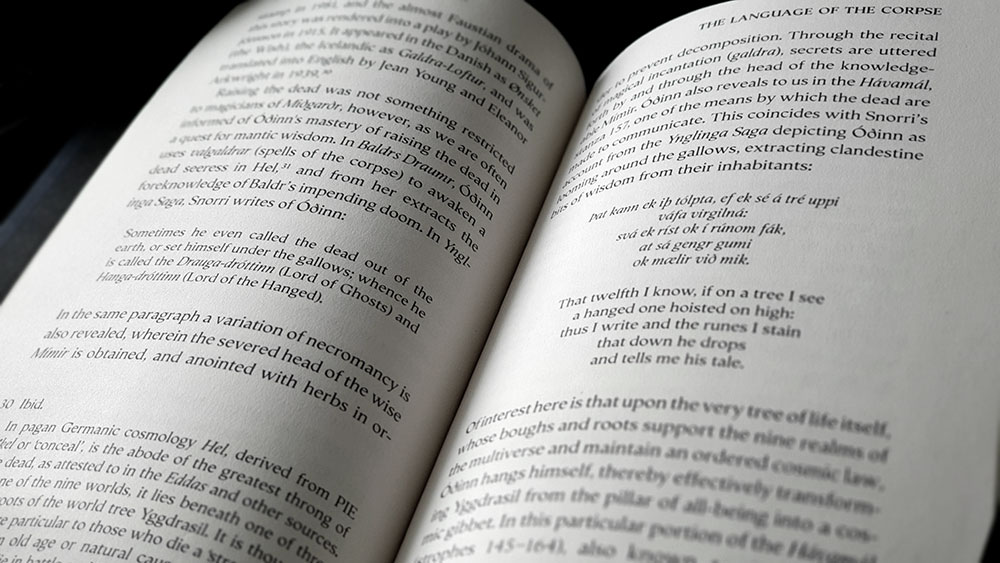

One of the most appealing aspects of Rune Games is an aesthetic one, with the peppering throughout of ink illustrations by Steven Longland. In contradistinction to the conventions of runic and Viking art that has come to dominate this field (as featured in the incessant sponsored posts on my Instagram feed), Longland has a calligrapher’s hand, drawing on the illuminated manuscript style of the Book of Kells to create something that looks more Celtic than obviously Germanic. Indeed, the Book of Kells plays a surprising and disproportionate role in this work, but more about that later.

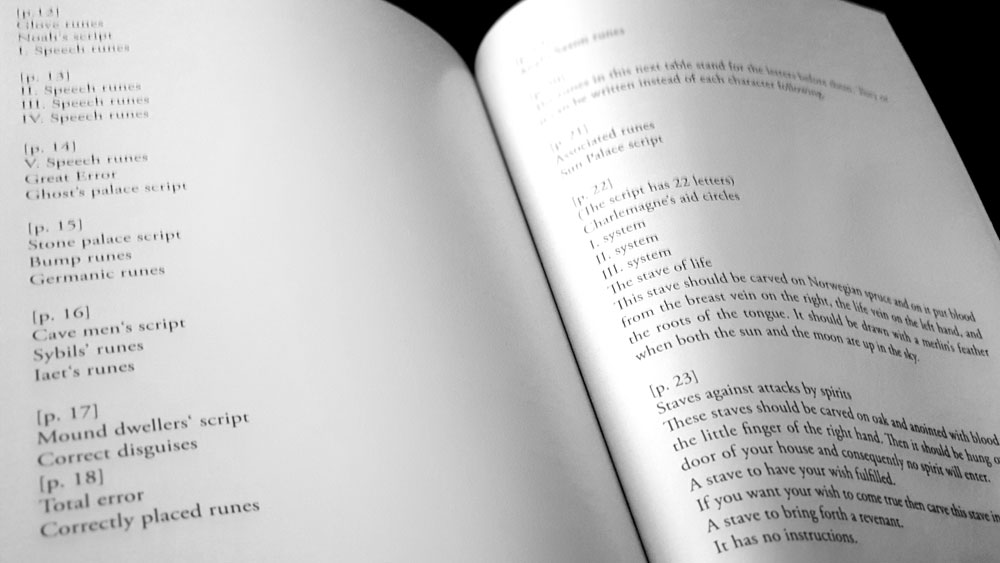

While later titles from the milieu of esoteric runology would tend to focus on the 24 runes of the Elder Futhark, Osborn and Longland explore the larger Ango-Saxon version; a natural choice since the accompanying Anglo-Saxon Rune Poem provides the most complete information on the meaning of each rune, cryptic though some of them be; with the poem’s Icelandic and Norwegian counterparts detailing only the sixteen runes of the shorter Younger Futhark. After a brief introduction to the runes in general, Osborn and Longland follow the familiar pattern of books such as these by detailing the meaning of each rune, beginning with a translation of the appropriate verse from the Anglo-Saxon Rune Poem before providing an investigation of symbolism that usually runs up to a page and a half for longer entries, and as little as half a page for others. The authors draw fairly purely and pragmatically from etymology and the information found in the rune poems, with little in the way of outlandish or metaphysical speculation.

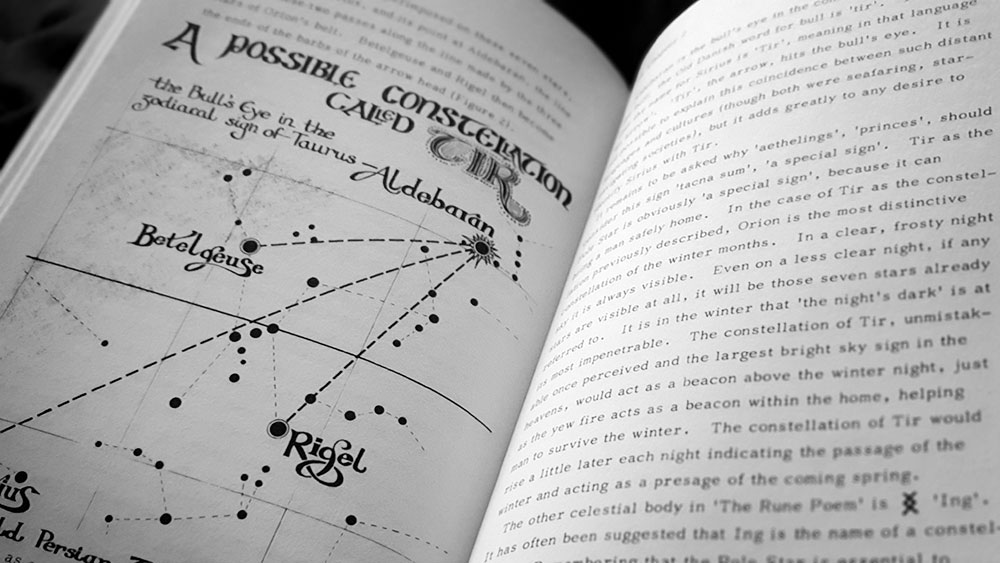

There is a concerted effort to show patterns within the runes, creating a thematic image that emphasises, as the rune poem naturally does, Anglo-Saxon ideas of home, hall and hearth. This reaches its zenith in an additional section where Osborn and Longland return to some of the runes by grouping them via their shapes as well as their association with animals, trees and plants, and the stars. The latter provides one of the notable innovative thoughts within the book, not seen anywhere else that I recall, with an interpretation of the Tir rune (described in the poem as a special astral sign, ever on course at night) as an arrow-shaped constellation comprised of the stars Sirius, Aldebaran, Betelgeuse and Rigel. On paper, as illustrated by Steven Longland here, it certainly looks convincing.

Osborn and Longland place particular emphasis on the Ing rune, seeing it as a master rune of sorts, representing imagination and the ability to transform the universe, and identifying it as a symbol of the blind eye of Odin, as the World Tree Yggdrasil, and as a pattern for the stages of life. They highlight its symmetry by halving, quartering and vertical splitting, attaching metaphysical significance to each stage. By far the longest part of this consideration, though, is spent on detailing appearances of the shape of the rune in the images of the Book of Kells, where it can be discerned in not just the overall decorative geometry of illustrations but in objects held by some of the figures. After spending an inordinate amount of time dissecting these images, in particular one from the Gospel of St John, and attaching various runic interpretations to it, Osborn and Longland do abruptly make the belated caveat that it would be a mistake to think the appearance of the Ing shape is a deliberate reference to the rune by the book’s creators; something that should be pretty obvious considering divides temporal, geographical, not to mention cultural and most importantly, religious. While one could say that the appearance of the shape and its themes might be, as Osborn and Longland call it, a meaningful coincidence, this caution is sometimes thrown to the wind and far more categorical statements are made, such as within the very paragraph where they opine that it seems likely an apparent blind eye in a depiction of St. Matthew was intended to be a veiled reference to Odin – quite the allegation to make against Columban monks.

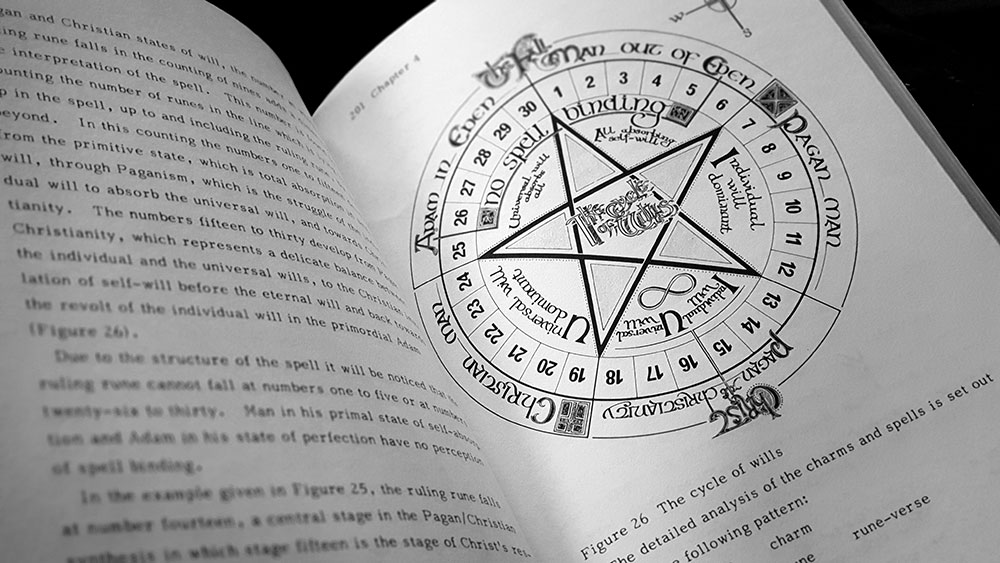

The unique selling point of Runes Games is said games, eight in all, though Osborn and Longland take their time getting to them, providing a firm grounding in the runes and the metaphysics of divination first, so that it isn’t until half way through the book that they are introduced. Beginning with the simplest, a casting of rune staves (with three of them being selected for a tri-part query), these games are various systems of divination that ramp up in complexity as they progress. Classic children’s’ games play an inspirational role here, with one game being based on a knucklebones while another is comparable to hopscotch, with runes arranged on various grid patterns and the hopping done in the player’s mind. Other games draw from mythology for their framework, with one based on the nine nights spent hanging from the World Tree by Odin, and another that incorporates the charms mentioned in the Ljóðatal section of Hávamál. Another of the games returns to the image of the World Tree but aligns it with the Qabbalistic Tree of Life, assigning various runes to the sephira and then creating five different divinatory trees, with characteristics specific to an assigned rune; for example, the Tree of Man for one’s current personality, the Tree of Aurochs for the will and the Tree of Ing for possible futures.

As the Yggdrasil game shows, there are often incredible layers of complexity associated with some of these systems, with Osborn and Longland piling interpretations and correspondences one upon the other in a lattice of interlocking potentialities of interpretation. It can be, one must admit, a little intimidating and suited to only a particular mind-set, with the cascade of variables recalling the arcane rules of a tabletop game encountered for the first time by a mere civilian unversed in the ways of geekdom. As such, some of these games feel less like, well, a game, and more like a test of wills, challenging you to see how long you can last until your eyes glaze over as you try to understand the method. With that said, the idea is that obviously, given enough training and experience in these tools and methods, the process of divination should become a lot more fluid and instinctual, without a need to constantly consult the manual.

Published by Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Thank you to our supporters on Patreon especially Serifs tier patron Michael Craft.