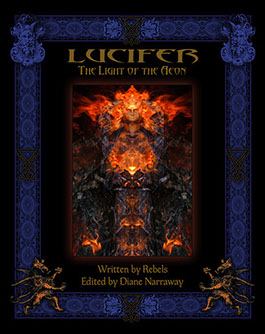

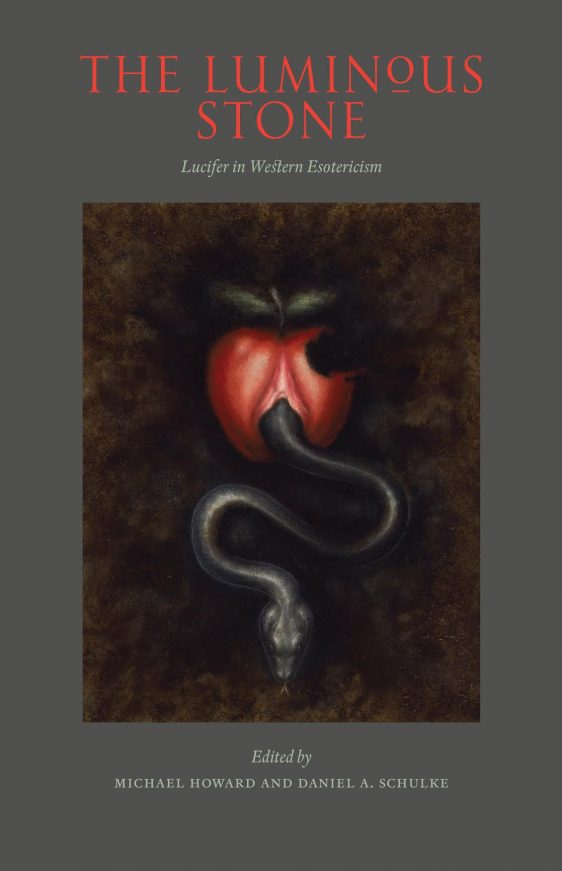

The Scalding of Sapientia is something of special issue of Anathema Publishing’s Pillars journal, which at time of writing has had three soft-cover issues in its first volume; all of which have since been compiled into a single, hardbound Perichoresis Edition. The Scalding of Sapientia sits outside this issue structure and goes straight for the hardcover, with a standalone clothbound volume wrapped in a 3/4 dusk jacket. This special edition finds its purpose in its theme, Lucifer as an exemplar of magickal consuetude, making it, along with previously reviewed books from Three Hands Press and Black Moon Publishing, part of a vigorous renaissance for the light bringer. It is Lucifer’s role as this light bringer that The Scalding of Sapientia concerns itself, casting its net wider than just a consideration of him as a mythic figure, and also exploring various themes of Luciferian wisdom, sacrifice and praxis, as well as other personifications of wisdom such as the Gnostic goddess Sophia.

The Scalding of Sapientia is something of special issue of Anathema Publishing’s Pillars journal, which at time of writing has had three soft-cover issues in its first volume; all of which have since been compiled into a single, hardbound Perichoresis Edition. The Scalding of Sapientia sits outside this issue structure and goes straight for the hardcover, with a standalone clothbound volume wrapped in a 3/4 dusk jacket. This special edition finds its purpose in its theme, Lucifer as an exemplar of magickal consuetude, making it, along with previously reviewed books from Three Hands Press and Black Moon Publishing, part of a vigorous renaissance for the light bringer. It is Lucifer’s role as this light bringer that The Scalding of Sapientia concerns itself, casting its net wider than just a consideration of him as a mythic figure, and also exploring various themes of Luciferian wisdom, sacrifice and praxis, as well as other personifications of wisdom such as the Gnostic goddess Sophia.

The contributors to The Scalding of Sapientia are a varied bunch and amongst the fourteen writers there are only a few names that immediately leap out as recognisable: Shani Oates, Craig Williams, Carl Abrahamson, Johannes Nefastos and Anathema owner Gabriel McCaughry. Things do start off slowly too, beginning with Kogishsaga, a long poem by Nukshean of the Alaskan black metal band Skaltros. Preceded by a preamble itself several pages long, the poem, which provides the lyrics to a Skaltros album of the same name, runs to eleven pages. It is presented as somewhat intimidating blocks of text, bisected only by the individual song titles, rather than more easily digestible verses. As such, it’s one of those things where you go “Well, this is nice enough and all, but I’ll come back and finish this later after I’ve read the rest of the book.” Once one realises that these are black metal lyrics, the phrasing and intonation makes more sense, and if you like, you can try and follow along while listening to the album and its corvid vocal stylings; this reviewer lost track pretty quickly.

The allure of America’s Pacific Northwest and its other mountainous and arboraceous regions is something that comes through clearly in Nukshean’s Kogishsaga and the same is true of the following contribution from Paul Waggener of Wolves of Vinland and Operation Werewolf. Both Nukshean’s piece and Waggener’s Sacrifice: Discipline & the Great Work emphasis the virtue of tribulation and time spent alone in the wilderness, with Waggener’s approach being largely an excoriation of those that don’t follow such an approach.

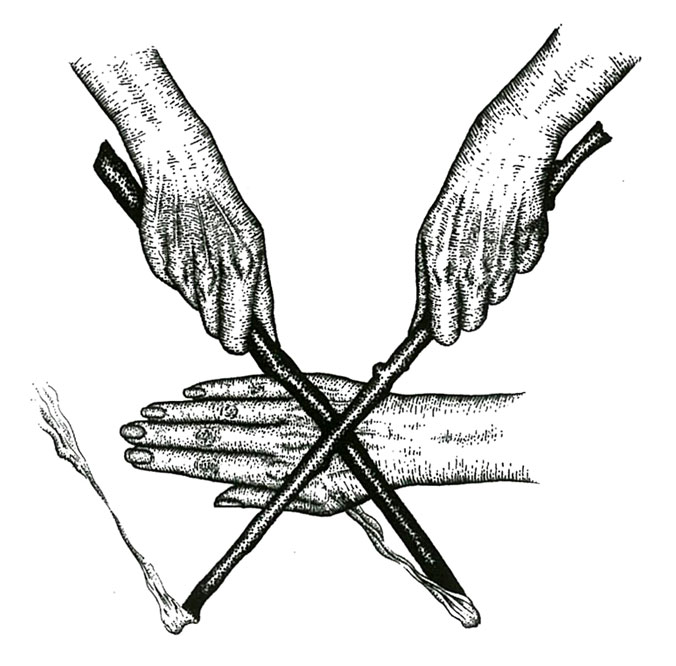

The first piece here that truly piques the interest is Johnny Decker Miller’s The Dreadful Banquet. Subtitled Sacrifice, Luciferian Gnosis & the Sorcery of the Bone Trumpet, it explores various examples of wind instruments made of bone, in particular the kangling, the human thigh trumpet used in Tibetan Buddhism. Heavily indebted to the work of Andrew Chumbley, Miller relates this instrument, its aesthetics and use to Sabbatic Craft and witchcraft in general, highlighting how an atavistic ritual such as the Tibetan Chöd can have an equivalent in more Western climes.

It is these kind of pieces, merging research with suggestions of contemporary praxis, that are ultimately the most satisfying amongst the content of The Scalding of Sapientia. They stand in contrast to more philosophical musings about the nature of the left hand path, metaphysical cosmologies, or the virtues of living alone in a cabin in the woods; none of which feel anywhere as revolutionary or revelatory as the authors probably hope they do. At this point in contemporary occultism, pretty much everything has been said in those avenues, and given that publications such as these are directed towards the choir, there seems little benefit in expatiating them once again.

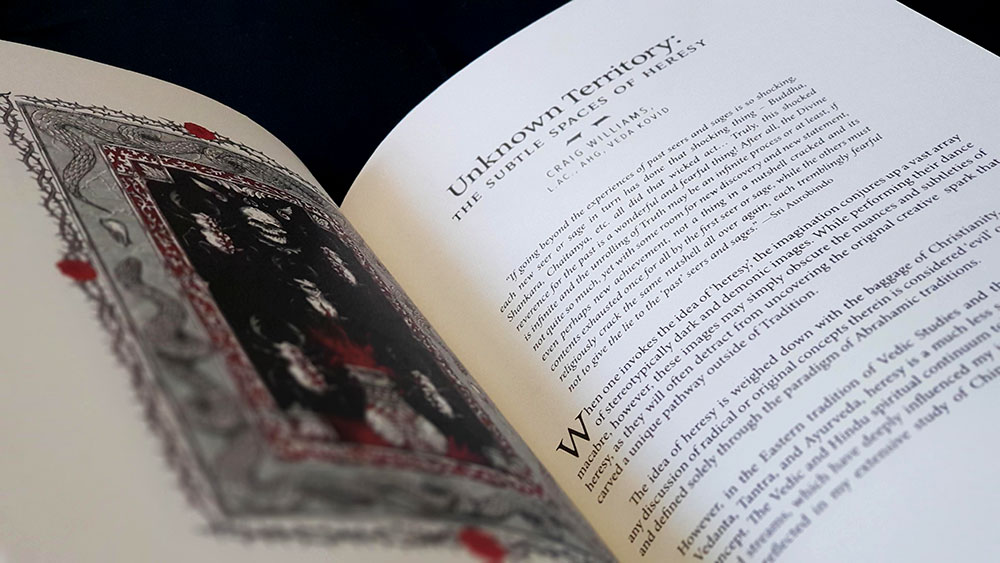

There is a strong emphasis within The Scalding of Sapientia on the experiential, of exteriorising the interior, and representing one’s personal approach to the acquisition of wisdom. Sometimes specific examples are given, and other times the practical side may be a little veiled, cloaked in philosophical speak or biographical accounts bordering on the hagiographic. In addition to the personal recollections in the aforementioned contributions from Nukshean and Paul Waggener, Craig Williams provides a succinct introduction to his Cult of Golgotha, while Camelia Elias talks of her relationship with Lucifer and of being a prodigious two year old reciting Mihai Eminescu’s poem Luceafarul. Likewise, Graeme de Villiers intersperses a dual observance mass for Our Lady of the Two Trees with a biography both magical and mundane, and Anathema-stalwart, Shani Oates writes a somewhat peregrinating paean to the entities she works with, beginning her narrative as a child who was often thought to be a changeling left by the Fey.

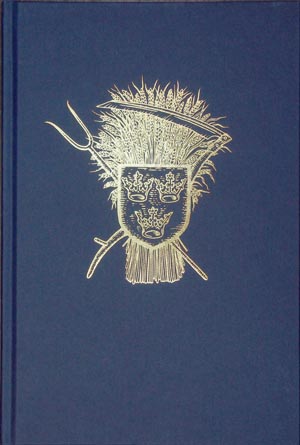

From an aesthetic perspective, The Scalding of Sapientia is a delight. Elsewhere we’ve lauded the look of releases from Anathema and this seems to have reached its apex with this release, making them the producer of some of the most beautiful books in occult publishing. McCaughry has a wonderful typographic eye, working with a suite of faces and techniques that says multiple things: occult, classic, yet paradoxically modern. Along with that, there’s an admirable use of white space and hierarchy that assists in creating that sense of rarefied environs.

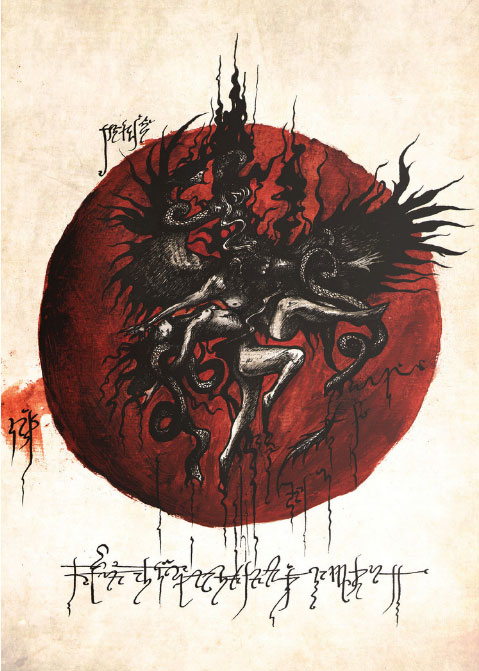

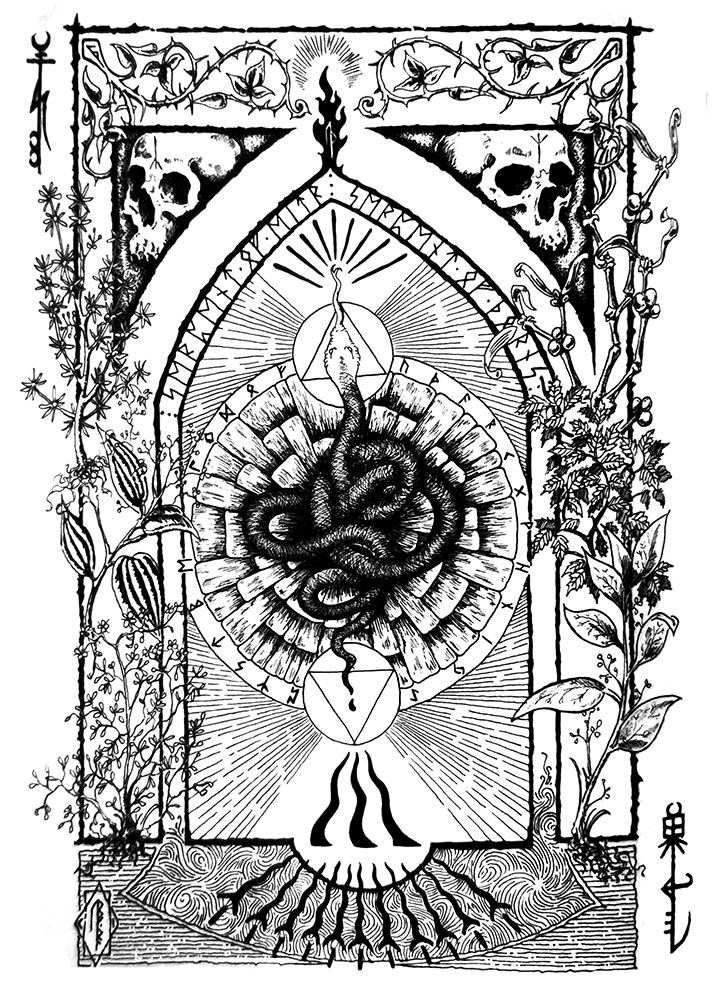

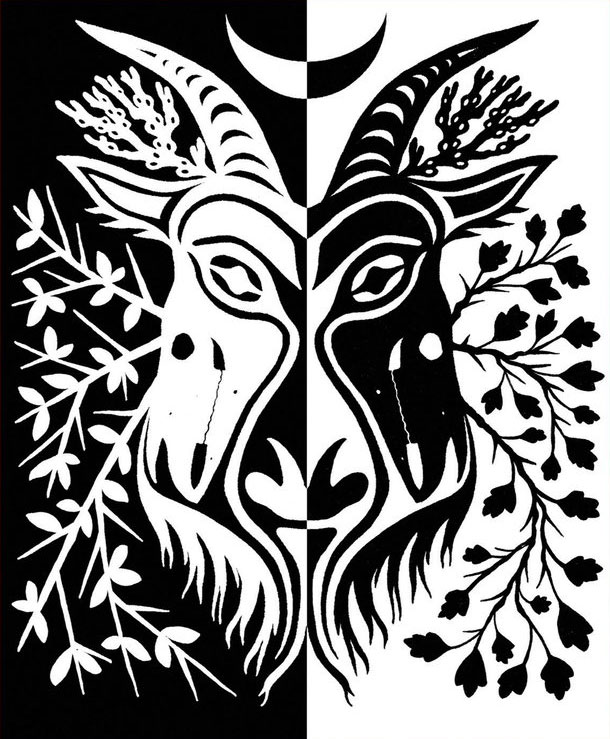

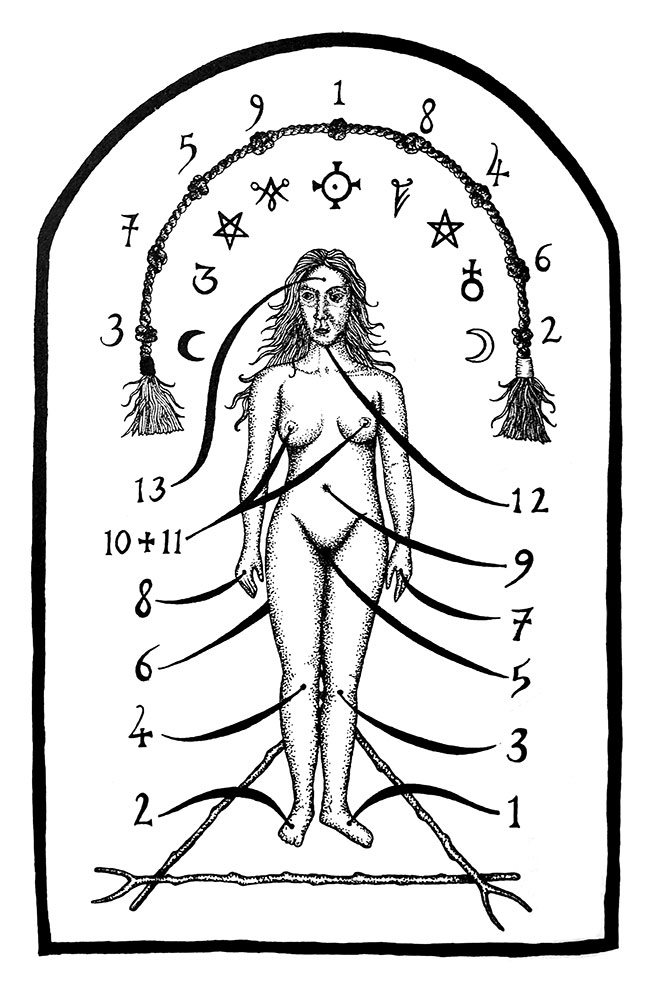

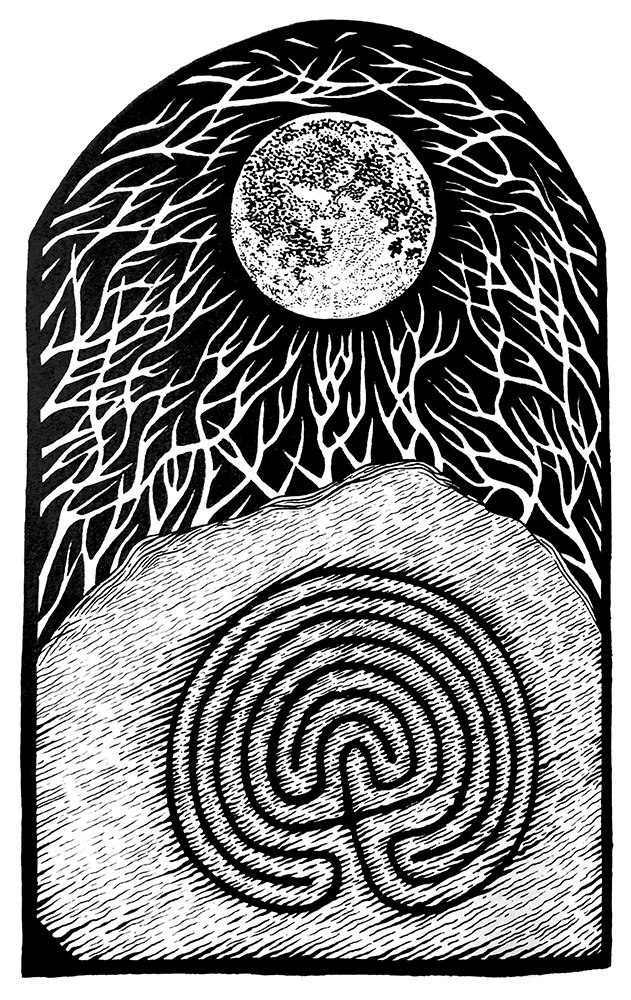

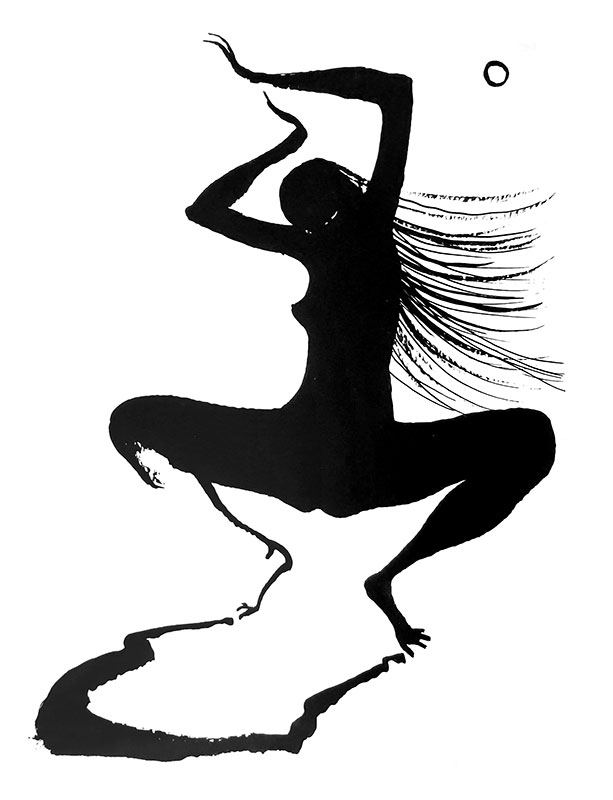

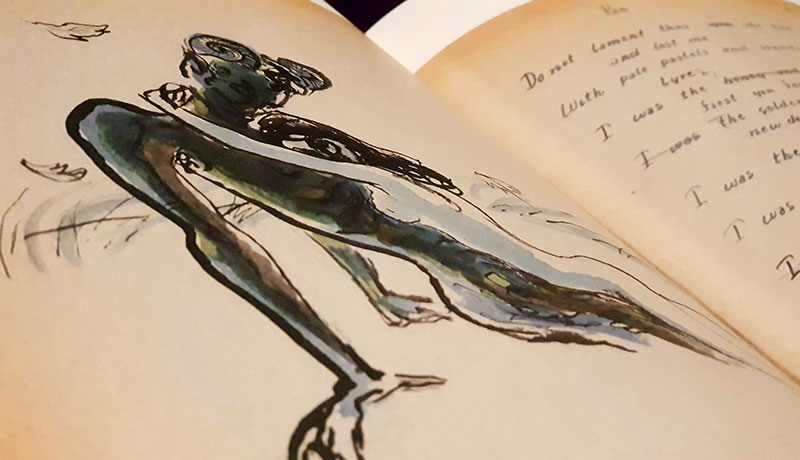

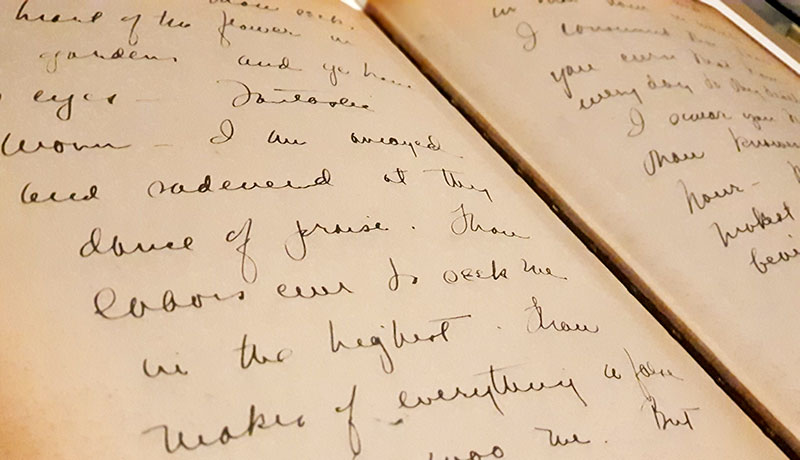

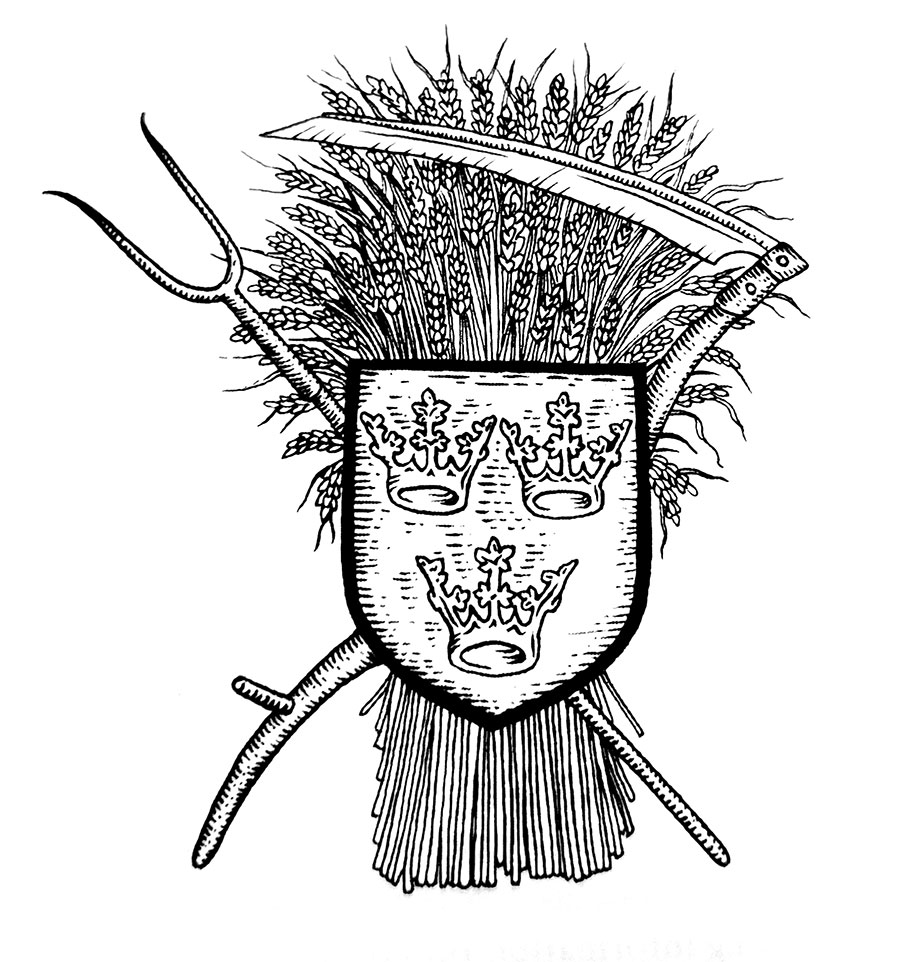

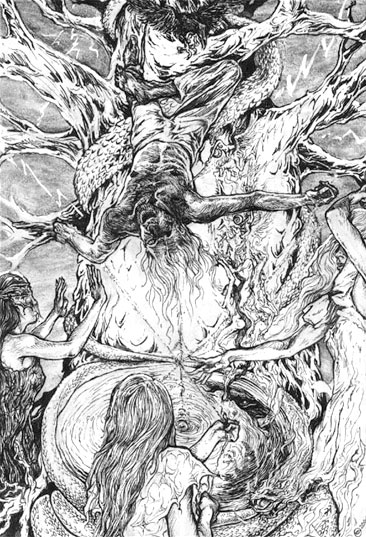

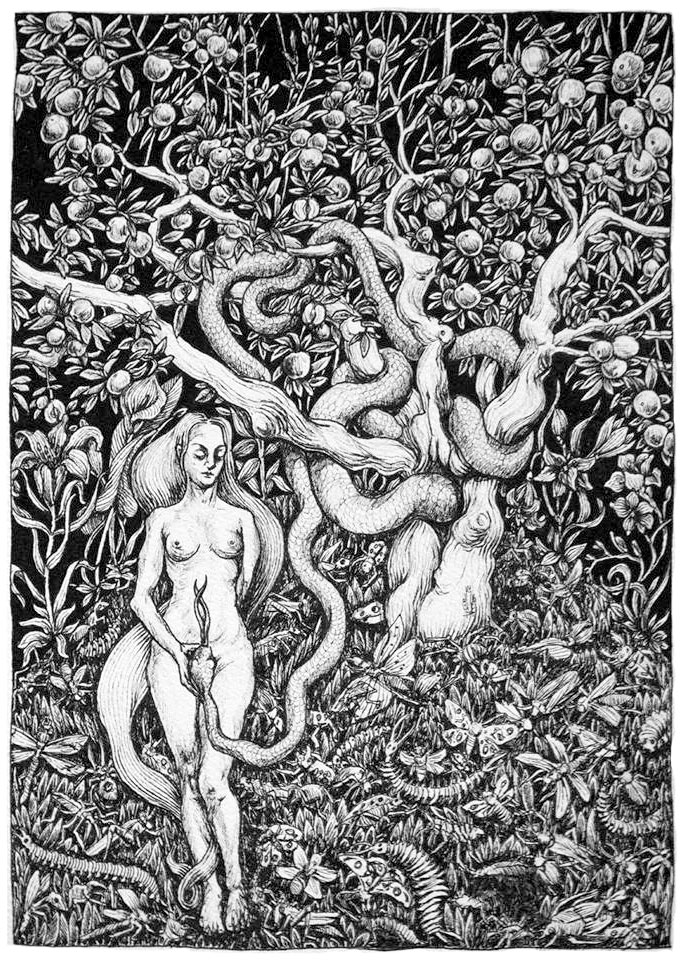

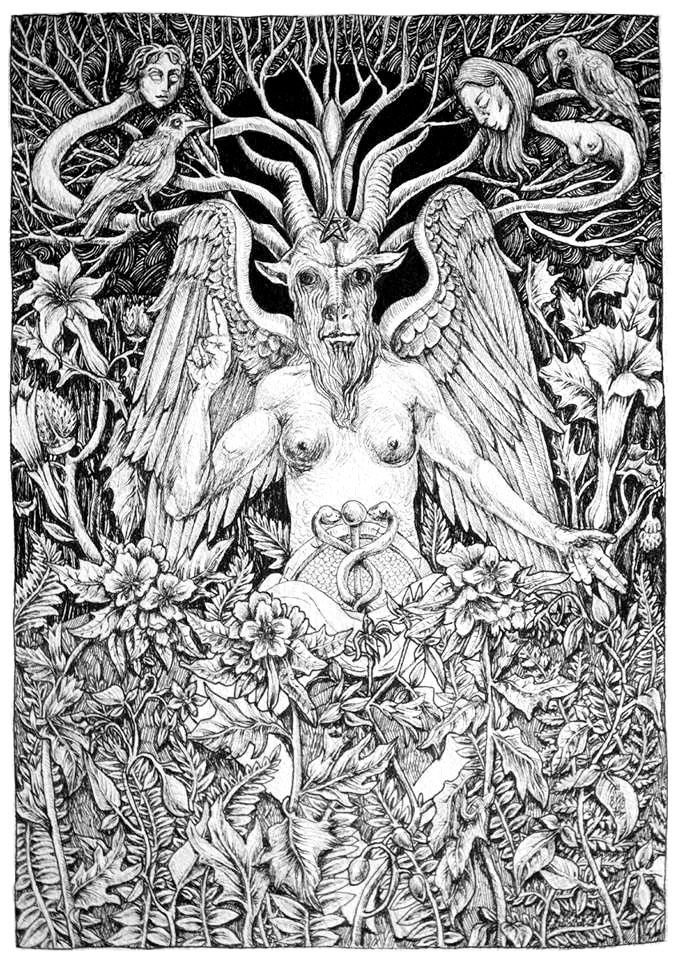

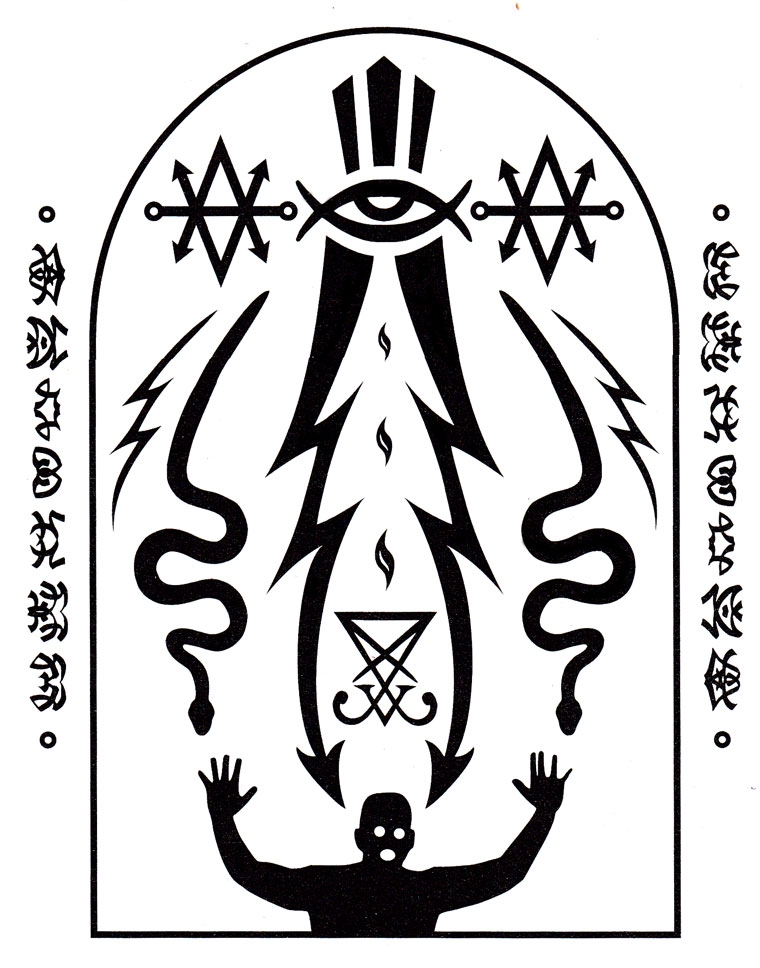

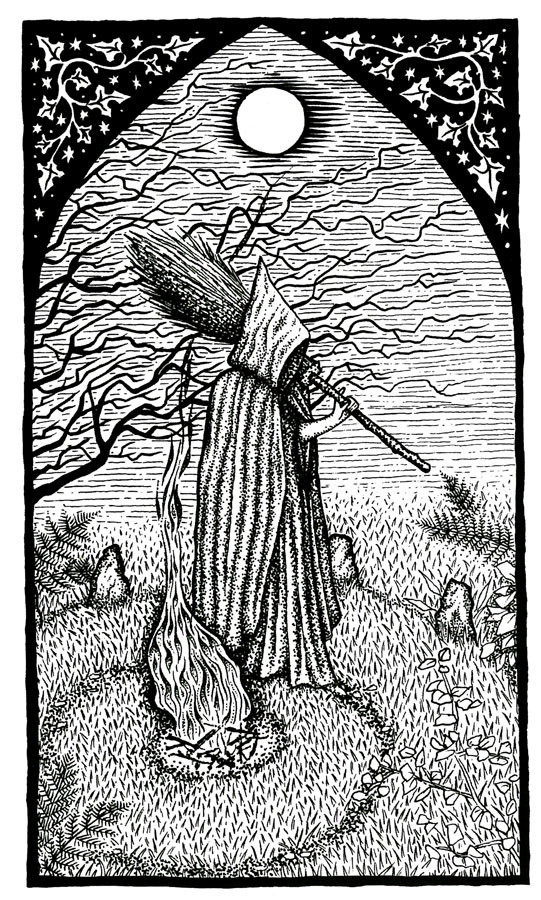

Then there’s the artwork featured throughout, which feels very curated, such is the quality, with nary a dud amongst them. Consisting of predominantly black and white images, as well as some muted and murky colour ones and a few photographs, the highlights are those such as Johnny Decker Miller illustrating his own essay, Chris Undirheimer’s eitr-tinged inks (above) and Adrian Baxter’s ikon-like botanicals. All three artists specialise in what you would hope for in contemporary occult illustration: delicately rendered fine lines and beautifully defined forms that are redolent of engravings. And skulls, always skulls. Also worthy of note is Robert W. Cook, who traffics in blackened drips and eldritch rhizomes, hued in a gloaming effulgency.

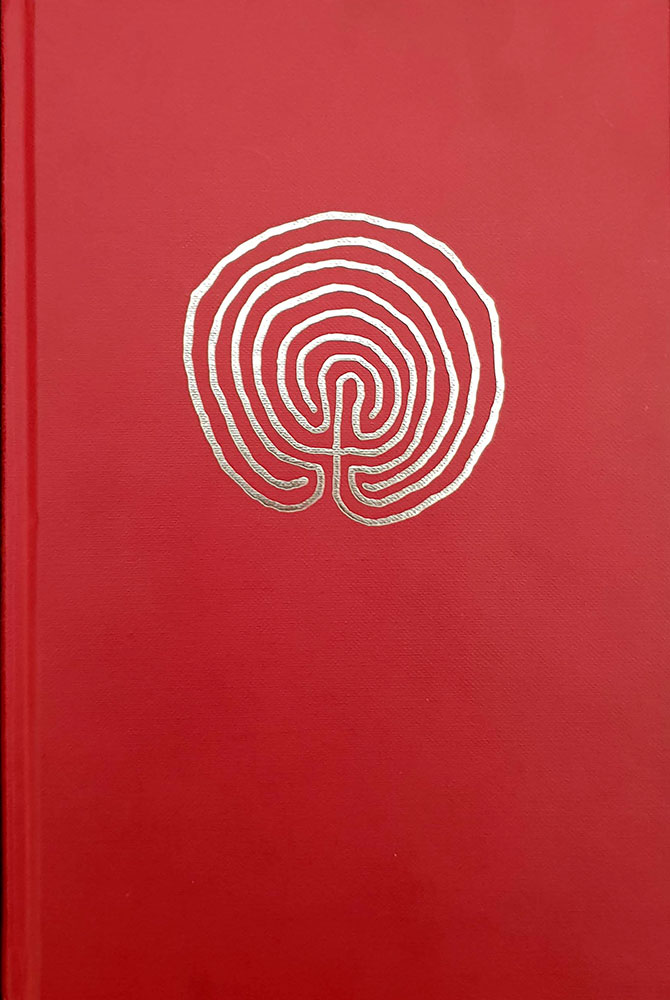

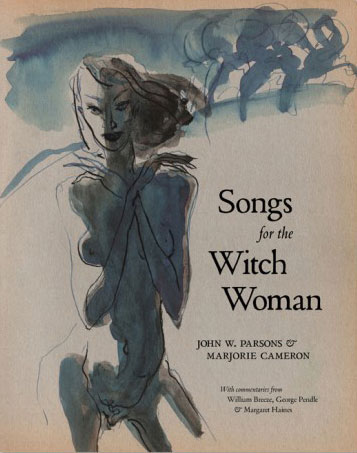

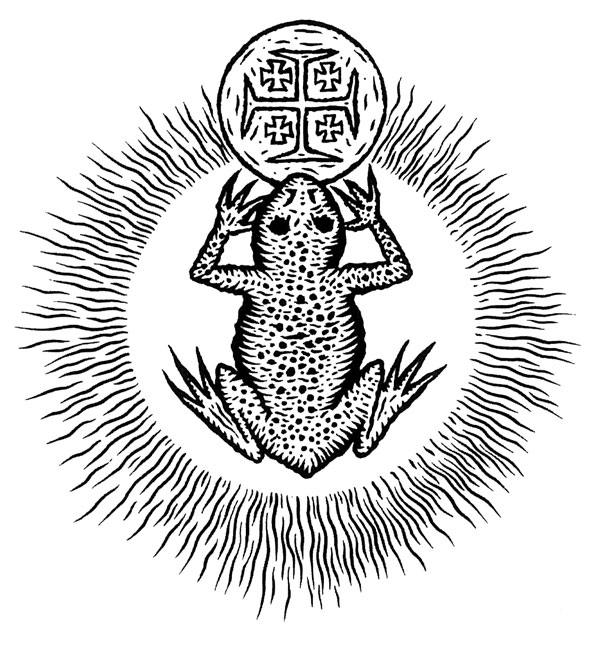

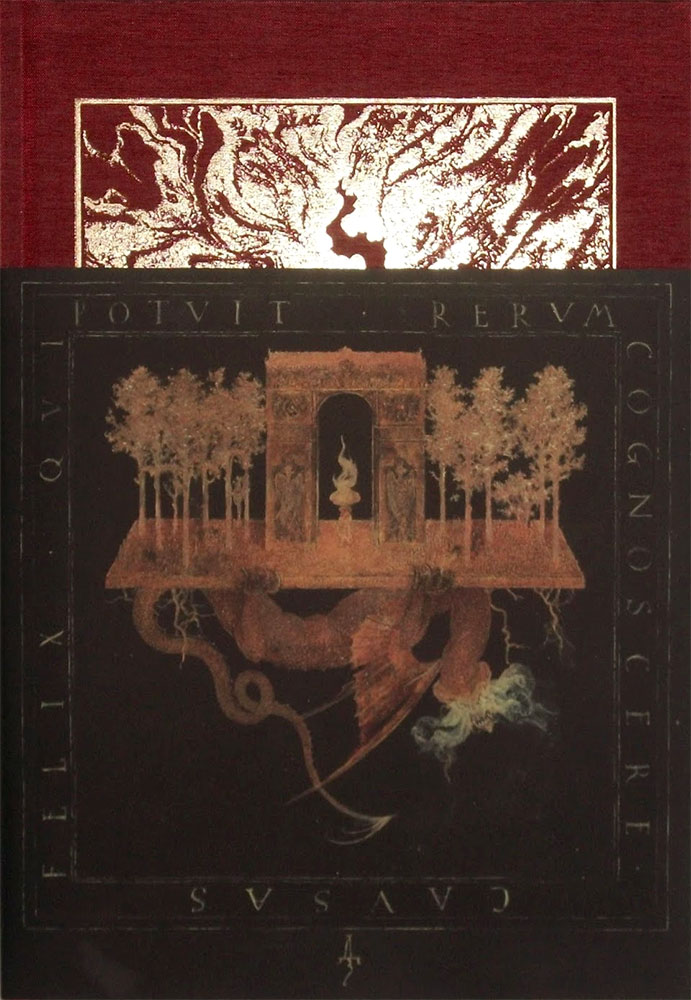

The Scalding of Sapientia was made available in two editions, a standard edition of 600 copies, and an artisanal Cutis Novis edition of a mere twelve exemplars. The standard edition consists of 208 pages on Cougar Natural 160M archive-quality paper, hardbound in a gorgeous Bamberger Kaliko metallic cranberry red bookcloth, with gold foil stamp on the spine and cover, and the sigil for this volume blind debossed on the back. Inside are Neenah Dark Brown endpapers with a burnished leather and finish, and the entire book is wrapped in the aforementioned 3/4 dusk jacket featuring the artwork Hortus Aureus by Denis Forkas Kostromitin. I’m not totally convinced by this partial dust jacket as it looks a little messy, with Kostromitin’s artwork not integrating with the gold foiled image by Undirheimer on the cloth front, and only the title on the spine bringing the two elements together.

The Cutis Novis edition is bound in a mottled, highly textured calfskin leather, with the sigil for The Scalding of Sapientia blind debossed on the front. The spine features raised nerves and the title and Pillars sigil foiled in gold, while the interior includes additional handmade endpapers. Included with each of the deluxe editions was a pine wood seal with the McCaughry-designed Scalding of Sapientia sigil burnt at knife point by Undirheimer and consecrated with the blood of both artists.

Published by Anathema Publishing