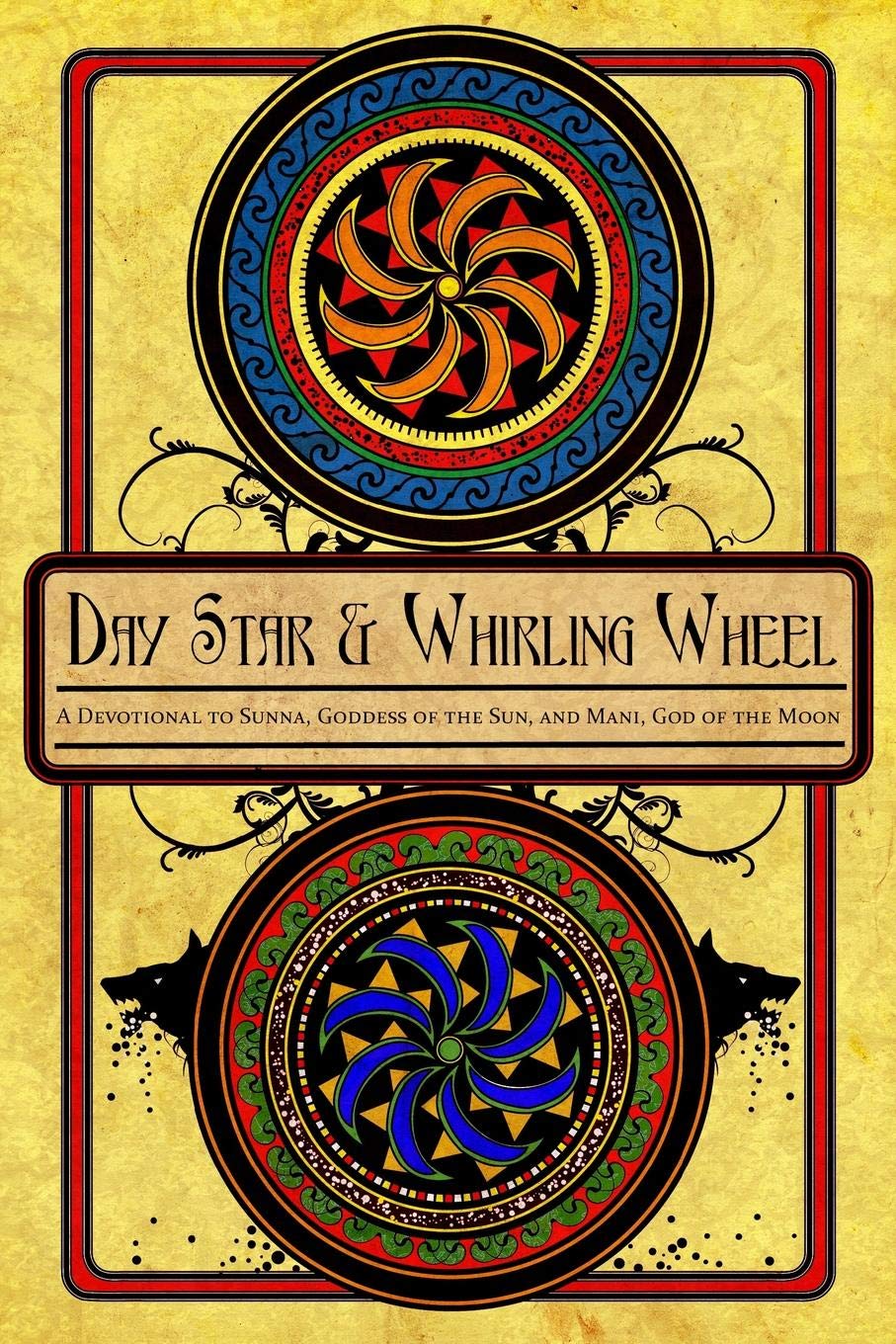

Subtitled A Devotional to Sunna, Goddess of the Sun, and Mani, God of the Moon, this book does what it says on the tin. In her introduction, editor Galina Krasskova addresses straight out of the blocks the inevitable celestial-body-sized object in the room: how do you create a devotional for two deities for whom there is but a few lines concerning them in lore, these beings who are little more than names, albeit momentous ones? Krasskova takes this more as a blessing than a curse, seeing it as opening up a world of devotional practice, unhindered by preconceptions. As expected, then, this is a book that is, for the most part, low on essays and analysis and heavy, instead, on the poetry and prayers, with a few rituals and recipes for good measure.

Subtitled A Devotional to Sunna, Goddess of the Sun, and Mani, God of the Moon, this book does what it says on the tin. In her introduction, editor Galina Krasskova addresses straight out of the blocks the inevitable celestial-body-sized object in the room: how do you create a devotional for two deities for whom there is but a few lines concerning them in lore, these beings who are little more than names, albeit momentous ones? Krasskova takes this more as a blessing than a curse, seeing it as opening up a world of devotional practice, unhindered by preconceptions. As expected, then, this is a book that is, for the most part, low on essays and analysis and heavy, instead, on the poetry and prayers, with a few rituals and recipes for good measure.

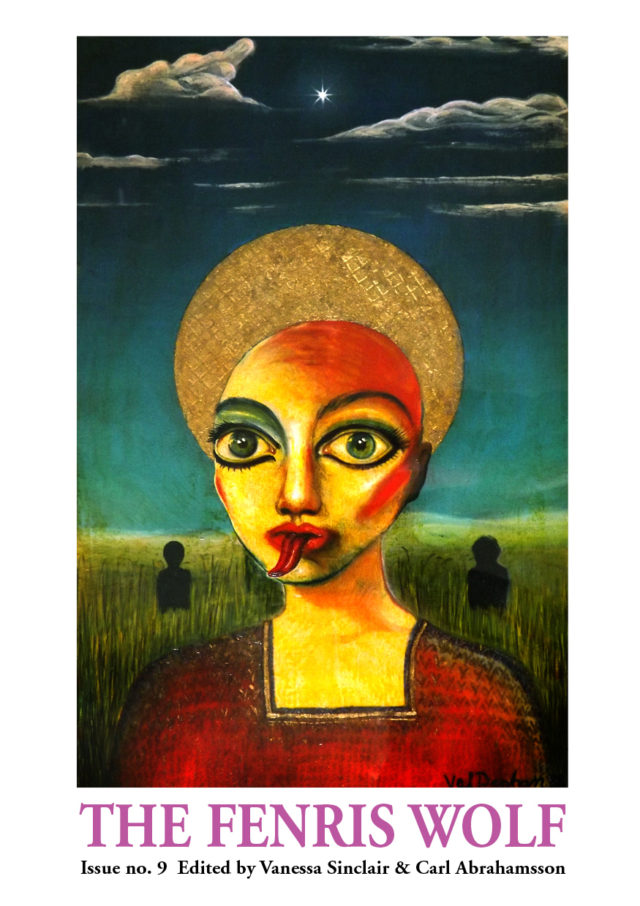

Now ten years since it was published, Day Star and Whirling Wheel emerged during Asphodel Press’ boom period, a time which saw a surge of various devotionals in the wake of Raven Kaldera’s Jotunbok and subsequent titles in the Northern Shamanism series. As such, this book mirrors others from that time, bringing together the fruits of a call for submissions that saw contributions coming from around the world, featuring some familiar names, some less familiar ones, and some anonymous ones. As is de rigueur in situations like this, I should also mention as a caveat some personal involvement in this volume, having a designer credit for the oh so striking cover image; though no involvement in any of the internal matter. Can I resist the alluring appeal of nepotism? Let’s find out.

Fittingly, given the way in which the Germanic world viewed the day as beginning at twilight rather than dawn (nox ducere diem videtur, as Tacitus noted), Day Star and Whirling Wheel opens with its devotions to Máni, the moon. Contributions in this section come from Sophie Oberländer, Fuensanta Arismendi, Andrew Gyll, Moonsinger, Heather Fortuna, Ayla Wolffe, Mordant Carnival, Rebecca Buchanan, Snaw Lafor, Seawalker Larisa Pole, Jessica Orlando, Will Oliver, Elizabeth Vongvisith, Jon Norman and several from Krasskova herself. The highlight is provided by Andrew Gyll, whose poetry collection Shadow Gods and Black Fire has been favourably reviewed before. Here, Gyll presents, as its title helpfully informs us, nine songs for Máni, combining his ability to create evocative scenes with his skill in crafting engaging and convincing dialogue as a narrative device. Within these verses, cast in crepuscular landscapes of black pools, jagged cliffs and a velvety gloom, Loki acts as interlocutor and guide, responding in a recognisably characteristic tone to the narrator’s questions regarding Mani and the passage of time: The Moon is even madder than I; I don’t think the wolf will ever catch him. Gyll follows his suite of verses with a brief essay explaining in more straight forward terms his encounters with and understanding of Máni.

Despite the diversity of contributors here, something of a consistent image of Mani emerges within the various verses. He appears as a gentle figure, as one would perhaps expect of someone associated with the moon and its commonly assigned characteristics, but he is also frequently addressed in amorous terms, being cast as a lover to the various narrators. Interestingly, this is in keeping with imagery used in Hákonardrápa by the 10th century skald Guthormr sindri which shows Máni as being capable of love or desire with the poet referring to a giantess with the kenning “desired woman of Máni.”

Before continuing on to the moon’s sister, Day Star and Whirling Wheel makes a slight diversion into other matters cosmological and astronomical with Open to the Sky. This section brings together considerations of various figures affiliated with the sun and the moon, most notably Sunna’s little known sister Sinthgunt. Although she is only mentioned in a singular verse in the Merseburg Charm, Sophie Oberländer makes much hay of this appearance, first with a prayer to Sinthgunt and then an extensive ritual for her, incorporating elements from the Merseburg Charm as well as an original liturgy. Joining Sinthgunt amongst this diversionary company are considerations of her and Sunna and Máni’s father, Mundilfœri, along with the night goddess Nott, the god of the dawn Daeg, and even an anonymous ode to the wolves who pursue the sun and moon, Hati and Skoll.

The Sunna section of Day Star and Whirling Wheel feels a little lighter than that of its nocturnal twin, but many of the same contributor names feature here too. The stellar (yes, what I did there, I saw it) piece that is every bit the equal to Gyll’s Nine Songs for Máni comes care of Michaela Macha and her Sunna-Rise. How can you resist something in which “mound-wights rise to roam among hillocks” after the shadows of night have long languidly laid, as Macha depicts Sunna’s inexorable rise above a waking world?

Day Star and Whirling Wheel is expertly formatted in the typical functional style of Asphodel Press, with a basic sense of hierarchy: serif face for body, contributor names in italics, and titles in an ever so slightly ornamented display serif. There are no standalone illustrations and instead every space is filled with a variety of presumably public domain solar and lunar images of varying quality, style and relevance; resulting in a slightly cluttered appearance where the white space could have been left well enough alone. The writing is diverse, providing a little bit of something for everyone and plenty of options for ritual work, whether it be in the complete procedures included here or just the trove of poetry’s potential as liturgy.

Published by Asphodel Press