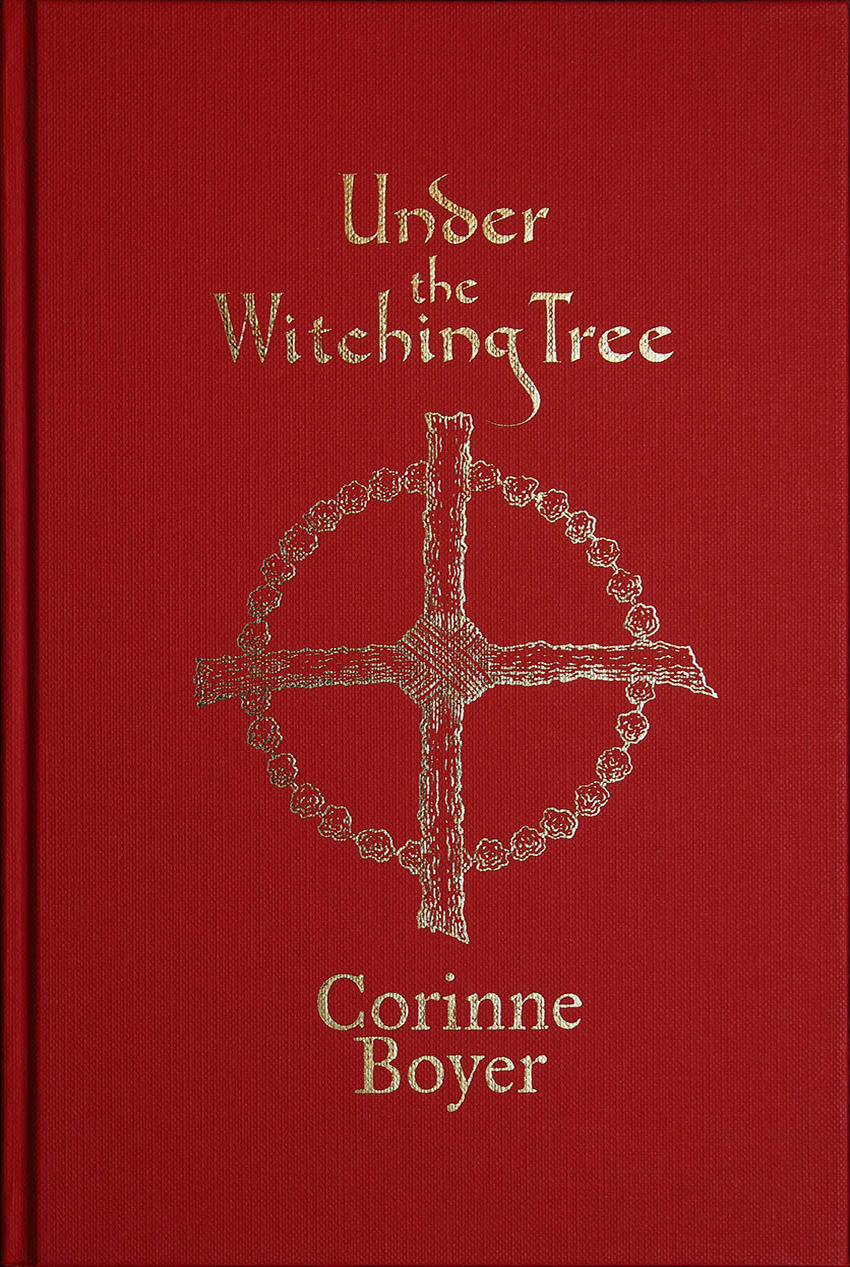

Under the Bramble Arch is the second volume in Corinne Boyer’s ongoing witchcraft trilogy and picks up where its predecessor, Under the Witch Tree, left off: still in a witchy garden near said witching tree, but moving past those arboreal inhabitants to the garden’s herbs and flowers. Bearing the subtitle “A Folk Grimoire of Wayside Plant Lore and Practicum,” the work provides a guide to 24 plants and herbs, designated by Boyer as belonging to the wayside, a locus that combines wildness with a human element, sitting on the intersection between worlds, lining byways and lanes. As such, the plants here are ones that have been with humans for some time, although many of them have occupied this space almost incidentally, as their habit is invasive or parasitic, meaning that they and their relevance are often overlooked.

Under the Bramble Arch is the second volume in Corinne Boyer’s ongoing witchcraft trilogy and picks up where its predecessor, Under the Witch Tree, left off: still in a witchy garden near said witching tree, but moving past those arboreal inhabitants to the garden’s herbs and flowers. Bearing the subtitle “A Folk Grimoire of Wayside Plant Lore and Practicum,” the work provides a guide to 24 plants and herbs, designated by Boyer as belonging to the wayside, a locus that combines wildness with a human element, sitting on the intersection between worlds, lining byways and lanes. As such, the plants here are ones that have been with humans for some time, although many of them have occupied this space almost incidentally, as their habit is invasive or parasitic, meaning that they and their relevance are often overlooked.

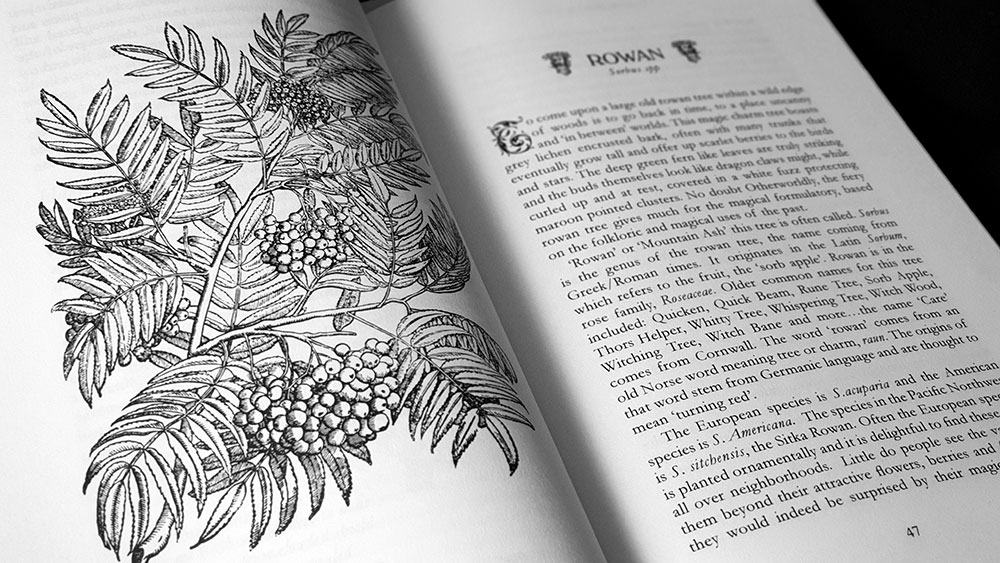

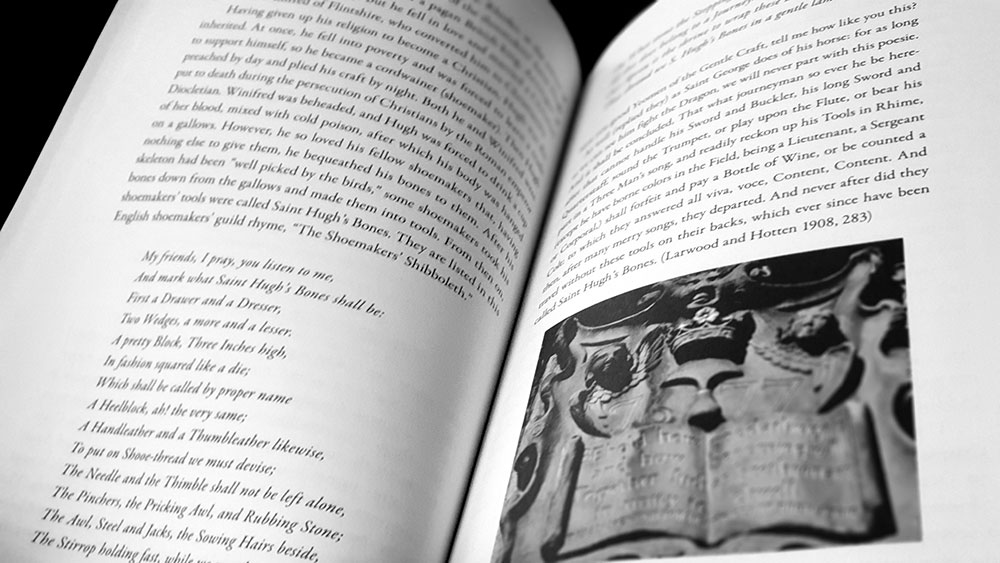

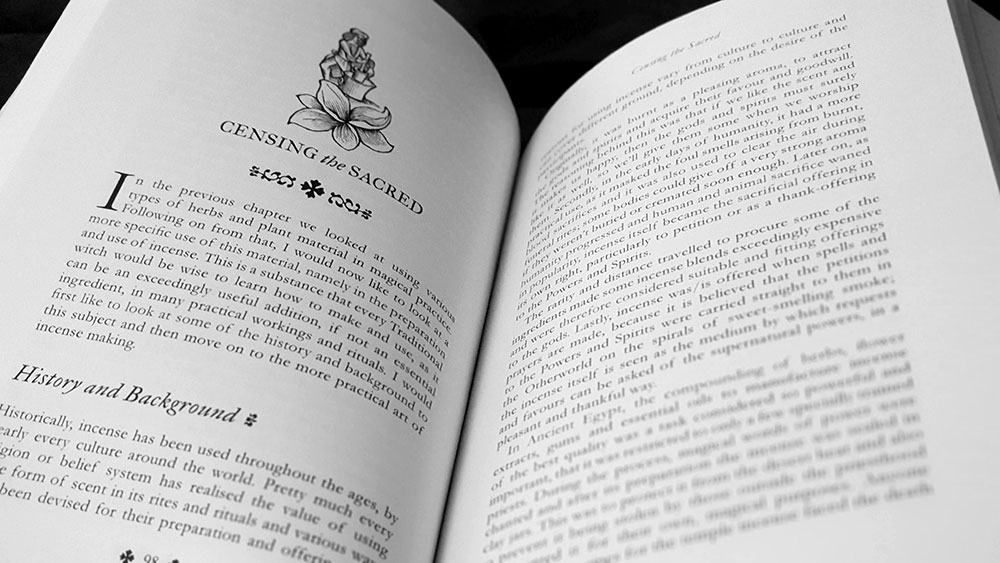

Being a review of a sequel that follows its predecessor closely in structure and theme, there will probably be a constant refrain here of “as with Under the Bramble Witching Tree,” so forewarned and forearmed, and with shot glasses at the ready, let’s begin. As with Under the Witch Tree, each of the plants is presented here as its own exhaustive entry, mini chapters as it were, containing a veritable bounty of information. As with its predecessor, each section begins with a paragraph describing the plant, using picturesque language to place its properties and persona within its own mythic landscape. Sometimes this can be a description of the plant anthropomorphised into a tangible spirit (blackberry as the lady of wild edges and shadows, bittersweet nightshade as younger sister to her more famous sibling), in others, this opening takes the form of a small paean addressed to the plant in question, whilst in others, inspiration doesn’t appear to have struck so keenly and the paragraph simply acts as a fact-based overview or introduction.

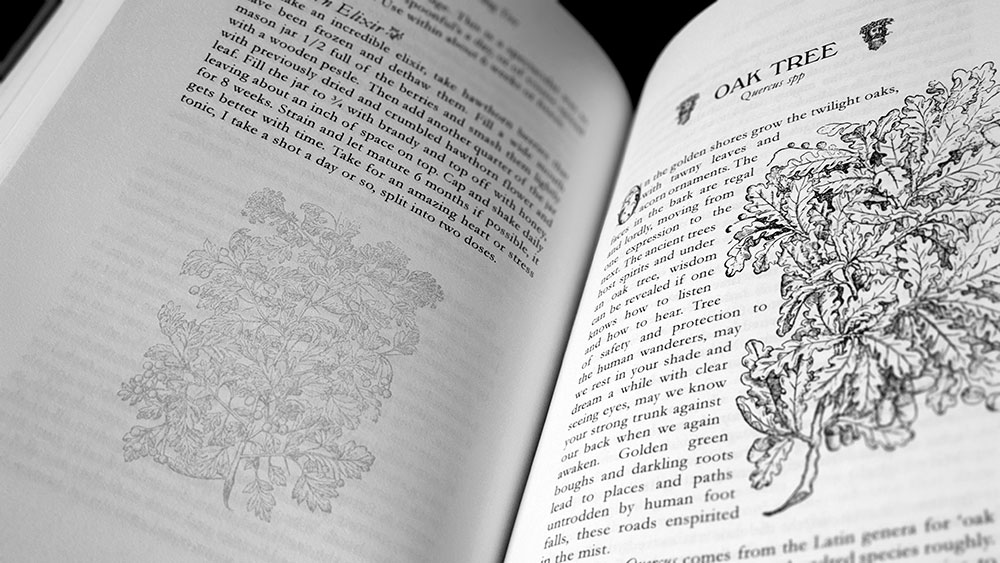

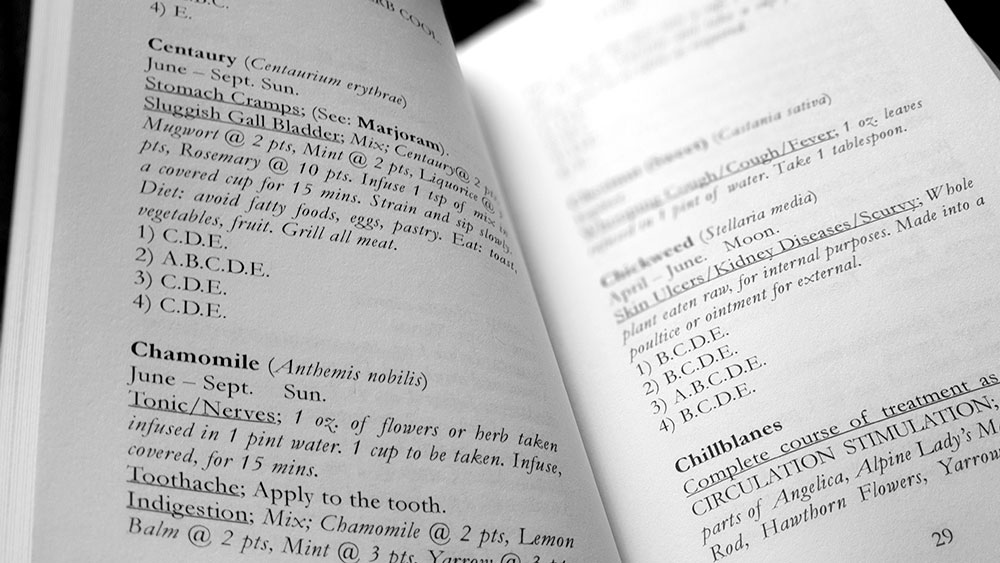

As with Under the Witch Tree, these introductions are each followed by several pages of folklore, before concluding with sections on the plant’s practical use. These practical sections begin with medical examples drawn from history, followed by Boyer’s own general application, and then usually conclude with instructions for specific tools or usages (for example, a love powder from ivy, a mugwort cauldron for scrying, or a broom from, well, broom).

The initial sections for each plant are dense and heavy with information, running to as much as six or seven pages, but usually around three. As with Under the Witch Tree, this content is presented largely unreferenced, coming thick and fast as little bites of information that apparently don’t have time to be coherently massaged into place beside their companions, the niceties of paragraph structure giving way to a need for a cascade of staccato sentences of folklore. The review of Under the Witch Tree makes much hay from the lack of referencing and whilst not wishing to re-litigate that to the same extent here, it is worth restating the issues that arise from this. The primary one is that nothing can be trusted, as so many of the anecdotal facts are shorn of their context, particularly geographical or temporal, with a belief that may have been extant in only one area often becoming seemingly universal because its point of origin is not mentioned. Any time something doesn’t ring true, the reader can find themselves hurrying off in search of the unnamed original source or some other form of corroboration, not in an attempt at playing ‘got-cha’ but just to verify that it’s true, or to find either a broader context or actual specifics. In the end, this all comes across like herbalist notes that have been scribbled down over the years, perhaps with their original sources long forgotten, but then transposed to the final manuscript without much in the way of finessing, resulting in the frequent sentence fragments, awkward phrasing, and disorientating shifts in tense.

As with Under the Witch Tree, one can, with a bit of work, reverse engineer the content here, tracking down the source of information (for example, much of the content about blackberry comes directly from Maida Silverman’s A City Herbal; listed in the bibliography but not cited in-body). But this is often an equally fruitless (eh hem) task, as these sources can be as citation-deficient as the book drawing from them. This makes much of the information here all but useless, vulnerable to such a degree of cumulative error and generation loss that it can be no better than gossip or urban legend.

This all works if you want the book to provide an overall vibe of these plants, where a witch could potentially pick any vaguely mentioned property or procedure and deem it fit for purpose based on general associations and history. Indeed, one could generously suggest that this is simply in line with the book’s precedents, with herbals and florilegia of old hardly being hotbeds of exhaustive referencing. However, if you incline towards the scientific method, documented provenance and things empirical, from either a botanical or anthropological perspective, then you are going to be severely disappointed. Hammering this home may seem unduly cruel, and one could argue that the book was never intended to be as rigorous as one might like, but the sentiment is borne simply from the experience of reading, where constant encounters with either the abrupt, note-taking nature of the writing, or the insufficiently detailed content of what could otherwise be interesting facts, can make for a frustrating experience. Then there are moments that are not just ambiguous in their origin but flat out wrong, such as a claim in the section on mistletoe that Baldur was the son of Freyja and that after he was restored to life, she placed the parasitic plant under her protection and it thenceforth only ever brought good fortune. With a bit of digging, this monumental howler seems to have come unchecked from a 2006 issue of Homeopathy Today Online, which tells you everything you need to know right there.

In contrast to this torrent of not always accurate botanical information, the practical exercises that Boyer includes have the benefit of a far more immediate provenance, all coming from her. There are a variety of exercises presented here, with the various plants being used not just for medicinal products like tonics and ointments, but for charms and amulets, and for magical tools such as a witch’s rope, hag tapers, brooms and various aides to scrying. In some ways, this is where the book excels, with a diverse selection of exercises, well thought out and equally well presented.

As with Under the Witch Tree, Under the Bramble Arch concludes with a set of appendices with emphasis on the practical, as Boyer presents instructions for being a home apothecary, with guides to making poultices, tinctures, infusions and teas; all techniques that can be applied to different plants. As noted in the review for the previous volume, this is a good way to do it, rather than cluttering up each individual section with repetitive instructions.

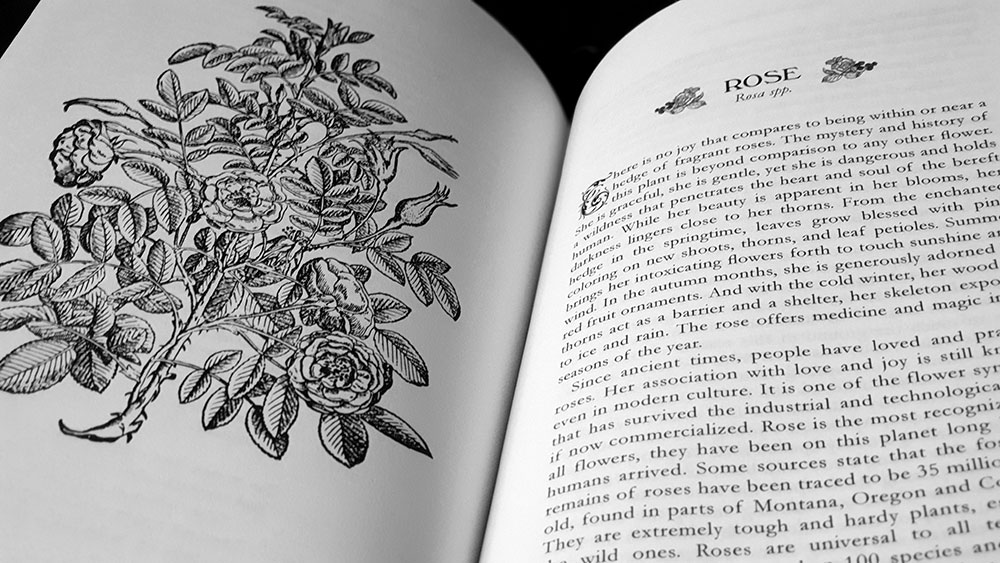

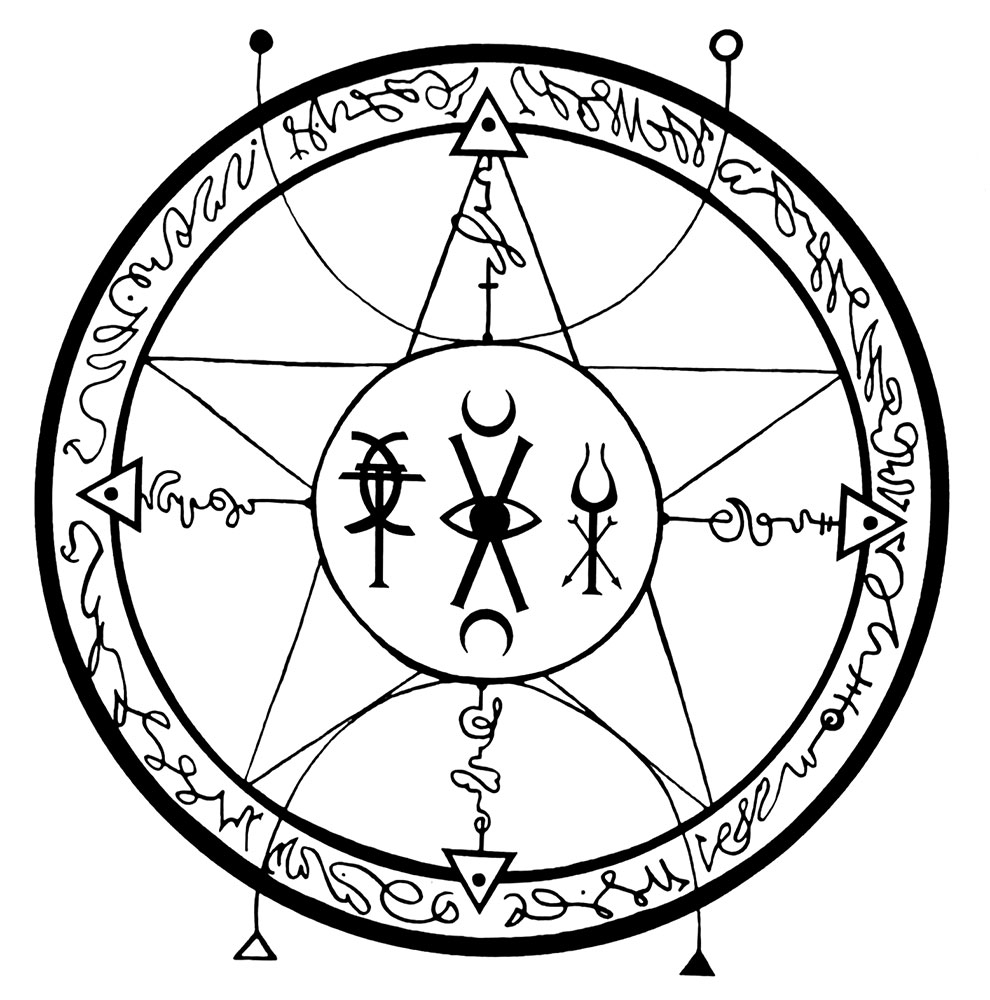

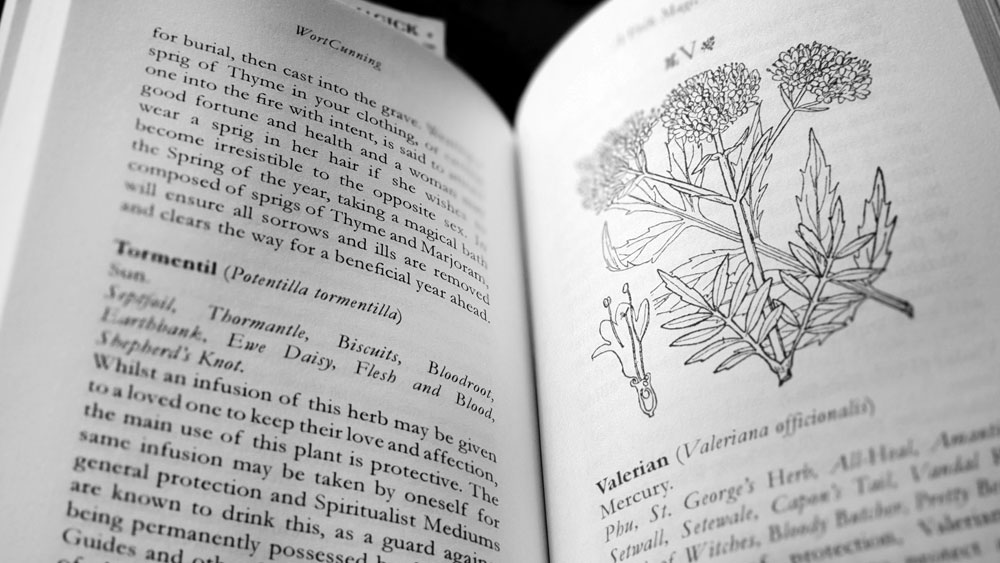

As with Under the Witch Tree (*hic*), the entries for each plant are formatted to begin on the recto side of the page spread, and are usually preceded by the plant’s botanical illustration, printed at full size, on the verso page; save for a few times where the image is instead included text-wrapped in the main copy. As with Under the Witch Tree, these images come from a variety of, one assumes, public domain sources, and so they are not consistent in weight or style, with some appearing particularly heavy in line compared to others. But, unlike similar situations in lesser books, there’s a level of care that has gone into the presentation here and each image is of acceptable quality, with no pixilation or artefacts from compression or low resolution.

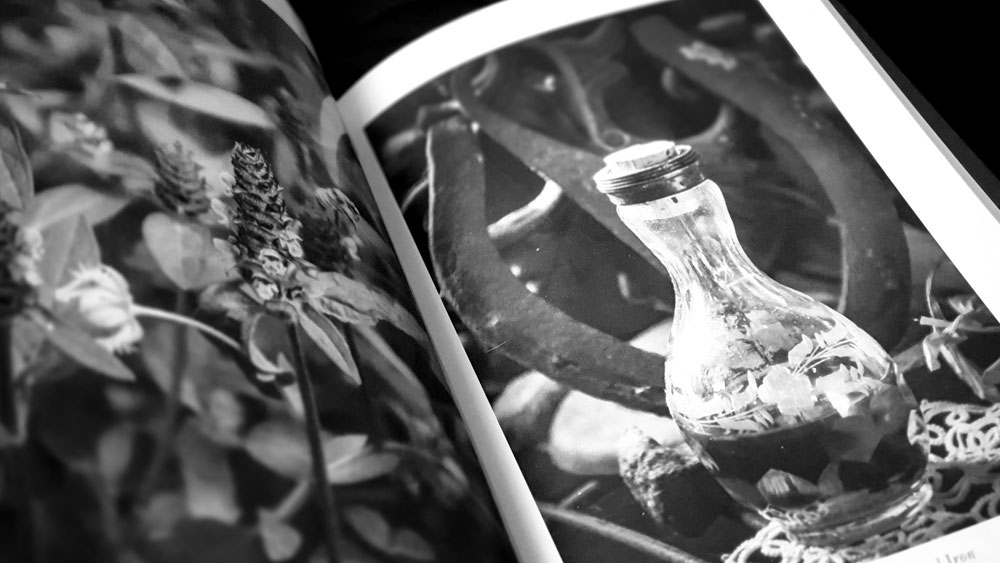

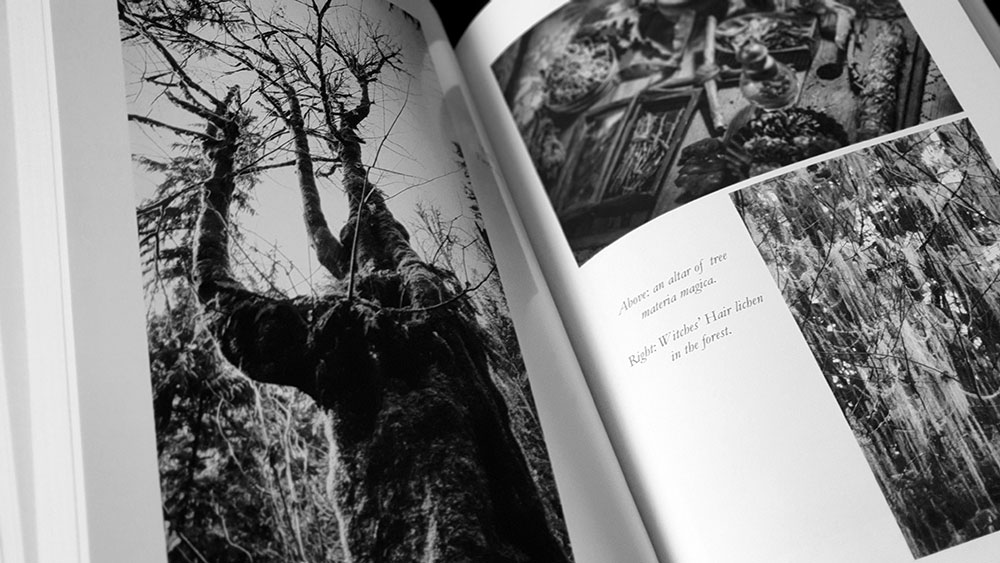

In addition to these illustrations, Under the Bramble Arch includes a section of gloss photograph plates in the centre of the book. These feature images of Boyer herself (in her garden and with broom), along with both examples of some of the plants discussed and a variety of their uses. Richly black and white, these are beautifully shot and add a realism and hands-on quality to what is presented here, contrasting with the more idealised nature of the botanical illustrations.

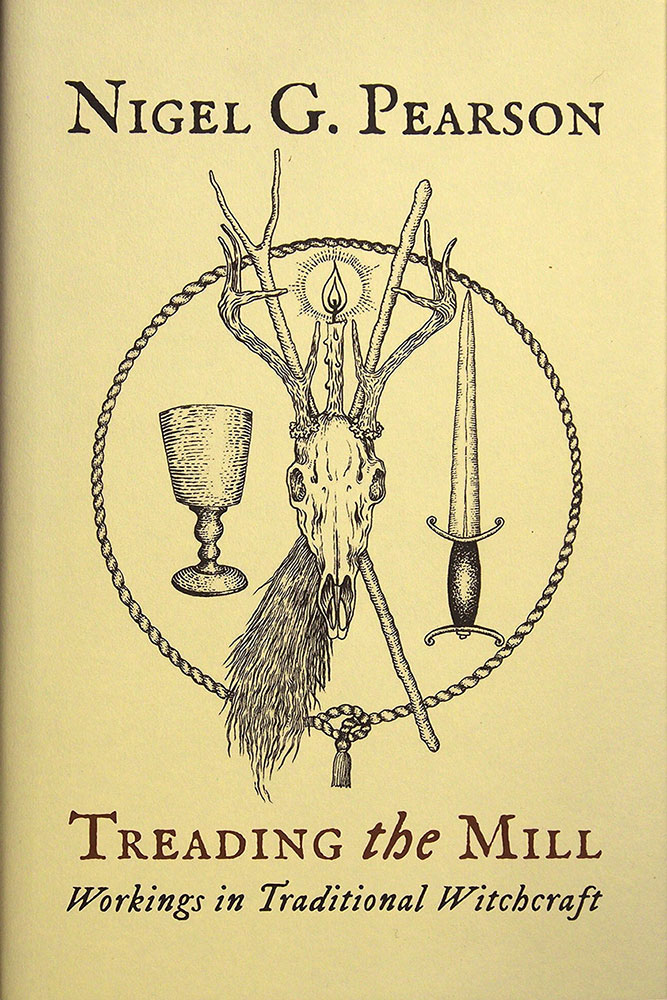

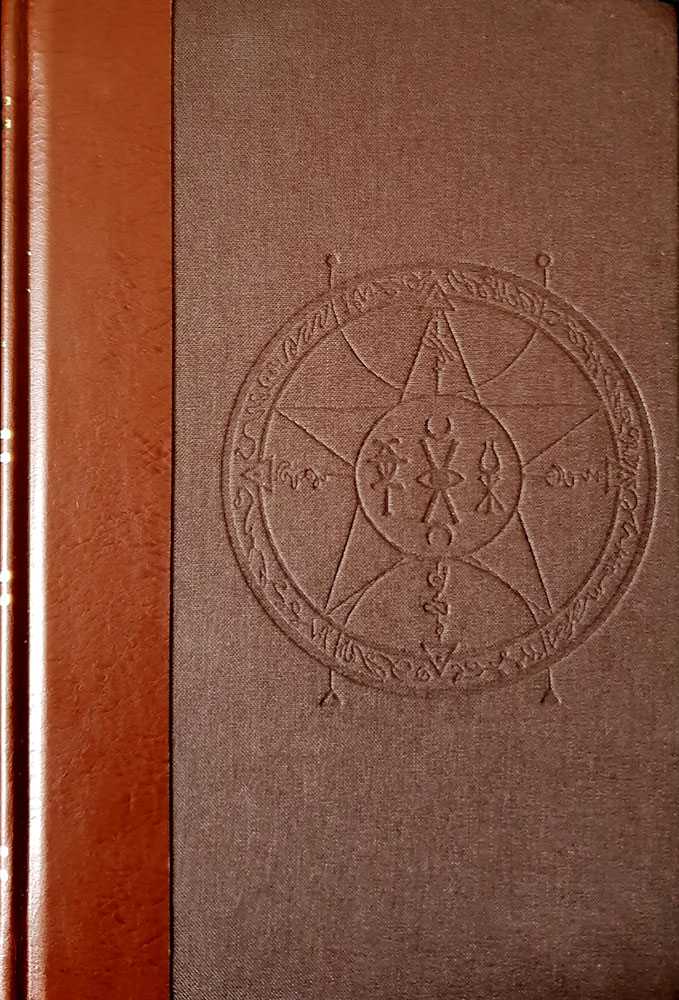

Under the Bramble Arch is presented in Royal format with 258 pages and the 24 pages of the black and white photo plates. It was released in four editions: paperback, standard hardback, special edition and fine edition. The paperback edition comes with a gloss laminated cover while the standard hardback edition is bound in a blackberry cloth with gold foil blocking to the front and spine, green endpapers and green head and tail bands. The 250 copies of the hand-numbered special edition are bound in dark green cloth, with gold foil blocking to the front and spine, blackberry endpapers, and green head and tail bands. Finally, the sixteen copies of the fine edition are hand-bound in dark green goat leather with gold foil blocking to the front and spine, and the image of goat from the other editions replaced by the blackberry engraving used within. Housed in a fully lined black library buckram slip-case with blind embossing on the front, the fine edition also includes a hand-written protection charm by the author, using ink made from roses.

Published by Troy Books

Thank you to our supporters on Patreon especially Serifs tier patron Michael Craft.