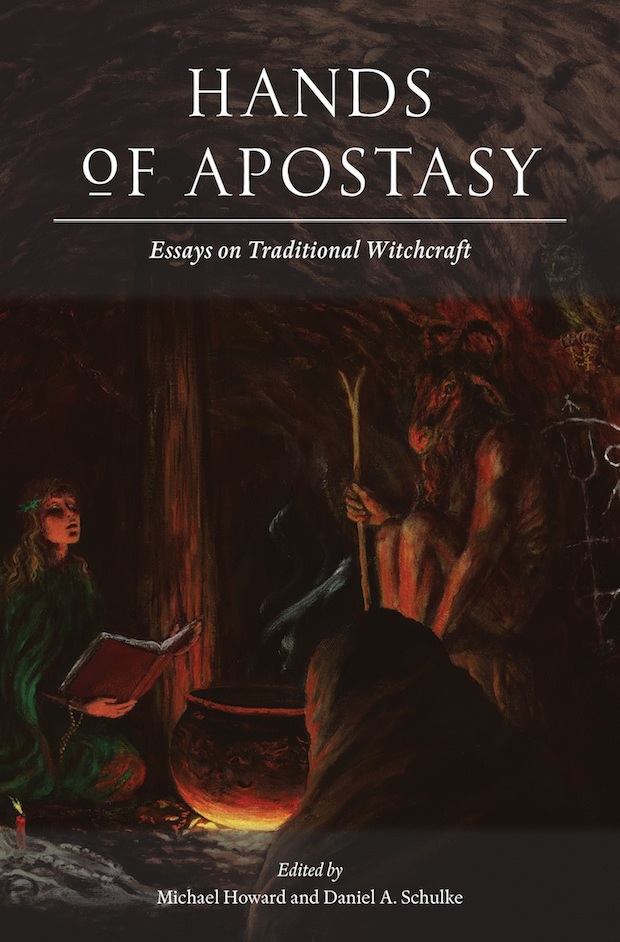

First, a eulogy: recently departed Michael Howard (1948–2015) was quite possibly my gateway drug to occultism. His Wisdom of the Runes was the first book I read on runic magic and his magazine, The Cauldron, provided my first tantalising insights into Robert Cochrane’s Clan of Tubal Cain (way back in the pre-internet days when there was a lot less info about and precious little mentions of him and the Clan in books). A survey of Scriptus Recensera entries show that a significant amount of his work has been reviewed here: The Book of Fallen Angels, an issue of The Cauldron, his important tome Children of Cain, and most recently, Hands of Apostasy, which he co-edited with Daniel Schulke. This, needless to say, was not by design but a mark of how prolific he was and how well his oeuvre matched my interests. I always found Michael so thoroughly genuine, something frustratingly rare in these circles where smoke and mirrors dominate and where people spend so much time shoring up their claims to some amazing lineage, or trying desperately to appear privy to some amazing knowledge or in possession of equally amazing skills and power. He had such an obvious passion for the magickal milieu within which he lived. As I remarked in my review of Children of Cain, Michael’s approach to things magickal could be said to have a Mulder-like willingness to believe that was tempered with a Scullyesque critical approach that cautioned him against totally subscribing to anyone’s claim; at least in print. He always seemed willing to entertain someone’s claims, not in a blindly, uncritical manner, but rather in an “it’d be nice if it’s true” kind of way. Witness his patronage of Bill Liddell and the claim that Essex cunning man George Pickingill was actually a grand master of nine covens who had direct influence on everyone from Gerald Gardner to the Golden Dawn. As I noted in my review, it is an appealing theory, and one can’t help feeling that Michael gave it as much space over the years as he did (in both The Cauldron first and later in Children of Cain) because of just how glorious its grand vision is. By no means did he ever state, to my knowledge, his acceptance of Liddell’s claims, but there’s a feeling that he wished they were true. And why not?

First, a eulogy: recently departed Michael Howard (1948–2015) was quite possibly my gateway drug to occultism. His Wisdom of the Runes was the first book I read on runic magic and his magazine, The Cauldron, provided my first tantalising insights into Robert Cochrane’s Clan of Tubal Cain (way back in the pre-internet days when there was a lot less info about and precious little mentions of him and the Clan in books). A survey of Scriptus Recensera entries show that a significant amount of his work has been reviewed here: The Book of Fallen Angels, an issue of The Cauldron, his important tome Children of Cain, and most recently, Hands of Apostasy, which he co-edited with Daniel Schulke. This, needless to say, was not by design but a mark of how prolific he was and how well his oeuvre matched my interests. I always found Michael so thoroughly genuine, something frustratingly rare in these circles where smoke and mirrors dominate and where people spend so much time shoring up their claims to some amazing lineage, or trying desperately to appear privy to some amazing knowledge or in possession of equally amazing skills and power. He had such an obvious passion for the magickal milieu within which he lived. As I remarked in my review of Children of Cain, Michael’s approach to things magickal could be said to have a Mulder-like willingness to believe that was tempered with a Scullyesque critical approach that cautioned him against totally subscribing to anyone’s claim; at least in print. He always seemed willing to entertain someone’s claims, not in a blindly, uncritical manner, but rather in an “it’d be nice if it’s true” kind of way. Witness his patronage of Bill Liddell and the claim that Essex cunning man George Pickingill was actually a grand master of nine covens who had direct influence on everyone from Gerald Gardner to the Golden Dawn. As I noted in my review, it is an appealing theory, and one can’t help feeling that Michael gave it as much space over the years as he did (in both The Cauldron first and later in Children of Cain) because of just how glorious its grand vision is. By no means did he ever state, to my knowledge, his acceptance of Liddell’s claims, but there’s a feeling that he wished they were true. And why not?

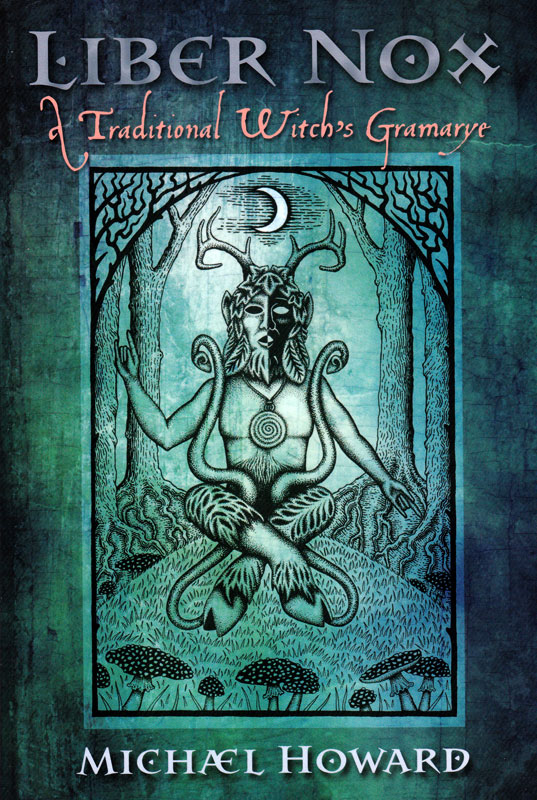

Until Xoanon and Three Hands Press publish any of the unpublished texts they have in their archives, Liber Nox is the last major writing from Michael Howard and, in many ways, stands as a fitting testament to him. It consolidates much of what Howard has considered over the years in matters of traditional witchcraft, providing it in a format that prefaces everything with a lot of broad anthropological examples and explanations, and then concludes with a breakdown of the wheel of the year and a series of corresponding rituals. As such, it contains more factual information than your average grimoire, or your bog-standard rituals-and-recipes book for that matter, and is all the more satisfying for it.

In the first section, Preparing for the Rites, Howard explains the symbolism of various ritual tools, elements and procedures. Rather than the usual cursory explanation one would expect in other books, this digression is a significant one that facilitates a wider exploration of the themes of witchcraft. As was sometimes the case in his writing, Howard’s approach here can sometimes be a little info-dumpish, with a wealth of information being presented but relatively little discursive dialogue to provide pacing or highlight, admittedly self-evident, connections or motifs. There is also no referencing, except for the very occasional in-text citing of sources for specific quotes, so while you never doubt the accuracy of Howard’s facts, there is the occasional niggling feeling of needing to fire up the old Google machine to see what his source might have been for a particular nugget of gnosis.

A similar approach follows in the second section, The Wheel of the Year, where said wheel and its associated festivals provide an opportunity to consider in depth various folklore and witchcraft themes. A discussion of Candlemass, for example, is able to embrace the goddess Brigid and her saintly incarnation as St. Bridget, as well as the Cailleach, goddesses of Sovereignty, and loathly ladies. Similarly, a discussion of May Day gives insight not just into figures such as the May Queen but unicorn symbolism, the underworld journey to the Castle of Roses and Sir Gawain’s encounter with the Green Knight. Often the matters discussed for each festival seem almost tangential to the extent that you lose track of where it all began and which celebration is up for discussion. This is, by no means a bad approach, and in fact I’m rather partial to it. It means that rather than the kind of brief cursory description of a festival you can find in any book on witchcraft, Howard’s style paints a wider, more holistic picture, which places these events within a greater magickal world of interrelating symbolism and themes.

Thus, this second section of folklore and festivals, which is easily half of the book, provides what is effectively a thorough consideration of traditional witchcraft, shot through this anthropological lens. It is only in the book’s third section, the Liber Nox proper (gloriously subtitled The Rites of the Black Book of Shades), that the reader encounters the kind of ritual material one would perhaps expect of the gramarye promised in the subtitle. Howard prefaces his rituals with a consideration of the year which consolidates the mass of material from the previous section into a narrative of changing seasons, rising and falling deities, and elements waxing and waning. He makes it clear that the rituals presented here are not from any particular tradition but have been written entirely for this book, incorporating aspects from various traditional witchcraft sources and obviously the folklore of the wheel of the year. There are certainly elements you can spot, with the imagery of the Clan of Tubal Cain, for example, coming through clearly in the use of dancing mills and castles.

The first of the rituals is an all-purpose casting of the circle of arte, followed by instructions for a concluding houzel and a closing of the circle. Then follows rites for all the previously considered stations of the year: Yule, Twelfth Night, Candlemas, Lady Day, May Day, Midsummer Day, Lammas, Michaelmas and Hallow. Perhaps not surprisingly, there’s a pleasant, expert style to these rituals, indicative of the experience and expertise that Howard had. The liturgy is beautiful but simple and refined with no ornate archaisms and nothing you’d feel too silly saying out loud; a constant ritual concern of mine. There is also a variety of activities, and despite the use of very specific structure, there’s less of the usual rote feeling of intone *variable,* do *variable,* banish, and goodnight everybody! Many of the rites feature variations of circular dancing, often incorporating intertwining ribbons, while in the ritual for Midsummer Day, two additional stang are used to form a gateway to the realm of Fey through which celebrants visualise themselves passing.

With its carefully considered structure of anthropology followed by, erm, ritualology, Liber Nox, makes for a satisfying read. It incorporates so much of what Howard considered in his life as a writer, but distils it in a finely crafted manner, refined and shorn of the distracting spelling errors and generic formatting that marred his similar material in books published by the reckless Capall Bann. There’s no sense of re-treading areas already well-travelled, even though the referencing of folklore was something he often did. Instead, like the rituals written specifically for this volume, there’s a feeling of Howard setting out to write something self-contained and true to itself.

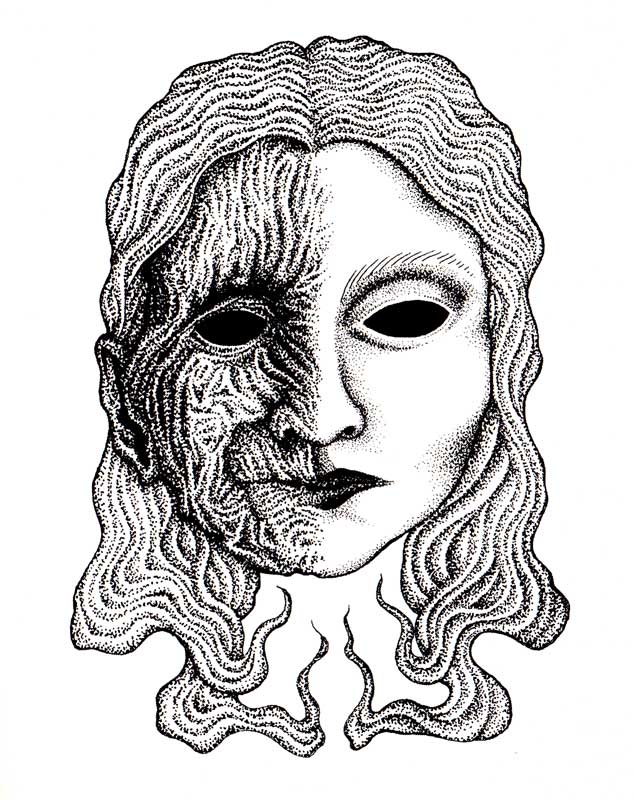

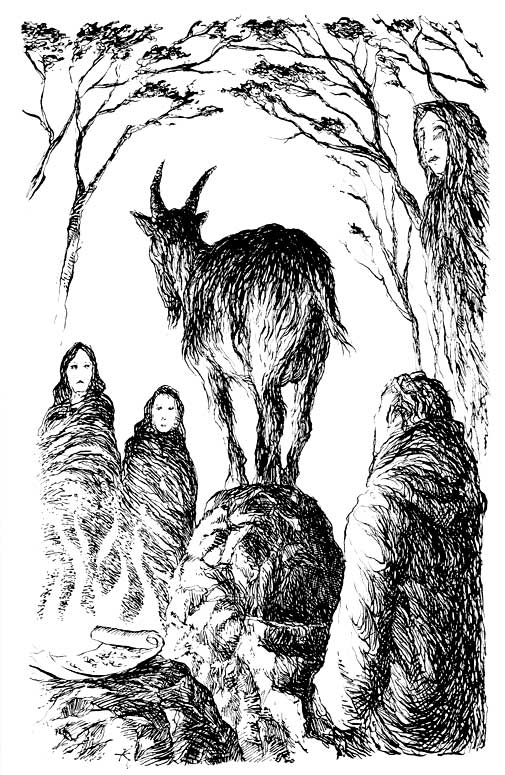

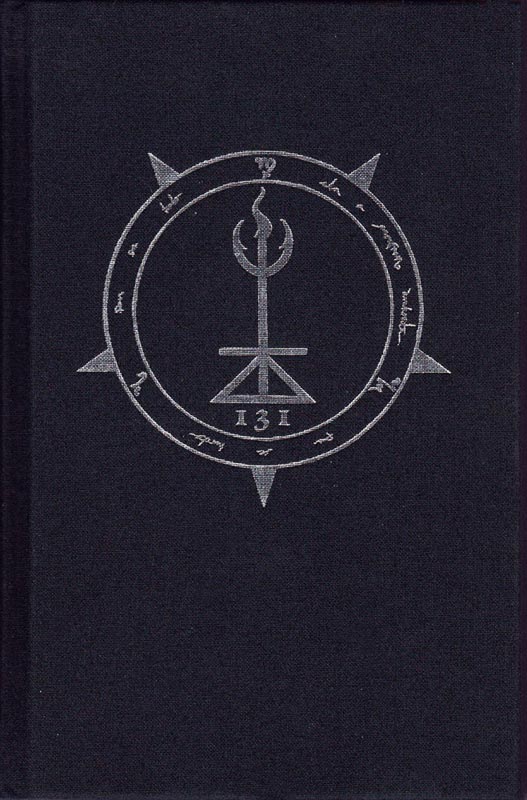

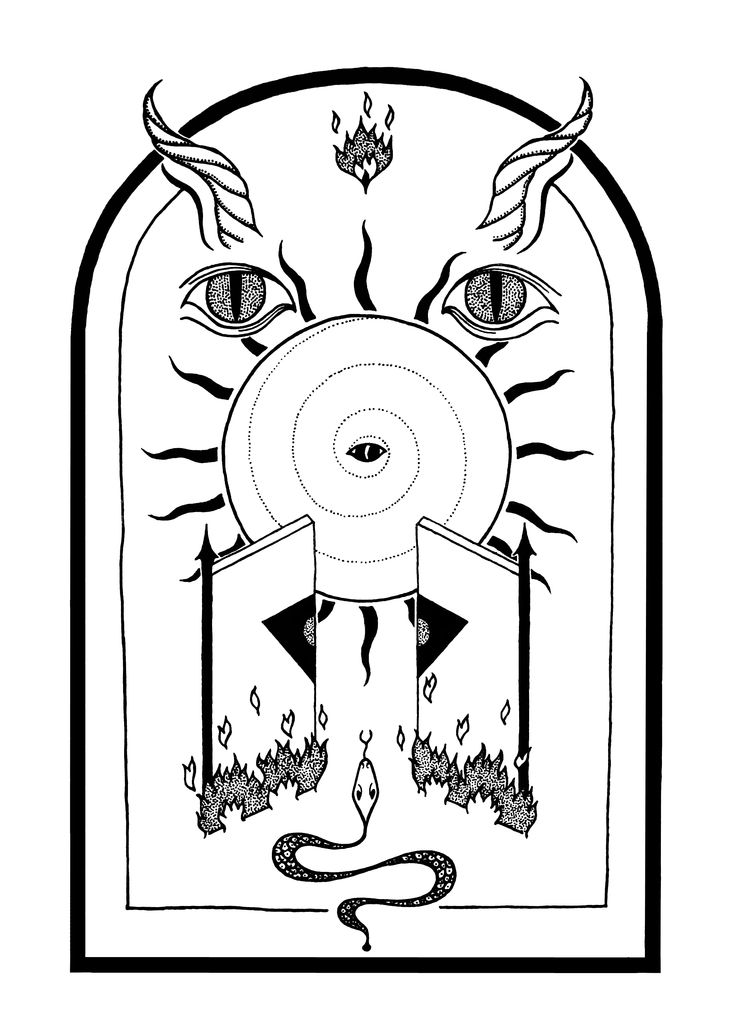

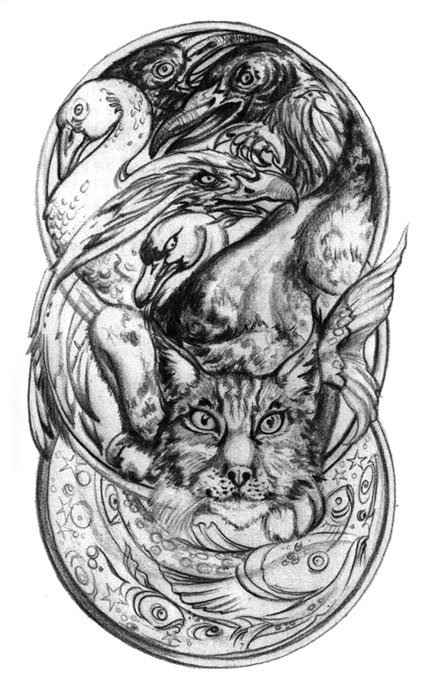

Liber Nox is available as a paperback of 218 perfect bound pages, printed by Lightning Source. The formatting has a confident, effortless style, with the body set in Adobe Caslon at a nice point size with sensible leading; albeit fully justified. Titles (along with the chapter-leading drop caps) are set in the rather lovely Newcomen face, while the subtitles are rendered in the scratchy scripty 1491 Cancelleresca. Liber Nox is illustrated throughout by the black and white illustrations of Gemma Gary, who also provides the stunning image of the horned god on the cover. Her illustrations are often of familiar folkloric images, masks and masques, rendered anew in her stippled style.

Published by Skylight Press. ISBN 978-1-908011-85-5