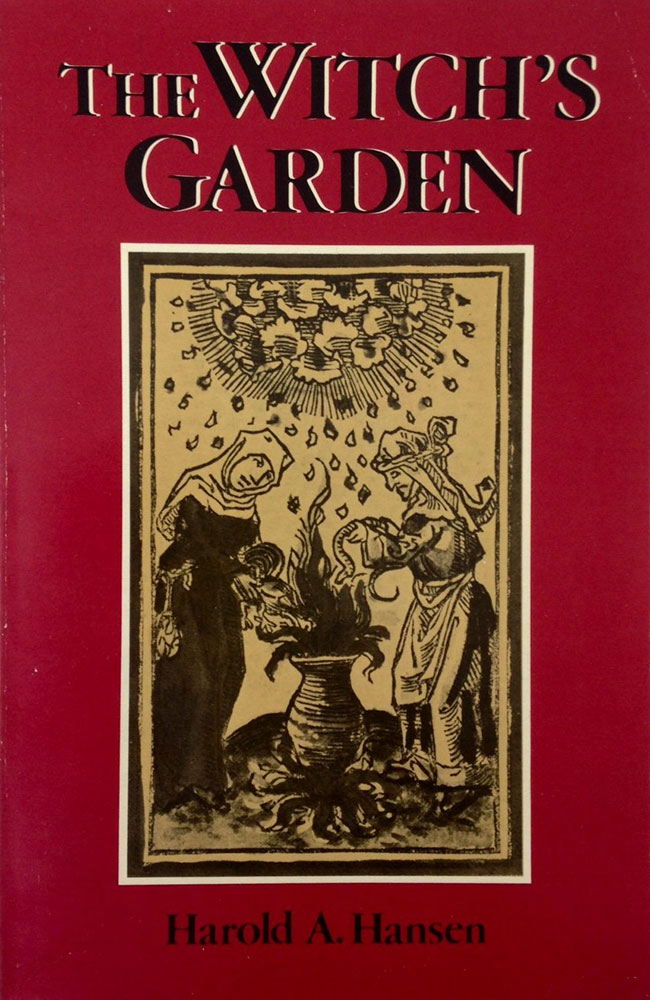

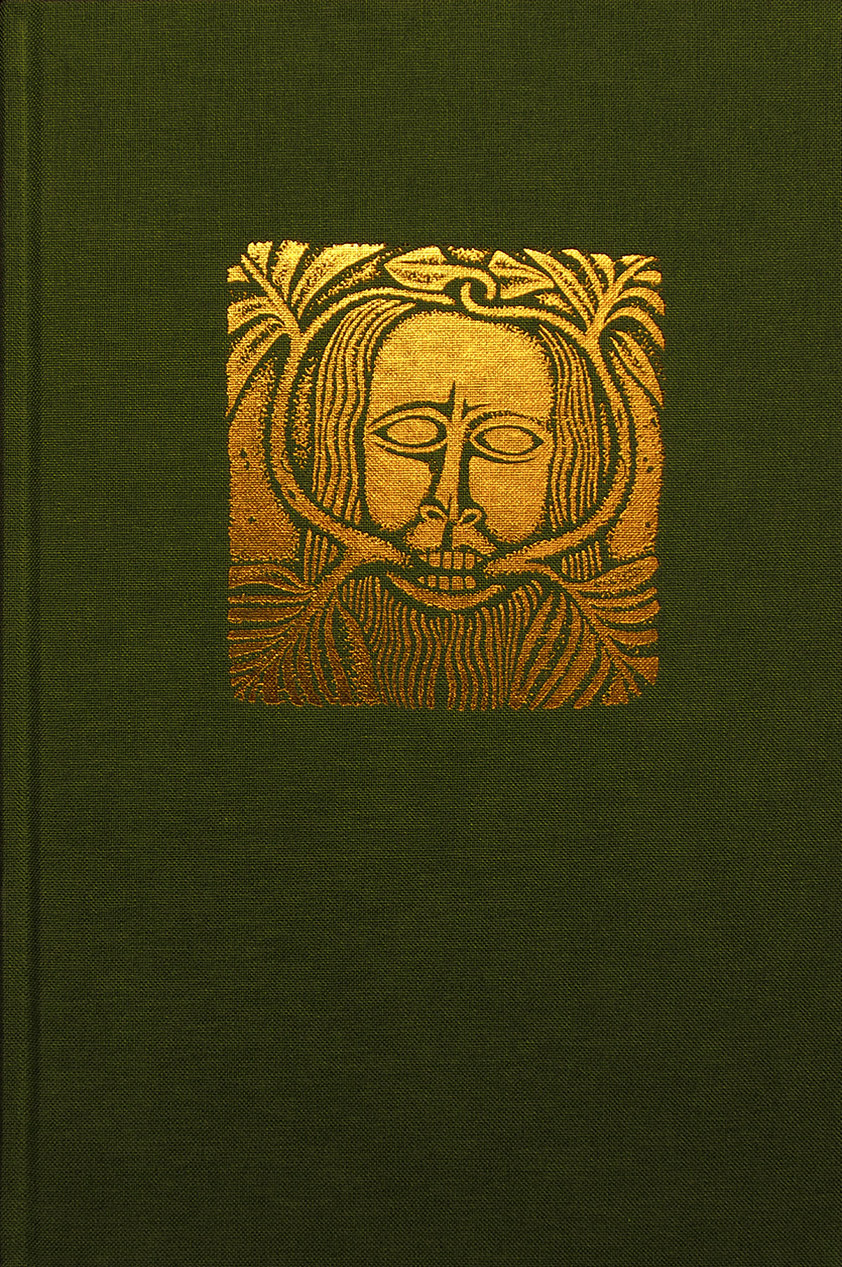

This publication holds a special if dubious honour within the salty halls of Scriptus Recensera, being the first book published by Llewellyn Worldwide (long-time purveyors of lightweight and easily mocked titles) to be reviewed here. While Llewellyn certainly have released some less than rigorous titles over the years, attracting now predictable derision as fluff and other barbs so beloved of serious business occultists, they have, in their time, occasionally published more serious titles, often of the reference variety. This is the case here, with an definitive edition of The Long Lost Friend, an anthology, as the subtitle betrays, of nineteenth century American folk magic.

This publication holds a special if dubious honour within the salty halls of Scriptus Recensera, being the first book published by Llewellyn Worldwide (long-time purveyors of lightweight and easily mocked titles) to be reviewed here. While Llewellyn certainly have released some less than rigorous titles over the years, attracting now predictable derision as fluff and other barbs so beloved of serious business occultists, they have, in their time, occasionally published more serious titles, often of the reference variety. This is the case here, with an definitive edition of The Long Lost Friend, an anthology, as the subtitle betrays, of nineteenth century American folk magic.

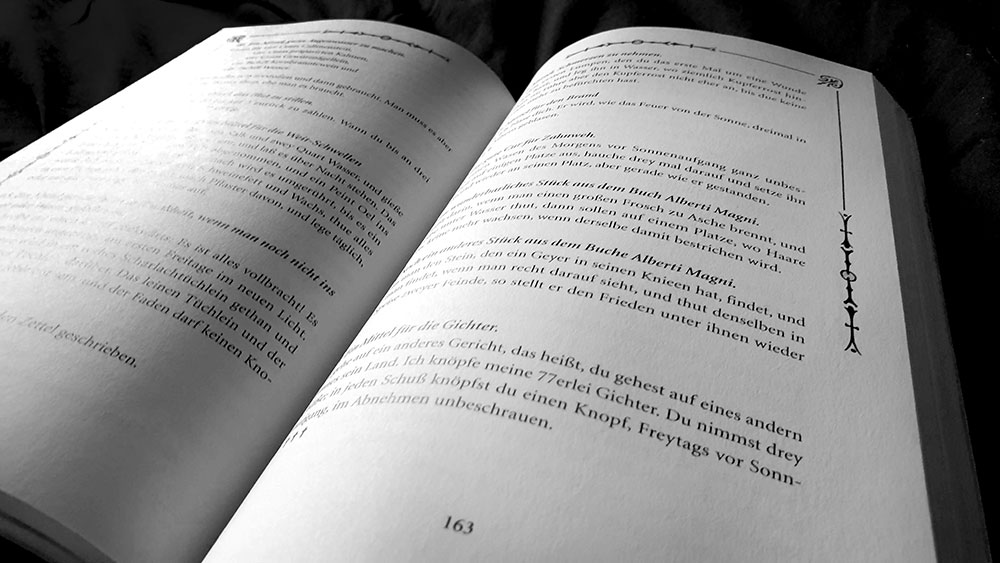

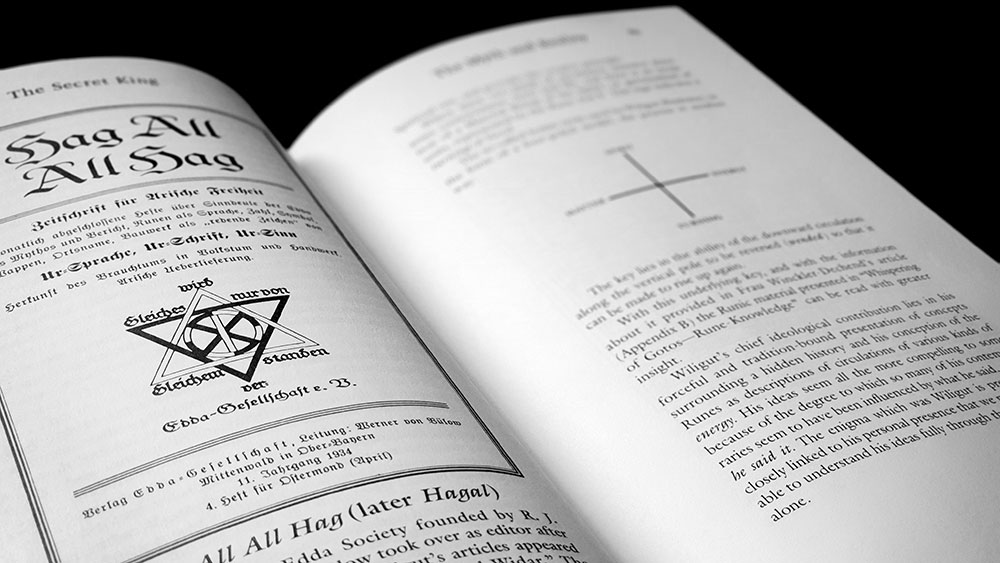

First published in German in 1820 as Der Lange Verborgene Freund (‘The Long-Hidden Friend’) by author and publisher John George Hohman, this work was then released in two English translations, first in 1846 as The Long Secreted Friend or a True and Christian Information for Every Body (in a translation by Hohman himself) and then the second in 1856 as the exhaustively-titled The Long Lost Friend; a Collection of Mysterious and Invaluable Arts and Remedies for Man as well as Animals. Given the inevitably concise nature of a book such as this, running to just 190 often brief charms and spells, it may come as a surprise that this contemporary edition clocks in at almost 300 pages. And it is this length that proves the true value of this edition, with a veritable surfeit of supplementary information, including a series of appendices twice as long as the grimoire itself, as well as Daniel Harms’ extensive introduction and annotations. This point of difference is important because the text itself is in the public domain and is available online as well as in multiple print versions, including a lovely looking, multi-format edition from Troy Books, edited and illustrated by Gemma Gary.

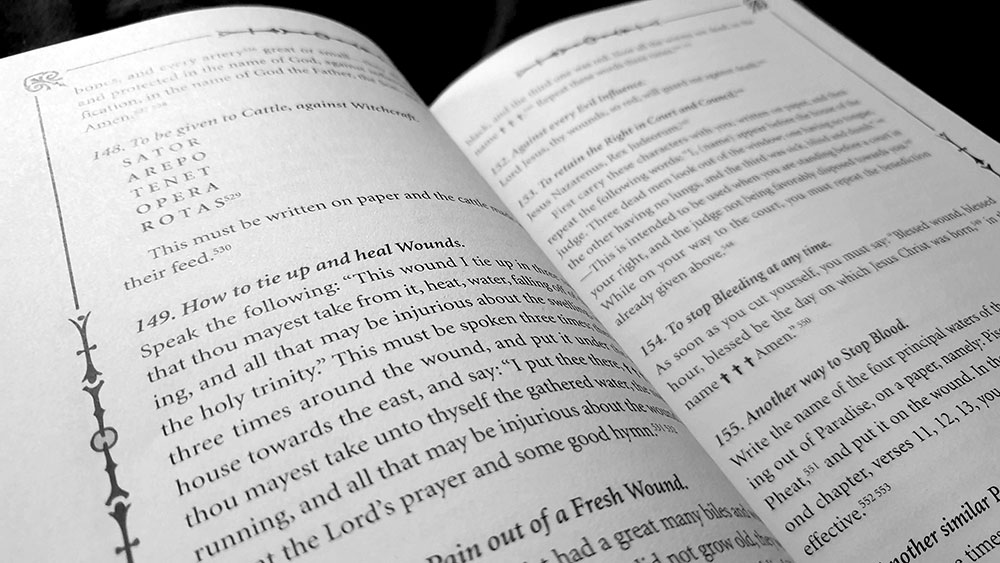

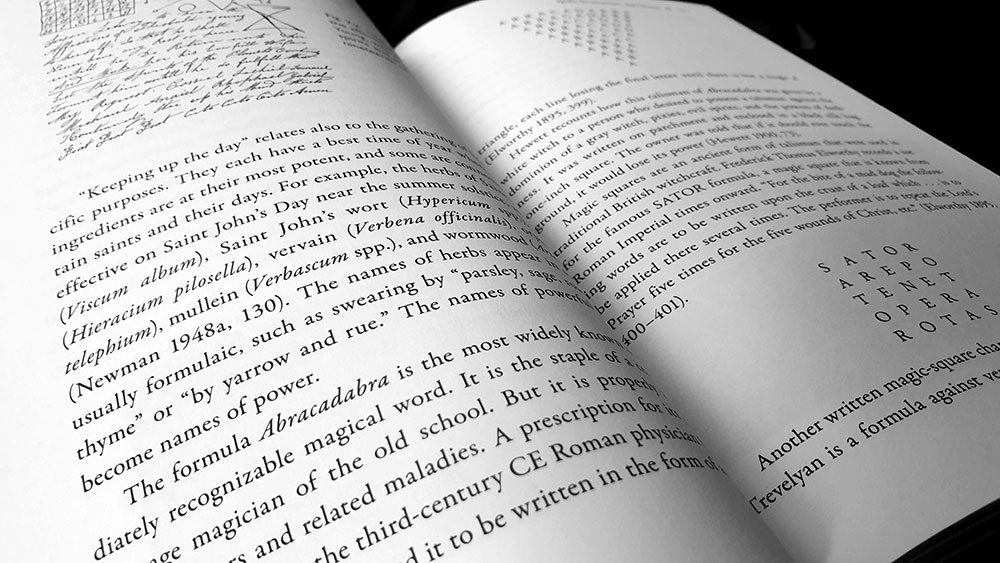

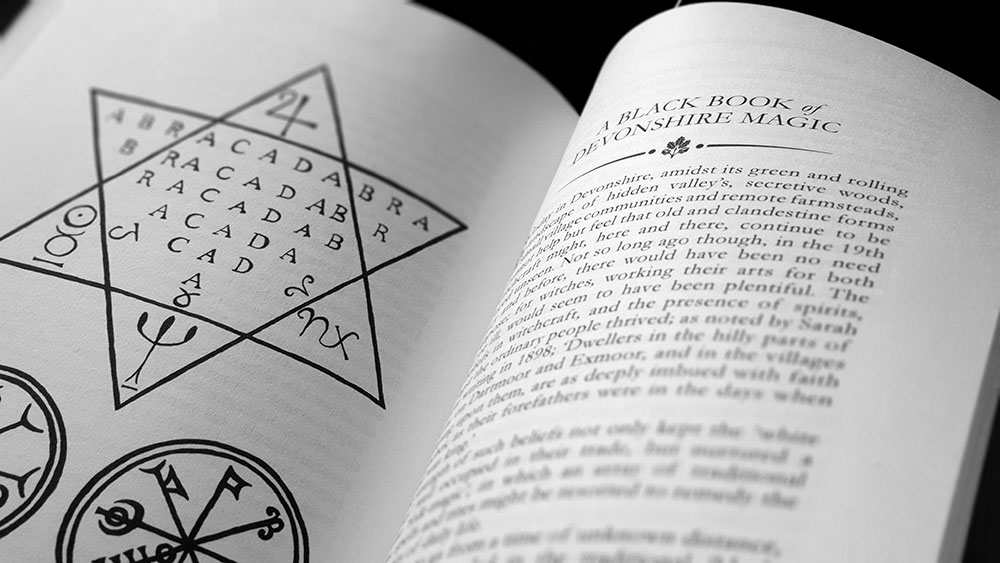

The description of The Long Lost Friend as a grimoire may be a bit of marketing glamour from Llewellyn, as there’s little here that compares it to the classics of the genre: no casting of circles, no summoning of demons, no barbarous names, and no cool-looking sigils. While it might be splitting semantic hairs, a better term might just be a charm book, one that, as Owen Davies notes in his definitive tome Grimoires: A History of Magic Books, ventured only occasionally into grimoire territory. Thus, there is an invocation to the angel Gabriel for assistance in finding iron, ore or water with a wand, and a charm against witchcraft that uses an INRI-based acrostic, but otherwise everything is pretty standard folk magic fare.

In his introduction, Harms provides as detailed a history as possible of the grimoire’s author, John George Hohman, detailing his arrival from Germany and ventures into publishing to alleviate a near persistent risk of poverty; suffice to say, there’s not a lot of spells for money making in this book. Hohman, in his own introduction seems at pains to stress two things about his book: that the book’s spells are not at odds with Christianity, and that their efficacy is well documented and beyond reproach. Despite an earnest, confident swagger, Hohman testifies to the existence of heaven and hell and claims that every wheal or mortification he has banished using the spells documented within the book has been done by the Lord. With a carney’s patter he then rattles off a list of anecdotal success stories, three pages worth, which proves at least one thing, that most of these spells take 24 hours to work. There’s Catherine Meck of Alsace township whose wheal in the eye was healed in little more than 24 hours, Michael Hartman Jr. also of Alsace, whose child was healed of a sore mouth in little more than 24 hours, plus Mr Silvis of Reading whose wheal in the eye was cured in a little more than 24 hours. Eye wheals seem to have been a major cause of concern in Pennsylvania, that and undiagnosed pain which, mercifully, could also be dealt with in little more than 24 hours. Suffice to say, Hohman’s somewhat specious success comes across less convincing to the reader than it apparently did to him.

The spells in The Long Lost Friend are what one would expect of a collection of folk charms: simple, a little bit gross and usually pretty useless. Right out of the gate, the second spell is a disgusting favourite: as a remedy for hysterics or colds, in the evening, whenever you take off your socks, run your fingers between your toes and smell them. “This will certainly effect a cure.” Not sure about that but it will certainly effect something. I think I’ll stick with having a cold, thanks.

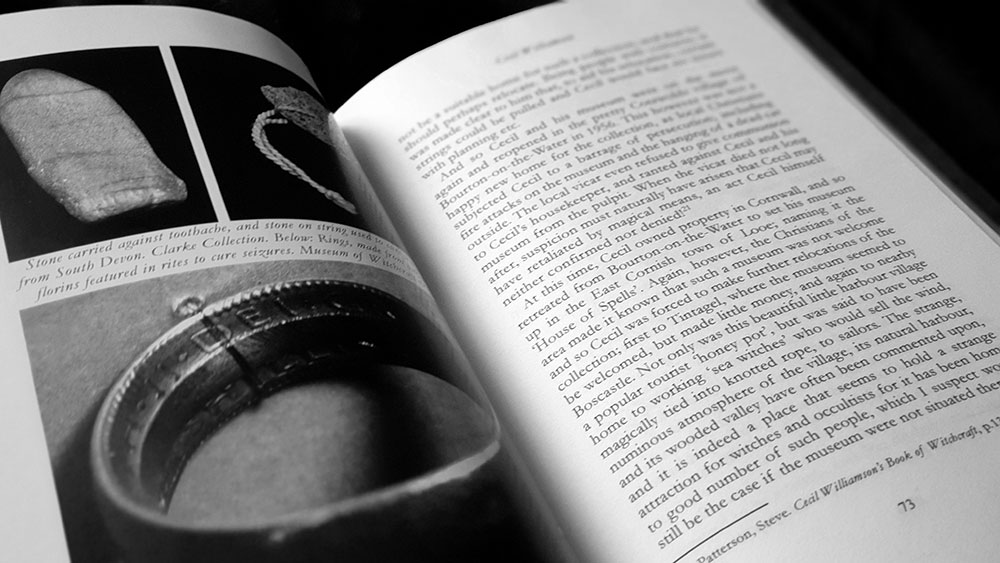

As evidenced by some disappointed reviews on Amazon, if you come here looking for traces of paganism (as all magic is often assumed, without merit, to be) or a practical book of simple commercial spells and love philtres, then you’re going to be disappointed. Obviously, that’s not the point here, and instead The Long Lost Friend is an exhaustive curiosity, valuable for its historical and reference purposes, particularly as an intersection between old and new world magic, but not, indeed, the most dependable of friends, lost or otherwise. That isn’t to say that everything here is entirely useless and like a wrong clock there are cures that hit on some efficacious quality, such as peaches being used to relieve kidney stones, or blue vitriol (copper sulphate) to alleviate toothache. Just don’t expect me to boil a rabbit’s brain and rub it on a child’s teeth when they’re teething, or to imbibe the powder from a burnt hog’s bladder in order to halt incontinence.

Many of the spells and charms specifically situate the relevance of this work in its time, betraying the concerns of the region’s rural habitants beyond eye wheals and random aches. Barking dogs, for example, were a bit of a nuisance, in fact that may be underselling the annoyance somewhat as the methods of dealing with a mere bark seem complicated, not to mention unnecessarily cruel: there’s wearing a dog’s heart on your left side (presumably not from the one that’s barking but that would also be effective), or wearing halves of a barn owl heart under each of your armpits. Said heart and the poor barn owl’s right foot can also be placed on a sleeping person to make them answer anything you ask; perhaps “why do you have bits of an owl on you?” Let it not be said that Pennsylvania spell workers didn’t use the whole of the barn owl.

Not all of the charms here are brutal and scientifically deficient and things do occasionally take a practical turn with, for example, instructions on how to make molasses from pumpkin (so good they were attested to have been mistaken for the real thing by Hohman himself) or how to a make a ‘good beer.’ Then there’s also a recipe for buttermilk pop, a one sentence method of cleaning brass, instructions for making plaster for cracks, and a guide to making glue. All of this highlights the practical, everyday aspect of a book like this, with supernatural charms sitting alongside home tips, thereby coming across like a farmer’s almanac with a little more animal cruelty, rather than a grimoire full of sigils and barbarous names. “So, got any instructions for making toilet soap, Grimorium Verum? Know how to make an excellent liniment, Sworn Book of Honorius? What? No? I’ll stick with my Long Lost Friend then.”

From a religious perspective, the text of the charms and spells here often have a liturgical origin, drawing from the nomenclature and trappings of Catholicism, and giving them something of an exotic twist amongst a predominantly Lutheran and Reformed Church audience. It’s in these cases where the book is at its most magical, with the Virgin Mary and the Trinity being invoked, along with St. Peter and the other occasional saint, including none other than St. Cyprian.

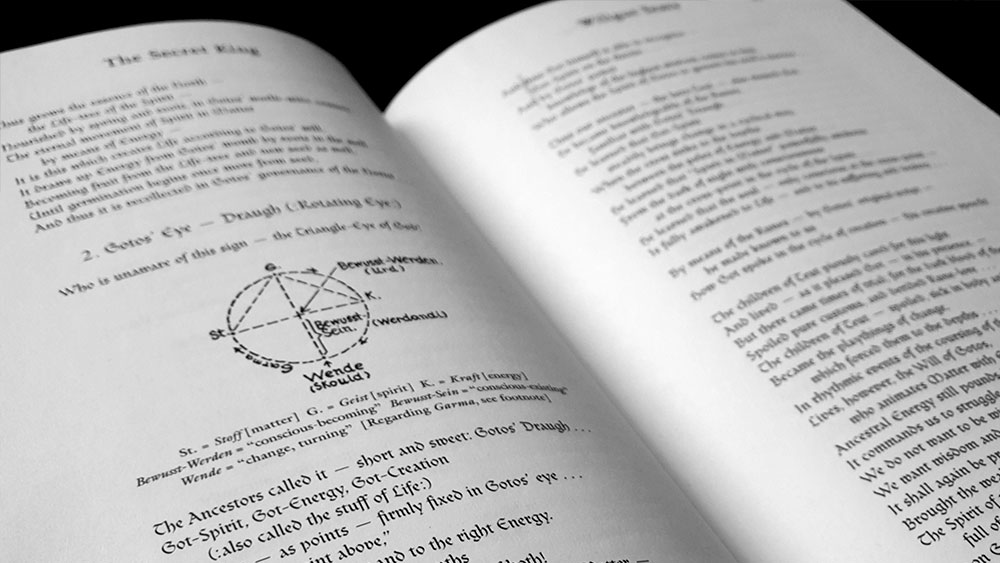

Harms is rigorous, almost relentless, in his annotation of the spells and charms here, sometimes loading up a simple, one sentence charm with as many as three endnotes, resulting in 46 pages of endnotes. Indeed rigour is a key word here, from the thorough introduction, to the endnotes’ attention to minutiae within each charm and spell. Necessitating that a second bookmark be kept towards the end of the book, Harms’ endnotes document the provenance, where known, of each entry, provides a definition for terms unfamiliar to a modern audience, and notes where changes exist between different editions of the book.

With the exception of these several pages of endnotes, for solely English speakers, the book’s use largely comes to an end at page 144, as the remaining half reproduces The Long Lost Friend in its original German, highlighting its value as a reference work.

Published by Llewellyn