The size of the ‘witchcraft’ tag in the column to the right is testament to the popularity of the genre and to the amount of so-themed titles that, through little conscious effort, have ended up crossing the Scriptus Recensera submissions desk and being reviewed. With so many witchcraft books read and reviewed, it is often hard to find a unique selling point, with even areas that were once fairly limited specialities, like Traditional and Luciferian witchcraft, now being represented by a veritable surfeit of titles. Needless to say, if this title from 2008 didn’t have something to offer, it wouldn’t have made its way with such ease to the crowded top of the library pile, and this said ‘something’ is effectively a more Germanic take on witchcraft.

The size of the ‘witchcraft’ tag in the column to the right is testament to the popularity of the genre and to the amount of so-themed titles that, through little conscious effort, have ended up crossing the Scriptus Recensera submissions desk and being reviewed. With so many witchcraft books read and reviewed, it is often hard to find a unique selling point, with even areas that were once fairly limited specialities, like Traditional and Luciferian witchcraft, now being represented by a veritable surfeit of titles. Needless to say, if this title from 2008 didn’t have something to offer, it wouldn’t have made its way with such ease to the crowded top of the library pile, and this said ‘something’ is effectively a more Germanic take on witchcraft.

Eric De Vries’ key premise can be summarised in one thought, the roots of witchcraft, and in particular the figure of the Witch Goddess, are in a shamanic take on Germanic myth and folklore, and that the oft-touted idea of Celtic origins or influence is overstated. Indeed, throughout this work, De Vries uses the details found in Norse mythology to flesh out the more vague descriptions of witch trials and faery lore. With this, and revealing this reviewer’s biases, comes a pleasant focus on things Helish and chthonic, with De Vries following in the vein of some incarnations of Traditional Witchcraft, particularly those inclined towards the approach of Robert Cochrane, that centre on the idea of a Pale Goddess of Death and the Underworld who combines elements of both Hela and Holda.

De Vries writes in a largely informal and conversational style that is fairly loose, his editorial voice jumping around with equal parts enthusiasm and earnestness, and with both characteristics contributing to the occasional jibe at Wiccans and other people he disagrees with. Throughout Hedge-Rider, De Vries gives often somewhat contemporary interpretations and musing on metaphysical themes, rather than just presenting the symbolism as self-evident. This aligns with his informal tone, having, like Jan Fries, the tendency to try and demystify what he’s presenting, rather than layering on the obfuscation.

After an introduction to the concept of the hedgewitch, the first chapter proves to be indicative of De Vries’ approach here, detailing first the conception of the underworld and Hela found in Norse myth, and then relating both of these to continental tales of Holda and Holle, As the final step in this puzzle, De Vries then focuses on Holle’s association with witches and in particular the wild hunt, showing that she was both a goddess of life and death, of night and day.

From the witch goddess, De Vries turns to a male counterpart, the black god, whom he primarily identifies with Óðinn/Woden, before proceeding at a brisk pace into chapters on various practical tools and applications. This begins with a consideration of steads and stangs as vehicles for transvection and then evolves into various methods of invoking trance, including the use of wine and entheogens. De Vries seems to be an enthusiastic advocate of the latter, though he only vouches for mugwort, wormwood, sweet flag and passionflower (all with the necessary caveats about careful use), and balks at the use of any mushroom whatsoever, since, as he definitively states, “you’ll only end up hurt or in hospital.”

The rest of Hedge-Rider continues downwards as it were, providing further tools and methods of travelling to the underworld, drawing on the idea of the fetch and fylgia, as well as ideas of werewolf transformation, each time returning to the themes of witchcraft and then informing them with details drawn from Norse mythology. This is a mixture of the practical and the historical, with De Vries providing techniques along the way but always including them broadly within the body of the text, never as a set of rigid instructions or recipes. The reader is thus introduced to a variety of themes and tools, but nothing that feels dogmatic; though this may not be too appealing for those who prefer instruction and structure.

In the penultimate chapter, the journey reaches its end in the underworld but this isn’t necessarily one in which Hela or any other queen of the underworld is directly encountered. Instead, De Vries turns to the model of the hieros gamos, using Svipdagr and Menglöð, and Freyr and Gerðr as examples of the hero who journeys into the underworld for the love of an otherworldly maiden. This he then brings back to witchcraft via the idea of the demon lover, such as the incubus or succubus, but it’s a brief chapter that feels like the ideas are not fully explored.

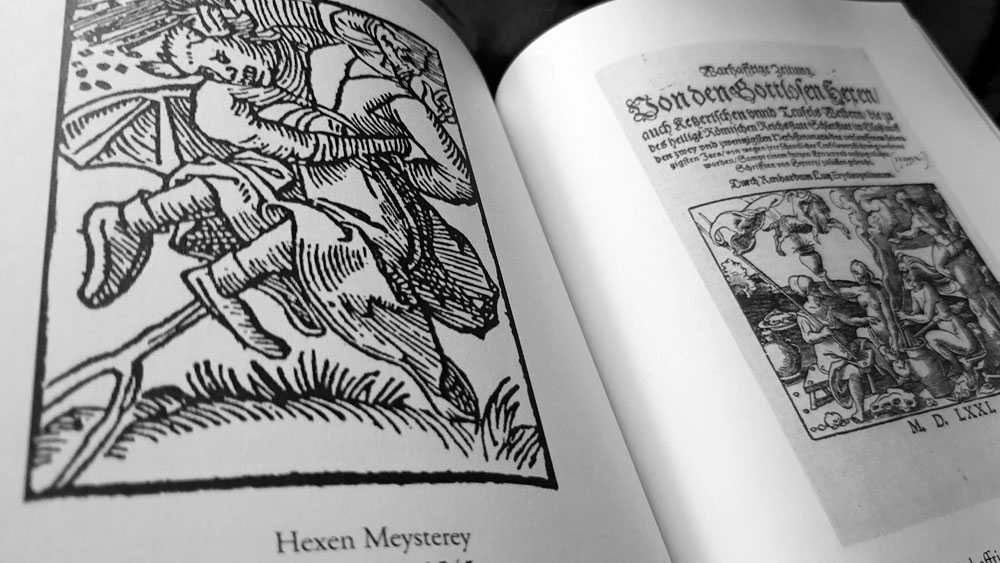

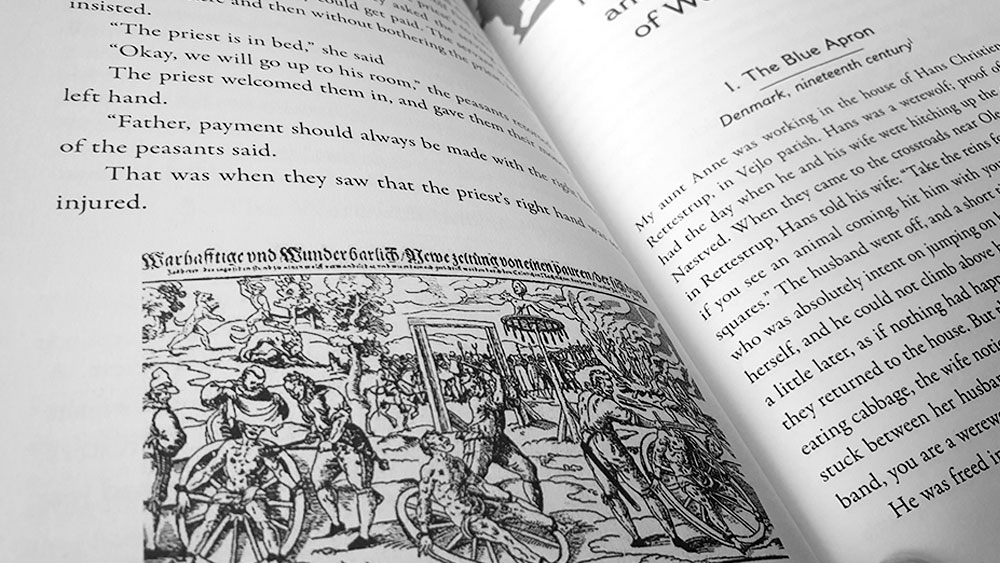

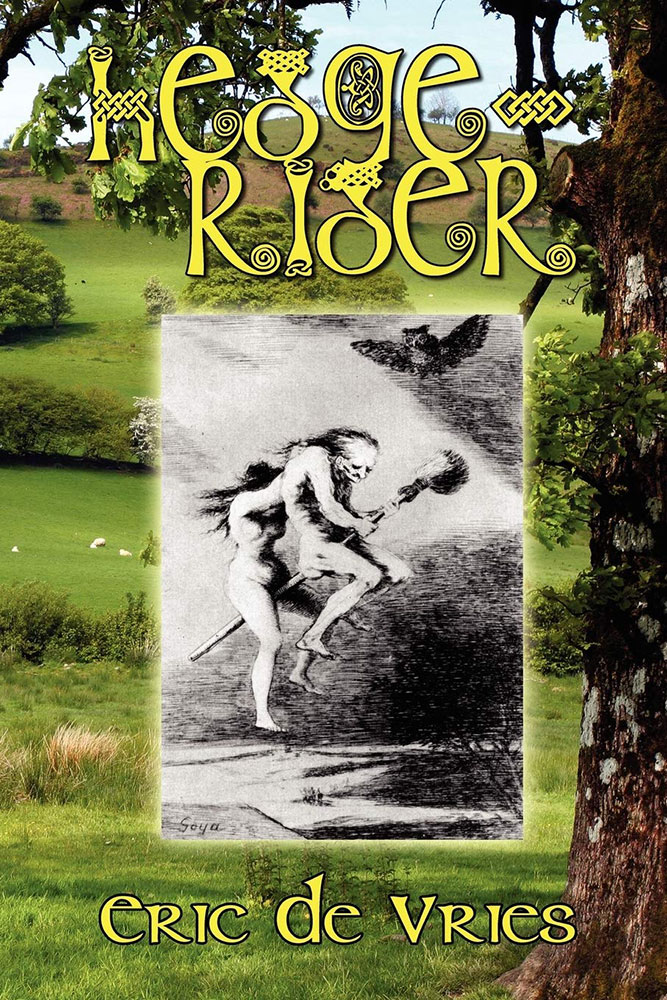

Finally, De Vries presents a few pages in summary, followed by musings on lessons learnt and how these can be applied in the everyday. And with that, Hedge-Rider concludes rather quickly, with its large point size meaning you can breeze through the 139 pages that make up its content proper. This is then padded out to 194 pages with an index, a collection of reproduction of many of the classic woodcuts of witchcraft, a book hoard, a reproduction of Grógaldr, and an extensive but not entirely necessary glossary of terms in which even witch apparently needed to be defined.

Despite his heart being in the right places, there are many problems with the presentation of the material in Hedge-Rider. Too often, De Vries inexplicably begins sentences and even paragraphs with filler words, particularly minor crimes like ‘however’ and ‘also.’ But the strangest opener is ‘actually’ with which, apropos of nothing, he often begins whole paragraphs, seemingly responding to a prior clause that was never argued. This erratic authorial voice can make the copy feel like a first pass, an ebullient but unedited mind dump, and this impression is compounded by the sloppy editing, with a peppering of spelling mistakes, switched homonyms and the occasional malapropism; something that is on show in the book’s very first sentence when De Vries says “Often you here so called ‘Wiccans’ and ‘Pagans’ claim that they are witches.” Poor Baldr fares even worse though, and a lack of proofing renders him as Bladr several times, creating quite the visual image when his death during the gods’ deadly game is mentioned. One could make some allowances for all of this if, as one assumes, De Vries is not a native English speaker, in which case the fault lies more with the publishers, Pendraig, whose best practice should have included a cursory proof and a spell check of at least the first paragraph, if not more.

Along with the sloppy and inconsistent spelling, there are the occasional equally sloppy moments of fact checking. Nothing is ever directly cited, leading you down your own avenues of fact checking, and while there appears to be no malice, there are things that seem to have got muddled. An account from Herodotus is merged, uncredited, with one from Pliny to create a single composite that draws details from two sides of the continent. Similarly, as so often seems to happen, the cast in the events leading up to the death of Baldr are conflated, and while usually the casual retelling in error mistakes Freyja for Frigg, here they’ve gone one step further and it’s her brother Freyr who asks all creatures in the world not to harm Baldr.

With all that said, Hedge-Rider is a worthy read that has much to recommend it, with caveats. Its overall argument and themes are solid, but it is by no means authoritative, with the lack of references and the brisk pace meaning that the reader may need to do their own work tracking down the sources and seeing how it all stacks up.

Published by Pendraig