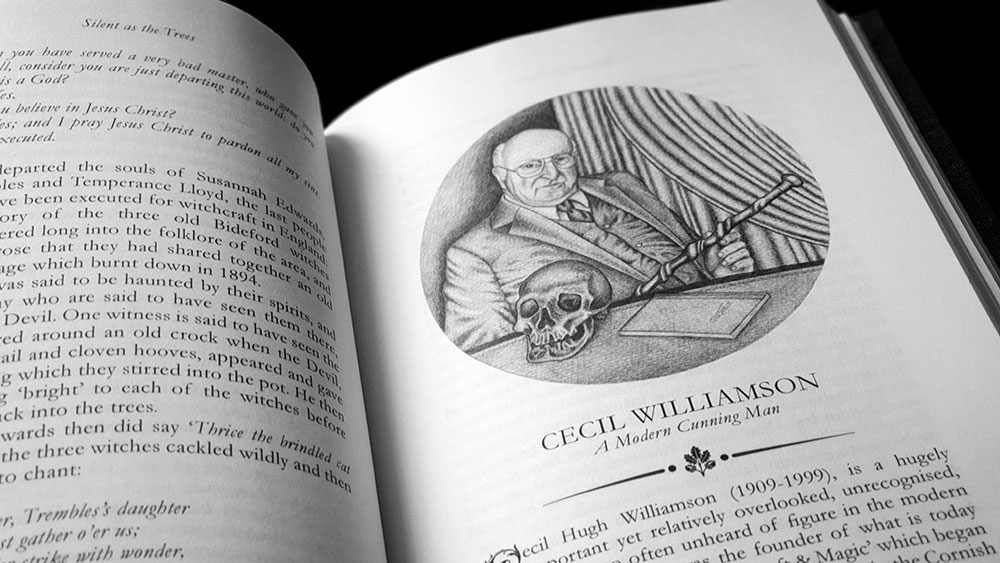

Subtitled Plant Consciousness Healing & Natural Magic Practices, Emma Farrell’s Journeys with Plant Spirits is a book that is light on the plants and heavy on the ‘consciousness,’ in the most excoriable form of the term. The book shares its name with an online course that Farrell runs for a mere £260; a price that generously includes a free copy of this book, score! As one would expect, the course mirrors the contents of this book with much talk of energy fields, consciousness and personal psychopspiritual (sic) healing.

Subtitled Plant Consciousness Healing & Natural Magic Practices, Emma Farrell’s Journeys with Plant Spirits is a book that is light on the plants and heavy on the ‘consciousness,’ in the most excoriable form of the term. The book shares its name with an online course that Farrell runs for a mere £260; a price that generously includes a free copy of this book, score! As one would expect, the course mirrors the contents of this book with much talk of energy fields, consciousness and personal psychopspiritual (sic) healing.

Farrell is described as a plant spirit healer, a geomancer, a shamanic teacher, an apothecary of plant spirit medicine, the runner of a school of warrior healers (a handy class in a MMORPG, to be sure), a cofounder of the self-described “ground-breaking” Plant Consciousness event in London, the recipient of a mere two-year master’s degree, and someone who has been initiated into ancient magical practices of both the British Isles and the Ecuadorian Amazon. That’s a lot of things. Farrell also describes herself as a lineage holder of the White Serpent teachings, the system of one David Leesley, a mortician based on the Isle of Man who also claims to be a Vanuatuan High Chief whose arrival on the island of Tanna was long foretold by its so-called cargo cults (a bid for colonial prophetic glory that, surprisingly, is not unique for a certain class of bearded white men, as documented in Jon Tonk’s recent book The Men Who Would Be King).

Farrell divides this work into two sections, the theoretical Entering the World of Plant Spirit Healing and the slightly more practical Thirteen Plants and Tree Spirits. The first section shows one of the problems with Journeys with Plant Spirits, the fluff, with a constant churn of metaphysical speculation in which so much is written but little is said. This is particularly true of the preponderance of unverifiable and glib statements that are de rigueur in new age writing and apparently don’t require any proof, other than an unctuous tone. All of which frankly feel a little dated in their fear-inculcating paranoia: television is the real hallucinogen used by “the authorities” to brainwash you, man; the symptoms of any disease come not from the disease itself but as the result of our experiences in life; toxicity surrounds us on ever side like predacious demons to the medieval mind; education is a meanie, and water has memory. Indeed, fairly generic water woo plays a significant role here, and leads to several descents into pseudo-scientific quackery, such as the bizarre statement, uttered with all the unwarranted certainty but lack of referencing that one would expect, that the molecules in tap water and bottled water are ‘shattered,’ whatever that means, and that this unstructured water is hard for the body to absorb. Quite why or how this has happened isn’t explained (why would you need to anyway, given that it’s apparently self-evident that modern-life=bad), but then bizarrely, Farrell says that the water in our bodies is the same water that is in the sea and clouds, which would surely mean that all water everywhere is broken, whether it comes out of a tap, bottle, urinary tract or refreshing mountain stream. Oh noes, we is doomed.

In concert with this wooliness is how Farrell’s grab-bag of credentials comes through within the pages of this book, with the text presenting information as a myriad of little bits without any depth or breadth. Various concepts are referenced but often with only a superficial glancing blow, lest anything be said in detail that could be easily queried or found contrary to the general narrative that is being promoted. Thus, there is talk of medicine wheels but any association with Native American expertise is fleeting and instead only the nomenclature is used with talk of a “Celtic medicine wheel” and the “tradition of medicine wheels” in the British Isle. There’s a bit of Tibetan Buddhism here, a little Chinese medicine there, and a mention of a Kichwa shaman that Farrell knows who calls earth a ‘prison planet.’ There are appeals to authority by quoting the pseudoscience of the Hearthmath Institute and, of course, there’s the de rigueur New Age references to misunderstood quantum physics as something that is ‘breaking down the barriers between science and spirituality.’ Naturally, the latter comes on the heels of a moan about how the scientific method is all about rules, man, and how all that analysis and measuring and verifiable results is such a bummer, dude.

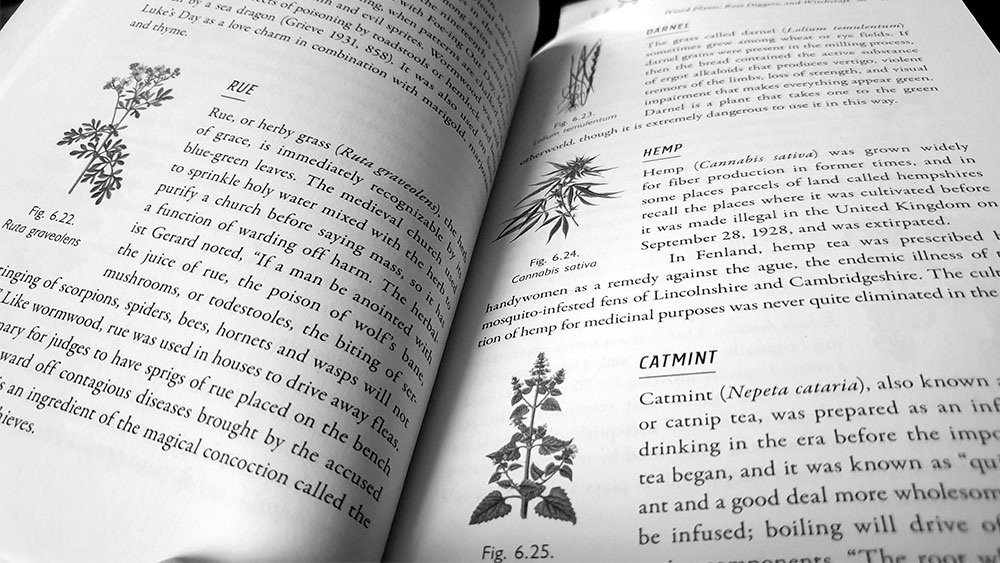

It takes 128 pages of new age speculation and metaphysical truisms to get to the actual plant spirits of the title. Farrell has chosen thirteen spirits, a combination of herbs, weeds, shrubs and trees, featuring mugwort, oak, hawthorn, nettle, dandelion, alder, lady’s mantle, rosemary, fireweed, wormwood, angelica, elder and yew. Each plant receives its own chapter, prefaced with little hand drawn illustrations by UK-based artist Edward Foster, and featuring a multi-page exploration of both plant and spirit, followed by examples of practical application such as mediations and less frequently, guided meditations. As is to be expected, given the precedent set in the first half of this book, things get pretty fast and loose with facts, along with the insertion of a raft of new age terms like energy fields, harmonic resonances and psychic hygiene, all shot through with paranoid ideas about toxic entities that might sneak in through negative emotions. By now, the latter is par for the course, and so what really grates is the lack of rigour in what little historical or quantifiable information there is about each plant. Mugwort is “known as the queen of herbs or the witches’ first herb,” but no, it’s not, it just isn’t. Then there’s the claim that “in the mythology of the British Isles, fire is Freyja, the goddess of the three worlds who carries the impetus for the Great Web to manifest,” which, whatever the hel that is all meant to mean, is a yeah, um, no to that one too. And then there’s the idea that the lung disease and addiction associated with the smoking of tobacco only exists because of the Western commercialisation of the plant, and not because, you know, smoke is carcinogenic and nicotine is a highly addictive alkaloid.

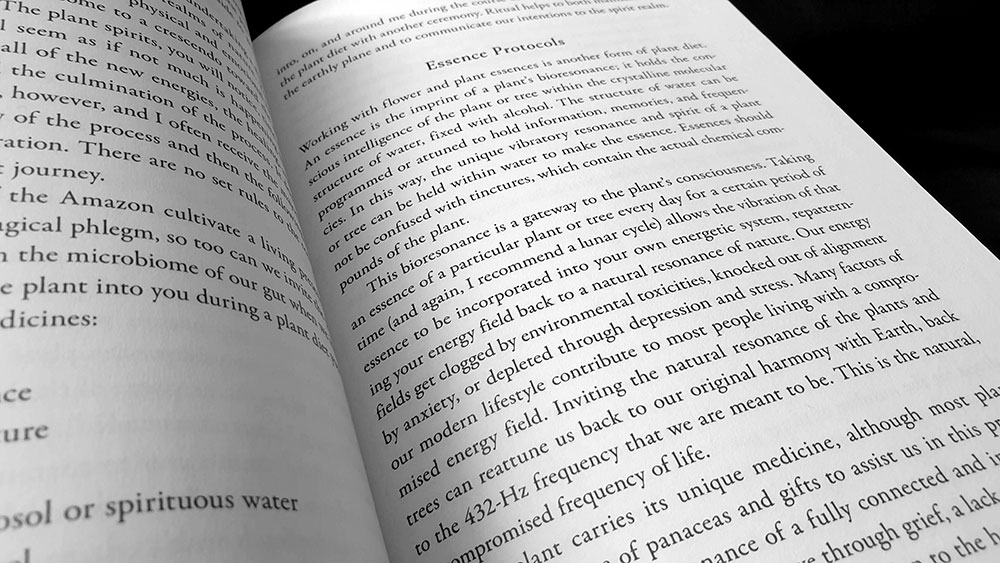

Thus, there’s not actually much that’s tangible in the discussion of each of these plants, with the metaphysical and theoretical dominating the discussion, empiricism be damned. As one would expect, then, there’s very little in the way of specifically plant-related referencing, with the most, which really isn’t much, coming from Dale Pendell and Scott Cunningham, who are cited less than the likes of Rudolf Steiner and Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche. One could argue that this isn’t much of a problem as there’s relatively little practical application given for working with the actual physical plants, with the focus being on the spiritual rather than the botanical. So there’s more time being spent with the spirit of the plant; or at least the spirit as defined by Farrell, because the way in which some of these spirits concern themselves with particularly New Age visions of healthcare would make them unfamiliar to anyone from previous centuries. Even the idea of plant essences which can be taken orally, and which one would imagine involve distilling a plant’s chemical properties into a solution, turn out to contain only the ‘bioresonance’ of the plant spirit, meaning that it “holds the conscious intelligence of the plant or tree within the crystalline structure of water, fixed with alcohol,” which just sounds horrific. So yes, without the nasty chemical compounds of the plant, these essences have done the impossible which is to be even less effective than the watered down remedies of homeopathy.

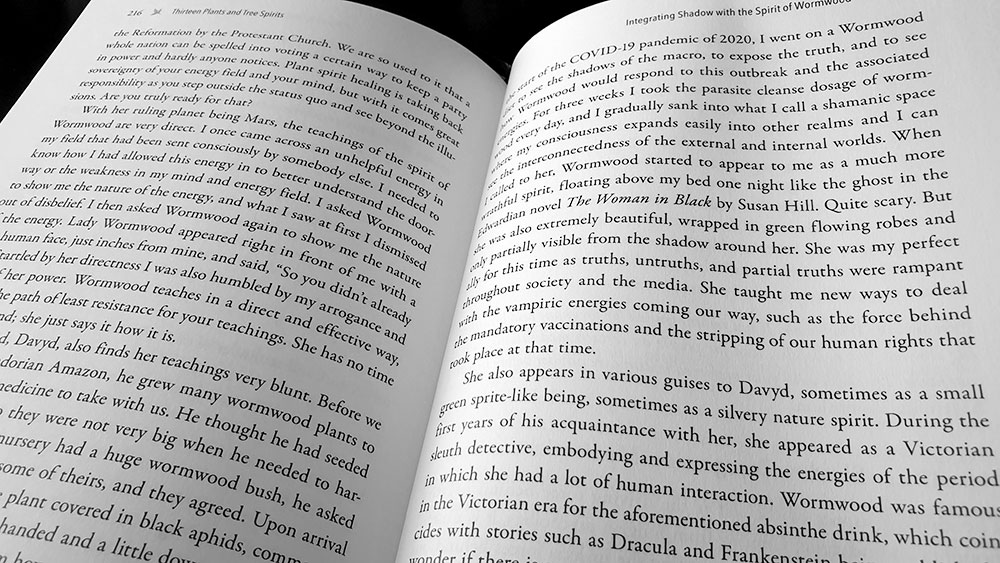

In the end, despite the patina of positivity and good vibes only, Journeys with Plant Spirits comes across as a profoundly negative book, promoting a paranoid and fear-based world view in which unspecified toxins and parasites, both psychic and material, assail us at every turn. A lapsarian world in which everything is broken by an insidious, oppressive and even predatory modernity. Indeed, it’s all rather reactionary, like a New Age Evola setting itself against the modern world™, while the world that is preferable is comparable to a medieval Christian one in which superstition is rife and science, medicine and education is suspect. A world in which delusional parasitosis is rampant and there’s an assumption that these ‘toxins’ will perpetually infect you. That like medieval demons, these anthropomorphised predators can be responsible for anything and everything. Keeping things current, this attitude also bleeds into discussions of the COVID19 pandemic, which unsurprisingly features some paranoid hot takes, with Farrell talking ominously of uncovering truth and of vampiric energies, the dark forces behind vaccine mandates that want to take our freedoms and human rights. Ermahgerd!

Journeys with Plant Spirits runs to 270 pages but, with its metaphysical churn and constant barrage of entirely speculative ideas, feels longer. Text design and layout is by Victoria Bowman, with the body set in Garamond and Hermann as a display face.

Published by Bear & Company