This anthology, edited by Eva Elm and Nicole Hartmann, is the 54th volume in the Transformationen der Antike series, produced by the Collaborative Research Centre’s Transformations of Antiquity project and Humboldt University of Berlin’s August Boeckh Centre of Antiquity. It considers the myriad way in which demons were perceived in late antiquity, drawing variously from spells, apocalypses, martyrdom literature and hagiography to show how this perception was moulded, as anything is, by context both cultural and religious, and considers the specific influence of literary genres on this. The eight articles that are presented here originated from a conference that took place in Berlin in November 2015, with the slightly different title of The Perception of Demons in Different Literary Genres in Late Antiquity, and reveal a variety of voices with different approaches.

This anthology, edited by Eva Elm and Nicole Hartmann, is the 54th volume in the Transformationen der Antike series, produced by the Collaborative Research Centre’s Transformations of Antiquity project and Humboldt University of Berlin’s August Boeckh Centre of Antiquity. It considers the myriad way in which demons were perceived in late antiquity, drawing variously from spells, apocalypses, martyrdom literature and hagiography to show how this perception was moulded, as anything is, by context both cultural and religious, and considers the specific influence of literary genres on this. The eight articles that are presented here originated from a conference that took place in Berlin in November 2015, with the slightly different title of The Perception of Demons in Different Literary Genres in Late Antiquity, and reveal a variety of voices with different approaches.

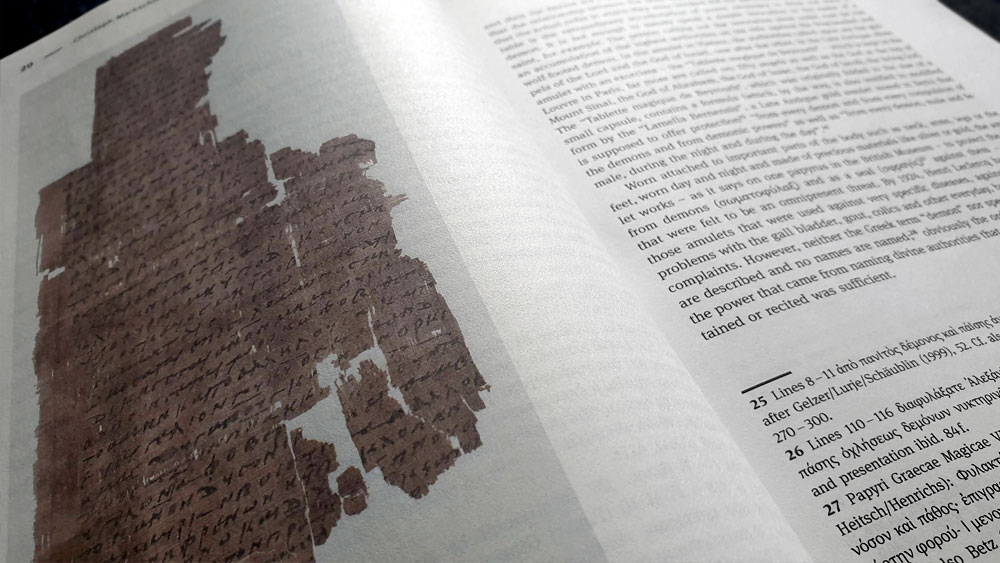

The first four papers in Demons in Late Antiquity focus on the rendering of demons in a variety of genres, including magical amulets, apocalypses and the Vetus Latina (the earliest Latin translations of the Gospels), while the four remaining papers address how the theme appears specifically in late antique hagiography. The intersection between demons, disease and cultural influences is a focus of the first two entries, with Christoph Markschies considering the transformation of pagan concepts of demons to Christian ones on apotropaic talismans, while Annette Weissenrieder’s Disease and Healing in a Changing World concerns itself with the exorcisms performed by Jesus as recorded in the Vetus Latina, in which then contemporary Roman medical ideas inform the narrative. Markschies provides examples of the overlap between pagan and Christian ideas of demons, drawing attention to how in his dialogue Theophrastus, the fifth century Neo-Platonic philosopher and convert to Christianity, Aeneas of Gaza, talks of the airy materiality of demons, ideas that had precedent two centuries earlier in the work of another Neoplatonist, Porphyry. A similar overlap occurs in the work of the presumed-Christian philosopher Calcidius whose fourth century translation into Latin of Plato’s Timaeus includes, as part of his commentary, an excursus on demonology, describing demons as ‘associates of the enemy power,’ a phrase that can be traced back to Porphyry as well. Weissenrieder’s essay, meanwhile, focuses heavily on technical etymology, highlighting difference between the Afra versions of the gospel and the European Vetus Latina versions. By deep-diving into the intricacies of language and the terms used, Weissenrieder argues that the latter texts present a more pragmatic and medical view of the process of exorcism, in which Jesus removes the plague of illness, rather than a plague of demons and unclean spirits. A similar exploration of language at a technical level is found in The Ambiguity of the Devil, in which Nienke Vos employs a discourse-linguistic analysis to focus on the appearance of the devil in Sulpicius Severus’ Life of St. Martin.

Editor Nicole Hartmann’s On Demons in Early Martyrology is not so much about demons but rather a lack of demons, arguing that they feature little in early martyrology. She shows how despite the unquestioned belief then current in a variety of unseen spirits that surrounded the faithful in the everyday, they, and in particular daimones, play little active role in early martyrdom accounts; This early martyrology had little impact in the shaping of Christian demonology, and indeed, later stories of martyrs reflected this evolution, with a reversal in which less focus was placed on the martyrdom itself, and more on contests of power between martyrs and adversarial, malevolent spirits. It is this later period that is addressed in Robert Wi?niewski’s Demons in Early Latin Hagiography, in which he draws specifically on Athanasius’ Life of Antony, Paulinus’ Life of Ambrose, Jerome’s Life of Hilarion and Sulpicius Severus’ Life of St. Martin; the latter two of which are also dealt with individually within this volume by Eva Elm and Nienke Vos respectively. Wi?niewski provides a wide ranging survey of the role of demons in such literature and draws attention to the fact that encounters with demons occur more frequently in the lives of monks than those of bishops, with spiritual combat and the fight against temptation often being quintessential to a monk’s monastic and eremophilous existence, whereas the ecclesiastical life didn’t quite present the same opportunities for interaction with the demonic.

Editor Eva Elm’s consideration of demons in Jerome’s Life of Hilarion is titled Hilarion and the Bactrian Camel and focuses rather less than one might expect, given its titular prominence, on said rabid camel, which appears only in passing references to its exorcism by Hilarion. Instead, Elms presents a thorough account of Hilarion’s life and interaction with demons, including a significant, and ever-so-slightly diverting, preamble discussing his appearance in Gustave Flaubert’s 1874 novel The Temptation of St. Anthony, in which he acts as an adversarial figure attempting to sway his mentor from the monastic life.

Perhaps the most intriguing exploration of this book’s themes is found in Emmanouela Grypeou’s Demons of the Underworld in the Christian Literature of Antiquity, though the demons concerned here are actually punishing angels. Grypeou suggests that later fifth century images of demons as infernal administrators of punishment were informed by earlier themes of angels, not fallen and still aligned with heaven, acting as arbiters of divine justice within Hell itself. She focuses little on transitional examples that might confirm this supposition and instead provides a thorough documentation from a variety of texts of various punitive angeli Tartarum; texts in which they along with personified figures associated with death effectively constituted a ‘mortuary pantheon’ for Late Antique Christianity. Grypeou focuses specifically on second and third century Christian apocalyptic texts such as the Hellenic-influenced Apocalypse of Peter and the Apocalypse of Paul. Both apocalypses mention several hell-bound angels who administer punishments, as well the angel Temelouchos, a figure who appears here as a benign guardian of the victims of infanticide but who in later works, such as the First Apocalypse of John, also becomes a divine arbiter dispensing specifically igneous punishments. Grypeou acknowledges the precedent of tormenting angels in early Jewish apocalyptic texts, such as the Parables of Enoch, the Second Apocalypse of Enoch and the Apocalypse of Zephaniah, and also documents significant examples in later Coptic literature, where the angelic demons of Amente are often thought to be evidence of the survival of ancient Egyptian eschatological ideas.

Save for an epilogue by Jan. N. Bremmer, Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe brings this volume to its conclusion with Demon Speech in Hagiography and Hymnography, in which she exhaustively covers various examples of the speech of demons and their characteristics. She contrasts the utterances of demonic actors in late antique saints’ lives with Syriac and Greek catechetical hymns, such as Ephrem’s Nisibene Hymns, in which infernal beings are given voice as characters in an instructional narrative.

In all, Demons in Late Antiquity is an interesting compilation of texts, that show a variety of themes even if there are certain through-lines such as disease, and a focus on some particular texts more than others. Demons in Late Antiquity is presented as an oversized 6.8 x 9.6 inch hardback in a fetching shade of red. Illustrations are limited to Christoph Markschies’ essay with slightly muddy photographs of some of the manuscripts he references, and the text is presented in the De Gruyter house style, with the body set in a mild slab serif that almost scans as a sans serif, giving a distinctly modern look that is ever-so-slightly unconducive to reading.

Published by De Gruyter